Back in the day, the Cessna 190 series was marketed as the “Businessliner,” although it really wasn’t the first light aircraft to serve a business traveling role. These airplanes are classics now, but still work we’ll for hauling people and stuff just as they did 80-something years ago.

It might look intimidating, but for the skilled tailwheel pilot and well-maintained aircraft, a Cessna 190/195 isn’t tough to fly. Think of it as the link between the poorly harmonized, high adverse yaw radial-engine classics of the 1930s with the feet-on-the floor machines of today, carrying on only the adverse yaw.

A direct descendant of the 1934 C-34 Airmaster, the C-190 series represents a lot of Cessna heritage—it was the first all-metal Cessna, and the last Cessna to be built with a radial engine. That in itself draws buyers to these old airplanes. But owning one certainly won’t be cheap. Here’s a look at what it takes.

MEMORY LANE

The 195 came in as Beech quit building the Model 17 Staggerwing and took its place as a cabin-class bizplane, at a significantly lower cost. The Bonanza came out about the same time, but had such anemic power it couldn’t carry nearly the load and would run out of aft CG quite easily. The Cessna Citation of its day, the 190/195 wasn’t a huge seller, but there are plenty of examples flying. Cessna cranked out 1099 variants of the 190 series—190s, 195s and military LC-126s—from 1947 through 1954. Nearly 80 percent were 195s. The FAA registry lists nearly 700 registered 190-series aircraft, but nobody’s sure how many are actually airworthy. The main distinction among the models is the engine.

The 190 had a Continental W-670 radial pounding out 240 HP and was alleged to be Cessna President Dwane Wallace’s personal favorite. The others had Jacobs R-755 engines of either 300 HP, 275 HP or owner-furnished 245 HP. Most of the 195s were originally equipped with the 300-HP engines, but many have been retrofitted with 275s or 245s. There are still quite a few of the smoother-running Continental-powered airplanes flying, but about half have since been converted to 195s with the Jacobs engines, since the support for the Jake is better.

Owners report that the performance is comparable between the 190 and the “little” 245-HP 195, while the 275-HP and 300-HP 195s are, of course, peppier. The C-195B’s 275-HP R-755-B2 engine is generally considered to be the most reliable of the group, even though all three of the Jacobs engines have the same displacement. The 300 got a deeper intake manifold to get its extra 25 horses, which seems to make it more susceptible to case cracking.

The other significant changes in the airframes over the years were slightly larger flaps along with a modified horizontal tail at serial number 16084. And in 1953, the Goodyear crosswind gear was offered as standard, along with a lighter, springier set of main gear struts. The crosswind gear casters so the airplane tracks down the centerline in a crab but the wheels remain parallel—more or less—to the runway centerline. It looks odd, but works we’ll on those few airplanes that have it.

PERFORMANCE, HANDLING

Above 8000 feet the airplane is an honest 140-knot machine, but down low it is thirsty and slow.

Expect 12.5 to 14 GPH for a normal cruise of 140 knots above 8000 feet; you can burn more, but it won’t go much faster. Fuel burn is something in the high 20s during takeoff.

With 76 gallons of usable fuel on board, you can usually plan on a range of 520 to 780 miles. With the 275-HP Jacobs, count on a cruise of a bit over 130 knots, burning about 13.5 to 14 GPH, at a comfortable and rumbling 1900 to 2000 RPM. Plan on oil consumption of between 0.5 pint to about 1 quart per hour—depending on engine condition. The ship holds 5 gallons of oil when it’s at full capacity.

A pilot has to be willing to put the effort into transitioning into the airplane. The ground handling requires some finesse and the sight picture is unusual. The pilot has to learn how to look straight ahead. Not only does it sit high —which makes for a lot of hard landings as newbies flare too low—the pilot’s seat is angled slightly right and the copilot’s seat is angled left. That means there is a tendency to look across the cowling on landing instead of straight ahead (like a C-46 Commando), which causes problems in the checkout. In addition, if the gear is not properly aligned, the airplane goes from being manageable to turning the pilot into a test pilot. Stalls are Cessna-like, which is to say gentlemanly.

Control harmony is superb, although the airplane has adverse aileron yaw, but pitch, roll and yaw control is beautifully harmonized, and responsive without being twitchy. It feels like a luxury car from the 1950s. Still, the airplane will not stay where you put it. Most have some degree of long-term phugoid, plus they will simply wander after a half-dozen seconds no matter how we’ll trimmed. It’s a fingertip correction, but you have to fly the airplane all the time. Any slop or worn bearings in the control and trim system makes the wandering worse. Nevertheless, it does not wallow in turbulence.

The visibility from the flight deck is really nothing to brag about, since the big engine blocks the view forward and especially to the pilot’s right. Turns during taxiing are a good idea. In flight, the wing’s leading edge is just about at the pilot’s eye level, forcing him to lean forward to see around it. As a minor compensation, the windshield’s top projects we’ll aft of the pilot’s head, as in a Cessna 177 Cardinal, so visibility into a turn is quite good.

The original Goodyear brakes are satisfactory if—and it’s a big if—they are maintained. The Cleveland brake conversion comes from a Cessna 310, a heavier, nosewheel airplane, and are more brakes than the airplane needs. As a result, the pilot has to learn how to modulate them or it’s possible to flip the airplane.

A pilot should be able to both three-point and wheel-land the airplane. Neither is better. However, the power needs to be completely at idle prior to touchdown. One way pilots get into trouble is carrying power through touchdown and then closing the throttle and losing the airflow over the rudder. It three-points beautifully. Once down, the yoke must be pinned fully aft or the airplane will start bouncing. If it starts, full aft yoke stops it quickly. Remember that this is a relatively heavy taildragger with the CG we’ll behind the main gear. If it gets squirrelly on rollout, brakes may not handle it; power and air over the tail and perhaps a go-around are more likely to be successful. Allow a swerve of more than 10 or 15 degrees to develop and there isn’t enough brake to stop it. A groundloop in this airplane will usually cause major damage to the gearbox, fuselage and wings, perhaps even resulting in a total loss.

Potential buyers should have a mechanic familiar with the model check the airplane they have in mind for groundloop damage. If it’s been repaired correctly, no problem, but if not you could be in for expensive remedial work. On an important side note, a prebuy by someone who knows 195s is essential, and a lot of owners have taken serious financial hits by not doing so.

Two types of spring steel gear legs were installed. The later “light” type on the 1953 and 1954 models was thinner and weighed about 20 pounds less. The earlier gear is much stiffer. Aside from the weight savings, the more flexible light gear may be a little easier on the airframe, especially if a groundloop occurs. Among the 195 cognoscenti, debate rages on the use of the crosswind wheels. Some experienced pilots say that only fools fly without them.

Others maintain that with a little care and experience, a pilot will have no problems with the “straight” gear. The Goodyear castering gear was installed as standard equipment in 1953, but due to poor parts availability, not many of today’s aircraft have them. The extra clearance demanded by the swiveling wheels precludes installation of wheel fairings.

Later models have larger air brakes (some people call them flaps) with a lower deployment speed. It was not an improvement as the airplane is so clean that it’s hard to slow down to the white arc.

PAYLOAD, COMFORT, RANGE

Remember, this is a cabin-class airplane, so there’s room to move around in flight. Gross weight of the series is 3350 pounds. A nicely equipped 195 with full IFR avionics and an autopilot will weigh in at 2100 to 2200 pounds, allowing a payload of over a half ton. Roominess is the aircraft’s strong suit, with space for four comfortably, or five cozily. This allows full fuel with Mom, Dad, the kids and a week’s worth of baggage. Reminds you of Grandpa’s old Packard.

In cold weather, the 195 offers instant cabin heat, thanks to a Southwind gas heater located under the rear seat, as in modern twins.

Along with the old-world glamour of the big radial engine comes a healthy dose of fussing, even before you can start the old bird. A lot of the fussing has to do with oil—lots of oil. Since oil collects in the bottom cylinders if the aircraft has been sitting more than a few hours, the pilot must pull the prop through five to 12 blades. This will check for hydraulic lock and allow the start to generate less of a smoke show.

The pilot is not home free during taxiing, either, because many of the old radials’ oil temps begin to heat up with prolonged ground operation. This is one reason Cessna 195 pilots like to avoid big, busy airports with long rides to and from the runway and chances of takeoff delays. Some owners choose to double the cooling capacity by installing a second oil cooler to cope with the problem. Before shutting the engine down, it’s good to pull the prop control to low RPM and allow the engine to idle for a couple of minutes. This gives the engine a chance to scavenge most of the oil that remains inside the crankcase, making a clean start next time at least a possibility. About halfway through this phase, the lineman holding your chocks will develop a glazed-over look of boredom or show his impatience while awaiting your shutdown and fuel order.

When the day’s flying is complete, it’s time to clean up the airplane before tucking it away. That means wipe off the oil, son. While your flying buddies are already tied down and halfway home, you’ll still be wiping oil from the belly of your 195. Radials are notorious for leaking—some say that they just have Alpha personalities and are merely marking their territory—and coupled with the old-fashioned wet vacuum pump, there’s a fair amount of oil that gets deposited everywhere. It’s a labor of love, though, and merely gives you an opportunity to justify a little extra time at the hangar admiring the airplane’s beautiful lines.

Although the engines were designed for 80-octane avgas, quite a few owners report they have used autogas with success and STCs are available to make this a legal alternative. Those who use 100LL commonly use a fuel additive such as TCP or Marvel Mystery Oil to reduce lead deposit buildups in these low-compression engines.

VALUE, INSURANCE

The market usually has a handful of 190 and 195 models for sale, but as one expert put it, “buyer beware.” Unless you really know your way around 195s, arranging for a through prepurchase evaluation is an absolute necessity—no matter how good the airplane looks in person and on paper. And, prepare to pay a big premium.

Inflation and a growing image as a classic have brought the resale value of the 195s to multiples of their prices when new. As with other vintage airplanes, the year of manufacture has little bearing on the selling price. By now, many have been restored, so the quality of the machine and equipment extras are the primary determinants of worth.

In late summer 2022, we hit www.controller.com and other used aircraft sources for an idea of what the market looks like and saw asking prices starting close to $100,000 and nicely restored models we’ll north of $150,000. Moreover, we suspect buyers seem to fit in either of two general mindsets: purists who want nothing less than a showplane restoration just as it shipped from the factory, and those who like the lines and nostalgia, but want a practical flier.

The combination of a tailwheel and an aging airframe has an impact on insurance costs. As we’ve known for a while, that there are fewer underwriters who are enthusiastic about writing policies for 195s than, say, for 180s or 182s.

A private pilot with no instrument rating, 200 hours PIC and 25 hours of tailwheel experience and an extensive checkout might see premiums of about $3000 to $5000 per year, assuming a $100,000 hull and $1 million liability. That’s about the same as a tailwheel Cessna 180 or roughly one-third more than a 182. Experience and ratings lower insurance premiums, of course. But age can substantially raise the premium—or disqualify the pilot altogether.

There’s nothing ordinary about the Cessna 190/195 series. Pilots who want plain vanilla airplanes should cross the last of Cessna’s radial tailwheel firebreathers off of their shopping list.

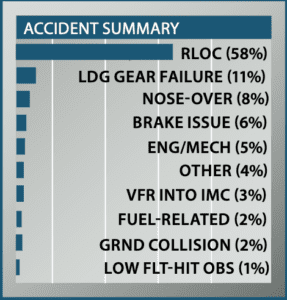

There’s nothing ordinary about their accident record, either. Our review of the 100 most recent Cessna 190/195 accidents revealed a stunning lack of engine stoppage events—only seven. There were but five engine failures, a fourth of what we usually see—no wonder we like radials. Of the two accidents asserted to be fuel-related, both were contamination, one rust, the other water. There were no fuel mismanagement accidents, a tribute to a simple, reliable system.

190/195 pilots demonstrated good weather judgment as well—only three pushed on VFR into IMC.

Where things go south for 190/195 pilots is when the Firestones are in contact with the ground, usually on landing rollout. Of the incredible 58 runway loss of control (RLOC) accidents only a handful were on takeoff. For perspective, tailwheel aircraft average two to three times the number of RLOC accidents of nosewheel airplanes, but we have never seen an RLOC rate above 50 percent for any type of tailwheel machine.

Adding to the unpleasantness, eight pilots got on the brakes so hard on landing that they flipped their airplanes.

We’ve flown 195s off and on for some 40 years, attended the type club’s fly-ins and worked closely with experienced 190/195 maintenance techs. In our opinion, a major portion of the RLOC rate for the marque is a result of improper maintenance—landing gear misalignment and/or tailwheel strut assembly misalignment. Both are critical on the 190/195 series and not a lot of techs know how to do them correctly.

After one groundloop accident, the FAA/NTSB investigation did look into the condition of the landing gear and found that it was misaligned. In another, the ATP-rated owner had only had his 195 a few weeks and was used to having to hold substantial right rudder while taxiing. He told the investigator that he thought that was normal. He lost control during the takeoff roll, went off the left side of the runway and tore up his airplane. The accident investigation found that the recent replacement of the tailwheel strut had been done improperly, leading to a misalignment and the need for rudder during taxi.

In terms of pilot technique on landing, one common mistake was for the pilot to add 10-15 knots on final when dealing with a crosswind, usually then making a wheel landing. They had no problem getting onto the runway, they just couldn’t keep things straight during deceleration on rollout, often with the tail still in the air.

We were unhappily surprised to see 11 landing accidents in which some portion of the landing gear simply broke during a normal rollout. All showed fatigue cracking. Some of those airplanes had been groundlooped previously, apparently stressing the gear.

Our take? If you’re considering a 190/195 purchase, have a type-knowledgeable tech inspect the gear carefully for alignment and cracking and get a through checkout.

MAINTENANCE

As one 195 guru put it, “There are three rules for long-term happiness with a 190/195. Gear alignment is crucial, the brakes must be we’ll maintained and the tailwheel strut and steering must be we’ll maintained.”

There will be a long history to consider on any 190/195. Consider that by the time the 195 fleet reached 10 years old, many had been parked in the weeds because everyone wanted faster, sleeker, flat engined, retractable tricycle gear equipped planes. Worse, the only airframe maintenance publications available were the ones Cessna prepared for the military, and we’re told there was never a civilian maintenance manual. And to get the military books, you had to know where to find them.

These pubs had huge gaps in them and left those maintaining 195s to literally improvise or make their best guess on how things were supposed to go together. As a result, most 195s fell into disrepair and by the 20-year mark, a lot were abandoned in tiedowns or left to rot on grass strips in the middle of nowhere. Soon, a small number of aviation lovers, realizing what incredible bargains these planes were, started delving into the 195 and filling in the blanks.

Today, the operational and maintenance knowledge on these airplanes has reached a highly developed state. Companies like the 195 Factory in New York, Butterfly Aviation in Kansas and Heritage Aero in California specialize in maintaining and supplying parts to the fleet. Also, Air Repair in Mississippi and Radial Engines Ltd. in Oklahoma specialize in rebuilding Jacobs and Continental engines.

For airplanes that got behind the maintenance curve, the new owner will invest a little more effort into keeping the plane flying because Businessliners are rare, and fewer mechanics are familiar with the old radial engines and their archaic accessories. Access to the engine accessories is made easier by an engine mount design that allows the powerplant to be swung out from one side, as on a hinge. The first time an onlooker raises his eyebrows at the unusual sight of the engine being canted about 15 degrees to the left, he’s usually mockingly told that “Oh yeah, this 195 has the crosswind engine.”

As for annual inspections, only the price of the inspection itself is comparable to other singles. The number of repairs on the aging airplane usually bumps the price up to a notably higher number.

One common problem with the 195s is a leaking oleo tail strut. Generally, a good overhaul with proper seals will correct this, but some believe servicing it with Granville Strut Seal might be the answer.

Tailwheel strut maintenance is a big deal, perhaps fraught with denial and ignorance. It’s not hard to do, it just has to be done right by someone who knows how. If the chrome inner strut is pitted, it won’t hold pressure; it must be smooth. Never put a spring in the strut—it turns the tailwheel into a pogo stick. Never fly the airplane with the tailwheel strut flat—it will damage the tail.

Insofar as ADs go, there aren’t many, considering the 60-plus-year age of the airplane. Only four require recurrent inspections. There are no ADs on the engine or propeller, something that strikes us as a record of sorts. All the Jacobs and the Continental engines go about 1000 to 1200 hours to TBO.

PARTS, SUPPORT

Despite the fact that these days Cessna provides little more than moral support, owners report that the parts situation isn’t too bad, although the supply chain issues haven’t spared them. In addition to some parts being available from Cessna (albeit pricey), The 195 Factory (www.the195factory.com) can provide most airframe parts from new manufacture. Heritage Aero (www.heritageaero.com) has many spares for the straight and crosswind Goodyear wheels and brakes, in addition to instrumentation and providing maintenance.

You might not be we’ll served by taking your Businessliner to the local Cessna boutique for service—you could find yourself paying for the learning time of the technicians. Recently the International Cessna 195 Club (www.cessna195.org) has begun hosting owners’ maintenance forums at strategic locations across the U.S. to improve the awareness of the airplane’s special needs. The program offers an opportunity to spend time with “195 professionals” who provide hands-on insight by accompanying the owner and his mechanic in inspecting the few areas that are unique to the type.

Recently overhauled Jakes are alleged to rival flat engines in their oil use. Some parts for the Continentals are scarce, although rebuilders can make do with used, serviceable parts. The R-755 Jacobs are we’ll supported with many new and modernized parts available. The R-915 330-HP Jake is not an orphan, but not nearly as we’ll supported as its smaller sibling.

MODIFICATIONS, CLUBS

For safety, retrofitting retractable shoulder harnesses (B.A.S. and others) improves survivability in the event of an accident. And the lap belt’s attachment point is relocated from the seat frame to the floor where it can actually do some good.

There’s a popular locking tailwheel (The 195 Factory LLC) that many feel tames the beast’s ground handling.

Hartwig Fuel Systems (formerly Monarch) makes a replacement fuel filler cap that’s designed to repel water and also has individual venting. It’s STC’d for most Cessnas, but not specifically for the 195, so a field approval will be needed.

Although the Lear L2 was the factory-optional autopilot, we note that Brittain has an STC for its B2C system and Genesys for its S-TEC series 30 and 55 systems. (Lots of luck getting repairs on the Lear, by the way.)

Any of these do an adequate job, but we were not able to identify any maker who has certified a yaw damper. This would be a welcome addition due to the aircraft’s considerable adverse yaw characteristics.

Judging from the comments of owners, one of the most useful conversions is from the troublesome Goodyear brakes to Cleveland brakes, which are many times more effective. For increased convenience, the addition of tail push handles (B.A.S. Inc.) helps move the airplane on the ramp.

Avionics upgrades for the 195 can be a challenge. The huge oil tank lives behind the instrument panel, thus requiring radios of short depth, and the engine’s noisy ignition system was designed in 1934 when radios weren’t even on the engineers’ scratch pads. A significant tab can result from the avionics shop’s chasing of the elusive electrical noise source.

Radial Engines Ltd. has been issued an STC for a fuel-injection mod for the Jacobs 275- and 300-HP engines that reduces fuel consumption and evens out fuel mixtures to the cylinders for smoother operation and greater power. The engine originally had only an oil screen. Many have been retrofitted with oil filters from ADC, Air Wolf or other field STC sources. Visit www.airwolf.com.

In addition to the Jacobs and Continental engines that Cessna installed on the planes at the factory, the years have witnessed STCs for a few other engines. Perhaps the most common is the Jacobs R-755’s big brother, the L-6. It provides 330 HP for takeoff.

In the 1960s, Page Aircraft Engines adapted a turbocharger, resulting in the R-755S; it’s rated at 350 HP for takeoff/300 HP continuous. Western owners praise the performance improvements for mountain flying. The King Kong of all Cessna 195s resulted from Parks Aviation installing a Pratt & Whitney R-985 with a whopping 450 HP to improve the climb and high-altitude characteristics for aerial photography.

There were only a handful of the latter planes built by Parks—they carry the model designation of “196” after the mod. Most have tip tanks to accommodate the higher fuel flow, but at least one has higher capacity tanks installed in the wings to provide 100 gallons of useable fuel.

The original 10.00 SC smooth-contour tailwheel tire and tube is available, albeit expensive. Some owners have converted to a tailwheel that uses the same tires as a Cessna 180, a much cheaper alternative. They’re available from R-R-R-Russ Aircraft Supply. (See www.russaircraft.com.)

The aforementioned International 195 Club has a broad membership and hosts annual fly-ins at various locations in the U.S. Its website has a hangar talk bulletin board where information is shared and the club publishes a quarterly bulletin for members. It has many technical materials and support information. On Facebook, there’s the 2100-member Cessna 195 club.

OWNER FEEDBACK

I purchased my Cessna 190 about four years ago from a gentleman who owned the plane for 48 years. This is not uncommon in the 195 community, which says something to the aircraft and each owner’s fondness for their machine. The Cessna 190/195 satisfies my classic airplane desire while also having the utility to be a capable traveling airplane.

When I bought the plane, I was a bit nervous about the maintenance requirements. It was my first round-engine airplane, and I had heard all of the lore of difficult operating practices. While it does take some slightly different techniques to operate, they are not challenging. The International Cessna 195 Club steered me to an amazing group of mechanics and shops that specialize in supporting the plane. The unique maintenance practices are we’ll covered and the parts support is fantastic. My annual costs would be about the same as other aircraft of this size, but I spend a bit more each year to upgrade something on the plane. Most owners choose to have maintenance accomplished by a mechanic familiar with the type as the landing gear box, tailwheel assembly, door posts and a few other areas benefit from an expert inspection. Although one could probably have this plane maintained without any personal involvement, I have really enjoyed assisting with the maintenance and learning more about this beautiful machine.

The Cessna 190/195 is a wonderful aircraft to fly, but I am very glad I received a thorough checkout from an instructor familiar with the type. First, the sight picture on the ground is unique. You are nearly blind out of the front right quarter of the plane when taxiing. You will often make “S” turns to get a better view when taxiing. The two front seats on the plane are set at a slight angle toward the center, so what you feel is straight when landing is actually slightly askew. After a few hours you get used to the sight picture, and it becomes a non-issue. The plane also has a relatively small rudder and there is a lot of mass back there, so make sure you are straight at all times during takeoff and landing. Gear alignment is critical to manners on the ground. An experienced 195 mechanic can tame a squirrely plane with a proper gear alignment. Once in the air, the plane has great forward visibility and the greenhouse windscreen allows a wide field of view in turns. The controls are we’ll balanced and lighter than you would expect for a plane this size. My 190 cruises about 130 knots, whereas most 195s seem to do about 10 to 15 knots better—pretty respectable for a 75-year-old design.

From an insurance standpoint, the 190/195 seems to follow the same rules as most other tailwheel aircraft of similar weight. Tailwheel time, recency of experience and hull value appear to have the greatest effect on premiums. My insurance company insisted that I receive my checkout from an experienced 195 instructor. I have heard that some insurance companies are starting to require periodic training to maintain lower premiums, but I haven’t personally experienced this yet.

There were two pieces of advice I was given prior to the purchase by several 195 owners I had reached out to prior to purchase. The first and most important piece of advice was to join the Cessna 195 International club. It is one of the most active aviation type clubs around, and the club has made ownership a joy. I have found a forum discussion and personal support on every challenge I’ve had with the plane to date. The second piece of advice given was the importance of a prepurchase inspection by a mechanic familiar with the 195. That inspection could really save you from expensive repairs later.

Bill Sponsler – via email