With its pusher engine sticking up high on the fuselage, and a sleek bow that tightly cuts the water line, a Lake amphib has plenty of cool factor. But we’re not convinced these are the most forgiving machines for inexperienced seaplane sticks, and we’re certain you don’t want to buy one that has been neglected, including storage and preventive care.

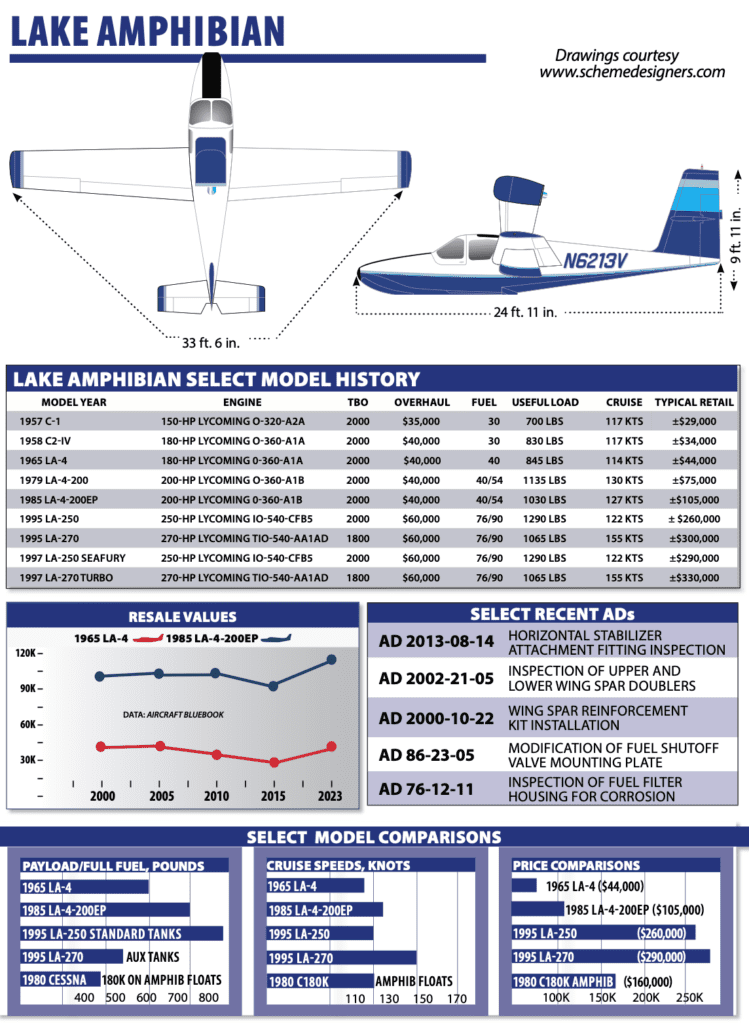

Understand that many of these are old seaplanes—a general design dates back to the late 1950s. But there are newer ones, too, including the last of the turbocharged Seafurys from 1997. As with anything that operates on water, corrosion is a concern. The Lake series was originally developed by Grumman, the maker of now classic multi-engine flying boats, as a potential entry in the civilian market after World War II.

Today, it’s still a popular consideration for those looking for a versatile amphib, quirks and all. Prices are up substantially from just a couple of years ago—at least 25 percent or more.

Before making a deal on any Lake, take it to a shop that knows them well, get an insurance quote and have a solid plan for transition and recurrent training.

MODEL LINEUP

The prototype Grumman Tadpole morphed into the three-seat 150-HP Colonial C-1 Skimmer around 1948. Ten years later it turned into a four-seater—the C-2—powered by a 180-HP engine. In 1960 the Lake LA-4 came along, with an extended bow and longer wings. About 250 Skimmers and LA-4s were built before production ended in 1962. There were some company changes that saw the manufacturing side become a separate entity, called Aerofab. The type certificate was acquired by Consolidated Aeronautics (Conaer) in 1963, which moved its corporate headquarters to Texas but kept the factory in Maine.

The Lake Buccaneer (LA-4-200) was born in 1970 when Conaer put a 200-HP fuel-injected Lycoming on the LA-4. Over the years, a few turbo models were made and at least one non-amphibian water-only model. In 1979, Armand Rivard, an independent Lake distributor, bought the company and moved it to Kissimmee, Florida. He introduced the LA-4-200EP, with a new engine nacelle and its prop shaft extended five inches farther aft. It also had “batwing” fillets at the wing/fuselage junction to improve low-speed handling by eliminating eddies and turbulence that disrupted prop performance.

Rivard also introduced the Renegade in 1979, a six-seat version with a 250-HP IO-540, a beefed-up structure, a rear cabin door and a larger tail. It easily outperforms its predecessors and is even more stable on the water. Good ones sell for top dollar.

Beginning in 1981, the Lakes all got more grease fittings, polychromate primer, an improved canopy and more rust-resistant cabin vents. A turbo version of the Renegade became available in the late 1980s through an STC, so technically it is a mod done by the factory. Its big Lycoming TIO-540 is rated at 270 HP—which, when loaded and piloted right, authoritatively gets the seaplane on the step and flying off the water.

In 1991 the company started making the Seafury, a Renegade with lift rings, survival equipment, a custom tool kit, aux power receptacle and stainless steel brake discs, plus extra corrosion-proofing in an extra coat of chromate primer inside and out and a ceramic coating on the steel parts. Finally, the company developed the Seawolf. It’s a Seafury modified for the military as a patrol, reconnaissance and special ops aircraft that has proved popular on the international market.

Of all the models, we’ve heard the 200EP praised as the best compromise among Lakes between cost and performance. The Spring 2023 Aircraft Bluebook puts a starting retail price of a 1990 LA-4-200 EP at $190,000, but ones with upgrades sell for more.

PERFORMANCE, HANDLING

While Lakes provide the wonderful ability to use runways and remote lakes, that flexibility comes with a price—attaching a boat hull to an airplane means slower cruise speeds and a lower rate of climb than a comparable landplane.

Figure on cruise speeds for a 200-HP Buccaneer in the 105- to 115-knot range with fuel consumption of about 10 GPH. A 250-HP Renegade cruises at about 122 knots, with fuel burns on the order of 14 GPH. The turbo version does nicely up high with cruise speeds closer to 150 knots. We don’t recommend the 180-HP versions unless you are svelte and don’t plan to carry anything.

The EP does better than the Buccaneer, cruising at about 120 knots. It has hull strakes that improve water handling and allow the hull to break free of the water at a lower speed—45 knots instead of 53 for a Buccaneer (50 knots with a batwing mod).

The Lake’s tendency to nose down when power is added and to rise when power is reduced because the engine is mounted high above the CG is one of the many reasons that a thorough initial checkout is in order, in our opinion. Owners reported that it’s wise to practice low-altitude go- arounds because of the nose-down pitch with power—one said, “Cobb the power on a bounced landing, while low and slow, and you’re going to break it—probably badly.” The high rate of accidents following bounced water landings we saw in the NTSB reports seemed to confirm this owner’s concern.

The airplane does not have a deep-V hull, so it does not handle rough water well. In addition, it is a short-bodied flying boat, making it at risk for porpoising.

The Lake accident records are loaded with water mishaps. Catching a sponson in the water landing in a gusty crosswind or touching down yawed can cause an upset and a lot of damage. Bad landings, rough water or boat wakes can end with the Lake trying to play submarine.

In our opinion, it’s absolutely essential—and required for insurance coverage—to get Lake-specific training. The Lake Amphibian Club (www.lakeamphibclub.com) can provide a list of highly qualified Lake CFIs (not to mention knowledgeable Lake shops, an absolute must for any prebuy examination).

LOADING, COMFORT

Useful load in real life averages about 800 pounds for a 180-HP Lake without an IFR panel. It’s about 950 pounds for the 200-HP version and 1200 pounds for the Renegade. Owners tell us that attempting to take off at gross weight on a warm day can provide more excitement and less climb performance than any one pilot needs.

Lakes tend to be nose heavy, a trait that is aggravated by the fact that the CG moves forward as the airplane is loaded. These are not load-and-go airplanes. Having the CG beyond limits for a gross-weight takeoff with a lot of pine trees beyond the beach is asking for trouble.

Fuel capacities range from 30 gallons in the Skimmers and 40 gallons in the old LA-4s. The Buccaneer had a 54-gallon option and the Renegade carries 90. There’s a mod available for the older Lakes to put fuel in the sponsons, adding 14 gallons total.

There is elbow room up front, a bit less in the back. In older models, the hard seats adjust only fore and aft and the cabin is noisy. The EP model has more foam and customized features, and the Renegade has the nicest interior of all; its price reflects it.

There’s no muffler cuff ahead of the firewall to collect heat for the cabin. Through 1973, Lakes used Janitrol gasoline heaters, for which an AD required complete overhauls every two years. Lake switched to Southwind heaters in 1974, but they had only on and off switches, so the choice was cook or freeze. Lake went back to improved Janitrols in 1983.

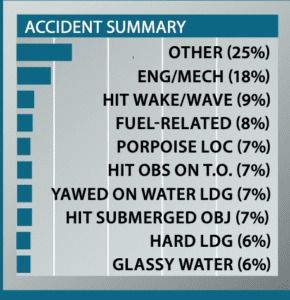

That the Lake Amphibian series of flying boats is anything but plain vanilla became obvious as we conducted our review of the 100 most recent accidents. With virtually all other airplanes, even those on amphibious floats, we expect to see a minimum of a dozen runway loss of control (RLOC) accidents. The Lake series had one, a tribute to its wide-track landing gear stance.

Yet, when the landing surface became liquid, the equation changed radically. We counted no fewer than 50 water landing or takeoff mishaps ranging from touching down while yawed—which usually tore off one of the wingtip sponsons and nearly always resulted in an upset and sinking—through loss of control after hitting a boat wake or large wave, hard landings, landing on the water with the gear extended, hitting a submerged object and not having enough respect for glassy water.

We’ll repeat our concern about touching down on the water when yawed in a Lake and the need to be assertive in avoiding doing so. Bounced landings seem to be an especial problem as after the second or third bounce the pilot loses directional control and eventually touches down with the nose off to the side. With predictably unpleasant results.

There were seven accidents in which the pilot caused the seaplane to begin to porpoise—a nasty form of pilot-induced oscillation specific to flying boats—and did not damp the oscillations. Those increased in amplitude until the aircraft struck the water so hard that it was damaged and sank. In one case, the airplane hit going straight down.

We think highly of the Lake Amphibian series, and its capabilities, but we cannot stress too emphatically the need to get an in-depth, type-specific checkout from someone who knows the airplane well.

Amphibious seaplanes are expensive to maintain and operate, so we were not surprised to see that a significant proportion of the accidents were due to a lack of maintenance. That was the culprit in nearly all of the engine stoppages. Beyond that, hydraulic systems failed because of lack of maintenance and there were three landing gear collapses due to failure to properly inspect components.

When you buy a Lake, make sure the prebuy exam is done with care by a tech who knows Lakes.

As to positive notes, only two Lake pilots tried to continue VFR into IMC and none landed gear up on land.

The Lake is not generally thought of as a short-field airplane. That was confirmed by seven pilots who hit obstructions after takeoff, usually from water.

One Lake pilot made a water landing, taxied to a boat launch, extended the gear and taxied up on to dry land. We think that’s pretty cool. He shut down and drained the water out of the hull compartments in anticipation of further flight. Smart.

However, he then decided to take off from the boat launch, becoming airborne just before the nosegear hit the water. He was observed to fly along, gear down, in ground (water?) effect until hitting a tree branch and losing enough altitude for the gear to hit the water and end the flight.

UPKEEP, OWNERSHIP

Looking for a Lake or need one wrenched? Bruce Rivard’s Team Lake in Gilford, New Hampshire, gets praises for good service and knowledge of the line. The company will help source a used Lake and even handle the transaction, including the prepurchase evaluation. It also has inventory of its own.

“Insurance is getting more expensive as is typical in the market, and I pay approximately $5300 for $1 million smooth liability coverage and $250,000 of hull coverage. This is up from the $4900 I have been paying for the last several years,” Cliff Maine told us. That’s his 1993 Aerofab 250 pictured below.

For a complex airplane that performs in a tough environment, the Lake has amazingly few ADs. Hydraulics are used extensively on the Lake, running trim, flaps and gear all through one accumulator, pump and reservoir. All the actuator static and dynamic seals are plain O-rings and the failure of one will incapacitate the whole system.

All seaplanes leak—it’s a fact of life. The hull of the Lake is broken into compartments with drains at the bottom of each—accessible when the airplane is on land. To purge the bilge water when on the water, there is an electric pump located near the step. So long as the airplane is sitting level, owners tell us that it will get rid of most of the water in about five minutes.

For older Lakes, consider that during the 1960s, the 180-HP models had no zinc chromate treatment and some didn’t have alodine. Check for a faint gold tint to the aluminum on the interior structure of any pre-1970s plane. No tint, no alodine.

A search of Service Difficulty Reports going back a decade did not yield a lot of them. About a third involved cracks in structural components; there was no distinguishable pattern among the remainder. But at this point the majority of aircraft have been fixed. If the wing spar AD has been accomplished, it’s no longer a concern.

“It’s comfortable, but not fast for long trips—around 110 knots at 12.5 GPH,” Dave Ross said of his 1983 Renegade. Ross rightly points out these are complex aircraft and need to be maintained by shops experienced in the type or else there will be an expensive learning curve. “Fortunately, Lake Central in Canada and Harry Shannons Amphibians Plus in Florida are two excellent shops that still support these aircraft and can supply and manufacture parts as required.”