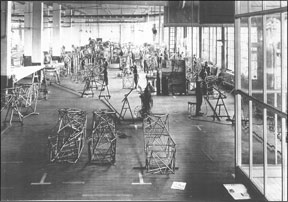

In the peak of Pipers Lock Haven, Pennsylvania, glory days, William T. Piper was rightly seen as a visionary. But no one could have imagined how enduring that vision would be, to the extent that 70 years later, several companies are building brand new Cubs that clearly trade on the mystique of the old yellow classic. Look www.j3-cub.com elsewhere in this issue for our review of two LSA Cubs to see what we mean. The only reason that “Piper Cub” is no longer the standard generic name for every little airplane flying is that the generation that made it so has been displaced by younger folks to whom flying holds little attraction, much less romance. The reality is that Cubs are a rarity at most airports. And if they are there, theyre likely hangared and kept pristine by owners who consider their J-3 a flying pride and joy. While the 1931 Aeronca C-3 was the first of the relatively inexpensive general aviation airplanes to be a big seller, by taking early advantage of the creation of the small horizontally opposed engine, Aeronca failed to make improvements to it. So, in the late 1930s, when FDRs Civilian Pilot Training program created a big demand for inexpensive trainers, it was the more advanced Piper Cub that became a mega-seller and brought general aviation to the masses, even if Piper did copy the C-3s paint scheme. Cubs have an almost cult-like following as each year new pilots brought up on the mundane handling of nosewheel trainers discover the pure fun of stick-and-rudder flying in a ragwing airplane. The first airplane to carry the Cub name wasnt a Piper at all but a Taylor E-2 model, powered by a Salmson radial engine. It first flew in the early 1930s with moderate success in the market. The J-3 didnt appear until 1937, after William Piper had bought out Taylor, and it was an offshoot of the Taylor design. By modern standards, the first J-3 would have been classified as sport aircraft, which, it in fact is today. The 1937 J-3 was powered by a 40-HP Continental A-40 and had a 9-gallon fuel capacity. The following year, Piper offered a 50-HP Continental as an option and a year later, in 1939, a steerable tailwheel and a 12-gallon fuel tank became standard. At that point, the 50-HP Franklin engine appeared as an option, in addition to an engine of similar horsepower made by Lycoming, whose plant was eventually just down the road in Williamsport, Pennsylvania. More than 1300 J-3s were sold in 1939, as the CPT spurred demand and the Depression eased. Nineteen-forty saw the evolution of the J-3 into the classic form in which most models survive today, with a 65-Continental up front or, in fewer cases, the Lycoming or Franklin variants. Most had wood props, although over time, most of those have been converted to metal props. Piper continued to pour Cubs out of its factory until the December 7, 1941, Pearl Harbor attack sent the J-3 into uniform. During the war, Piper built some 5000 L-4 versions of the J-3, slightly modified with olive drab paint jobs, electrical systems and heaters, providing the barest of creature comforts for an airplane known for its Spartan appointments. A Piper publication from the early days of World War II trumpeted the L-4s patriotic versatility: “There is no reason why Piper L-4s couldnt set down American Commandos behind enemy lines. And, when the boys completed their missions of destruction, these planes could get them back with speed and comparative safety.” Piper was ready when the war ended in 1945 and transitioned quickly into building airplanes for thousands of returning vets. The following year, an astounding 6320 Cubs were built, with production reaching 50 a day at one point, or one every 10 minutes. The market collapsed in 1947 and production plummeted to 720 Cubs-respectable by modern standards but a shock after the previous year. By the end of its production run, 14,125 J-3s had been built. Less than half that many remain flying in the U.S. Looking at what J-3s sold for when new, some of those old military jocks probably slap their foreheads in regret for not picking up a couple of dozen. In its heyday, the Cub sold new for $1595; or $17,268 in early 2007 dollars. It cost about what the typical car did. By the 1970s, Cubs were quite a bargain, averaging about $2500 or so. Prices shot up through the 1980s and 1990s, until they began to settle down about five years ago as the prices of other general aviation airplanes stagnated or began to slip and kit-built Cubs began to appear. A newly restored showpiece with a zero-time engine and original equipment and instruments can bring $35,000 or more. Even a barely flyable hangar queen will bring a nice piece of change as Cubs have a certain cachet not shared by most of its contemporaries, probably due to the ability to fly with its clamshell doors open-for many, an ideal compromise between open cockpit and closed cabin. A cold-eyed examination of the value of a Cub, based on comparative performance, indicates its not an especially good deal. Consider that a Taylorcraft of a much newer vintage-say mid-1970s-sells for $10,000 less and an Aeronca Champion (circa late 1940s) which has slightly better performance, for $4000 to $5000 less. The reality is that no one buys a Cub for what it can do but what it is: a classic with an appeal the others lack. “Only the Cub can attract the really top dollar,” one rebuilder told us. Simply put, the Cub aura transcends its objective characteristics. Does that mean that its a good investment airplane? In terms of appreciation in real dollars, no. However, historically it has held its value much better than its contemporaries and, so long as the buyer doesnt have to undertake a restoration, a Cub should be the best of the 1940s tube and fabric airplanes in terms of bringing the most when its time to sell. Although the 65-HP Continental was the standard Cub engine, many have been refurbished with progressively more powerful engines. There’s little difference between the 65- and 75-HP models, but the progressively bigger engines provide extra climb rate, especially for high-attitude or float operations, where the Cub is a marginal performer. The larger engines may raise a Cubs value by $500 to $1000. But the 65-HP engine is perfectly adequate for most Cub flying and is preferred for ultra-original restorations in which any variation from original configuration is considered a drawback. The Lycoming and Franklin 65s are somewhat rare these days and carry a price penalty of $2000. The Lycoming actually puts out something like 50 to 55 HP (with less fuel consumption), while the Franklin suffers from a parts scarcity. Speed is relative, of course, and the Cub isn’t relatively slow. Its very slow. Typical cruise speed is about 70 MPH with the 65-HP and 75-HP engines, while those sporting the 85-horse mills can streak along at 80 MPH. Then again, Cubs arent cross -country airplanes. With only 12 gallons aboard, practical unrefueled range is about 150 miles, after which you’ll want to get out for a stretch anyway. An

Cub History

Prices

Power Plants

Performance

The Cub comes into its own not in long-distance cruising but in operations off airports with grass runways. At light weights, on cool days, the Cub is an excellent short-field ship, particularly with the 85- and 90-HP engines. The fat wing delivers stall speeds somewhere around 40 MPH. Heavy or hot, it will still lift off in a short distance, but climbs over nearby obstacles can be unpleasantly sporty, given the airplanes high drag and lack of surplus thrust.

Stick and Rudder

The Cub has a reputation as a docile, easy-to-handle airplane that just about anyone can fly. Its considered a big teddy bear, ever forgiving of ham-fisted pilots. It isn’t.On the runway, the Cub can be a ditch lover and like any other taildragger, it will groundloop if given the chance, although its considered one of the better handling taildraggers. For pilots used to toe brakes, the Cubs heel brakes are weak and awkward.

The wing has no dihedral, meaning little roll stability. It has very sluggish ailerons that generate a lot of adverse yaw, thus requiring a good deal of rudder. Even a mild turn will require a healthy stab at the rudder, something most pilots trained on

nosegear airplanes have to learn. The stall, if the controls are coordinated, is relatively docile; however, the horizontal stabilizer has no camber which helps generate a very rapid roll off and pitch down into an incipient spin at the stall if the ball is not absolutely centered.

That will eat up 300 or 400 feet in a hurry. This characteristic has killed a lot of Cub pilots and passengers who were maneuvering down low. So much so that it is called the “Moose Stall” in Alaska from the number of moose spotters who have gone to their reward after an uncoordinated stall in a turn a few hundred feet above the trees. Our review of fatal accidents over the last 10 years showed that about half involved low-altitude maneuvering into either a stall or impact with terrain.

With adequate altitude, the Cub is a first-rate spin trainer; it will stall and spin easily compared to later training aircraft such as the Cherokee 140. Conventional anti-spin control inputs will recover it easily.

The soft bungee cord suspension absorbs bounces we’ll and the big rudder gives excellent directional control. However, the Cub can be humbling to land, requiring deft footwork to maintain directional control, especially in all but the lightest crosswinds. The Cubs light wing loading makes it a kite in gusty conditions. With the low landing speed, a 15-knot crosswind can present a major challenge. New Cub owners are we’ll advised to seek competent instruction before soloing.

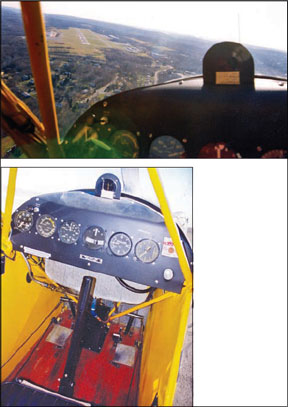

Cabin Comfort? No

Getting into the back seat-from whence you solo-is not so bad but ingressing the front requires some contortions. Once in the back, leg room is acceptable, with the legs extended forward to the rudder pedals and brakes. The front seater is balled up in a painfully cramped seating position thats not comfortable for any length of time.

Baggage room is essentially zip; there’s room for perhaps a loaf of bread in the

www.cub-club.com

canvas “luggage compartment” behind the rear seat. These days, most J-3 pilots mount a portable GPS somewhere in the cockpit, along with a handheld VHF radio for self-announcing on CTAFs. Beyond that, the instrument panel has the bare necessities. There’s a tach, an airspeed indicator, oil pressure gauge and altimeter. The fuel gauge consists of a cork float supporting a vertical a wire that is visible through the windshield. For such a small, simple airplane, a Cub has the potential to eat up lots of cash. Derek DeRuiter of Northwoods Aviation in Cadillac, Michigan, has, with his father rebuilt scores of Cubs over the years and offered some comments regarding things to check carefully on any airplane considered for purchase as an unintended restoration can eat your checkbook.

Fabric condition

: Cubs were originally covered with Grade A cotton, it should be avoided unless you are a fanatic for authenticity and willing to pay the price of regular recovering. It lasts maybe eight years if the airplane is hangared. Most Cubs are now covered with Dacron fabrics such as Ceconite. Properly applied and protected from ultraviolet radiation, these fabrics will last as long as youre likely to own the airplane.Engine condition

: TBO of the little Continentals is listed as 1800 hours, but the number is almost irrelevant, since most J-3s arent flown much and succumb to time and lack of use rather than hours. An engine may have only 600 hours since overhaul, but if the overhaul were in 1979, the engine may or may not be long for this world. Check compression and oil pressure.Rust:

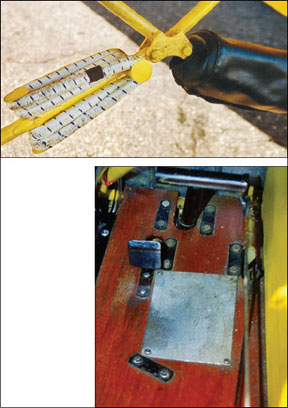

Check the lower rear longerons and the tail post. They do rust; don’t buy an airplane without carefully checking this area.Wing struts and strut forks:

Made of the same rust-prone steel as the fuselage tubes, these critical parts have a long history of corrosion problems. A series of ADs applies to this critical area requiring inspection every 100 hours until replacement; make sure that all have been complied with.Fuel tank and drain:

Original Cub fuel tanks were made of lead-coated steel, and they rust out regularly where water collects in the bottom. (Be especially wary of the 1940-45 J-3 and L-4 models, when the factory was skimping on the lead coating.) An AD also requires a new fuel drain. Many, if not most, of these tanks have been replaced by aluminum tanks but check the logs and inspect to be sure.Wooden wing spars in pre-1946 airplanes:

Check for dry rot and cracks.Landing gear attach fittings: A weak point, check between them for condition, especially if the airplane has been on floats. The landing gear bungees are good for about three years.

Misc:

The elevator trim system components wear out; inspect carefully. The rudder and elevator hinges wear out, also check carefully and look closely for corrosion.Accident Damage:

Cubs are subject to all sorts of minor landing and takeoff accidents and their huge wings and light weight make them very prone to wind damage while tied down.

www.cub-club.com

We would suspect that the vast majority of Cubs have been damaged at some time or another and a fair number of those now flying were built from the wreckage of two or three or more and one data plate. Or from a data plate and parts from Univair. Thats OK, if the work was done correctly. Only a Cub expert will know, however, so we recommend contacting one of the Cub groups for a list of shops that know the airplane.

We wouldnt be put off by an airplane that has been groundlooped-most have-but make sure damage has been repaired correctly. Again, retain a Cub expert to have a look. It doesnt take long to do a thorough, professional prebuy on a Cub.

Parts, Support

Although Piper has long since stopped making the Cub, finding parts and support to keep one flying is a snap, thanks to a couple of sport aircraft parts houses. In many cases, the replacement parts are vastly superior to the originals; aluminum fuel tanks, for example, are lighter and far less prone to corrosion than the originals-not to mention cheaper.

The two biggies in Cub parts are Univair and Wag-Aero, both of which stock a complete selection of PMAd Cub parts. Wag-Aero Group at P.O. Box 181, 1216 North Rd., Lyons, Wisconsin 53148, 800-558-6868 and www.wagaero.com. Contact Univair Aircraft Corp. at 2500 Himalaya Road, Aurora, CO 80011

888-433-5433 and www.univairparts.com.

An excellent owner group is the Cub Club, at 1002 Heather Lane, Hartford, Wisconsin, 53207, 262-966-7627, www.cub-club.com. In addition, there are a couple of excellent Web sites devoted to the Cub. One is www.j3-cub.com, which features photos, memorabilia and a wealth of Cub knowledge that means a would-be owner is never more than a click away from having questions answered.

Although its aimed more at Super Cubs, www.supercub.org also includes some information on J-3s. Its rich in photos and Cub lore.

Owner Comments:

Fuel burn, about 4 to 4-1/2 gallons per hour. The J3 flies like a kite, light feel, is very controllable, a delight to fly but not an airplane to travel in.

The cost for labor to do the annuals is nothing because of a deal with a mechanic/pilot who does the maintenance for the privilege of flying it. The cost of insurance is about $600 per year. My cost of purchase plus restoration, to date, is about $30,000.

The J-3 is a Big Boy Toy that doesn’t depreciate. You can fly it, have a lot of fun and get your money back.

Dale R. Dolby

Ive owned my 1946 J-3 for six or seven years, after I had been flying about 15 years. I had been using my Turbo Saratoga with all the bells and whistles mainly for serious traveling over medium to long distances and I continue to do so, but I was looking for something to get me back to the roots of flying.

The only problems my Cub has given me are those to be expected with age. It doesnt leak any more than a 60-year old human. Repairs and annuals are easy and Ive done most of them myself with a sign-off. The most recent annual cost me about $150 for parts, four quarts of oil and $200 for the sign-off inspection. Compare that with the annuals on my PA-32, which run from $5000 to as high as $15,000 in a bad year.

Even though my J-3 is hangared all the time, this year I had to re-dope a few spots and open the empennage to take care of some corrosion. Last year I had to replace the roof window. For these reasons I would not recommend keeping a J-3 outside.

I fly the Cub strictly on good weather days with low winds when I have no particular place to go. Its also very good as a photography platform. It gets me back to what real flying is all about. Wherever I land, the Cub turns heads and attracts gawkers. It certainly is not a showpiece, but there just arent that many of them flying.

I paid about $23,000 for my J-3 in 2000. Although I don’t consider it an investment in other than my own good times, it has appreciated in value. I have simple fun with it, the cost of upkeep is incredibly low compared with everything else in aviation and its a piece of history. Im glad I have it and would recommend a Cub to anyone looking for the kinds of experiences unique to simple airplanes.

Brian Peck, MD

Middlebury, Connecticut