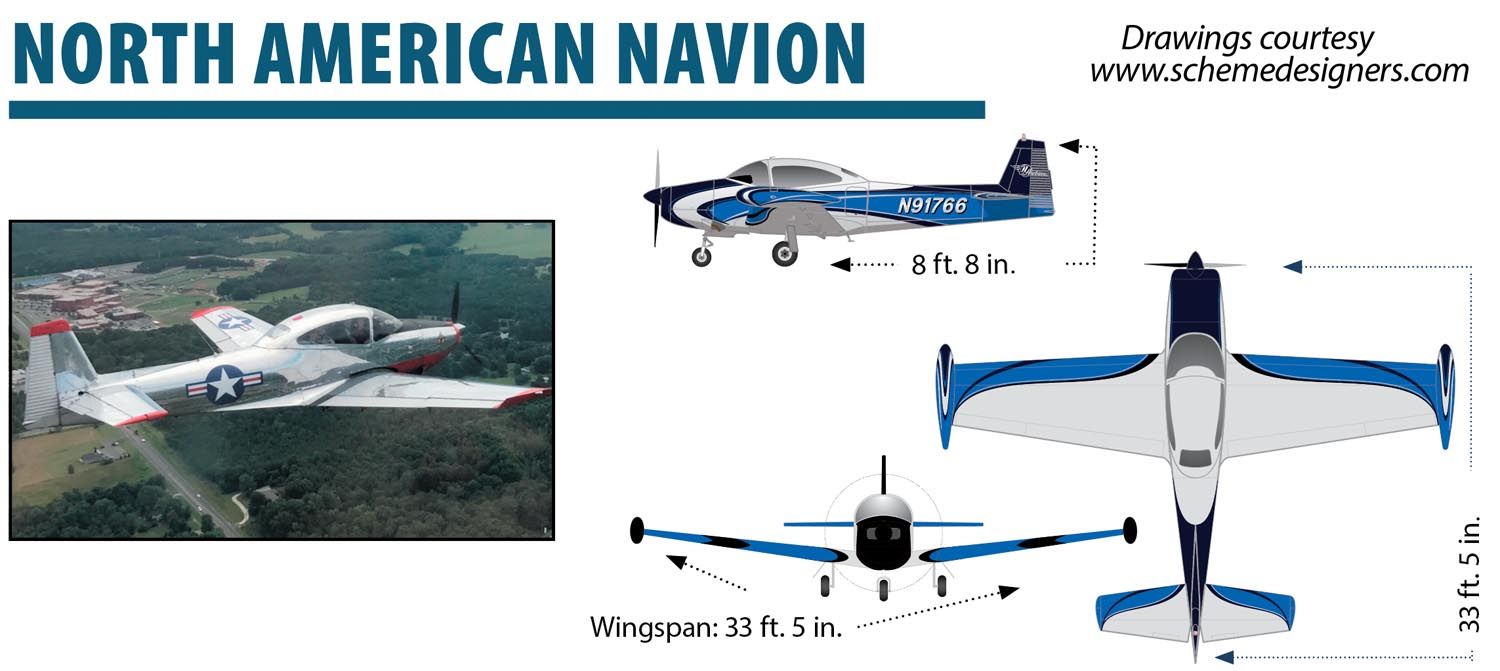

With retractable landing gear, a slide-back canopy and a familiar fighter wing, you won’t have to eyeball an early Navion for long to see that it was intended for military duty. But rugged cool-factor is but one reason why Navion owners love these sporty singles, made even better with quality support from the American Navion Society.

Support is a good thing—these are old machines, some dating back to the mid-1940s. Barn find? Be prepared to give it some love and spend plenty of money to get it up to snuff. Ones that have been nicely upgraded and given the care they deserve will sell for hefty premiums, and Navions in general have increased sharply in price since we last looked at the market four years ago. Before making a deal on any model, do a thorough prebuy evaluation and get an insurance quote.

Military grade

Flash back over 80 years ago when North American hoped to sell thousands of Navions to the military, but fell quite short. At just shy of 3000 total production, the airplane lasted all the way to 1976, having been manufactured by different companies in various models and incarnations. Still, the airplane thankfully retained a sturdy build quality with classic fighter-like looks.

You’ll find a variety of engines under the cowlings of these airplanes. The first Navions were powered by a 185-HP (205-HP for takeoff) Continental E-185.

After building around 1100 Navions, in 1948 North American sold the aiplane’s rights to Ryan of San Diego—the same Ryan that built the Spirit of St. Louis for Charles Lindbergh. Ryan dubbed its Navion the A model and built another 1200 before ceasing production three years later. Some of the later Ryan models had a 225-HP Continental E-225. The last B model, which used a 260-HP geared Lycoming GO-435 engine, was the last model of the original genuine Navion. The airplane remained out of production until 1955, when the rights were sold to Tubular Steel Corporation (TUSCO), which specialized in rebuilding and updating old Navions with Continental IO-470 engines of 240, 250 and 260 HP. These are known as the D, E and F models, respectively. TUSCO resumed production in 1958 and introduced some refinements. The sliding canopy was replaced with a door, fuel capacity was greatly increased and a 260-HP Continental was added. Thus was born the so-called Rangemaster G model, but production was short-lived. About 50 were built before hurricane Carla wiped out the factory in 1961.

Supporting the stables

A huge resource with Navion ownership comes from the American Navion Society. Find them at www.navionsociety.org. Some of its members bought the Navion rights and in 1967, they began building a handful of Rangemaster H models, which had a 285-HP Continental IO-520 engine. But that company folded, too. Twice in the mid-1970s there were attempts to revive the Rangemaster. Only a half-dozen or so airplanes were built.

Today, the type certificate and manufacturing jigs are owned by Sierra Hotel Aero, which provides service and parts.

Navion guru and American Navion Society president Rusty Herrington makes a good point in that no two Navions are quite alike. There are many engine configurations, from the original E-185 Continental through the big bore top-induction Continental engines with over 300 HP. The 285-HP IO-520-B series engine is very common and a very good installation, he told us.

Performance, gotchas

Early 205-HP Navions cruise at about 135 MPH on 11 GPH. The 225-HP versions add about 5 MPH to that number in exchange for a gallon more of fuel burn.

You’ll go about 170 MPH or so in the 240-, 250- and 260-HP second-generation D, E and F Navions. In contrast, the 1951 B model, with the geared 260-HP Lycoming, ranks as the most inefficient Navion built: It can manage only about 153 MPH on 13.1 GPH. Other lower-priced used retractables such as the Comanche 180 and early Mooneys fly faster and use less fuel, but they’re also more expensive and lack the Navion’s larger (yet stark) cabin environment. “I live in Florida and, though I am at sea level, I often see density altitude of 1500 to 2000 feet. I can climb out at 1000 to 1250 FPM. With full wing tanks and close to 1000 pounds of people, I’ve easily climbed out at 750 FPM,” Ken Hewes said of his Continental E-225 powered 1947 Navion.

Fuel capacity differs widely from one Navion to another, so it takes effort to pin down actual payload numbers. Although the basic fuel system has 40 gallons, many Navions have an extra 20-gallon tank under the rear seat or in the baggage compartment. Also, there are several different types of tip tanks available, which some owners say can yield a range of 1000 miles.

Late-model Rangemasters had fuel capacities of up to 108 gallons, although that much fuel would limit payload. Generally, expect still-air range of about 600 miles in an older Navion with 60-gallon tanks. This will be reduced somewhat as extra passengers and baggage are added.

Despite its beefy construction, the Navion weighs 1900 to 2000 pounds empty with a gross weight of either 2750 or 2850 pounds, giving it a useful load of around 800 pounds.

With four people and 100 pounds of baggage, there isn’t a lot of room for fuel. The 260-HP version has a useful load just a little better than the A model’s. Unfortunately, it burns 20 percent more fuel, so on the same trip, the load would be more limited.

The Navion was built a lot like the P-51 where the two wings were bolted together and then bolted to the fuselage. The wings house aluminum fuel tanks, coupled by rubber hoses. And of course those hoses get dry and ultimately crack. We’re told the only real way to get the tanks out is by pulling the wings off the airplane and separating the wings from each other. It’s a job, and Navion pros suggest finding an airplane that’s had this so-called wing de-mate in the last 25 or so years.

After working on our share of Navions, we agree with those who warn that almost every Navion has been on its belly at one point or another, but a gear-up landing typically doesn’t always do substantial damage other than taking out the flaps and the prop. And of course as with many old airplanes, paperwork might be light and missing some maintenance entries. Check the weight and balance and get it weighed when in doubt of the numbers.

Look at the landing gear during prepurchase evals. These are hydraulic systems, with the usual headaches with retrac links, hoses and pumps. Some older airplanes may still have the original single-piston hydraulic pumps, which should be replaced with new versions. Check for loose trunnions in the gear pivots and for play in the nosegear, causing shimmy.

And, since the Navion is a retrac, get an insurance quote before making a deal on one—especially if you’ve done lots of upgrades that increases the hull value. Owners like 71-year-old Leo Langston feel the sting.

“My rates basically went up for the hull coverage I had last year. After investing in a complete panel upgrade and autopilot installation, I had raised my hull coverage from $55,000 to $95,000 and I still had the $1 million liability coverage. That premium was just over $3750. This year no underwriter would even give me a quote for the $95,000 hull, though I could get $85,000 for a premium north of $4000,” he told us. He finally settled for a $75,000 hull valuel and the $1 million liability coverage for that same $3750 premium. “Either the insurers are depreciating my plane for me or since I am 71 now, the age factor is creeping into my rates and coverage,” he told us. Langston insures through the Texas-based Falcon Insurance Agency. If you’re happy with your coverage, we suggest sticking with the company for the long term.

Custom Navions

Like many old airplanes, annual inspections can either be easy or labor intensive, and we think having a shop with extensive Navion experience is the absolute best way to maintain one. We’re told that typical annuals could run $4000, while others might be less or a lot more. Before doing any mods, get the airplane up to date on maintenance and repairs.

Navion Customs in California (www.navioncustoms.com) owns the STC for the big 300-HP IO-550B and is working on an STC (some have been installed with a field approval) for the 310-HP top-inducted Continental IO-55OR, an engine that’s done we’ll on the Cirrus SR22. It requires a cowling change to a two-piece cowling and you’ll likely have to change the mount. The prop being used in the STC is a three-blade composite MT propeller. Another respected source for mods, refurbishment work, avionics upgrades and anything related to Navion support is type certificate holder Sierra Hotel Aero (www.navion.com) located in St. Paul, Minnesota.

J.L. Osborne (www.jlosborne.com), which is part of GAMI, has the 20-gallon wing tip tank mod for the Navion. The tank is all aluminum and has recessed LED strobe and nav lights, a flush filler neck and a concealed drain. The tanks can improve lift, increase gross weight (250 pounds) and some report a few knots’ increase in cruise speed. Osborne suggests that typical installations could take around 25 hours.

As Ryan Douthitt at Navion Customs put it, “You really have a blank canvas because there’s so much that you can do to these airplanes.”

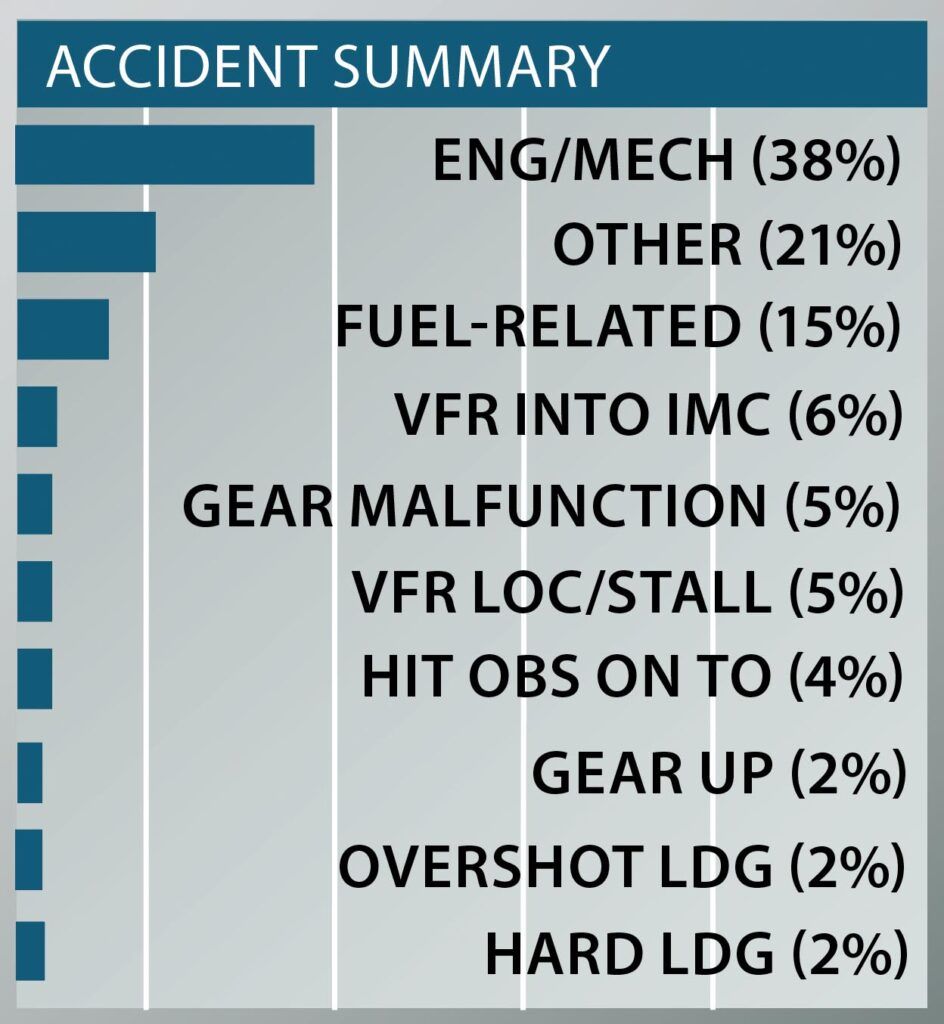

Navions are roomy, comfortable cruisers that slide through turbulence with a smoothness nearly unmatched and have handling that draws raves. Our review of the 100 most recent Navion accidents confirmed our opinion regarding handling, partially because we saw a stunningly low number of landing-related accidents: There were only two runway loss of control (RLOC) events, two hard landings, and two overshot landings.

There were also only five VFR LOC/stall accidents, most on takeoff in hot and high conditions with a heavy load and short runway.

There were also only five VFR LOC/stall accidents, most on takeoff in hot and high conditions with a heavy load and short runway.

Of course the good news couldn’t last; the number of engine stoppages—38—was among the highest we’ve seen. The majority were due to maintenance that simply wasn’t performed or was performed improperly. We were especially concerned that at least 15 of the accidents were due to problems with fuel system components that were worn out, loose or had been installed wrong.

Leaking and/or worn-out fuel selectors and gascolators led the hit parade for mechanical issues in engine stoppages. We think that one fire in flight was due to lack of fuel system maintenance. These are old airplanes with complex fuel systems that need to be maintained assertively.

If you’re buying a Navion, make sure the prebuy includes a careful look at fuel system components.

About half of the engine stoppage events were listed as cause unknown because the engines ran fine in the post-accident investigation. We have two hypotheses regarding a number of those stoppages. First, we think that carburetor ice may have been the culprit in at least five of the events—atmospheric conditions were ripe for it. We think that at least 10 stoppages that occurred immediately after takeoff may have been due to the pilot selecting the wrong fuel tank (often a tip tank) for takeoff.

Navions have fuel systems that aren’t necessarily intuitive and aftermarket mods can make appropriately managing them even more challenging. During our review, we learned that an attempt to take off using a tank that is placarded for level flight only often allows the pilot to get the airplane into the air. Shortly after the gear hits the wells, things become silent. Our take on it is to make sure you know the fuel system on the particular Navion you’re flying cold and have a plan for what tank you’ll use and when.

The unexplained engine stoppages were in addition to the 15 purely fuel-related stoppages, most of which were because pilots ran a tank dry and couldn’t select a tank that had fuel in it and get the engine started. Six of the accidents were due to simply running out of fuel and two due to fuel contamination.

Only two pilots forgot the gear on landing, but mechanical/maintenance issues caused five mishaps where at least one gear leg wouldn’t extend or collapsed on landing.

We felt for the Navion pilot who dove hard to avoid a flock of birds on base leg and wound up going under power lines and slicing off the vertical tail. He got it on the runway just fine, but as the airplane slowed, he couldn’t keep it from turning left into the weeds.

Owner Feedback

I’ve owned Navion N4833K since 1999. It was born in 1949 and is aging better than me. As is typical of these airplanes, it’s a family member. It has a combination of characteristics that are great. It looks big and imposing, but is actually easy to fly—so stable you can take naps on an ILS approach. It’s a comfortable traveling machine that’s not a speed demon.

My bird has the IO-470 and a three-blade McCauley prop. I file IFR for 150 knots (true) at around 8000 feet, with a power setting og 22 inches MAP, 2350 RPM and mixture lean of peak, which translates to 10.6 GPH and cool CHTs. It’s a great short-field performer. I flew it off of a 2200-foot grass field for 20 years—the big 8.5 tires take the bumps out.

Let’s talk maintenance. These are old airplanes with complex systems. I’m an A&P/IA and that helps, but the owner/operator will need to get to know the airplane at a molecular level and be willing to tinker. It’s not a rental 182. Membership in the American Navion Society is a must. I’ve never had a parts issue. The military bought a number of them, and as is typical with the military, there are enough parts to last for 200 years. Four years ago I bit the bullet and got a major upgrade: A new engine, propeller, Aspen glass, Garmin navigator, JPI 930 engine display and an S-TEC 55X autopilot. Now I don’t have to tinker as much.

In summary, these things are built like tanks. There is no spar in the wing and no spar carry-through. There’s no single point of failure so if you take a hit from enemy flak, you’ll be OK. All those years ago when I was considering buying one, I thought I’d call Wes at AVEMCO Insurance and see what he says (I’ve been with them since I bought a J3 Cub in 1976). He said, “Well, if you find one that’s been sitting out in a field for 40 years and been hit by a bulldozer, it’s probably OK”.

Every Navion is totally unique as there are many mods available. Over the years, I’ve occasionally considered trading for something else but, for the money, it’s hard to beat. Most importantly, my wife likes traveling in it. At this point, I’m planning on going to my grave with it.

Good hunting! Finding a family member is not easy.

A worthy read comes from the late, great Richard McSpadden’s AOPA prose “Today I sold the family Navion. It’s just an airplane”.

I’ve been a Navion (L-17B) owner for 23 years, rescuing an aircraft that sat unloved for decades before I started a “flying restoration” in 2000 and still fly it today.

As a long-term owner I can provide a pragmatic assessment of what it takes to own, fly and maintain these birds. I would say before diving in that these aircraft require “advanced ownership”—where the owner has to invest in learning to fly it correctly and expect to be hands-on in maintenance The Navion is not as simple as a Cessna 172, so it can’t realistically be dropped off for an annual inspection and picked up a few weeks later. Anyone that wants that hands-off approach to maintenance is better directed to another aircraft type. However, for an owner willing to commit, a Navion will return some of the best flying qualities available in a GA aircraft.

Navion prices vary wildly due to the ready availability of customizations for the airframe; from firewall-forward options to a non-structural instrument panel that can be very freely updated. It’s also often the case that aircraft have been maintained by mechanics unfamiliar with the type and the common issues and maintenance operations, especially the hydraulic system and on Continental E-series engines (E-185, E-225), plus the PS-5C carb and associated components.

A thorough, detailed pre-buy by an A&P very familiar with the type is absolutely required. Unfamiliar techs will miss things that are obvious to one with Navion experience. A Navion expert can also advise on a broad valuation and any issues that need to be addressed. Broadly speaking, E-Series-powered aircraft will sell for significantly less than any aircraft with a more modern firewall-forward engine install. Parts and expertise are becoming rare for the E Series, and a brutal prop AD in 2000 grounded many aircraft due to the cost of a replacement E-series prop being more than what a completely new firewall-forward would cost. Engines over 260 HP also require a “beef-up kit” that practically speaking require the wings to come off to install. And there are a number of known problem areas in the nosegear, trunnions and aft fuselage that need to be carefully validated as part of the purchase.

If the Navion has an Achilles Heel, it’s maintenance. Finding local expertise is required and can be difficult. Any A&P can learn to maintain one, but they must invest some time and effort for the type, especially the hydraulics and the E-series engine and prop. The Navion community is a bit crusty and cranky at times, but always supportive to people trying to maintain their aircraft. Many in the community generously give time freely as needed to educate pilots and mechanics.

Parts are an interesting challenge. On one hand, with only about one quarter of original production Navions flying (and over 60 airframes produced in parts for the U.S. Air Force), there are a lot of used and NOS parts out there. The challenge is the out-there part because components are spread across a number of large providers, Navion owners needs to be willing to take an active part in chasing down parts. There is little or no parts support from traditional vendors such as the otherwise well-stocked Aircraft Spruce, as one example, and owners need to get comfortable that with a 75-year-old aircraft, they’re going to learn about modern replacements and even owner-produced parts where there are no other options.

Like all North American designs, the Navion is a joy to fly. It’s perfectly harmonized in all axis of flight and extremely light on the controls. It’s commonly said you can fly the aircraft with two fingers, and that’s quite true. But it’s also extremely stable and really has no vices with no special skills to fly. Stalls are mild in all configurations but full dirty, usually just mush along versus breaking hard. However, with flaps and gear down, be ready for a hard stall and a wing drop. You don’t want to get slow on final. Short fields are easy and surprisingly short and it’s possible to get the bird off in 300 to 400 feet on the stock E Series engine, and landing quite short with good technique. The sight picture can be a bit odd on landing as the bird is tall. The stock E-series engine with the variable-pitch prop takes some operational training to fly effectively. It’s important to learn the fuel system—well—because of the number of customizations, some fuel systems are complex and usually all feed into a header tank with a return system that returns 10 GPH to the mains.

I’m whatever passes for historian on the military history aspect of the Navion, with a L-17 Facebook group (Preserving Navion Military Heritage and a website: www.L-17.org) on the L-17 sub-type. There’s more myth than truth out there, but the story is fairly clear at this point with the research I’ve done and published, and I’m happy to answer questions.

—Bill Lattimer, via email

Sierra Hotel Aero (www.sierrahotelaero.com and www.navion.com) has held the Navion type certificate for over 20 years and has all of the engineering drawings, tooling, equipment and the experience to provide parts and technical support for the Navion. Our goal is to support owners and maintenance providers around the world to keep the Navion fleet flying safely. Along with our in 5-axis CNC machining, fabrication, avionics and repair capabilities we also work with many specialized aviation vendors to provide modern replacement parts and upgrades.

Sierra Hotel Aero (www.sierrahotelaero.com and www.navion.com) has held the Navion type certificate for over 20 years and has all of the engineering drawings, tooling, equipment and the experience to provide parts and technical support for the Navion. Our goal is to support owners and maintenance providers around the world to keep the Navion fleet flying safely. Along with our in 5-axis CNC machining, fabrication, avionics and repair capabilities we also work with many specialized aviation vendors to provide modern replacement parts and upgrades.

We started in 1999 with an STC’d baggage door installation and recently completed a project that enables Navion owners to install modern avionics and a digital autopilot. As the surplus parts market continues to disappear SHA will be there to fill the need for OEM replacement parts for your Navion.

—Chris Gardner, Sierra Hotel Aero, Inc.

I’ve owned my 1948 Navion for 25 years, and did a complete ground-up restoration on it when I first bought it, including installing the beef-up kit and a Continental IO-520 engine. Over the years, I have upgraded the avionics and it has been a very reliable, comfortable, capable, fun airplane with a lot of panache. It is a good cross-country traveling plane, a good short-field plane, a great IFR platform, a true four-seats-and-full-main- fuel plane. It has wonderfully balanced, responsive and fun control harmony, it has plenty of room (even for big guys) and plenty of baggage space, plus we use quite a few of them for formation flying training, shows, and missing-man demos. I’ve flown the Navion in formation with everything from Chipmunks and Birddogs, to Nanchangs , Yaks, T-6, and even T-28s. A 1950 Navion promotional movie called “Yours to Fly“, which is available on YouTube, says “No other airplane does so many things, so well, and I think that states it nicely. The video is worth watching.

Originally designed and built by North American Aviation —builders of the P-51, B-25, T-6, F-86, X-15 and more—the Navion shows its heritage and is extremely overbuilt. Navions never have any in-flight structural issues, and the airframes do a very good job of protecting their occupants in a crash. When the Korean War broke out, the Army and newly minted USAF needed a rugged, capable liaison airplane, and the Navion was chosen, and went straight into service as the L-17. They served on rough, muddy fields, roads and even flew from the 558-foot-long decks of Escort Aircraft Carriers (CVEs), with no tailhooks and no catapult. They did forward air control, artillery spotting, general liaison duties, and served as flying staff cars for Generals, including MacArthur and Ridgway. Marilyn Monroe was flown around Korea in an L-17 Navion on her USO Tour.

The Navion / L-17 is about as close to a “practical” warbird as you can get. Navions allow you to participate in many aviation arenas—as a warbird, as an antique/classic, in airshows, formation flying, cross-country or just out for a $100 hamburger run with three of your friends.

The talent of the NAA engineers and mechanics really shows in the design of the Navion. Its slow-speed manners are impeccable, and the stall gives plenty of warning, but turns out to be a complete non-event. Navions have two different airfoils; a 15-percent thick NACA 4415 at the root and an undercambered NACA 6410 outboard, changing at the flap/aileron break. This, coupled with 3 degrees of washout, means that when the inboard section of the wing is stalled, and providing plenty of buffet via the 13-foot span tail, the outboard section is still happily flying and the ailerons are still in full control. There is no wingtip drop, and you can safely maneuver the plane with the ailerons we’ll into the stall. Navions are regarded as unspinnable. You can’t get them to spin with anything approaching a sane CG. This is one area of needed type-specific attention, however because about the time you notice that you are going 55 MPH, fully stalled, with the nose above the horizon and in complete control with the yoke, you may neglect to notice that you are descending at 2000 to 2500 FPM—with the nose in the air.

Speaking of CG, The Navion is very difficult to load out of CG and the CG barely moves in flight, unlike the Bonanza, for example. Unless you have baggage area auxiliary tanks, all of the fuel is carried in the heart of the CG envelope, so the CG does not move as you burn fuel. If you load too much weight in the back, the airplane will lift the nosewheel and sit on its tailskid. Get the tail back off the ground, and you’re fine. Much is written about all of the different max-weight limitations per a very convoluted type certificate data sheet and lots of mods. In practical terms, however the Navion will carry a lot more weight than you think, especially with the larger engines.

The Navion is a complex airplane, but not overly so. It was built for rough use in a simpler time, and while it behooves an owner to understand how the systems work, and certainly a maintainer needs to be familiar with the maintenance manual, nothing is all that tricky or difficult to understand. It’s all straight-forward. The fact that such a high percentage of them are still flying after 75 years is testament to that. One thing that is different than the average Beech /Cessna/Piper GA airplane is that the gear and flaps are actuated by a hydraulic system that’s similar to the T-6. There is an engine-driven hydraulic pump, and the system must be activated prior to moving the gear or flaps. In reality, the pump is always turning and you are just closing a bypass valve to pressurize the hydraulic system. I recommend leaving the hydraulics active all the time, except when in flight with the gear and flaps retracted. This provides additional security to the over-center gear downlocks when taxiing. There are no squat switches. If the engine-driven hydraulic pump fails, there is a manual pump. If that fails, or you lose all of the hydraulic fluid, there is an emergency extension handle that will pull the mechanical up-locks via a cable, allowing the gear to fall and lock by gravity. Again, NAA designers at their finest.

The Navion is one of the most highly modifiable airplanes out there. It is nearly impossible to find two Navions exactly alike after 75 years. We say “If you’ve seen one Navion you’ve seen one Navion!” So be sure to understand the different configurations of any one you may be flying. At a recent airshow, we had seven Navions lined up. No two of them even had the same engine!

These days, Navions tend to fall into two rough categories: Those that are closer to the original configuration, have basic instruments and smaller Continental E-series engines (185, 205 or 225 HP,) versus those that have been modified with larger engines, and often more advanced avionics. Continental O/IO-470, 520 and 550 engines of 240 to 260, 285, 300 to 310 HP. There are also a few “Super B” Navions that have geared Lycoming GO-435 or GO-480 engines of up to 295 HP. The smaller, lighter E-series-engine birds are delightful to fly, less expensive and use less gas. They are not as forgiving carrying heavy weights or at high density altitudes. They do not suffer as much of a speed deficit as one might think, being only 10 to 15 MPH slower on average than a 520-powered airplane. The E-series engines and their splined shaft propellers are becoming a challenge to support, however. One should have a good understanding of the issues before purchasing one. The geared Lycomings are good at takeoff, high altitude and at speed, but the additional complexity and expense of overhaul for the gearboxes, as we’ll as parts availability, are challenges that need to be clearly understood.

The big-bore Continentals make the Navion the airplane it should have been from day one. The engines and propellers are still in common use on Beech, Cessna and Piper airplanes and are we’ll supported, understood and reliable. A 285 or 300 HP Navion will give very pleasing performance; short take-offs, 1000-plus FPM climb, 155-165 MPH cruise and 1000 pounds or more of useful load. If you find a Navion with the IO-550R engine, it’s pure magic. These run faster while burning less fuel and run cooler than any of the others. A big-engine Navion will sell on average for around $100,000, depending on times, mods and avionics. That’s quite a bit less than a comparable Bonanza or Skylane and far less than a Cirrus. Small engine (E-series) Navions will go for about $50,000. The IO-550R Navions bring a premium and can run from $125,000 to $200,000 or more for really cherry examples.

The large 11.5 flaps that come down 42 degrees on any Navion allow for incredibly short and steep approaches, with over 20-degree glideslope angles possible without exceeding 80 MPH. This makes for very short landing roll outs and obstacle clearance on landing is not a problem. It is difficult to impossible to be too high on a landing approach in a Navion as deploying full flaps feels like stepping on the brakes.

With 20-gallon tip tanks, my Navion has easily accomplished non-stop flights of 750 to 800 miles (plus reserves) carrying two people and lots of baggage. Mine is not one of the faster big-engine Navions so I routinely plan 155 MPH for cross-country trips and will see 165 MPH on cool days if not too heavily loaded. In “race trim”, I’ve made 169 MPH. Some of the more modified Navions have exceeded 200 MPH in the annual Navion Society races, but that’s not a reasonable cross-country assumption. I plan 17 GPH ROP, or about 12 GPH LOP, depending on altitude. The main fuel tanks on all Navions hold 40 gallons, while big-engine Navions benefit from having auxiliary fuel for cross-country flights. There are tip tanks of 20 or 34 gallons per side, and/or baggage compartment or under-seat tanks of 20 gallons available. The landing gear speed is only 100 MPH, so you have a little slowing down to do before you can lower the gear. And once you do lower it, you should not exceed 100 MPH.

If you try flying with the original (1940s) fuel and hydraulic lines, you’re asking for a mess and potential problems. If your lines have been replaced within the last 20 years or so, with good quality hardware, they should be trouble-free.

One part that is becoming a little problematic to support is the main fuel tanks. They are hydro-formed, beaded aluminum suitcase-sized tanks that are contained within each wing root. If they start to develop leaks due to age, vibration or corrosion, some areas can be patched from outside the wing. Some can’t and require removing and splitting the wing to get the tank out. There are not a lot of NOS fuel tanks around, so they must be carefully repaired and restored. One should carefully look for signs of fuel leaks during a pre-buy inspection.

In order to operate and maintain a 75-year-old airplane, of which there only 1000 or so around, one must know where the parts and knowledge reside. The good news is there are a pretty fair amount of both available. My top recommendation is to join the American Navion Society (ANS) (www.navionsociety.org.) They have a pretty extensive collection of Navion parts, manuals and documentation, and some of the world’s leading experts on Navions. The ANS holds an annual convention that rotates around the U.S. and planned for Culpepper, Virginia in June, 2024. The ANS website will also connect you with other Navion owners who are willing to lend their expertise, provide type-specific instruction and even offer rides to perspective owners to experience the Navion. ANS sells a booklet called “What to Look for when Buying a Navion”, that is a must for prospective purchasers. ANS can also help you find good Navion-knowledgeable A&Ps for pre-buy inspections and maintenance.

Similarly, insurance can be an issue if your insurer does not understand Navions. Those that do understand how easy the Navion is to fly, how ruggedly built it is, and that there really are parts out there, become much easier to deal with. I have been using Ladd Gardner Aviation Insurance for many years. They write a lot of the Navion owner’s policies, and have been reasonably priced and great to deal with.

Overall, the Navion is great airplane for all kinds of missions, a “practical” warbird, great traveling airplane, great short-field airplane and a great IFR airplane. Give a Navion a try, and you won’t look back. As one of our senior ambassadors says: “Go Fly Your Navion!”

—David Desmon, via email

Making sure the PS-5C carb is in working order is essential for the long- and short-term health of the E-series engine. There are a few good shops still out there with a flow bench and an operator who knows how to use them that can keep these carburetors working well.

That said, there’s also a large expense associated with the pressure carburetor if you have to replace the diaphragms. If that happens, consider the STC to convert to fuel injection.

The gear-swing checks aren’t difficult, but pay attention. A hard landing somewhere in the history of the aircraft or poor ground handling with a tow bar can cause a lot of pain and suffering. It isn’t surprising to find some with very old hydraulic hoses, so make sure you service them and the actuators when needed. Luckily the nose and main gear actuators are easy to access. The flap actuator is a little more difficult to get to, but just as easy to service.

—Jeff Sickel, via email