Denial can be a useful thing when it comes to getting the job done. Ive done my fair share of flying overwater and out of gliding distance to land, and just rationalized that the odds were slim of ditching and Id figure it out when it happened. The reality was that I didnt have a clue what being immersed in an aircraft would be like. I had no plan, and that meant that if the aircraft did anything other than stop upright and floating, I probably was going to the bottom wearing a 3000-pound aluminum suit. The point of egress training like we sampled at Survival Systems Inc. is to give you that plan. It doesnt so much teach you how to egress your specific aircraft (although they do their best), but it gives you a system to stay oriented and get out. And, more importantly, it gives you a chance to practice while clothed, upside-down and underwater.

Theory and Practice

Survival Systems has been around since 1982 when the company was founded in Halifax, Nova Scotia. Their current headquarters is just a short walk from the ramp at Groton Airport in Connecticut. They also have a seasonal location in Kenai, Alaska, and several military installations. In fact, military and government agencies represent 50 and 20 percent of their clientele respectively. The remaining 30 percent is almost entirely corporate aviation.

GA pilots taking their aircraft ditching course (they offer many other non-aviation survival courses) represent just a small fraction of what they do, and this shows in the classroom session that takes the first half of the one-day program.

The class uses up the obligatory Powerpoint slides bulletpointing the stages of hypothermia and common aircraft survival equipment. There are written materials,

but we felt they were poorly integrated into the live presentation.

Far more motivating is an effective use of video. They have both the footage of a CH-46 helicopter rolling off a ship and into the ocean during a botched landing in 1999 (it sank in 40 seconds) and the gripping, first-hand account of one of the Marines on board who managed to claw his way out. Its about this time you starting getting nervous about the afternoons practical session.

There’s also some telling video on Cold Shock Response thatll remove any illusions you might have had that you could perform just fine after a dunk in the Atlantic in January (although if youve got a bit of extra body fat, your odds do go up).

One thing we wished wed seen more of in the morning was information on the actual ditching of the aircraft. The course covers securing yourself for the ditch, but there’s nothing on the flying technique involved in making a good ditch.

We understand that this may simply be too far outside their field of expertise, but you may want to supplement your study with some other sources for a full ditching plan. The course also feels pitched more to rotary wing than fixed wing, but given

that offshore oil companies flying helicopters are a big customer, thats not surprising.

The classroom time did offer some information gems. Which side of the aircraft do you deploy the raft on? (Hint: Downwind is wrong.) Survival rafts have a sponge to get out the last of the seawater that gets inside. Cut this in half before you use it, so the unused half can be used to collect fresh water for drinking. The class time also allowed for good sharing between the participants and working out of questions the instructor didnt have a ready answer for.

The critical part of the morning, however, is prep of the techniques you use in the afternoon. Survival Systems method is all about keeping a reference point to stay oriented to the aircraft, no matter what position its in or whether you can see the exit or can see nothing at all.

Youre briefed to stay belted in until youve found your door and opened it. Then you get a reference on the aircraft with one hand before unbelting and having your own buoyancy roll you about. Sounds easy enough in the classroom. You start feeling less sure when you change into the flight suits and water shoes you’ll be

wearing in the pool.

In the Tank

Any shortcomings of the morning are more than made up for in the afternoon. Our instructor, Glenn LaMarque told us that morning, “You will get water up your nose,” and he wasnt kidding.

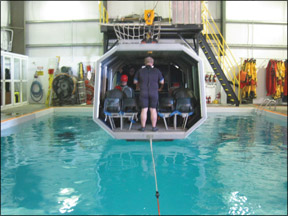

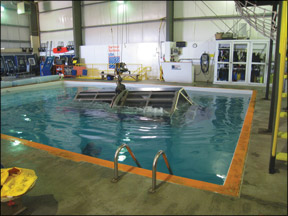

The Modular Egress Training Simulator (METS) used for the Groton course is reminiscent of a 10-seat aircraft fuselage configurable with various types of doors at every seat. Its attached to a hoist that can position and lower it into a 14-foot-deep pool. Survival Systems also has several smaller METS systems to represent different helicopters and other vehicles that might end up the wrong way in a deep pool someday.

The dunking doesnt happen right away. The big METS also has couple of flame trays in the ceiling to practice putting out a fire. This is coupled with a smoke machine isn’t particularly frightening, but does get the point across about how challenging smoke and fire in the confines of a cockpit would be. Step two after the fire is getting out of the METS sitting on the waters surface and into a life raft.

Practice for the next time youre floating on the Hudson.

Then its dunk time and there’s little bother with warming you up. The first dunk will be underwater and inverted, although they cut you the slack of leaving the door removed-the first time. Five runs in the sim are done, with it going under and rolling to different orientations. For the last two, its assumed your primary door is jammed and you must work across the sim to a secondary door.

The course is tailored to each student, so if youd be expected to assist unknowing passengers out in the real world, you can practice it here. Fewer students can mean more runs. You can do it with your eyes closed or in real darkness, too.

The METS layout and door options offer enough variability to practice having doors next to you or working your way back to a cabin door. You wont care that the door handle doesnt match your bird, and the body memory of the practice wont suffer for it. Practical tips are drilled here too, such as unwrapping your thumbs from the

control yoke so they wouldnt break were it a real ditching and impact.

The first dunk is a shock and we partially botched the procedure, but it turns out there is more time than you might think to get oriented before acting. They are right when they say you need to stay strapped in to get and keep a reference before finding a way out. If you follow the procedure, you’ll usually be up to the surface in 10 seconds or so.

That frame of reference is probably the most valuable take away from the course. Five dunks in the METS isn’t going to make you an expert at getting out of your aircraft in a real-world ditching, but it gives you some concept of what it might be like. The experience is realistic enough to be seriously unnerving and lock the techniques into your memory, but not so real that you might actually, well, drown.

There is at least one wetsuited instructor for each two students and there are two divers in the water as well. If you need help getting out, theyll provide it, but you’ll pay for it by doing that simulation again. We saw that these folks were great at projecting calm and allaying fears. One instructor told us hes seen people in tears

before getting in the tank and underwater 20 minutes later.

With the dunking done, the course continues to include a drop to the water, inflating life jackets and getting into life boats. There’s also an opportunity to climb into a basket and collar to simulate a helicopter rescue from the open ocean. The pool is a balmy 85 degrees, but after a few hours of this youre ready for the final rescue and a trip to the showers.

Net training Value

At $650 for the day the course isn’t cheap, but we think the course offers real value despite improvements wed like to see. Survival Systems will run the course on demand, and will schedule it with even just one student. They also have a small mobile system that can travel to a pool near you for $250 per person plus travel expenses.

There are some competing companies out there. The Marine Survival Training Center at the University of Louisiana uses a METS made by Survival Systems. There are

several small outfits as we’ll in the Gulf region and some in Canada (Aviation Egress Systems and Pro Aviation Safety Training). These smaller outfits tend to use one-person dunkers, but they may offer better convenience for you or a lower price.

Its hard to argue with Survival Systems experience, though. Since they started the business and combining the numbers for all their civilian and military facilities, the company has run about 70,000 people through different underwater egress courses.

Company lore tells of one student

who finished the course and ended up ditching for real 36 hours later. Were told his first thought was simply, “Im going to get water up my nose again.” If thats what the fear of ditching can be reduced to, wed consider the training time and money we’ll spent.