Believe most of the things you’ve heard about the Aviat Husky backwoods taildragger. Yes, the Husky is just as good at sliding down GPS approaches at big-city fields as it is plopping down on a sandbar at your favorite adventure destination.

Unapologetically designed with the Super Cub firmly in mind, Aviat gets credit for marketing the airplane to a wide range of customers—from pilots new to taildraggers looking for a second or third airplane for play to pros who might use the airplane we’ll off the beaten path.

Utility is the name of the Husky’s game. Amphibious floats, snow skis, big tundra tires—you can do a lot with a Husky. That’s why it is no surprise that well-cared-for models still fetch top dollar in the current market, and you’ll pay a premium for mods, options and refurbs.

HUSKY HISTORY

Back in the day, the Part 23-certificated, well-built and good-performing Aviat Husky successfully competed against its forebears—including Piper’s Super Cub and offerings from Maule and American Champion. These days there is tighter competition, with good-performing models from CubCrafters and Legend Aircraft, to name two.

Flash back to the Christen days (which before making airplanes specialized in making accessories—inverted oil systems, fuel pumps and restraint systems—for aerobatic airplanes), which branched out into the homebuilt market with the Christen Eagle, a highly capable kit-built aerobatic biplane in the mold of the Pitts Special.

Then in 1982, Frank Christensen purchased the Pitts type certificates, along with the factory, effectively cornering the contemporary market for aerobatic biplanes. Thanks to better-performing monoplane designs from builders like Extra and Sukhoi, the Pitts/Eagle domination of aerobatic competition’s upper end is no more. But, the Pitts was star of the show for a time; it remains viable and continues in production. Recognizing the market for aerobatic airplanes is small, Christensen nonetheless had a factory, a workforce skilled in building tube-and-fabric airplanes and a family of solid, proven products. But, he needed a new product and saw opportunity in the bush market.

At the time, the only competitor being manufactured was the Maule and—despite that company’s seeming immunity to the ills plaguing the rest of the industry from time to time—precious few of them were rolling out the doors. After trying to buy rights to the Super Cub, the Champion line and the Interstate/Arctic Tern, Christensen reportedly considered the asking prices (including the assumption of product liability for previously produced airplanes) unrealistic.

The answer? Build an all-new airplane. Christensen and designer/engineer E. H. “Herb” Andersen Jr. determined they could develop and certify their own design at lower cost and in less time than buying and producing an existing product. So that’s what they did, bringing the initial A-1 Husky from conception to FAA certification in just 18 months.

Since the costs of development and certification have stopped many would-be aircraft manufacturers dead in their tracks, this tale says something about the company’s management. Equally revealing is the amazingly short time it took to bring the Husky to market. Even so, the Husky didn’t set the world on fire: Only 68 were produced the first year and an average of 30 to 40 annually since.

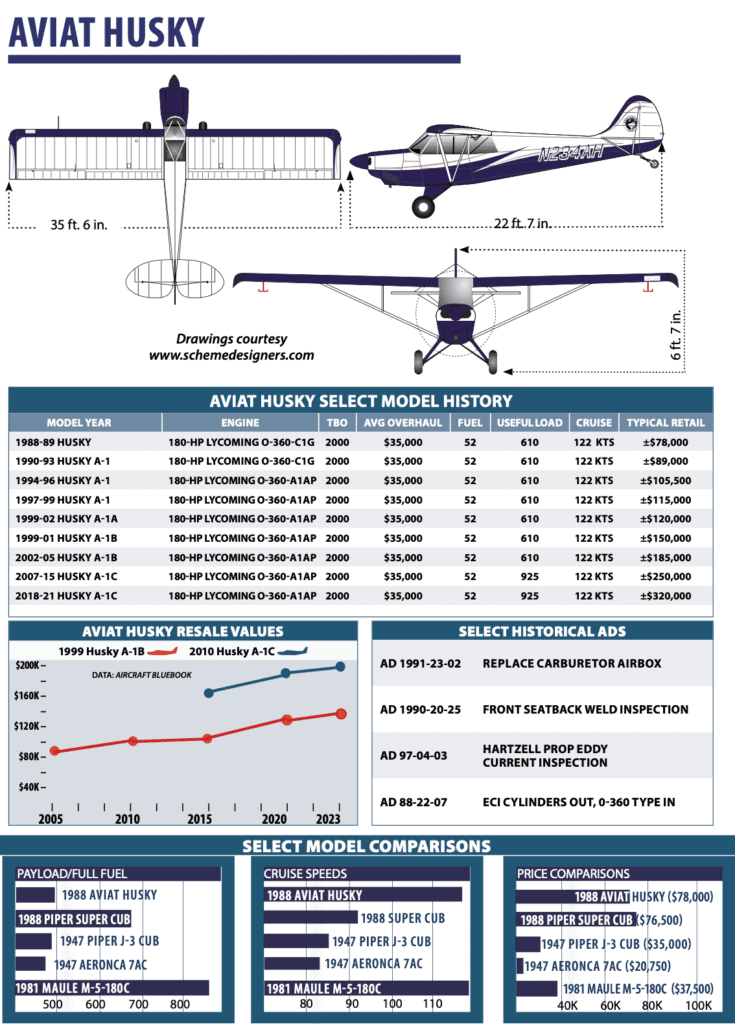

It was a short run for the first Huskys (1988 to 1989), replaced by the A-1A and A-1B in 1999. They were better. The Husky A-1A featured a 90-pound gross weight boost, to 1890 pounds, while the A-1B’s gross was 2000 pounds. To this point, all three models mounted a carbureted 180-HP Lycoming O-360 engine, turning a Hartzell constant-speed prop. That’s in contrast to an unmodified Super Cub, with its 150- HP engine and a fixed-pitch prop.

Both the A-1A and A-1B were produced until the 2002 model year, when the A-1A was discontinued. In 2007, Aviat obtained FAA certification of the A-1C Husky—a much better hauler—which has a 2200-pound gross weight, an increase of 200 pounds over the A-1B. Structural modifications included new landing gear, a five-leaf tail spring, a new wing with extended flaps and spadeless ailerons, plus a new wing-flap control handle.

Additionally, according to the FAA type certificate, the new model’s CG envelope was “reduced forward and expanded aft.” The A-1C comes with a choice of the standard 180-HP O-360 or a fuel-injected IO-360 Lycoming pumping out 200 HP—a lot of engine for this airframe. The A-1B was discontinued as of the 2008 model year, ushering in the current-production A-1C, priced around $375,000 in early 2023.

BUILT SIMPLE AND STRONG

When it comes to backwoods taildraggers, that’s a good recipe for success. Smartly, Christensen and Andersen kept a sharp focus on the Super Cub. The objectives included good short- and rough-field performance; ruggedness, accessibility and serviceability to simplify support in primitive conditions; outstanding slow-speed handling coupled with docile stall characteristics; good endurance and reasonable cruise capability.

You can’t argue that the Husky taildragger looks a lot like a Super Cub. We don’t think that’s a bad thing: The Super Cub has remained popular for a long time and for good reason. The Husky’s fuselage is welded 4130 chrome/moly tubular steel with a full-depth aft fuselage for greater strength. Aviat got the engine combination right, too. Except for the A-1C-200, the aircraft is powered by either a Lycoming O-360-C1G (early models) or an O-360-A1AP (1994 and later models). This Lycoming is widely acknowledged to be almost indestructible. The engine cowling and forward fuselage are skinned with aluminum. The aft fuselage and flying surfaces are covered with polyester; the seams are taped with cotton and fastened to the structure by oversized pop rivets.

One clear advantage newer-airplane designers have is the ability to examine similar designs and correct any shortcomings cropping up over time. For example, rather than the problematic wood spars Champion used, the Husky’s wings employ dual aluminum spars and aluminum ribs. They are supported by fore and aft struts, which were designed to eliminate corrosion and other problems encountered over the years in a large number of strut-braced airplanes, including certain Piper and Taylorcraft models, for example.

For easier maintenance, a Husky’s nose bowl is split—allowing for removal without touching the propeller; the cowl has large doors on either side for easy engine compartment access (good for preflights). Moving aft, the fuselage is metal-clad to the end of the cabin and features several removable panels. The aft fuselage, which includes the battery bay, is accessible through a large panel on the port side. (A baggage door was optional.)

The landing gear is conventional in more ways than one: It uses reliable, proven bungees for shock absorption, and mounts them inside the fuselage to reduce drag. The brakes are good and the track is wide, which helps ground handling. Tundra tires are a popular add-on, making soft-field and rough-country operations much simpler.

For other terrain, all A-1s are built with float attach fittings installed. The only additions required for straight or amphibious float operations are lifting rings and a ventral fin. For the same reason, dual-puck brakes—required for the tundra tires—are standard on all aircraft. These brakes are quite good and offer plenty of stopping power. Meanwhile, the Husky is approved for both retractable and wheel-replacement skis, as we’ll as for banner or glider tow hook installation.

Changes made to the line since the first A-1 rolled out the door have been incremental improvements, largely as a result of real-life service experience. To its credit, Aviat has designed all improvements to be field-retrofittable to existing airplanes.

Since early models can be updated with the later improvements, there is no better or worse model year. As a result, one of the keys for any prospective buyer is ensuring all desired mods and any mandated changes have been performed, and to be careful of overall condition.

IT CAN DO WHAT?

Several years ago Aviat ran a sell-ad that boasted of the Husky’s 200-foot capability. We’ve flown enough Huskys to be skeptical, so we flew a newer one and found that unless the airplane is stripped to minimum weight and flown by an expert, the claimed 200-foot takeoff distance is a stretch, especially on unpaved surfaces at higher elevations.

The AFM for the Husky provides a chart to calculate takeoff distances for the airplane at gross weight in calm wind conditions. For a 2200-pound gross weight A-1B, at sea level on a standard day, the ground roll portion of the takeoff distance for a normal takeoff—flaps up—is 775 feet. For a maximum performance takeoff—30 degrees of flaps—the ground roll drops to 580 feet on a dry, paved surface. At a high elevation airport (5000 feet), we found that a max performance takeoff is 800 feet. At the time, Aviat told us that’s for an average pilot using standard technique, and the figures have a built-in safety margin for reliability. After flying a loaded Husky and doing numerous takeoffs, we found the performance consistent with the AFM data, but still shake our heads at why Aviat ran an ad contradicting its own published data.

The Husky (and for that matter, the Scout and Maule) have very high adverse aileron yaw when maneuvering at low speed. A cross-control stall in those airplanes can mean a loss of several hundred feet even if the recovery is done precisely right. The Husky’s trim system requires a new pilot to spend a little time getting used to its operation and how to recover from an out-of-trim event, like during a botched landing into a go-around.

The best recovery technique for bounced, poorly aligned or otherwise botched approaches, at least initially, is to add power and go around. The Husky will bounce mightily and can easily get sideways—not a good way to re-contact the ground. With full power, the airplane leaps back into the air; with just a touch, it still flies.

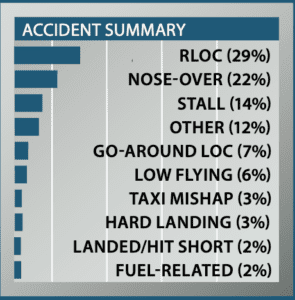

Our review of the 100 most recent Aviat Husky accidents was notable for not only what we saw—lots of landing- and maneuvering-related accidents—as we’ll as what we didn’t see—almost no engine failure, fuel-related or VFR into IMC crashes.

We’ll start with the good stuff. There were but two fuel-related accidents—well below the 5 to 20 percent range we observe in most types of aircraft—and one was due to the pilot not firmly attaching a fuel cap. Our operating hypothesis for this nearly unmatched low rate is a combination of a dirt simple system and a fuel capacity that means the airplane’s endurance exceeds the bladder endurance of most pilots.

The engine failure rate was also a tiny 2 percent. We usually see a rate on the order of 20 percent, often due to poor maintenance. We aren’t going to guess why the Husky series has such a low rate of engine stoppages due to mechanical issues, but for an airplane that regularly goes into the backcountry, we like it.

We were also interested to note that there were no VFR into IMC accidents. We can’t recall the last time we observed that in any aircraft type. We like that a lot as well.

Enough with the sweetness and light. Husky pilots may show good judgment when it comes to weather, but they sure seem to have trouble when it comes to the stick and rudder end of things—landing and maneuvering. From runway loss of control (RLOC) events (all but one on landing), through nosing over on landing, plus hard landings, LOC on a go-around after having things go south on landing and touching down short of the runway, there were 63 landing-related accidents. That’s just three fewer than our all-time leader in the landing hit parade, the Cessna 195.

We’ve previously noted our concern with the high degree of adverse aileron yaw during slow flight in the Husky. That means the pilot has to be fully in the game when slow, and know what those pedals on the floor are for. We’ve seen too many owners of high-performance airplanes buy a Husky as a toy and either wreck it on landing or scare themselves enough that they sell it within several months of the purchase. It’s not a toy—it’s a seriously capable STOL airplane that requires a serious checkout and recurrent training.

The Husky has the highest rate of nose-over accidents we’ve seen—usually due to over-braking. (Some of the RLOC accidents also ended up with the airplane on its back.) The gear geometry means keeping the stick back and being gentle with the brakes—another part of a good checkout.

Even though there’s a lot of power, 14 percent of Husky accidents involved stalling, usually on takeoff or after a go-around. That’s a bunch. The airplane may feel like it will climb vertically. . .

And, there’s judgment when it comes to strip selection. One owner made two go-arounds before landing. Almost immediately he realized that he couldn’t get stopped so he went around. He cleared the trees, but then stalled and went in. Turns out that he’d mistaken a 650-foot long RC model aircraft strip for his destination airport.

WING AND FLAPS

The Husky’s non-tapered wing comes with Fowler-type, slotted flaps hinged to move aft as they are deployed. Even at full—30 degree—deflection, they provide more lift than drag, making for good short-field performance. Elsewhere on the wing, attention has been paid to the ailerons, as well. They are symmetrical in section, and the leading edge has a larger radius than the wing trailing edge it abuts to maintain attached airflow during low-speed and high angle of attack flight.

Counterbalanced aerodynamic spades hang from the bottom of the aileron leading edge on models through the A-1B; they were eliminated on the A-1C. Borrowed directly from the four-aileron Pitts, the design permits full roll authority we’ll into the stall.

Of course, any airplane designed for utilitarian purposes should be a straightforward, forgiving airplane to fly. Although we think the Husky demands extra effort to extract all its performance, the Husky meets these objectives by all accounts. Thanks to the good aileron and rudder authority, combined with the Fowler flaps, the pilot really has to provoke the Husky to get it to bite.

Saying that, spins are virtually impossible to get into with flaps deployed. But, when flaps are retracted, it will reward uncoordinated control input with a snap over the top in power-on stalls. It won’t spin, but the resulting spiral or corkscrew maneuver can be attention getting. During cruise in turbulent air, speed control is important at most altitudes, since indicated airspeed is fairly close to the Vno of 103 knots indicated—Vne is 132 knots. Wing loading is light at 9.8 pounds per square foot, so the ride in turbulence won’t be pleasant.

On the brief takeoff run, even at high density altitude, liftoff speed is reached quickly and the effective brakes help make short stops easier. The best technique for ensuring the airplane will stay on the ground is to retract the flaps during the short landing roll. The Husky wants to fly.

Max-performance takeoffs result in continuous climb and there is no sagging-off even while flaps are retracted. It is a credit to the airplane that, once a pilot is familiar with it, such performance does not require superior technique—it’s natural.

No-flap takeoffs require more ground run, naturally, but taking off in the three-point attitude produces a short run and healthy climbout (1500 FPM at sea level at the best rate of climb speed of 63 knots).

HUSKY HANDLING

Handling is typical for this class of airplane: It likes lots of rudder input, and it’s not overly twitchy. Transitioning pilots are at risk of groundloops until they have some taildragger experience. Control harmony is fairly good, which is sadly uncommon in other backwoods taildraggers.

Rudder and aileron forces are linear in relation to airspeed. Because of the bungee trim system, elevator deflection forces are fairly high, even at low speed. In fact, we think it trims like a heavy airplane—a little bit at a time and almost always in response to any power or attitude change. Rudder authority is good right down through low-speed flight, and the aileron spades work to maintain control at low speeds.

For a lightly wing-loaded airplane, the Husky is quite well-mannered in cruise. Properly trimmed, it does not require a lot of attention to maintain course. This makes it a better instrument platform than many of its peers and some owners fly Huskys in IMC. We’ve done it, including precision GPS approaches, and trimmed up, the Husky tracks the glideslope like it’s on rails.

The big virtue of the Husky is that even during slow flight, properly configured, the attitude of the aircraft is flat; it is flying on the wing rather than hanging on the prop.

This is a big safety advantage for spotting, patrol and other low-altitude, low-speed operations, since at these speeds the Husky is not flying on the edge of a stall and the airplane very largely takes care of itself.

Remember—this is a backwoods taildragger—and we’ve all seen the videos of highly skilled backwoods pilots doing impressive things with their Huskys in remote settings.

Still, a Husky works at busy airports with a mix of traffic. Recommended approach speeds are very low (52 knots), which would give your typical Boston controller fits. But it can be flown at an indicated 100 knots right to the threshold and slowed easily to proper touchdown speed. Bring your A game.

Tailwheel steering authority on the Husky is good, which makes ground handling simple except in high winds. A touch of differential brake swings the aircraft around briskly. The brakes are powerful: At slow taxi speeds, their overenthusiastic application will bring the tail off the ground.

Pulling the airplane around on the ground is aided by convenient handles on both the aft fuselage and elevator. Demonstrate this to the line personnel when transiting.

NOT A COMFY SPEEDSTER

But what’s the hurry? Cruising at 55 percent power should yield 113 knots true; at 75 percent, 121 knots. Top speed at sea level is 126 knots. Even float-equipped cruise at 5000 feet is quite respectable at around 106 knots.

Book numbers for fuel consumption at 55 percent is 7.7 GPH; at 75 percent it is 9.3 GPH. Still-air range at 55 percent is 695 miles. With power set for an airspeed of 96 knots indicated, endurance is an impressive seven hours.

When loading for a trip, CG is rarely an issue, since the bias is toward the front end of the range with just one aboard due to the relatively large engine and constant-speed prop. Standard useful load is 610 pounds. A full load of fuel—50 gallons usable, or 300 pounds—leaves 310 pounds of payload available.

The baggage compartment behind the rear seat—reached by folding the rear seatback forward—is rated at 50 pounds. An access door is a factory option on newer aircraft. Keep fit and flexible for flying a Husky—getting in and out of one is hard to do elegantly. Rather than sliding in like in a car, the pilot and passenger more or less hoist themselves aboard—Cub style.

Once seated, forward visibility is very good for pilots of average-to-tall height, despite the large, high wing (shorter pilots can adjust the view by using thicker seat cushions). A skylight in the overhead helps spotting traffic in turns. One of the biggest shortcomings of the Husky, at least for tall pilots, is the front seat. It is a fixed part of the structure. All adjustments are made by changing cushions.

It may be more comfortable in the aft seat. The seat is wider, the angle of the backrest is better and there is more legroom fore and aft. But back-seaters won’t get much cabin heat—not an issue in warmer climates, but certainly one to consider in colder ones. With relatively little soundproofing the noise level is high. Bring good ANR headsets.

WRENCHING IT

There haven’t been too many squawks on the airplane, but it would be a good idea to check the stainless steel control cables for wear and look for any vibration-related problems in the baffles and cowling that might be related to the relatively rigid engine mounting. It’s a pretty simple airframe and that generally means easier annual inspections. Plus, treat the Lycoming powerplant right and you should be rewarded with relatively benign maintenance costs, compared to say, a Bonanza. As for FAA ADs, check them during prebuy; AD 90-20-5 applies to 1988 to 1990 models and calls for inspection of welds on the seatback and addition of reinforcements if needed. The other AD, 91-23-2, applies only to 1988 models and calls for the replacement of the carburetor air box. AD 97-04-03 is on the Hartzell prop and requires eddy current inspection.

One source for help with ownership and shopping for a Husky is the www.flyhusky.com forum. There is a Husky Facebook group with roughly 3000 members.

REAL-WORLD OWNERSHIP

As with any taildragger, get an insurance quote before making a deal on a Husky. Senior pilots (north of 70) might pay higher premiums and the same might be true for low-time first-time taildragger pilots. For others, it’s not so bad.

“I’ve been happy with insurance, currently paying $2403 for a $250,000 hull value and two high-time pilots, albeit one with under 100 hours of tailwheel time,” Kent Wein told us. Like others, he’s generally pleased with supportability, although it doesn’t come without expense. “It’s nice to call Aviat and get pretty much any part I need,” he told us. On the other hand, a service bulletin on 100 airplanes for replacement of fuel vents totaling $1100 was a source of frustration. A cracked exhaust at 200 hours total time pushed him (and several other owners with premature failure) into buying a Power Flow aftermarket exhaust. “It seems to produce a bit more power and appears more robust, and certainly puts out a ton of cabin heat—a big improvement over the stock exhaust,” Wein said.

But others don’t hang on to their Huskys for long, and we’ve often wondered why there are generally a decent selection of low-time models to choose from. We’ve known more than one owner who thought they wanted one, that is until they started flying one and realized just maybe it was a bit too much taildragger for their skill.

In March 2023 we found a variety of Huskys on the current market, including a handful of late-model birds for sale by Aviat. One VFR A-1C-180 model with 70 hours on its clock was listed at $453,139. It had big tundra tires, a Garmin portable GPS mounted in the panel, big-screen engine display, a sharp “Beartooth” paint scheme, vortex generators and a Hartzell composite prop.

McCreery Aviation in Texas had a few good Huskys, including a 2012 VFR-equipped big-engine A-1C-200 with only 460 hours total priced at $299,000. You’ll pay a hefty premium for IFR machines upgraded with Garmin WAAS navigators, primary flight displays and autopilots. Want floats? It’s a good platform.

We found an IFR-equipped 2014 A-1C-180 with only 260 hours on Wipaire amphib floats. It had a three-blade propeller, big-screen Garmin avionics and a nice paint job for $359,000.

For something closer to lower budgets, there was a 1996 Husky A-1 with 2050 hours total time and 840 hours on the engine since a major overhaul. Upgraded with a Dynon SkyView HDX avionics suite with autopilot, the airplane was listed for $119,250.

Does the Husky make for a good first taildragger? For newbs who respect its power, set high minimums for ops in tricky terrain and commit to real training, we think it does.