In the world of Beechcraft step-ups, pilots might start in a Bonanza, move to the Baron and for those not ready for a King Air, consider the Duke.

Far from inexpensive ownership, the right Dukes (ones with good upkeep and upgrades) can be good airplanes that serve serious, all-weather traveling. Up a few more notches is a turbine-converted Duke. Of course, like any high-end pressurized cabin-class piston twin, get an insurance quote before shopping and bring your A-game when flying it home.

HISTORY

The earliest Dukes are old airplanes—dating back to 1966—and Beech kept the line going until 1982. If you’re shopping other brands, the Duke generally competes with Piper’s P-Navajo and of course the Cessna 414 and 421 pressurized twins. Although, we’ve heard from potential Duke buyers also shopping for pressurized Barons.

The Duke was advanced in its day thanks to manufacturing processes and materials, and that included skin bonding, honeycomb panels and chemical milling, plus magnesium was used in the empennage. The landing gear is classic Beech, being essentially identical to the smaller Baron’s.

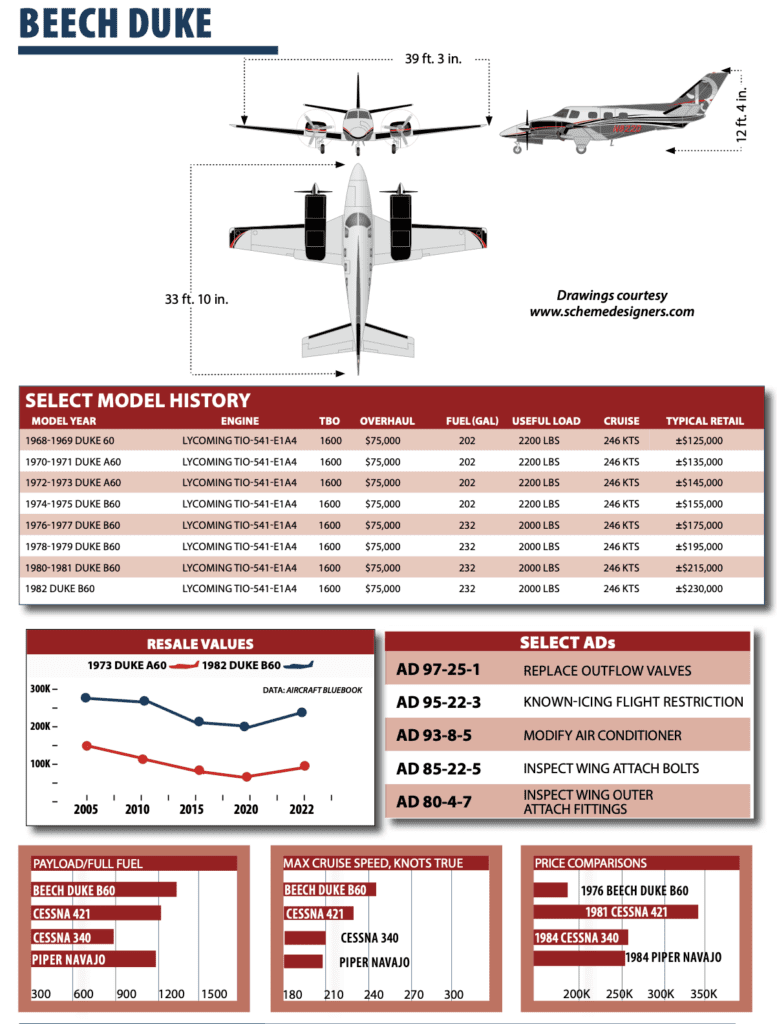

Beech didn’t change the Duke much over the years, although there were three models to include the straight 60 (sold in 1968 and 1969), the A60 (1970 to 1973) and the B60, introduced in late 1973 with airframe number 247. The fuel capacity was bumped up from 202 to 232 gallons in 1976. All told, 596 Dukes were built.

The model progression represents steady refinement, but the airplane’s configuration remained basically unchanged. In 1970, the Model A60 was introduced with a modest increase in gross weight (up 50 pounds from 6725 to 6775), but useful load and performance dropped a bit. According to book figures, the straight 60 is a much better short-field performer than the A60. However, Duke owners tell us those early figures were extremely optimistic, and that the A60 is only slightly inferior in takeoff and landing performance to its predecessor.

One difference among the three models concerns the exhaust stacks. The original 60 had the shortest stacks, and suffered from flap corrosion due to the impingement of exhaust gases. The A60 had longer stacks, but corrosion was still a problem. The B60 has the longest.

All Dukes are powered by 380-HP Lycoming TIO-541 engines. The slightly unusual powerplant has the turbocharger designed as an integral component, rather than added on as an accessory. Early models installed on the 60 and A60 were maintenance headaches and had 1200-hour TBOs. But the engines have been upgraded over the years and now have a 1600-hour TBO; it’s unlikely that many of the 1200-hour engines are still in service. Several Duke owners, in fact, tell us they’ve gone we’ll past that figure by operating the engines properly and, in particular, ensuring that they are properly warmed up and cooled down to avoid shock cooling. It’s advice worth taking, given the number of cylinder problems we’ve heard about.

PERFORMANCE

Don’t expect King Air speeds, but the Duke is faster than a Baron, but on more fuel burn. Realistically, at 24,000 feet the max cruise is about 220 knots (250 MPH) at 65-70 percent power. Fuel consumption is about 40 GPH. One Duke owner told us he flight plans 52 gallons the first hour, 43 gallons for every hour thereafter and uses 68 percent power. Pulling the engines back to 55 percent power, fuel consumption drops to about 30 GPH, but the speed drops to about 185 knots.

Hardly blistering fast, but the Duke edges out other pressurized twins in performance, with one exception, the pressurized Aerostars, which fly 10-15 knots faster on about 25 percent less fuel. Using high power settings for speed has a price, though: One owner called the cabin noise level “unbearable” at 75 percent power. Bring along your best ANR headsets, and consider modern interior upgrades.

Although the Duke’s range is rather limited—its standard fuel tanks hold just 142 gallons—most have optional long-range fuel tanks that hold from 202 to 232 gallons, depending on the model. Top off the optional tanks and you can boost up the manifold pressure and make a four-hour, 900-NM trip with IFR reserves. At reduced power and full fuel, you can fly the Duke 1000 NM, which is average for its class.

The Duke wasn’t designed for short runways. Most owners say they won’t even think about using anything with less than 3000 feet. One owner, though, says he regularly flies his Duke out of a 2650-foot runway in Pennsylvania.

This compels us to repeat an old but true story about how motorcycle daredevil Evel Knievel once ordered the pilot of his Duke to land on a drag strip. The Duke ended up with its snout through a truck trailer Knievel used as a dressing room. Another limitation of the Duke is that its initial climb on takeoff is rather lethargic until it reaches about 500 feet, according to some owners.

Climb performance is important for a pressurized airplane designed to cruise above 20,000 feet. Here, the Duke turns in respectable performance once it gets going. A climb to 24,000 feet, at full gross on a warm day, takes just 28 minutes, reports one corporate owner. Others say the airplane climbs 700 to 1000 FPM, depending on weight.

The addition of intercoolers improves climb performance and offers other benefits, though some say they think the benefits of intercoolers are dubious. At any rate, the Duke’s climb performance (once it settles into the climb) is generally considered superior to any other owner-flown pressurized twin—except, again, for the pressurized Aerostars.

Single-engine performance is about average for this class of airplane. In other words, you’ll be mumbling curses and prayers when an engine quits, even under ideal conditions. Expect a climb, at full gross weight and sea level, of 307 FPM (this assumes a perfectly running airplane flown with flawless technique).

Service ceiling with one dead engine is 15,100 feet. Some pilots say that intercoolers improve single-engine performance. The addition of vortex generators goes a long way toward improving single-engine performance. As always, we heartily recommend VGs on any twin. They’re a simple mod that really works, in our opinion.

LOADING

As you might expect, the Duke is not a six-person airplane with full fuel, but it still beats anything in its class in terms of useful load and range. Late-model Dukes generally have a useful load of better than 2000 pounds, even when carrying full equipment. Earlier models, which tend to have less equipment and weigh several hundred pounds less, do even better: Some straight 60 and A60 models have useful loads approaching 2300 pounds. Such figures compare favorably with the cabin-class Cessna 421, which has seven seats to fill compared to the Duke’s six.

One drawback is the Duke’s healthy rate of fuel consumption, which translates into a smaller payload. Compared to other pressurized twins, the Duke uses a few hundred more pounds of fuel on a long trip. Still, the Duke shines in one respect: It can carry full fuel and two to four people. But there are variations in load-carrying capabilities.

One corporate owner of a lavishly equipped Duke reports that he makes three-hour, 600-mile trips with six people and 136 gallons of fuel. In contrast, a private owner, whose Duke has optional fuel tanks, says he’s at gross with full fuel, 100 pounds of baggage and two people.

The Duke’s single baggage compartment is located in the nose and can carry up to 500 pounds. According to one owner, this makes it easy to get the Duke out of its forward CG limits but difficult to get out of its aft limits. Another says he finds the airplane’s weight and balance characteristics benign—that is, hard to get out of CG in any manner.

COMFORT, HANDLING

Owners give the Duke decent marks for overall passenger comfort. Its cabin pressure differential is 4.7, so at 24,000 feet the Duke has a cabin altitude of 10,000 feet, which is superior to most six-seat pressurized twins. On the downside, the Duke is similar to Bonanzas and Barons in that it has a tapering cabin. Two adults in the back seats will travel elbow to elbow. In 1974, though, the B60 model’s side panels and ducting were reworked to offer a bit more lateral cabin room. More recent models come with redesigned seats that increase the amount of aisle space by a few inches. Of course, custom interior upgrades can provide far more space and comfort.

If you’re on the hefty side, it may be a tight squeeze entering the Duke’s cockpit. As for the cockpit layout, it’s user friendly: All the necessary controls, switches and avionics are within easy reach and view of the pilot, except for the circuit breakers. They’re a far reach on the far right of the copilot’s panel.

Cockpit visibility, though, is barely adequate. To see over the glareshield, a pilot of average height might be tempted to pull the seat forward; however, the seat will also automatically move up, which may put the pilot’s head next to the headliner.

We like that the power controls and gear and flap levers have been placed in the standard order (they’re reversed in earlier Barons). The flap system also is straightforward, with just three lever positions: up, approach and land. Maximum gear-extension speed is a phenomenal 175 knots. Also, dual control wheels are standard equipment, and the cowl flaps are electrically operated. A glance out the window will confirm whether they’re working.

Owners report the ride will be comfortable and fairly quiet, except during climbs or power settings above 2500 RPM. While most concur that the cabin is noisy at cruise and takeoff power, one owner reports the rear cabin seats are about as quiet as a King Air’s, but that the heater is inadequate in wintertime or at high altitudes, unless the cabin is filled with bodies.

In Beechcraft tradition, pilots compliment the Duke’s handling characteristics. Its controls have a solid (some say heavy) yet responsive feel, which is not surprising, since the Duke is the heaviest of all six-passenger airplanes. One owner, praising the Duke as a rock-solid IFR platform, said, “ILS and LPV approaches are like a railroad track.” Predictable and docile, the Duke trims up we’ll and holds its airspeed, and pitch changes are minimal when the flaps or gear are extended.

One pilot, though, said the Duke’s controls were too heavy for him, and that he prefers lighter and more responsive inputs. In turbulence, one pilot says the Duke is a “bear to fly” without a yaw damper, while another says adroit foot-work can be substituted for a yaw damper.

Even the lesser royals demand fealty. The Beech Duke is a sound example. Each subject, er, owner must render onto his or her lord absolute loyalty in the form of substantial skill with the sword, um, yoke, and the regular payment of massive sums of gold—or its equivalent—to maintain the royal house and feed its steeds. As our review of Beech Duke NTSB reports revealed, failure to faithfully do both is often punished harshly.

We dug through 40 years of NTSB reports looking for Duke accidents and found but 72. While the absolute numbers are low, only just under 600 Model 60 series airplanes were built, so nearly one- sixth of the fleet has been involved in a reportable accident.

The majority of the mishaps, 15, involved engine stoppages or fire due to maintenance that was too long deferred, done poorly (an unsecured fuel line chafing on an exhaust manifold, improperly torqued cylinders, loose fuel line fitting, to name a few) or nearly criminally wrong (automotive components in turbochargers, prohibited sealant between engine case halves). A thorough prebuy exam is essential, in our opinion, for any prospective Duke purchase.

As we read the maintenance-induced engine stoppage reports we found ourselves comparing what we were reading to what we found some years ago when looking at Cessna 411 accidents. Both the Duke and 411 are high-performance piston twins that are maintenance intensive, very expensive to operate and, as a result, can be purchased for less than other twins with less capability. Both suffered from a slew of maintenance-induced engine and system failures.

Our hypothesis is that a certain percentage of Duke owners get into the airplane because of an attractive price for the performance and then realize that they’re over their heads in cost and the inflight demands of the airplane.

That is consistent with the second most common Duke accident—there were 13 fuel-related events, mostly running the airplane out of gas after declining to buy fuel or buying “just enough” for a flight. One pilot bought fuel based on what he read on the totalizer. Once in the air, he stated that “the fuel mixture control was frozen” and he couldn’t lean the mixture (singular in the report). Rather than return, he pressed on, ran the tanks dry and slid to a stop 7 miles from his destination.

Another Duke owner reported engine problems. He landed and sought maintenance. A shop dropped everything and started working on his airplane. He got impatient, told them to stop, put in some fuel and departed. He ran the tanks dry—something he had done once before in that airplane.

Lack of willingness to pay for training seemed to be reflected in many of the engine stoppage accidents as few of the pilots feathered the prop on the dead engine(s). A number of those pilots then either Vmc-rolled the airplane into the ground or stalled in the traffic pattern if they got near an airport.

Five pilots overshot after landing we’ll down a runway or in a tailwind. Another four tore up their airplanes because the brakes were worn beyond limits and couldn’t stop the airplane.

Five pilots lost control in IMC, a number we’ll above what we expect to see in an airplane of this capability. One spun and recovered and, after landing, found that the airframe had been overstressed.

Two pilots attempted takeoff with the control lock installed; neither succeeded.

On rollout, a Duke pilot realized the nosegear was slowly collapsing. He tried to rectify the situation by cycling the landing gear switch. It only made things worse.

FEEDING IT

It should be no surprise that pressurized twins with amenities such as air conditioning typically cost a small fortune to maintain, but the Duke seems to be in a class of its own. Over the years we’ve heard Duke owners complain about mechanics automatically jacking up their prices for a Duke because it’s a Beechcraft at the top of the food chain.

While maintenance shops won’t feel sorry for you when you roll up to the hangar in a Duke, most satisfied owners correctly point out that the key to keeping bills down, and ensuring that the Duke’s engines reach TBO, is to properly operate and maintain the airplane. And woe to those who got a “good buy” on a used Duke that was not properly operated or maintained. It can be an expensive mistake.

To help reduce such costs, though, many owners stress that it’s important to find a shop that is familiar with the Duke, rather than letting a mechanic who has never worked on the airplane learn at your expense.

The Duke Flyers Association, which was formed in 1988, can help in this area. On a brighter side, buyers will be glad to know that parts availability has not been a problem.

Don’t even consider a pre-1976 Duke unless you’re sure its 380-HP Lycoming TIO-541 engines have received the appropriate upkeep. A pair costs some $110,000 to overhaul, which underscores the need for prudence in this area. As for other engine problems, here are some major ones that we’ve identified through owner complaints and service reports over the years:

• Cylinders and pistons. Until 1974, the TBO of the TIO-541 was only 1200 hours, primarily because of cylinder woes, with cracking around the exhaust ports the major problem. Since then, engines built or overhauled with improved pistons and cylinders have had a TBO of 1600 hours. One factor in cylinder failures was improper pilot technique in warming up and cooling down the engines; if temperature changes were too abrupt, cylinder stress would result. (Incidentally, a check of SDRs revealed numerous cylinder problems.) Still, Dukes built in 1976 and later (serial number 804 and up) have the upgraded engines. They have a 1600-hour TBO, and owners report operating them for 1600 and even 2000 hours.

• Turbochargers. The 60, A60 and 1974 B60 models had cast-iron turbo housings that tended to crack from the heat. This was no small problem in flight, since a turbocharger failure in a pressurized airplane can lead to partial or total cabin depressurization. However, the cracking problems stopped in 1974, when stainless steel blowers were fitted. By now, almost all cast-iron turbo housings have been replaced with the stainless steel ones; however, a few old ones remain, so be sure you’re not getting one of them—especially when sourcing the airplane outside of the U.S. If you are, make sure you get a price reduction.

During a demonstration ride, be sure to check for manifold pressure drift. Mixture control cables also have had their share of problems. Be sure to see that you’re getting the upgraded versions, since replacing mixture control cables costs several thousand dollars. Put a close eye on autopilot performance, too.

• Crankcases. Through 1977, Dukes had a high incidence of crankcase cracks (which goes to show, at least, that Continental isn’t the only company to have crankcase cracking problems). The Duke’s crankcases were beefed up in 1988, starting with engine serial number 78.

SERVICE ITEMS

Dukes came with jet-style nickel cadmium (nicad) batteries. You’d think that this would give a high degree of dependability and wear. But the battery is improperly cooled, and it can be destroyed by a slight improper adjustment of the voltage regulator. Average life is just two years or less. That may seem like a decent enough battery life, but not when the battery costs thousands. Fortunately, later model Dukes have lead-acid batteries. Beech has stopped offering lead-acid conversion kits, but you could probably have a Beech dealer install one. Our suggestion is that you try and buy a Duke with lead-acid batteries.

The Duke’s heated windshield drew various complaints: delamination and static discharges that pitted the plastic. We’ve heard of delamination problems on earlier Dukes but not later models. Some speculate that St. Elmo’s fire might be caused by not having the static discharge lines attached to the ailerons. (Incidentally, we didn’t find any SDRs pertaining to windshields.)

Other reports point to various problems with the exhaust. The Model 60, in particular, had short exhaust stacks that lead to flap corrosion. The condition of the exhaust pipes also should be checked at the rear by the slip joints; they came off and triggered a fire in one case.

Various magneto, landing gear, drive train and wheel problems also were mentioned in SDRs and owners’ reports, so make sure these items receive a thorough going over on a prepurchase inspection.

After receiving two reports of partial outboard elevator separations in Dukes, Beech issued mandatory service bulletins in 1989 to check the airplanes’ horizontal stabilizers and elevator hinge attachment areas. The bulletin affects certain Duke 60, A60 and B60 series models. Beech said an inspection should take two techs 12 hours to perform. Inspections were to be performed as soon as possible, but no later than the next 50 hours.

The Duke is subject to relatively few ADs, considering the complexity of the aircraft. The various spar cracking ADs that have affected Bonanzas and Barons in recent years don’t apply to the Duke, fortunately. Aside from various shotgun ADs, the only really important ones in the past 20-odd years have been 85-22-5, which dealt with Inconel bolts in the wing attach fittings, and 80-4-7, which called for inspections of the wing outer attach fittings.

CURRENT MARKET

When searching the market you’ll find the Rocket Engineering Royal Turbine mod, which is a B60 converted with two PT6A-35 engines rated at 525 HP each. Max cruise is 290 knots at FL270. With a 45-minute reserve up high, range is about 1000 miles and endurance about 3.5 hours. Gross weight is 7050 pounds, max landing weight is 6775 pounds and the published empty weight is 4650 pounds. With a total of 260 gallons aboard, 658 pounds can be carried in the cabin.

In late 2022, we found prices for Dukes all over the board. While a well-cared-for late-model piston Duke with low-time engines might sell for around $250,000, we spotted a couple of turbine Dukes in the $1 million range. There aren’t many conversions out there—under 25 as far as we know. We found a 1968 Duke that sold for $95,000. It had mostly original avionics and engines (300 hours total time) that were overhauled in the late 1980s.

There are plenty (200-plus) of “Grand Dukes” modded with BLR Aerospace (www.blraerospace.com) winglets and over 160 with aft body strakes. The company also has a VG kit—a popular mod for the Duke. The winglets are compatible with aircraft serial numbers P-247 and on. The early 60 and A60 models have different tips that aren’t compatible.

The VG kit is $3950 and install time is eight hours. Aft body strakes are $5750 and take 16 hours (plus paint work) to install. The winglets are $17,950, plus 30 hours of instalation for dry tips and 40 hours for wet tips. BLR’s Nick Dean said all Dukes up to serial number P-364 were 202-gallon aircraft; P-365 and on are all 232-gallon Dukes, although you will find a few earlier ones that were either retrofitted with the later Beech wet tips or that have an STC that BLR did for wet tips. The company made 30 ship sets of these back in the 1990s and sold all of them.

A Grand Duke fully modded has lower stall speeds—78 knots compared to 82 knots on a stock airplane in the clean configuration, and 70 knots compared to 76 knots on a stock airplane in the dirty configuration. The short-field approach speed is drastically lowered to 77 knots with a BLR-modded Duke, compared to 99 knots for a stock airplane, according to BLR. You’ll see better climb, too, when equipped—nearly 350 FPM better when both engines are making best power. The new gross takeoff weight of a fully equipped Grand Duke is 7000 pounds, compared to 6775 on a stock airplane.

To help with slam-dunk descents while still being kind to those finicky Lycoming engines, PowerPac Spoilers (www.powerpacspoilers.com) offers aftermarket “jet type” hydraulic spoiler kits for the Duke. The kit is around $8000 and the idea is to deploy them at any speed (up to Vne) for rapid descent rates without the need to pull the power off.

WHAT OWNERS SAY

While I am sure that every Duke is special to its owner, mine was the official 50th Anniversary edition: N850YR (“50YR” for 50th anniversary). A total of 596 Dukes were built so mine (serial number P581) was in the last batch.

This magnificent airplane had quite the adventure and was featured in the February 1983 AOPA Pilot magazine. Over time, winglets were added and then the plane took off for Germany where it became the show airplane for Beechcraft Germany. The call sign was changed and it flew in Europe for a while. Eventually it came back to the United States and was restored to its original N850YR tail number.

The Grand Duke conversion was completed by adding the aft body strakes and the BLR vortex generators, giving the airplane a new operational weight of 7039 pounds, 190 pounds of additional useful load, a 350 FPM increase in climb rate and significantly lower approach speeds.

I purchased the aircraft in 2019—37 years after it rolled off the line—and it became a passion project, stripped to its original airframe when the renovations and restorations started. Gone was the Miami Vice foam green interior and all the analog avionics. The renovation took nearly two years and produced an aircraft as modern as anything flying today, but maintaining all the original characteristics of the Duke B60, plus a brand-new leather interior.

It has a Garmin GWX 75 Doppler weather radar, dual Garmin GTN 750 navigators, a Garmin TXi EIS engine monitoring systems, dual Garmin 600 TXi 10.6-inch electronic displays, L3 standby instrument, PowerPac spoilers/speedbrakes, a new air conditioning system, the generators were replaced with alternators and the starters were replaced with high-torque SkyTec Aero E-Drive KPS starters. It also got a new pressurization system. It’s basically a super-plane now!

– Nick VandenBrekel – via email

After buying my first Duke in 2000 and getting involved with the Duke Flyers Association (www.dukeflyers.org, 419-755-1223 or 419-529-3822), I quickly learned that the largest disparity to Duke ownership is the ability to find a qualified shop to maintain it. So in 2001 Royal Air started an aircraft maintenance operation that centered around Duke maintenance to provide maintenance for our Part 135 charter operation. A few years later we opened our doors to the public. I know of hundreds of longtime Duke owners who will tell you wonderful things about their experiences (if asked). Unfortunately there are quite a number of unhappy Duke owners who gladly tell anyone and everyone who will listen about their negative experiences.

The tragedy comes in when you understand that it is not the aircraft’s fault so much as it is pilot error, in that a good aircraft becomes a bad aircraft when it is neglected, mistreated or owned by someone who really can’t afford the plane. Eventually this becomes a problem aircraft only to get sold under market price to someone who did not know what he was getting into. As a result, this problem Duke keeps getting passed around from person to person with stories abounding from the bad experiences.

I liken the Duke to a vintage Porsche. To fly one is like trading in your Buick for a sporty hot rod. A vintage Porsche should be maintained by a seasoned Porsche mechanic, but is truly a joy to own and drive if it is within your budget. A problem Porsche offered at an attractive price does no service to the unsuspecting buyer who always wanted to own one but never thought he could afford to buy one. The takeaway is to do your homework, buy a good Duke and steer clear of the “bargains.” The Duke Flyers Association is a great resource to anyone looking to learn more about this aircraft.

I have heard many nightmare stories, but I have also owned and flown one specific Duke for 15 years. It was literally one of the most reliable Dukes I have ever owned. I attribute this to buying a good one and flying the plane regularly and correctly. We have many customers who will tell a similar story about their experiences. The typical Duke flies an average of only 40 hours per year (that’s an average of once per month). That makes it hard to keep “sit-itis” from taking its toll. The planes that we see that are in the best shape are the ones that are flown regularly and log more than 150 hours per year.

Beechcraft chose to make Duke tails out of magnesium to save weight. Over the years it has become obvious that aluminum would have been a better choice. If not treated correctly by the paint shop, filiform corrosion will start, in time requiring an eventual repaint of the tail. On average, we see from five to 15 years for this corrosion to germinate and surface. It is a slow-moving corrosion and would only render the tail unrepairable if allowed to expand untreated for many years.

Throughout my flying career I have flown several Beech products up to and including the King Air 200, which is an excellent choice if your budget permits. But after years of flying both the King Air and the Duke I can still say without any doubt that nothing can touch the Duke dollar-for-dollar or pound-for-pound in the overall value of what you get for your money. That’s why I fly Dukes. You can contact us at www.royalairinc.com for advice about owning this awesome aircraft.

– Glenn Adams – via email