We’ve always put the Beech Musketeer, Sundowner and Sport in the affordable flyer category because, when cared for properly, they’re easy to own and easy to like.

They have signature Beechcraft build quality, which is sturdy on the ground and in the air, plus they have fairly roomy passenger-friendly cabins. Unlike the Beech B24R Sierra retrac, the fixed-gear Beech 19/23 should be simpler to fly and less complex to maintain. But like any airplane, choosing one that’s been we’ll maintained is the key to happy ownership, while respecting its performance limitations is the key to safety.

MODEL HISTORY

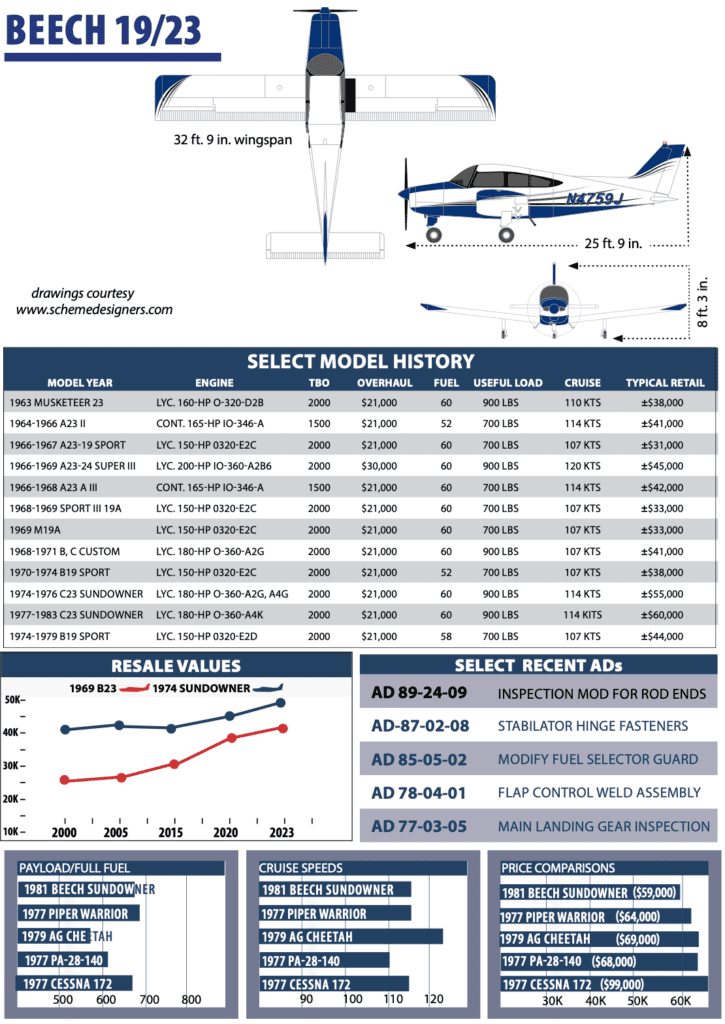

At this point, the earliest Model 23 birds are 60 years old. First appearing in the early 1960s, the Musketeer had a 160-HP Lycoming O-320 and could carry four people in comfort, as long as they weren’t in a hurry to get anywhere. The original Model 19 debuted in 1966. With just 150 HP, think of it as a two-seater with a backseat for more stuff. Except for the engines, the Sport and Musketeer are essentially identical. The original 1963 Model 23 had a 160-HP Lycoming, following the lead established by the Piper Cherokee two years before. But Beech soon re-engined the airframe with Continental’s IO-346-A—essentially an IO-520 with two fewer cylinders. The Super III Musketeer (from 1966) had a 200-HP Lycoming IO-360.

Beech switched engines again in 1968 to the 180-HP Lycoming O-360-A series, the motor that carried the line through the rest of its production life. But the model line can still be a source of confusion. Beech wheeled out the 150-HP Sport as a trainer in 1966, and by 1970, the two models had become the B19 Sport and the C23 Sundowner.

As for planes to choose from, consider that some 2400 Sundowners were built and many still fly today. The Sport isn’t quite so numerous, with only 900 built.

The Beech CT-134 was a military basic training derivative of the Musketeer built for the Canadian Armed Forces. It retired in 1992, and you might find a few light-aerobatic-capable Custom and Sport models. We spotted an aerobatic B19 Musketeer for sale listed at $40,000 with a high-time engine.

SPEED, LOADING, HANDLING

Up front, these airplanes are not speedsters or runway stars. The FAA determined in 1973 that when flying at its certificated maximum-gross weight of 2250 pounds, the B19 couldn’t even meet the certification climb-performance minimums. As a result, AD 73-25-04 was issued, limiting the B19’s gross weight to 2000 pounds, which hit performance hard. A Beech kit raised max gross back up to 2150 pounds, but the airplane was hardly a load hauler. After 1973, Sports that rolled out of the factory came with the mods already installed.

Owners take it in stride that cruise speeds in the 100-knot range are about the best they can expect from their 160-HP models. The Sundowner with the “big” Lycoming will do 117 knots with a light airframe and good rigging. Owners advise to check the flight control rigging for best speed and stability. The rudder/aileron interconnect makes for well-balanced handling, but if the plane doesn’t hold straight and level (with no rudder inputs) or if it doesn’t make book speeds, find someone with experience rigging these airframes.

Dan Dicker said his 200-HP Super III does 123 knots true at 6000 feet. “Four adults, bags and enough fuel for a four-hour flight is no problem.”

Owners also report gross-weight climbs in the 300- to 400-FPM range on hot days. Then again, this may vary by aircraft condition. One owner said climb rates of about 500 FPM through 9500 feet were possible. Loaded to gross, Beech claimed only a 792-FPM climb for the Sundowner at sea level.

The Sundowner is not a STOL ship in the landing department, either. Although the book says you can stop on less than 1000 feet of pavement at sea level with no wind, we say good luck. Allowing for real-world piloting skills, add at least 25 percent to that figure. With that margin and typically loaded, these airplanes may not be suitable for high-elevation airports or even sea-level airports with short runways.

And if you do manage to shoehorn your way into a 1000-foot strip, you’ll probably need a set of wrenches and a truck to get the airplane out. As we found in a recent scan of the NTSB reports, the accident pattern bears this out. If density altitude creeps up, you can find yourself needing jet-length runways. At a 2000-foot-high field on a calm, 88-degree day, figure on 1700 feet to get off the ground and almost 3000 feet to clear a 50-foot obstacle.

Consider that an NTSB study reaching back to the early 1970s identified the Sundowner as the worst aircraft in its class for hard landings. We’re talking about a rate of hard landings that was five times worse than the Cessna Skyhawk or the Piper Cherokee. Indeed, every time we’ve looked at the safety records of the Sport and Sundowner, the story has been the same—lots of hard landings and lots of overshot landings.

Landing too fast, says Sundowner owner John Becker, will cause you to float down the runway. “Nail the approach speed per the POH within a couple of knots, flare properly and the Musketeer can be greased in,” he told us. If you do drop it on hard, the trailing link landing gear might be forgiving. Still, gentle, mains-first touchdowns are the rule to prevent a crow-hopping excursion across the field. Beech went for stiff rubber shock mounts instead of oleos, converting what would have been wonderful cushioning into terrible springs, ready to help the aircraft rebound into the air. Precise speed control is the key.

“I used to own a 1964 Cherokee 180, and while the Cherokee landed much slower, that big Hershey bar wing picked up every bump in the sky, requiring you to slow down to Musketeer speeds,” owner Dan Nelson told us.

Many have found that carrying some power into the flare provides more controllability into the touchdown. Some owners tell us they carry ballast in the baggage compartment to offset this.

The airplanes have nice, wide-stance main landing gear, so once the aircraft are firmly on the ground, they handle and track quite well. “If I want to turn the plane on the ground, I hold one brake then throttle up to around 1400 RPM and spin it about with one wheel,” one owner said of his Sundowner.

FUELING THEM

In all but the early model Sports, standard fuel load is 57 gallons usable. That’s enough gas to carry the Sport about 620 miles, while the Sundowner will cover only 530 miles on the same load. That fuel load may sound impressive, especially when you look at the fuel capacities of the competition.

The Piper Cherokee, American General (Gulfstream/Grumman) Tiger and Cessna Cardinal all carry 7 gallons less gas. Yet, all those airplanes can fly just as far because their higher cruise speeds let them cover the same amount of ground on less fuel. Fill the cabin and you can’t fill the tanks, it’s that simple. The Sundowners can be expected to haul about 900 pounds of useful load in their average equipped condition. If you need full tanks, that means you can only carry three people and 50 pounds of baggage.

If you’re in a Sport, toss out the third person and the baggage and you still get to sweat those high-weight climb rates. So, the Sport/Sundowners are cheap to buy, but the payback is lack of performance; there’s still no free lunch.

Early Sundowners had about 3.5 gallons of unusable fuel in each tank. The fuel inlet was moved in the later models, reducing the unusable fuel to roughly 1.5 gallons in each tank.

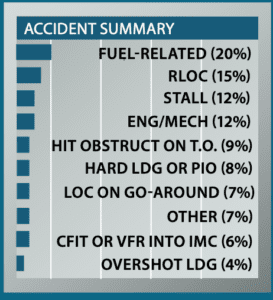

While our review of the 100 most recent Beech Musketeer accidents revealed that the most frequent single cause was fuel-related engine stoppages (20), the area of greatest exposure for a Model 19 or 23 pilot is during the landing sequence.

Thirty-four pilots bent their flying machines because they made a hard landing or the landing degenerated into pilot-induced-oscillation (PIO), lost control on the runway (RLOC), went off the end of the runway or had the things go badly enough on a landing that they decided to make a go-around (almost always a wise decision, in our opinion) but lost control during the go-around. Several of the LOC events on a go-around involved the pilot stalling the airplane, often during a high density altitude operation.

With the wide track main landing gear, we were a little surprised to see 15 RLOC events, an indication that there are many factors that make for good ground handling, something we don’t think the Musketeer line will ever be accused of having.

The Musketeer line is not particularly speedy, yet four pilots flew final so fast that they couldn’t land and get stopped on the available runway. One pilot was so fixated on landing rather than going around that he touched down with 200 feet remaining on a 3000-foot runway, proceeded rapidly off the end, through a fence, down a hill and came to a stop on a road. Another overshot a 4400-foot runway and didn’t stop until hitting a fence 340 feet off of the end.

The 20 fuel-related accidents mostly reflected that if a pilot has more than one fuel tank to choose from, he’s likely to mess up. Over half ran a tank dry and then didn’t change tanks or didn’t do so in time to get a restart. All but four of the others simply didn’t start the flight with enough fuel to finish it. Two didn’t check for water and contamination prior to flight, only discovering it during the post-

accident investigation following the engine going quiet.

One pilot placed the fuel selector between detents, restricting the flow of fuel to the engine and causing a loss of power. One pilot picked his airplane up from the annual and took off carrying a passenger. The engine quit at 50 feet. The fuel selector had been turned off during the annual and the pilot didn’t do a thorough preflight. That one confirmed our strong recommendation to do a careful preflight after any maintenance and make the first flight solo, in day VFR weather.

What got our undivided attention was the number of serious accidents involving a stall after takeoff while attempting to clear obstructions, hitting an obstruction after takeoff or a pilot realizing during takeoff that he couldn’t clear obstructions, aborting and rolling into those obstructions.

The accidents had a scary commonality—usually a high density altitude, a relatively short runway and an airplane loaded near gross weight. One example is a pilot who tried a takeoff from a 1250-foot runway with 30-foot trees, 50 feet off the end. He didn’t make it.

We urge great caution during high density altitude and/or short runway ops in a Musketeer. It is not a STOL machine.

OWNERSHIP EXPERIENCE

Our sense is that owner satisfaction is pretty good for the Beech 19/23 series because there just isn’t a lot to fix on a well-maintained airplane. Better yet, like most Beech products, they’re routinely described as being delightful to fly. In the air, the controls are light and we’ll harmonized, smooth and responsive. They’re stable enough to make good IFR trainers.

But don’t shortchange the prepurchase evaluation on any of the models. The landing gear, for example, should come in for detailed scrutiny as we’ll as during annual inspections. By the same token, make sure the firewall gets a good once-over, since bending and warpage of the firewall is a common consequence of excessive crow-hopping and nose-first arrivals.

Another item to scrutinize closely on annual inspections is the fuel caps. The NTSB called for pressure checks of older caps, but simple visual inspection should be able to detect caps that have become too stiff and crusty to provide a good seal to the wing filler port. Valve sticking, we’re told, on the O-320 and O-360 should be considered facts of life. Lycoming Service Bulletin 388B calls for checks of valve guide wear every 400 hours, but we’d cut that interval in half if you’re experiencing normal 50- to 100-hour-per-year utilization. Cut it in half again if you’re flying less than that. The inspection is simple, once you‘ve got the proper jigs, and it could save you thousands in later cylinder work.

In the just-plain-annoying category, there are complaints about leaking windshields and windows. This sort of thing is not really a problem limited to the 19/23 since most of the smaller GA singles seem to suffer from window leaks to one extent or another.

“My Sundowner has a Lycoming O-360-A4K engine and it’s virtually bulletproof. The only issues I’ve had are the usual wear and tear items (like replacing spark plugs every eight to 10 years), the exhaust pipe baffle needed repair, valve cover seals needed replacing—those kinds of things. My engine has about 850 hours since new. Most of it was put on since I’ve owned it,” John Becker told us.

In the current hard insurance market, the Beech 19/23 series should be easy for pilots of all ages because it isn’t a retrac and it’s relatively simple to fly. Still, plan on transition training from someone who understands how these airplanes perform on landing. Becker (age 69) said his insurance premium is $960 and he has 900 hours of total experience, with 700 hours in the Sundowner.

We scoured the market in summer 2023 and simply didn’t find many 19/23 models for sale. Those we did find were premium priced over Aircraft Bluebook’s typical retail pricing. A 1980 C23 Sundowner has a Bluebook retail of $58,000 and we found one with a recent avionics upgrade and new paint for $82,000. As usual, you’ll pay for improvements.

Reader Dan Dicker told us he paid $65,000 for his model Super III (with a high-quality overhauled engine) in 2021, pointing out it was far less than a Cessna 182 with a timed-out engine.

Unanimously, we’re told one thing that makes owning a Beech 19/23 easier (and the retrac Sierra, twin Duchess and two-place Skipper) is the Beech Aero Club (BAC). “The $50 a year membership gets you every scrap of knowledge that exists about these aircraft. Contact them at www.beechaeroclub.org.