In the days before even modest sedans had six airbags, vehicle sniffing radar and kiddie seats that could double as nuclear containment devices, car guy Lee Iacocca once famously said safety doesnt sell, style does. Four decades later, in the airplane realm, safety apparently does sell, given the success of Cirrus with its full-airplane parachute system. Field Morey Unfortunately, the BRS system doesnt apply to many of the 160,000 or so legacy airplanes that constitute the real world of general aviation for most of us. That means we are left to our own devices to do what we can to improve the safety of older airplanes. The word “safety” itself is maddeningly ambiguous, but for this article were defining it in two ways: enhanced wherewithal to avoid accidents in the first place and improved likelihood of survival in the event that an accident occurs anyway. In a typical year, we examine dozens of products, some of which purport to be safety enhancers-terrain avoidance gear, traffic nags, weatherlink equipment and the like-all great gadgets. Some owners buy these products simply because they want them and thats good enough. If aviation-related purchases had to be rational, how many of us would own airplanes in the first place? But on the slim chance that there’s a place for the voice of reason and assuming that you have only so many dollars to spend on aircraft upgrades, what safety-related purchases give the most value for the least amount of money? Thats the question we’ll attempt to answer here. Moreover, were arranging these in order of priority.

Are You Normal?

Each of us was born with-or we develop-our own herd of personal demons. Some pilots sweat bullets at the mere thought of actual IMC while others fear the bolt-from-the-blue mechanical failure. Thats another way of saying we tend to inflate the risk of things that scare us while discounting things that don’t, thus we sometimes protect ourselves expensively against small risks while ignoring larger ones.

The only rational way of judging risk in aviation (or anything else) is to look at hard numbers-overall accident totals and accident rates. Some categories loom large-landing and takeoff accidents, VFR into IMC, fuel exhaustion-while others rank low enough to be all but flukes, such as pilot incapacitation or even mid-air collisions. The best snapshot view of the accident big picture is found in AOPA Air Safety Foundations Nall Report, which you can download from AOPAs Web site. The Nall report is a no-nonsense summary of accident causes thats as good a source as any of data by which to make risk assessments. Although its conclusions apply to the pilot world at large, the Nall report does beg this question for anyone who reads it: How do I fit in? Am I typical of the pilot population at large or do I have more or less risk in some areas of flight operations?

Were utterly unable to answer this, but our view is that the pilot population is probably more homogenous than most of us would admit. In other words, if you think youre too smart to be susceptible to a fuel exhaustion accident-a big percentage of total accidents-you may be kidding yourself.Herewith are our views on the best safety enhancing investments.

Number 1

An Instrument Rating

The Nall report grimly notes that 75 percent of all GA accidents are due to pilot error and more than 80 percent of fatals are due to pilot mistakes or misjudgments. These are lack-of-proficiency accidents that can, one way or another, be traced to lack of or poor training or anemic proficiency due to limited flight activity. Either way, the results are the same.

In our view, ongoing training addresses this shortcoming across the board, improving flight skills from basic stick and rudder work to instrument scan to radio skills, all of which contribute to a less accident-prone pilot. Typically, an instrument rating costs $5000 to $7500, depending on the aircraft used and how much sim time is included. But in our view, no other single investment impacts proficiency and safety to the degree that adding an instrument rating does.

Number 2

A Real Flight Review

Or a real instrument proficiency check on a regular basis. Cost: under $500, including the airplane time. Were talking here about a challenging, skill-enhancing flight review or IPC from an instructor who gets the picture, not a pencil-whipped love fest that barely warms the engine oil. Do it on a gusty day with a crosswind and you may avoid being among the several hundred pilots a year who suffer runway loss-of-control embarrassments.

Number 3

Add a Rating

See numer 1. The accident record suggests that you cant be over-trained. Typically, a commercial rating improves stick-and-rudder skills for the sum total of about $1500, including the airplane time. If you already have an instrument rating and a commercial certificate, adding an ATP for under $1000 is chump change and sharpens instrument skills.

Number 4

Fuel Totalizer

Of all the stupid pilot tricks that pilots pull, one of the dumbest is not just running out of fuel but, as a group, doing it about twice a week, on average. This accounted for more than 100 accidents in 2005, according to the Nall numbers. We think there are multiple reasons for this, but our theory is that two stand out: Pilots don’t really know how much fuel theyre burning and they rely too heavily on inaccurate panel gauges.

To address this, we think a Shadon fuel totalizer-at about $2500 installed-is a positive step in the right direction. Front and center in the panel, it gives hard numbers on both fuel remaining in gallons and endurance and thus

forces engagement with the dynamics of your fuel state in a way that a watch doesnt. Its true that a totalizer is only as smart the pilot using it, but we think the safety balance favors having one rather than not.Number 5

Weatherlink

The Nall study finds that weather is a factor in 4.6 percent of all of the pilot-caused accidents, but 13.6 percent of the fatals. That amounts to about 50 accidents a year, 33 of them fatal.

Its not that weather reached out and smote the airplane; the pilot simply blundered into weather he couldnt handle. The overwhelming majority of weather-related accidents are VFR-into-IMC poor judgment calls but-and this significant- 9.1 percent are thunderstorm related. For the past five years, weve had the technology to avoid the thunderstorm threat strategically and tactically in inexpensive datalinked weather. Our first choice is Garmins GPSmap 396, which, at $2195, is capable, inexpensive and relatively foolproof. If you want more capability, spend more for the GPSmap 496 and get terrain avoidance thrown into the deal.

Why not a sferics device, which have been available for three decades? A fair question. But theyre more expensive, require installation and interpretation and they provide little strategic avoidance capability. Furthermore, weatherlink can also provide real-time METARs and forecasts, which further inform weather judgment calls.

Number 6

Progressive Maintenance

Yes, maintenance. More than 200 accidents a year-thats about 16 percent of the total-are due to mechanical or maintenance-related causes, although these tend to have a low lethality rate. About half are related to engine and propeller malfunctions of some kind. Its anyones guess how many of these accidents wouldnt have occurred if a maintenance technician spotted and fixed a fault before something serious broke. With most airplanes flying less than ever, proactive inspection and maintenance is probably more important than ever. Our notion of this is off-annual inspections of the engine and prop for emerging faults, battery capacity tests and regular oil analysis. A thousand bucks will go a long way in this arena.

Number 7

Seatbelt Harnesses

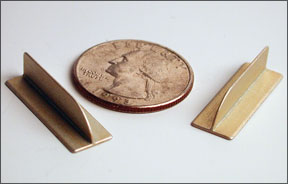

Late-model wonderplanes like the Cirrus and the Diamonds are notably

250

crashworthy, but its no secret that older airplanes arent. Seatbelts are a player in this grim calculus and even though many older models have shoulder harnesses, they arent necessarily good shoulder harnesses.

New and improved belts are available and these vary in price from around $100 to more than $1000 for a set of new four-point harnesses for the front seat in a Bonanza. Belts are passive safety devices not nearly as sexy as weatherlink or a traffic minder. But if you need them, you’ll need them badly and they simply have to work. See

Aviation Consumer December 2006 for a complete review.Number 8

406 MHz ELT

ELTs have been mandated in light aircraft since 1974 and in the intervening three decades, they havent compiled an impressive performance record, in our opinion. Thats because 121.5 MHz ELTs havent proven reliable, often failing to activate and are sometimes difficult to locate even when they do. Further, false alarms have been numerous and a nuisance.

The new 406 MHz ELTs are just becoming market ready and not many owners seem to understand that 121.5 MHz wont be satellite monitored after February 2009. That means if you crash in the boonies and you want to be found, a 406 MHz will actually make that possible, especially if its equipped with GPS, which the emerging models will have as an option. For about $1000, 406 ELTs look to be meaningful, high-value survival enhancers to us and the technology that may finally deliver on the failed promise of ELTs. If a 406 beacon isn’t in the cards, consider a personal locater beacon instead.

Number 9

Cabin Airbags

Well go out on a limb ahead of having reliable data on the effectiveness of airbags in light aircraft. These products are just becoming available in OEM aircraft such as Cirri, Cessna and Mooneys and STCs for older aircraft are in the works. For about $2500, we think fitting at least the pilots seat with an airbag is a more worthy safety investment than other high-dollar improvements. See

Aviation Consumer January 2007 for more.Number 10

Vortex Generators

This may be one you havent thought of and you arent alone. For our

Used Aircraft Guides, we review several thousand accident reports each year and we note, as does the Nall report, that collisions with terrain and obstacles account for more than 450 accidents a year, an astonishingly high number, driven by the fact that all accidents eventually impact the ground.At first blush, that would argue for buying terrain avoidance equipment-genuine TAWs or its non-certified equivalent. But the flaw in this logic is that most of these accidents don’t involve pilots flying unawares into the dirt or trees, but willful buzz jobs or low flying or loss of control during the approach phase of landing, often due to incipient stalls or mushing. Good judgment would help the pilot avoid them, but having gotten into the corner, more margin on stall and lowspeed handling might save the day. For between $500 and $1500, VGs are easy to install and work passively and especially valuable for twins. (See

Aviation Consumer February 2006 for a full report.)Chinese Menu

Conspicuously absent from our list is one of the most popular avionics upgrades: traffic awareness/collision avoidance equipment. Our reasoning is simple. At prices ranging from $10,000 to $20,000, this equipment is simply not a cost-effective safety enhancer. There are typically about 10 midairs a year and, surprisingly, the lethality of these accidents is 50 percent, lower than in VFR-into-IMC or weather-related accidents.

Its not that we think collision avoidance gear isn’t a good thing or that it doesnt perform. It is and it does. Its just that it requires spending a pile of money to address a relatively small risk, probably at the expense of deferring investment in things that mitigate larger and well-documented risk, such as weather-related accidents or runway loss of control. You could argue that 10 midairs represent a bigger risk than five thunderstorm accidents, but weather is a much broader risk than just thunderstorms.

Similarly, we don’t have backup gyros or vacuum systems or terrain awareness on our must-have list for the same reason. There are more immediate concerns, in our view. On the other hand, if you fly serious IFR and have invested in all the obvious safety enhancements, a backup gyro might rise to the top of your list, even though it isn’t on ours. If approaches in real weather are your thing, terrain awareness equipment may be a priority due to your exposure profile. But the big picture numbers don’t identify it as a big risk area.

The point of this exercise is to adopt a hierarchical approach to safety-related aircraft investments based on a cold analysis of where the real risks lie and not to succumb to gadget fever to address smaller risk areas by spending a lot of money. The latter results in “between-the-ears” safety enhancement; you may feel safer, but the reality is that youve left large risk segments unaddressed. Mundane training and upgrades like seatbelts will never be as sexy as a new GPS or a traffic minder. But they may be more likely to save your life.