Step-up buyers searching the used big-cabin retrac single market rightfully consider the Piper Saratoga and Lance. These PA-32R models get thumbs up from passengers for easy ingress and egress thanks to a rear cabin door. Newer pilots like them because they’re an easy transition from plain-vanilla Cherokees. In the shop, the PA-32R is a familiar airframe with decent support, though these are complex high-performance airplanes and turbocharging on some models adds to complexity and upkeep.

Still, a well-cared-for Saratoga or Lance (especially one with speed mods, new avionics and spiffy paint and interior upgrades) makes for a good ownership experience with high dispatch reliability. As we’d expect, prices have risen sharply since we looked at the market a few years ago. Here’s an update.

Engines, wings, tails

The PA-32R airframe was born in the mid-1970s when Piper lost the tooling for its retrac Comanche piston single in a flood. You don’t have to eyeball a Lance or Saratoga for long to see that the airplane has a lot in common with the fixed-gear PA-32 Cherokee Six. The retrac version was even easier to pull off because the PA-32 was already available with the 300-HP Lycoming IO-540, so essentially the only change was to fit retractable landing gear, though that meant a new engine mount and changes to the wing. Piper also modified the wing spar in the process, allowing a 200-pound boost in gross weight, to 3600.

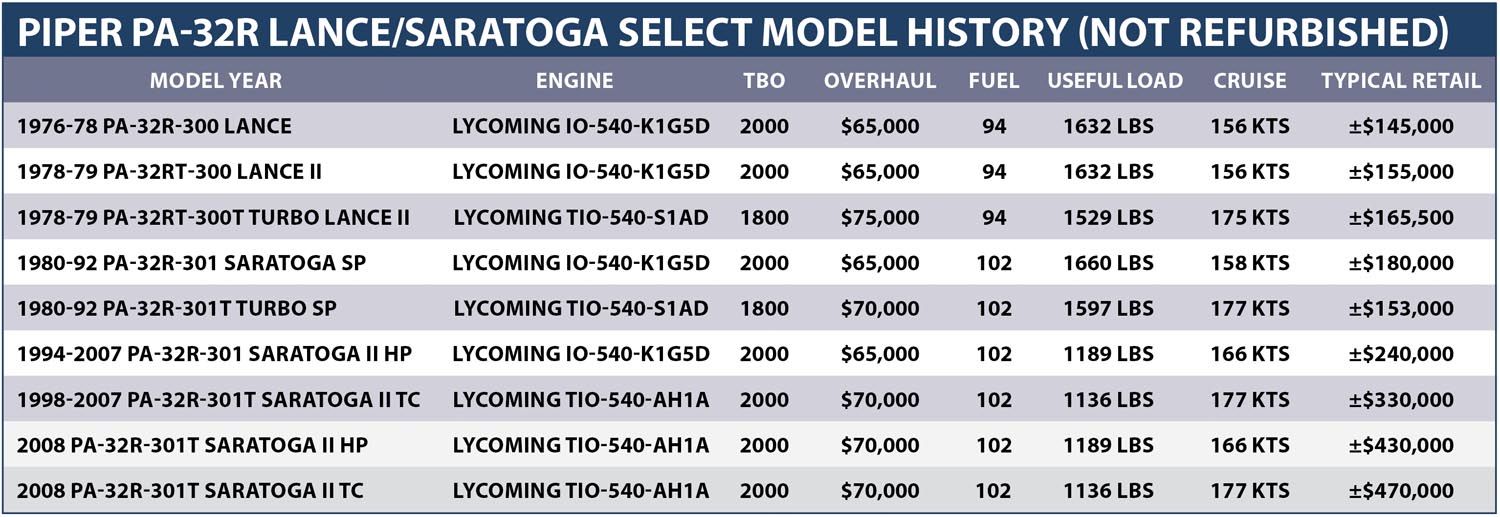

As for engines, there was a Lycoming IO-540-K1G5D with a 2000-hour TBO in the normally aspirated Lance and the TIO-540-S1AD with a TBO of 1800 hours in the turbocharged model. The D nomenclature means that the engine has the infamous Bendix dual magneto system. For going places, fuel capacity (and weight saving) is key and the Lance originally held 94 gallons in four tanks, later upped to 102 gallons in the -301 Saratoga models.

The Lance remained essentially unchanged for two years until Piper decided that T-tails were a good match for the turbo models. These are Lance II (PA-32RT-300) and Turbo Lance II (-300T) model designations. But word spread that when the stabilator was moved up out of the propwash, the airplane’s handling suffered. In particular, takeoff runs increased significantly since it took a good deal of speed for the stabilator to become effective, and when it did, the result was a pronounced pitch-up. Some complained of lack of rudder authority. In 1980, two years after the T-tail’s introduction, Piper reverted to the original tail design.

The Saratoga (PA-32R-301) came on around 1980 and sported a semi-tapered planform wing to replace the Piper signature Hershey bar. As before, there were turbo versions available, designated by a T at the end of the model number.

Turbos, speed, loading

The turbocharged models have AiResearch turbos with wastegates mechanically linked to the throttle controls. It’s pretty much old school because you have to adjust the throttle to maintain manifold pressure during climb, and it is possible to overboost the engine if too much throttle is applied. We always thought that the MP gauge is inconveniently located in front of the pilot’s right knee (big-screen engine displays solve that wart), but there is an overboost warning light on the panel’s eyebrow.

You’ll spot a turbo Lance II by its unusual “fish-mouth” oval scoop in the nose bowl. This updraft engine-cooling system takes air in through the scoop and forces it up over the cylinders, then back down and out through the cowl flaps. Turbo Saratogas have more effective cooling systems, replacing cowl flaps with louvers mounted on top and on the bottom of the cowling, plus a popular mod is to add an intercooler.

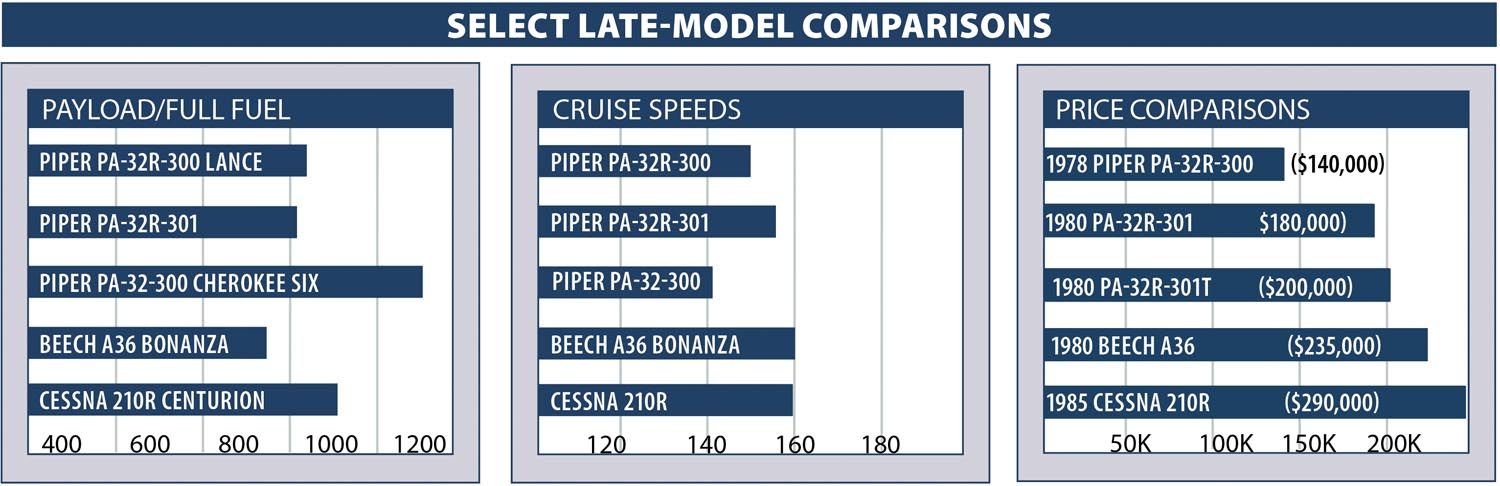

Don’t expect any normally aspirated PA-32R to outrun most modern-day speedsters, or barely keep up with same-vintage Bonanzas, Mooneys and Cessna Centurions, to name a few. However, we’ve seen well-modded Lance models get close. At 75 percent power, a Lance cruises at 158 knots while burning 18 GPH. The Saratoga SP isn’t faster, but improvements in induction air cooling allow their engines to be leaned to peak EGT, saving a couple of gallons an hour. The turbocharged airplanes can cruise at 177 knots while burning nearly 20 GPH up high, but at lower altitudes they’re only a couple of knots faster on the same fuel.

Ground rolls for the Lance and SP are posted as 1380 and 1200 feet, respectively. Initial rate of climb is just over 1000 FPM—not blazing compared to something like a Cirrus, but not terrible, either. But what these airplanes lack in speed they make up for in utility.

The cabin is over 10 feet long and 3.5 feet high. Shoulder room for the front and center seats is 4 feet and 3.5 feet for the back row. Most 32Rs have club seating and there’s a big side door for the passengers. Many owners might pull a rear seat or two for extra storage space.

As for cockpit ergos, step-up pilots notice the fuel selector is a bit different from the familiar PA-28 sidewall-mounted pointer, being sensibly located on the center pedestal. One thing we don’t like is the sump-draining procedure, which isn’t a simple matter of sticking a fuel tester in a quick drain. Put a bucket under a nozzle in the belly, then get back in and hold down a lever located under the right center-row seat while simultaneously switching tanks.

Later PA-32Rs have some good crashworthiness features, including seats with S-shaped frames designed to progressively crush on impact, plus a thickly padded glareshield. Interior upgrades make for an even better cabin experience. And when it comes to hauling people and their stuff, four good-sized adults with lots of baggage and full fuel is easily possible. The turbo models are a bit more limited. Owners tell us that realistically, with six people aboard, a PA-32R can carry enough fuel to fly 2.5 to 3.5 hours.

The CG range is quite wide, but with only two people aboard, care must be taken to avoid exceeding the forward limit. There are two baggage compartments, both with a 100-pound capacity: the nose bay and a large one aft of the rear. Owners of T-tail models learn to put 50 pounds in the aft baggage compartment to bring the CG aft into the center of the range.

Wrenching them

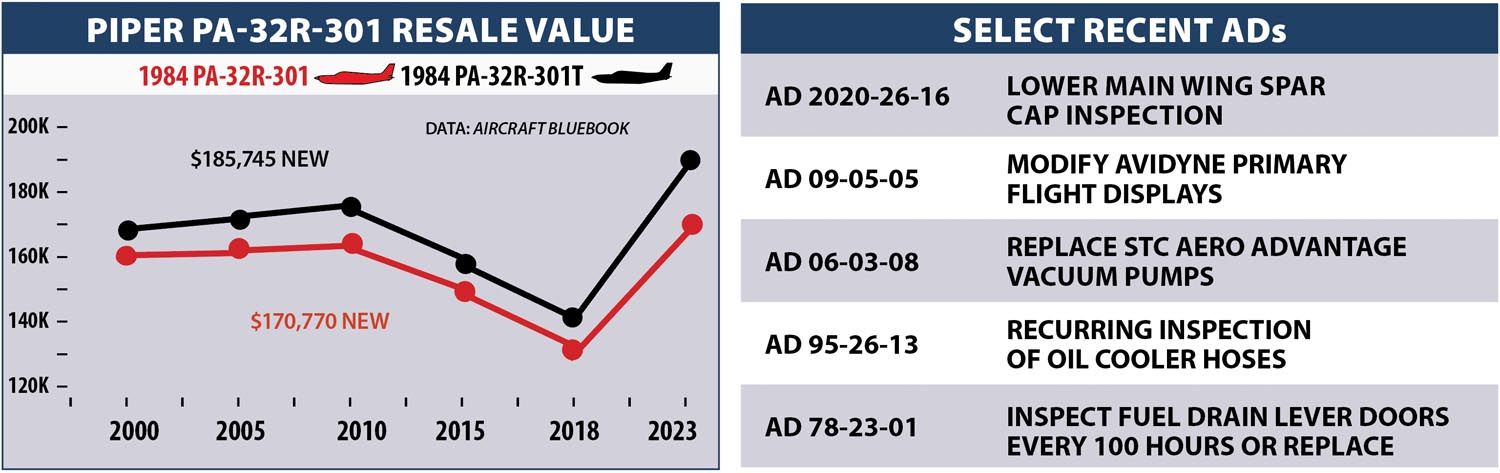

Maintenance won’t be as simple (or cheap) as a simple Cherokee. For starters, do a careful prepurchase evaluation by a shop that knows the steed, and have it look carefully at all applicable ADs. A rash of engine fires in turbocharged Lances and Saratogas prompted an FAA airworthiness directive requiring portions of their exhaust systems to be periodically inspected and eventually replaced. The AD targets the fittings on a 90-degree elbow between exhaust ports and turbocharger in the Lycoming TIO-540-S1AD engine powering the big Piper singles.

AD 2020-26-16 recently made the spotlight for the potential of wing separation caused by fatigue cracking in a visually inaccessible area of the lower main wing spar cap. This AD requires calculating the factored service hours for each main wing spar to determine when an inspection is required, inspecting the lower main wing spar bolt holes for cracks and replacing any cracked main wing spar.

Like all retracs, plan on good upkeep of the landing gear components. Broken nosegear actuators and cracked or broken nosegear trunnions aren’t out of the question. Still, owners like the free-falling gear in case of electrical system failure. Other items we hear about include cracked engine mounts, exhaust system leaks and separations, broken magnetos and loose stabilator attachments. Keep it well-maintained. There’s plenty of resources to boost your maintenance and modification knowledge, including the active PA-32 Six Saratoga and Lance Owners and Pilots Facebook group. There’s also the Cherokee Pilots Association at www.piperowner.org.

Market and insurance

Market and insurance

Before making a deal on any PA-32R, get an insurance quote. The airplane’s retrac status could be a deal breaker for some in the current hard insurance market. As expected, prices are way up on these airplanes. As one example, Aircraft Bluebook suggests that a 1976 Lance has an average retail price of $145,000—up from $92,000 just a few years ago. Turbo models might sell for a $20,000 premium. Later-model Saratogas easily flirt with $500,000 and ones with high-priced avionics upgrades and newer engines fetch even more.

No matter the vintage, owners simply like their airplanes because they work we’ll for traveling in comfort. “As a 6-foot-6-inch former NBA player (with a 6-foot-tall wife), the size of the Lance’s cabin is the biggest selling point for us,” Ben Tankard told us. “Our useful load is 1334 pounds, fuel burn is just under 15 GPH (ROP) and we plan on 160 knots in still-air sweet-spot altitudes,” Paul Weintraub said about his well-kept 1981 normally aspirated Saratoga. “Great step-up plane for pilots wanting more room for a growing family,” David Engle said of his Lance. He’s paid between $4000 and $7000 for insurance, with a $225,000 hull value.

Last, it’s easy to make these airplanes go a bit faster with gap seals, fairings and speed cowlings, which are available from a number of companies, including Knots 2U (www.knots2u.net), Laminar Flow Systems (www.laminarflowsystems.com) and LoPresti (www.flywat.com), to name a few. There are also a variety of propellers. If support is high on the must-have list, the PA-32R is worth a look.

We were also impressed by the small number of runway loss of control accidents (three, two of which were on takeoff), hard/bounced landing mishaps (four) and times the landing gear refused to extend (one). The aircraft has good low-speed handling and manners on the ground as we’ll as a well-designed gear system. In addition, only three pilots forgot to extend the gear, a tribute, we think, to an automatic gear-extension system being active on the marque for many years.

The low number of fuel-related accidents (six) is, in our opinion, a tribute to a well-designed and positioned fuel selector. Of those accidents, two did involve pilots who mispositioned that selector, one who didn’t remove some three quarts of water from the left tank and three who ran the tanks dry.

While only one pilot lost control after touchdown on landing, four landed hard enough to damage the airframe and five discovered that the airplanes will float a long ways if extra speed is carried on final—they went off the end of the runway. We were intrigued that one pilot managed to do so on a 5000-foot-long runway.

Fifteen of the 84 mishaps were due to engine power loss, usually because of lack of maintenance or maintenance errors. One stoppage occurred on the first flight after maintenance where the pilot elected to forgo a test flight over the airport and launched on a cross-country with a passenger. It got quiet just outside of gliding distance home because the fuel injector line to the number-six cylinder had not been properly attached.

Things got less impressive when we looked at takeoff and climb accidents. Putting it bluntly, the PA-32R series airplanes are poor short-field machines, especially when the density altitude begins to climb. Operating near, or above, gross weight makes those days even more challenging.

One pilot, launching just above gross weight, rotated, but the airplane did not lift off. Persisting, he raised the nose farther—eventually smacking the tail on the runway. He then lowered the nose so aggressively that the nosegear collapsed. Six pilots realized that they were not going to get off the ground in the remaining runway, aborted their takeoffs and went off the end.

Seven pilots got their heavily loaded airplanes into the air, or made a go-around, on a hot and high day but stalled trying to climb out. Two climbed out of ground effect but were unable to go any higher and put the airplanes down on rising terrain, one after the engine monitor showed he had repeatedly tried to adjust the mixture to get more power.

We were troubled to see how many pilots crashed attempting to fly VFR in IMC and either lost control or hit something—15, a startlingly high number. Two were Alaska Part 135 operators scud-running with revenue passengers. Three pilots took off over water on dark nights and fell victim to spatial disorientation and spiraled in. Three pilots on IFR flights lost control in IMC.

One pilot regularly flew into an unlit airport at night using his GPS and circling until he spotted the runway. That was until there was a low ceiling. He circled at varying altitudes for 54 minutes before hitting a tree at the approach end of the runway—while tracking 90 degrees to the runway heading.