That’s Mark Kolanowski’s A150K aerobat in the lead photo (credit for the good air-to-air snap goes to Gage Altrock). Kolanowski said his 150 is a good camera plane partly because it flies we’ll hands off, and fine course corrections can be made by weight-shifting and opening windows.

They don’t break any high-speed records or enjoy cavernous cabins, but owners seem to love their 150s and 152s. With the oldest models 65 years in age, and whether for training, traveling (slowly) and even aerobatics, the venerable 150/152 series soldiers on as an honest and durable two-placer.

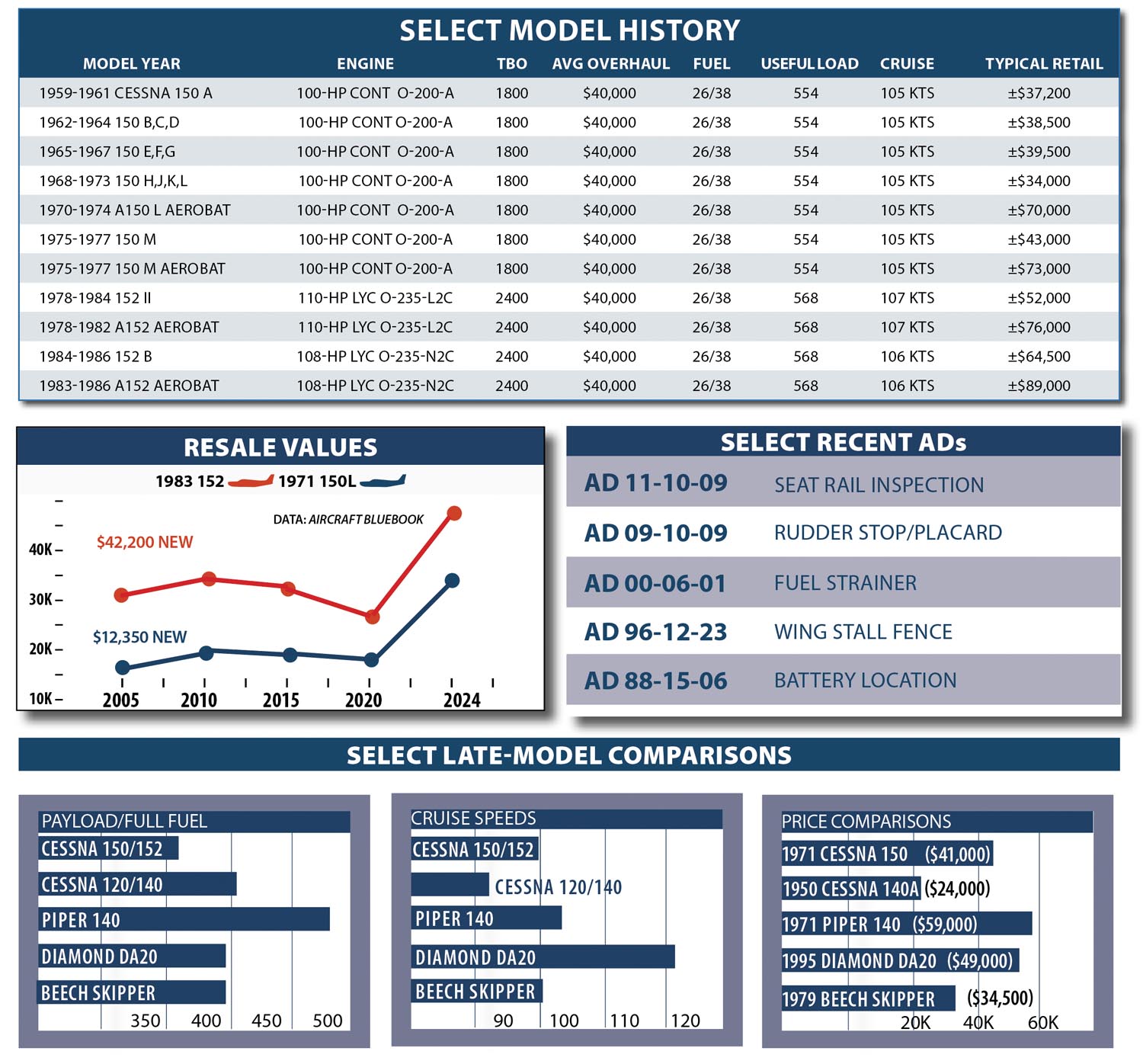

But don’t count on many turnkey bargains. Models with recent engine work, new avionics and other improvements push the $50,000 price point—up even more than when we looked at the market a couple of years ago. Ones priced on the cheap will likely need lots of attention. Ready to close a deal on a 150 or 152? Find one with no corrosion, good maintenance records and upkept aesthetics.

Choose your model

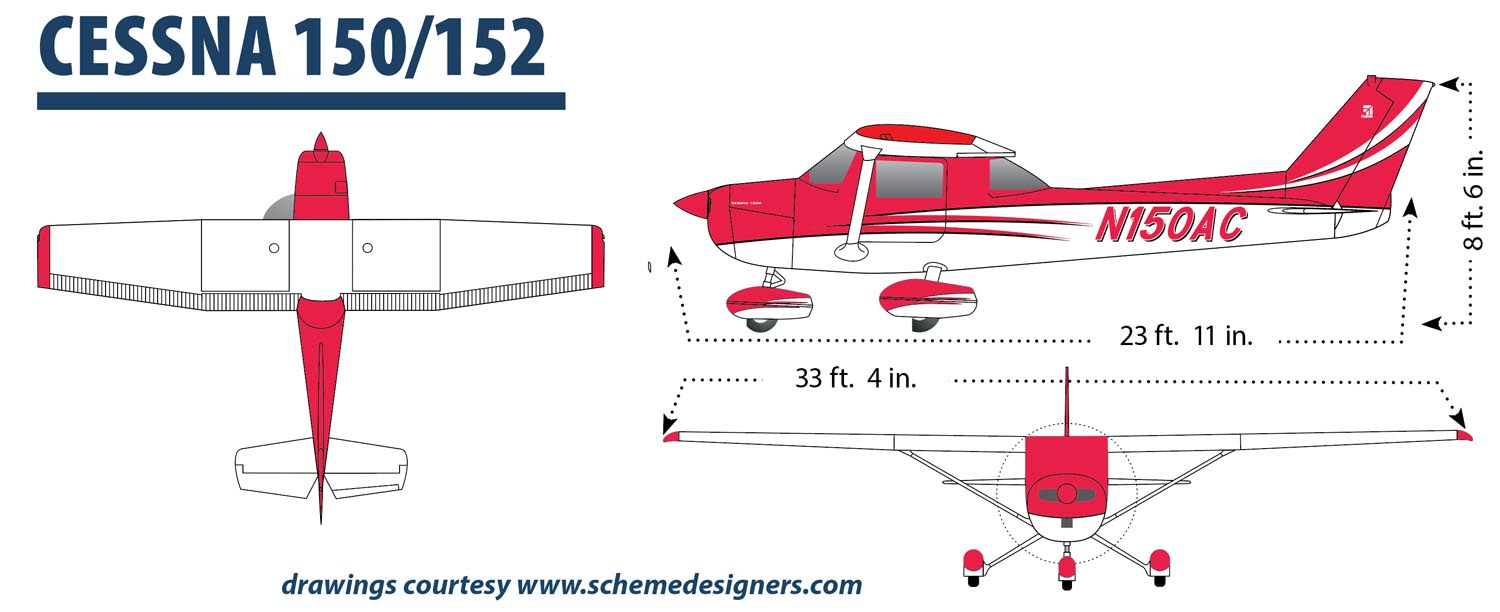

In doing so, you’ll need to look back to 1959, when the first of the 150s came to the market. The first 150s have a real vintage vibe with their squared-off tails and a turtledeck-style fuselage with no rear window. Improvements in styling were inevitable and in 1961, the first of many changes in the model began, starting with moving the gear struts aft two inches, which cured the airplane’s tail heaviness. Ten years later, tubular gear legs with a wider track were added. In 1975, a larger fin and rudder were added and before that, electric wing flaps were installed. Previously, the flaps had been manually operated and some pilots who like it simple complained that electrics were a bad decision. We’re not sure that argument can be won to this day, though we like simplicity from a maintenance standpoint.

Weight should be a concern when choosing a small two-placer. While the little 150 began life as a 1500-pound airplane, by 1978, the gross weight had been bumped up to 1670 pounds for the 152. For a two-place airplane, that’s a big increase and it could make the airplane more desirable in today’s market where people and the stuff they bring aboard are heavier.

By no means do any of the 150/152 models offer spacious seating. Fill both seats and the occupants sit shoulder-to-shoulder, leg-to-leg. Yes, you wear these airplanes and egressing and ingressing aren’t exactly glamorous.

Light on performance

Owners love to travel in their 150s and 152s and just accept that they shouldn’t be in a hurry. Plan on fuel stops, of course, and range isn’t bladder busting. Fuel capacity is 26 gallons (38 with long-range tanks) and owners tell us they generally flight plan for 95 knots at 5.5 GPH. That will give a three-hour endurance, with a one-hour reserve. The baggage area can accommodate up to 120 pounds of stuff—which isn’t awful. But don’t plan on loading big items. We’ve loaded small folding bikes and limited camping gear.

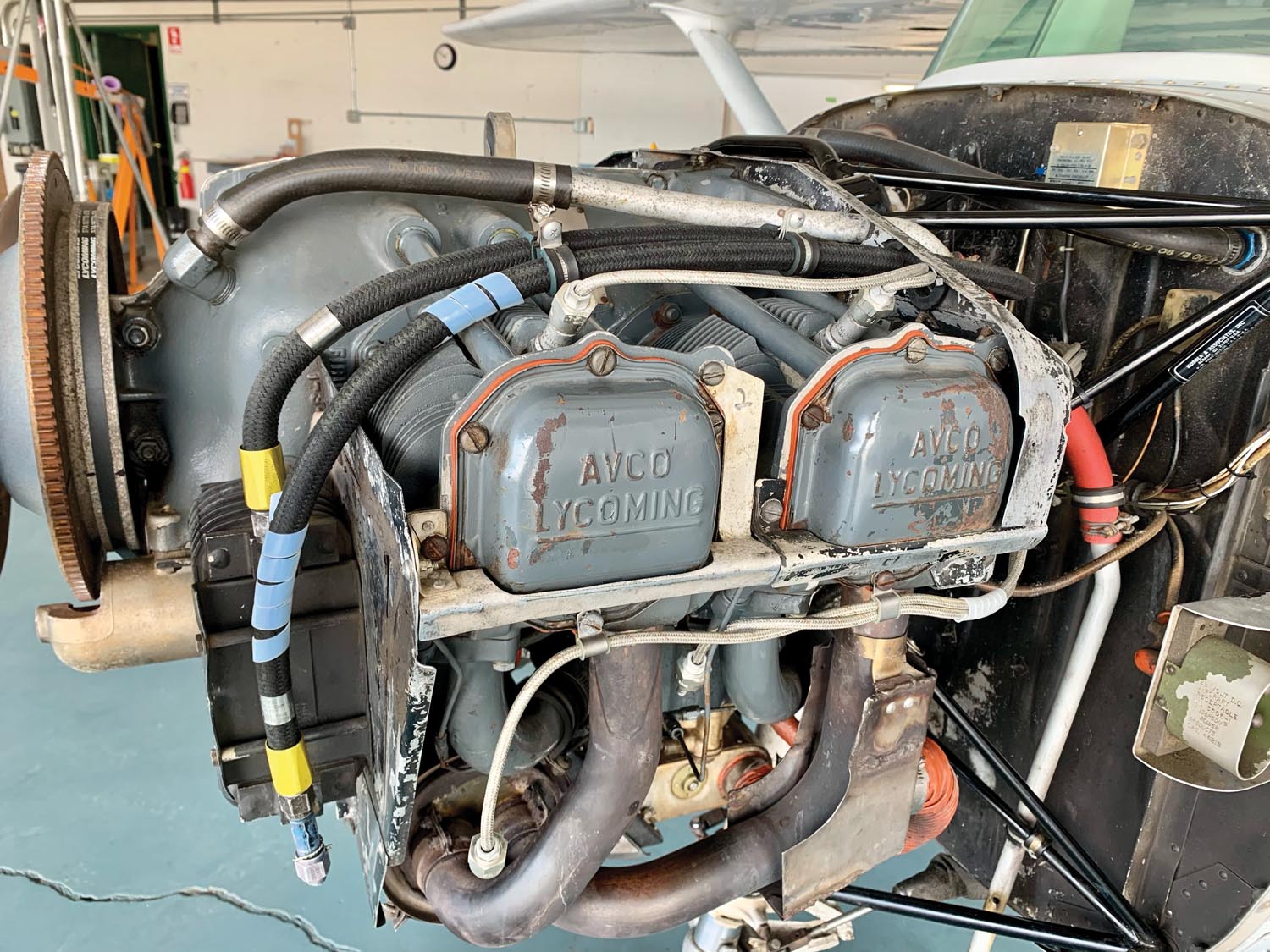

As for powerplants, early 150s had reliable and easy-to-wrench 1800-hour-TBO 100-HP Continental O-200s. When 80/87 fuel began to fade from the market in 1978 and was replaced by 100LL, Cessna switched to the 110-HP Lycoming O-235. It had more power and the TBO was 2000 hours and eventually 2400 hours. The 152 II was born in 1978 and it had a 28-volt electrical system, a one-piece cowling, redesigned fuel tanks and 40 pounds more useful load than the earliest 150. Still, performance was generally unchanged.

Owners tell us that early models can be stubborn to start because of weak spark and lack of a priming plunger. Cessna later added impulse coupling on both magnetos to improve this, plus direct priming for each cylinder. The airplane eventually got a split cowling because techs understandably complained about having to remove the prop to uncowl the engine. And since lead fouling was a wart with the O-235-L2C engine, it was replaced by the N2C variant on the 152B model in 1984—an engine that was used until the line shut down in 1986.

Inspect it right

You’ll need a good eye when searching the 150/152 market and our advice is to avoid high-time models that have lived hard lives on training lines. While the 150/152 is more robust in the hands of students than most modern LSA models, it’s not uncommon to find ones that have been pranged. Look for evidence of nosewheel work or firewall damage—especially on ones used for training.

The 150/152 series has what we would call an average list of ADs, none of which are particularly onerous or expensive. The major safety-related item is the seat track AD, which prevents the seat from unlocking and sliding rearward. Most aircraft should have had this done long ago.

But keep on top of the maintenance and you should be rewarded with easy annual inspections. Owners who do the right things tells us they see invoices for annuals that are in the $1000 to $1500 range.

In our view, an absolute must-do for anyone even remotely interested in buying a Cessna 150 or 152 is to join the Cessna 150-152 club. You’ll find a wealth of knowledge on a wide variety of topics. Find them at www.cessna150-152club.com. Also, for a detailed book on flying and operating Cessna 150s, contact Arman Publishing at www.Cessna150book.com.

Speed, handling

Top speed for the 152 is given as 109 knots, although we think that’s quite generous for stock airplanes. The ones we’ve flown have a sweet spot at around 95 knots. It’s about the same as the Piper Tomahawk and two knots faster than the Beech Skipper.

Handling is what it is, which is predictable, with relatively light control forces and no nasty stall habits, although do watch for a break-off that can progress to a spin. Still, the Cessna 150/152’s slow flight characteristics are so utterly benign that they nearly qualify as STOL airplanes. The large flaps—even when limited to 30 degrees—are quite effective, although they do generate quite a nose-down trim moment. This is easily handled, although the control forces escalate somewhat.

Students have to be taught to watch for abrupt nose-ups when applying full power for a go-around, training that prepares them nicely to transition into the Cessna 172, which has the same characteristic. The airplane is comfortable with an approach speed of 60 knots or slower, but it will easily tolerate higher speeds, because those draggy flaps bleed off excess airspeed in a heartbeat. Land it fast and it will bounce. We think the 152’s runway performance is good, especially if the airplane is light. It’s not as good when heavy on a hot day. With a portly CFI and student aboard, more than a few 152s have trimmed the trees off the end of runways.

Owner comments

I’ve been the proud caretaker for a 1970-model A150K Aerobat for nearly two years, and it’s taken me through the completion of private training and into the world of F.A.S.T. formation flying in the 250-plus hours she’s been under my care. My particular airframe had a Lycoming O-320-E2D installed in the 1990s, and has been a stellar performer as a result of this STC.

For me, as an air-to-air (and air-to- ground) photographer, the high wing of the 150 stays comfortably out of the way for photo operations from either of the front seats, and the plane can work quite we’ll in that role as long as the subject aircraft is speed compatible. Even with the larger engine, the 150 is still a very economical aircraft, with relatively low insurance rates and reasonable fuel burn. Even at max gross, this upgraded 150 has no qualms about climbing, with rates comfortably over 600 FPM even on a hot and humid summer day, where 1100 FPM on takeoff is not uncommon in the cold winter months, and it can get in and out of relatively tight fields without much difficulty.

Being such a common airframe, parts support seems to be plentiful, though some of the STC-specific components are rather difficult, if not impossible, to source and may require more effort to correct or change when things break.

—Mark Kolanowski, via email

My 150 (Woodstock) spent the first 10 years of its life doing what Cessna 150s do best—operating as a trainer. In the mid-1980s it was converted to a Texas Taildragger for banner towing. The main gear was moved forward, the nosewheel removed and a tailwheel installed, a STOL kit installed and the original 100-HP Continental O-200 engine was replaced with a 150-HP Lycoming O-320-E2D. With the upgrade, the gross weight went from 1600 pounds to 1760 pounds. Some of that was eaten up by the increased weight of the new engine, though it does allow for more useful load with full fuel.

At 1700 hours, the time has come to decide on what to do with the engine. With parts supply chain issues, I didn’t want to have the plane grounded unnecessarily so I decided to order a factory rebuilt engine from Lycoming. The order ($40,000—doubled from 1994) was placed back in December of 2023 and I should have the new engine sometime in August of 2024. The Lycoming O-320 is a great engine and I could probably go longer but I wanted to do the work on my timeline and my terms rather than have the engine condition determine when I would start waiting for parts.

Over the years I’ve always been looking for meaningful modifications to make to the airframe that improve reliability and safety. The extra 50 horsepower in the engine does wonders for the climb rate. Even at full gross weight on a warm summer day I still see better than 500 FPM in the climb. When lightly loaded on a cool winter day, the climb rate typically exceeds 1000 FPM. There is some improvement in the cruise speed, but it is still a draggy Cessna 150. I plan on 100 knots and adjust for winds.

One area of performance in which the engine really shines is on the go-around. With the flaps down at the full 40 degrees, I can apply full power on a go-around and start to climb. Once the climb is established (or the descent is arrested) I can start bleeding the flaps off without worrying about sinking into the ground.

Insurance for the tailwheel is about $800 per year. My only claim was a prang from taxiing into the ditch back in 1997. The grass in the ditch was cut the same height as the grass in the surrounding area so I didn’t see it until the main fell into it and the propeller started spewing up dirt.

Annual inspections run about $1200, and the cost to own the plane (insurance, annual and hanger) comes to $7520 per year, or about $75 per hour of flight time (based on 100 hours per year). Direct operating costs (figuring an engine fund of $20 per hour or $40,000 at time of overhaul) is about $70 per hour. Not the cheapest hobby around—but my Texas Taildragger 150 is fun, fun, fun nonetheless.

—Ed Figuli, via email

Given their widespread use as trainers, we weren’t surprised to find that 36 percent of the 100 most recent Cessna 150/152 accidents were landing related. (We looked at 70 150 and 30 152 accidents to approximate the number of each type built.)

OK, we were a little surprised— we thought that the percentage would be higher.

We get what we call landing related accidents by combining runway loss of control (RLOC) events, hard/bounced landings and loss of control (LOC) on go-arounds. Because we’ve seen similar numbers on aircraft that are not considered trainers—and much higher numbers on tailwheel airplanes (although at least two of the landing accidents were on tailwheel-converted 150s)—we came to the conclusion that the 150/152 series rightfully earned the reputation as the most popular trainers in history because they aren’t that terribly hard to land and they have more than adequate control authority for most conditions.

We were impressed by the pilot who made a hard landing and realized that repairs were needed. He hopped in and flew to his local shop—where he landed so hard that the nosegear collapsed.

Despite good landing manners, the marque has light wing loading and care must be taken to position the ailerons correctly on windy days—we found a report on one that was blown over when taxiing.

Despite good landing manners, the marque has light wing loading and care must be taken to position the ailerons correctly on windy days—we found a report on one that was blown over when taxiing.

There were only seven engine stoppage events that were due to mechanical issues, or unexplained, a low number, in our opinion, and partially due, we think, to the fact that training airplanes are used a lot, avoiding one of the toughest environments for an aircraft engine—sitting unused.

There were, however, nine events linked to carb ice, which may be conservative. For both the 150 and 152 it is our opinion that a pilot’s first reaction if the engine sputters, belches or quits is to pull the carb heat knob on and leave it on long enough to be effective.

We found 15 fuel-related accidents. Almost all were simple fuel exhaustion, most after taking off with partial fuel and a less than careful effort to determine just how much was in the tanks. Normally, fuel exhaustion accidents go up as the number of tanks to manage go up, so here the pilots were able to defeat a dirt-simple, on or off, fuel system.

We noted three fuel contamination events—in each the pilot did find water on the preflight and said he’d kept sampling until the samples were clean. We note that a lot of 150s and 152s we’ve observed have a plug rather than a quick drain in the low point of the fuel system—under the belly. It’s our opinion that if water is found in the wing tanks or fuel strainer, it’s essential to drain the low point of the system and potentially get a mechanic involved to ensure all contamination is removed.

Finally, there were more than 15 accidents connected with takeoff attempts from short fields and/or go-arounds. Those included hitting obstructions after lifting off and stalling on climbout. We think that the modest power of a 150/152 has to be respected, especially with two aboard, and at least a 50 percent safety margin added to POH takeoff distance numbers.