In a fast-changing used airplane market where prices are showing signs of stabilizing, the Cessna 210 Centurion market remains hot, with nicely refurbed turbocharged models selling for a premium.

And you want one that’s been we’ll cared for. In the shop, Centurions are complex retracs, and that means high maintenance costs (and lots of downtime) for ones that have been neglected.

But when it all comes together, Cessna 210 ownership is satisfying. These are go-places singles that—with the right transition training—make for a logical step-up for pilots who learned in Cessna Skyhawks and Skylanes. By demand, here’s a fresh look at the existing Cessna 210 market with a focus on non-pressurized Centurions.

A STRUTTED HISTORY

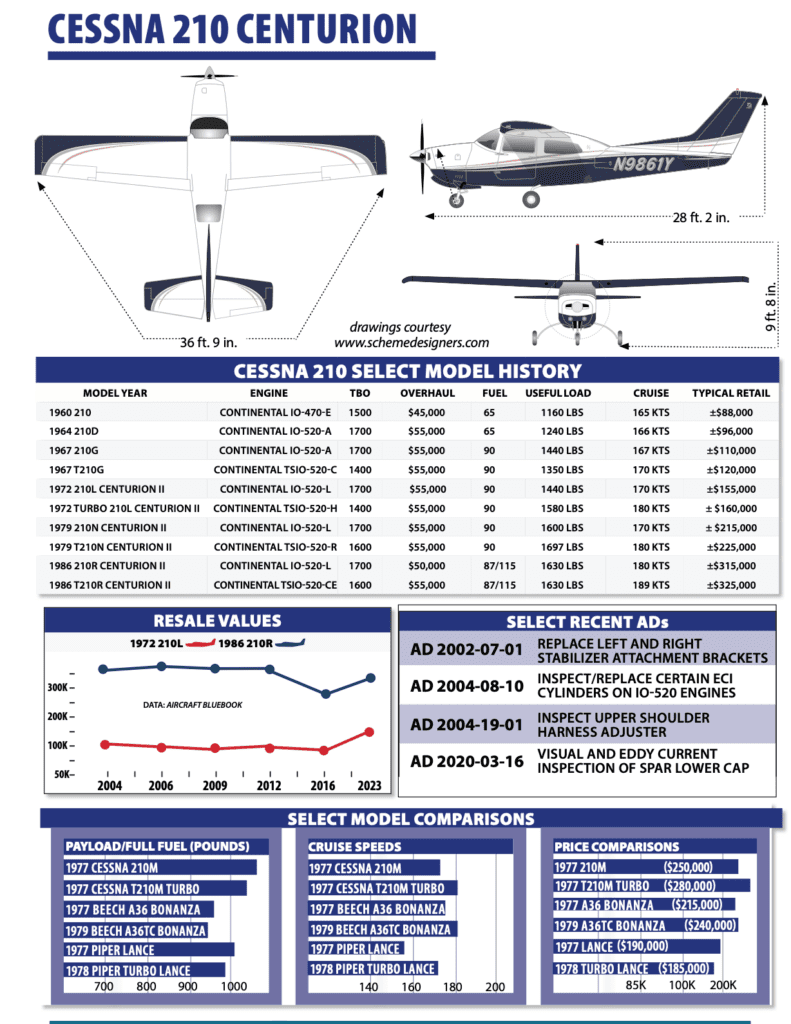

Flash back over 50 years ago when the earliest Cessna 210s—equipped with wing struts—were essentially Cessna 182s with retractable landing gear. It was a winner and the airplane eventually evolved into several versions, including normally aspirated, turbocharged and pressurized models. All are brisk sellers today. But before shopping, know the model line.

In 1967, Cessna replaced the strut-based wing with a cantilevered design. Normally aspirated models were powered by the 285-HP Continental IO-520-J, and by the 1970 model, the 210 had extra baggage space, two additional seats and a 3400-pound gross weight. The next model year saw a boost in takeoff horsepower to 300 HP. In 1977, the 210M came out, with a 3800-pound gross weight, to be followed in 1979 by removing the gear doors for the 210N. Ninety gallons of fuel was standard tankage on 210G through N models.

Only one additional model—the 210R—would come out before production ended around 1986. It had a 300-HP Continental TSIO-520-CE powerplant with a 1600-hour TBO.

The turbocharged models were also retired with the 1986 T210R, by then sporting a 325-HP TSIO-520-CE with a 1600-hour TBO and a 4100-pound gross. Both R models came with 87-gallon fuel tanks as standard and were optionally equipped at the factory for 115 gallons.

SCRUTINIZE THE GEAR

Don’t even think about bringing a Centurion home without doing a thorough prebuy evaluation. Plus, any potential Centurion owner should be aware of main systems and landing gear maintenance history, and systems design varies widely among the fleet. Early on (1972) the landing gear system was reworked to a simpler (although not without required upkeep) electrohydraulic system. Seven years later, the main gear doors were eliminated, which makes for simpler upkeep. (Owners of older models can have their gear doors removed through an STC.) There’s a lot going on when the gear is cycled. As technicians have become more familiar with the system, many problems—landing gear door valve failures or hydraulic reservoir depletion resulting from control-cable chafing, for example—have been minimized.

Gear aside, the airplane doesn’t exactly have stone-simple systems, even if they might make the airplane safer. Cessna pioneered electrical redundancy in piston singles with optional dual alternators and vacuum pumps, which became standard with 1983 models. These days, electronic flight instrument upgrades provide even more backup and redundancy, with some owners opting to remove the vacuum system altogether. Look over the paperwork—including FAA Form 337s and Flight Manual Supplements—to make sure any modifications were done per the regulations and STC.

The service difficulty report (SDR) database shows many gear-related problems in the 210. Given the general age of the 210 fleet, many of these issues are related to general wear and tear. Many of them, too, are related to the system’s general complexity. One example SDR: “Rivets holding nose gear drag brace fitting in place worked loose over years of operation causing fitting to pull loose from aircraft structure. This, in turn, caused nose gear to retract on ground.” The historic nemesis of older Centurions—fatigue cracks in landing gear saddles—has apparently not abated completely. While a repetitive AD from 1976 addresses the issue, it still crops up from time to time in the SDRs. All 210s built from 1960 to 1969 live under the shadow of this problem. With luck, the cracks are found during annual inspections and are fixed in any airplanes now on the market. If for some reason they’re missed, the saddles eventually break and the pilot finds out when one landing gear leg hangs up in the halfway position.

LOADING AND FLYING THEM

Centurions crank out respectable performance numbers, especially turbocharged models that are right at home up in the high teens. Plan on cruise speeds in the 170-knots true range (later-model turbo models that are rigged properly can flirt with 190 knots) and impressive useful loads that can exceed a half-ton.

Based on our extensive experience flying and owning 210s, it’s fair to say the airplane is stable in pitch and roll, although precise pitch trim management is a must. Get sloppy with speed management and hitting the target speeds for approach and landing will be very difficult, although a high gear extension speed helps slow down earlier than other models.

Still, when flown correctly (and when equipped with a good autopilot) the Centurion is an excellent IFR platform—perhaps one of the best available among the competition. But don’t skimp on training, including upset recovery. Although, thanks to limited elevator travel, the Centurion is tough to wrangle into a full-stall break, so there’s nothing particularly nasty about them. Again, a decent step-up airplane.

Folks are also drawn to Centurions for carrying big loads. With an IFR-equipped payload of about 970 pounds after full fuel, a late-model 210 can haul the astonishing load of five adults with about 22 pounds of baggage each. No other single comes close to this except the Piper Saratoga, which rings in about 30 pounds shy and is slower. Moreover, Centurions have an unusually long center of gravity envelope (the longest in its class) that tolerates loading extremes that would make other models in this class virtually unflyable, namely the Bonanza.

As for dispatching in the nasty weather, some owners go the extra mile and install aftermarket TKS anti-ice systems for even more capability. We’re told it adds huge capability to these IFR birds.

COMFORT, BUILD QUALITY

In general, fit and finish in many older Cessnas is not the best and the 210 is no exception: Poorly fitting doors and aging seals occasionally lead to drafty cabins, but many 210 owners in it for the long haul make big improvements to the interior. And it’s not a bad place to dwell on long trips.

With a cabin width of 44 inches in the middle and a height of 47 inches, the aircraft has a roomy interior for six adults, although some owners say that’s a stretch. Still, we used to put six adults in a T210 pretty regularly, with the smallest people in the far aft seat. You could carry full fuel, six 170-pounders and about 10 pounds of baggage. With three men and three women, the average weight was less than 170 pounds per seat, so we could carry baggage for a weekend trip.

Ventilation and heating are generally good except for the rear of the cabin. The trick? With the heat on full, add in some outside air. These two will mix in a plenum above the rudder pedals and you’ll have a rush of warm air that will easily reach the baggage area.

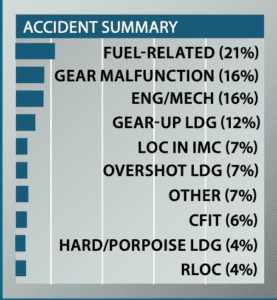

Reviewing the 100 most recent accidents involving non-pressurized Cessna Centurions, we were struck by the number of fuel-related mishaps (21) and the number in which the pilot tried but could not get the landing gear down and locked (16). When one adds the number of times pilots forgot the Firestones (12), the total percentage of landing gear-related accidents rises to a whopping 28.

On the other side of the coin, there were relatively few landing accidents: Four pilots landed hard and/or managed to get into PIO, four lost control on the runway and seven came down final at the speed of heat, eventually touched down and then went off the end of the runway. In general, a 210 can handle fairly strong crosswinds and has excellent manners on rollout, so as long as a pilot can get the gear down, things go we’ll when returning to earth.

The high number of fuel-related accidents was unexpected. About half involved completely running the airplane out of gas. We note that to get the fuel tanks of a cantilever wing 210 all the way full the airplane must be parked with the wings level. We suspect that bit a few pilots. What was concerning was that about half of the pilots ran a tank dry and either did nothing about it or were unable to get a restart upon switching tanks. We can’t help but wonder if they “riched out” the engine by not just turning the aux fuel pump on, but turning it to “high.”

A pilot preflighting a 210 that had been parked outside and not flown for eight months found water and solid contaminants in the fuel. He consulted an A&P who made some suggestions regarding how to ensure that all of the contaminants were removed. The pilot tried none of them. The engine quit shortly after takeoff. Post-accident the fuel lines downstream of the fuel selector were found to contain water and solid contaminants, but no avgas.

A pilot seeking to ferry a 210 for a friend had the fuel selector handle break off in his hand during the preflight. He called his friend, advised him of the situation and said that he’d ferry the airplane anyway. Besides, he’d found a crescent wrench that he said he could use if he needed to change tanks. He then added four gallons of fuel to the selected tank.

As sure as Murphy had a law, the fuel gauge on the selected tank was not accurate and the pilot didn’t stick the tanks. Once underway, the pilot ran the selected tank dry and then discovered that he couldn’t reposition the fuel selector valve with the crescent wrench.

The 16 accidents involving gear that wouldn’t extend and lock had one common denominator—a hydraulic leak in the gear system. If the fluid leaks out, it is not possible to extend the gear. Aggressive gear maintenance is a requirement of Centurion ownership. As is paying attention to warnings—which one pilot didn’t do. Taxiing out the gear down light kept cycling. He launched anyway and couldn’t extend the gear at the destination.

We felt for the pilot who didn’t like the way the flare for a landing was going and went around. His passenger then raised the flaps—causing the airplane to hit the runway so hard one gear leg failed.

MAINTENANCE, MODS

The previous service bulletin requiring inspections of Cessna 210 (models G through M) spar caps turned into an Airworthiness Directive (2020-03-16) that went into effect in March 2020, with compliance due within 60 days or 20 hours’ time in service. The mandatory service bulletin was released after the in-flight breakup of a Cessna 210 in Australia traced to fatigue cracking emanating from a “corrosion pit.” The cost of the AD was generally supposed to be less than $2000 per aircraft assuming no damage is found, but if spar replacement is required if cracks are found, that could cost over $43,000.

Potential buyers should also take care to check the horizontal tail for a variety of problems, including stabilizer and bracket cracking. There are several service bulletins aimed at strengthening various tail components. And make sure the elevator skin itself has not become corroded thanks to water absorption by the foam filler, especially in older 210s. Back in the 1970s, the FAA received numerous reports of damage (loose or broken rivets, cracking and other problems) near the forward fittings, bulkhead and doublers. The problem is confined to fuselage station 209 and Cessna has kits to repair the problems or prevent them from happening. Do a prepurchase evaluation with a shop thoroughly familiar with the 210, and one that can verify all of the ADs have been complied with.

It’s a testament to the 210’s basic good performance that lots of speed mods really aren’t necessary for well-rigged planes. Still, like any high-performance single, the 210 can benefit from the installation of speedbrakes. Both Precise Flight (www.preciseflight.com) and Knots 2U (www.knots2u.net) offer electric-actuated speedbrakes. Along with the 210’s high landing gear extension speed, this makes it really easy to slow down early without terrorizing the engine.

There’s also the gear door elimination mod from Sierra Industries (www.sijet.com). Sierra also makes STOL kits, as does Horton (www.hortonstolcraft.com). There’s also the Vitatoe turbonormalized IO-550 mod (www.vitatoeaviation.com), enabling impressive climb rates while keeping engine temperatures cool.

A permanent addition to our resource shelf is the book Flying the Cessna 210—The Secrets Unlocked by Chuck McGill, www.safeflightintl.com. It’s helped us fly, maintain and report on these aircraft.

The Cessna 210 Owners and Pilots private Facebook group has a lot of active members and is worth joining. As always, we offer our special thanks to this group with a special shout-out to Scott Dyer, Mark Stroud, Steve Mowery and the other active members who have graciously offered up images of their birds and contributed useful feedback for our articles.

WANT ONE?

As noted, you’ll pay a premium for ones with lots of improvements—especially avionics. As we scan the market in early summer 2023, we found plenty of later-model turbo Centurions with low-time engines, new avionics and autopilots, plus nice paint and modern interiors priced we’ll north of $350,000. Older L and N models with good engines, but needing some modern upgrades, still fetch $200,000 or more. Save some bucks for maintenance.

Annual inspections might run around $3000 on the low end to we’ll over $10,000 depending on prior upkeep and the status of those important ADs.