If the basic idea behind the ELT-you crash, it tells the world where you are-was laudable, the performance of this technology has been anything but. Even the new-generation of 406 MHz ELTs havent proved much better and are hardly flying off the shelves. From this conundrum emerges a niche market for portable satellite vehicle tracking devices and personal messengers. This technology has been around for awhile in the transportation industry, but lately it has made inroads into the sporting and outdoor markets with a device called the Spot Satellite GPS Messenger, which recently introduced its second generation model. Another company, the New Zealand-based Spidertracks, has been marketing its own satellite tracker called the Spider S3. Although these devices use different satellite systems-the Spot uses the low-earth orbit Globalstar system, the Spider uses the 66-satellite Iridium communications network-the two gadgets work on the same principle. They rely on GPS to establish an accurate position, then communicate this through the commercial satellite networks to either rescue agencies or to public or private view Web tracking, or both, customizable by the user. The concept is fundamentally different than an ELT, which activates only after the crash, and then none too reliably, and then transmits a distress signal to a dedicated satellite network. Satellite trackers, on the other hand, lay down a path of electronic bread crumbs in near real time, providing searchers with accurate position datums from which to begin looking for a downed aircraft. Furthermore, unlike an ELT, whose signal is trackable only by government agencies, a satellite trackers data can be constantly monitored by people with a greater interest-family, friends and business associates. Think of it as do-it-yourself SAR. The purveyors of these gadgets are careful not to call them beacons, but satellite trackers or messengers. Nor do they necessarily claim theyll function as an ELT does, nominally activating during or after a crash and remaining on. What they do claim is that this inexpensive technology will reliably track vehicle or personal movements and relay that data to interested parties.

The Spot messenger first appeared in aviation markets in 2008, when Spot International sponsored a promotional deal at EAA AirVenture. The original sold for $169.95, plus the cost of the satellite tracking service. Last fall, the company introduced a follow-on model, the Spot 2, which is smaller and equipped with a redesigned button set.

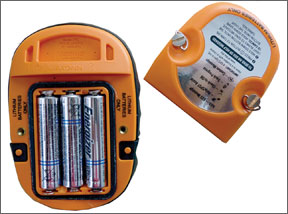

Overall size is 2.2 by 3.6 inches by 1 inch thick-about the size of a cigarette pack. Its available in silver or bright orange and consistent with its sport/recreation use, the company says its waterproof to a depth of 1 meter, although it doesnt float. Price is the same as the original, although you can find it discounted for as little as $120.

The Spot is powered by three lithium AAA batteries which the company says will last about seven days for normal, always-on tracking and about six days in SOS mode. Battery life is said to be three months for powered-up standby mode.

The Spot has only five controls: a help assist button, a check-in/OK button, a custom message key, a track progress button and an SOS button. Once the unit has found itself via GPS, pushing the track progress button will send a waypoint every 10 minutes for 24 hours until cancelled. These waypoints are viewable in the personal account section of Spots Web site and are plotted as numbered waypoints with lat/long data and time, but no speed or vector information. The Web and tracking maps can be publically viewable. Confirming the Spots initial position with the Google satellite view, we found it to be accurate within about 10 feet.

Spots OK/custom message function allows you to send a routine how-goes-it update to your account, which can also include a pre-programmed personal SMS text message, say something like “Landing in 10 minutes.” Pressing the OK button e-mails that message to your selected contact list, along with the time and your position.

(You cant change that message in the field, unless you have access to your account via the Web.) Simply pushing the button sends the message on its way, sent three times during a 20-minute period. You can send the OK/custom message during routine track progress and it will go out immediately.

The Spot has two dedicated buttons that live under protective covers. The Help/Assist is a sort of non-emergency option that, when activated, will send a pre-programmed I-need-help message to the sources of your choice. These can be the same list of contacts you use for the track progress messages or you can arrange for them to go to service providers offering roadside or other assistance. The message is sent every five minutes for an hour until canceled, which can be done at any time.

On the right side of the unit, also under a protective cover, is the SOS button. Pushing this one immediately sends a distress message to the GEOS International Emergency Rescue Coordination Center, which then notifies local responders. The message is sent with pre-programmed and position data every five minutes until its cancelled or the batteries die. Both the SOS and assist messages are sent whether the Spot has GPS position data or not. GEOS monitoring is provided in the basic service plan, so the last thing you want to do is a push-to-test to see if it works. For an additional $12.95 a year, you can buy a GEOS member benefit to cover up to $100,000 in SAR expenses.

In principle, the Spider S3 performs similarly to the Spot, but its more expensive to buy and operate and based more on the commercial vehicle tracking model than the sport or recreation model Spot is built on. Its tracking is also more robust and data rich and, at least according to our brief tests, less likely to fade.

The device itself is larger, measuring roughly 4 inches by 3 inches in a trapedzoidal, low-profile shape. No batteries, though, only ships power through an accessory plug (10 to 32 volts), so if youre thinking of this unit doubling for outdoor or sport use without power available, it wont do that. No external antenna is required; all you need do is place it where it has a clear view of the sky.

The Spiders operating mode is simpler than the Spot: You simply plug it in, wait for it find the GPS and Iridium satellites and then tracking starts. There are actually two versions of the hardware, the S3, which is a consumer-grade perch-on-the-glaresheld design and the S2, a ruggedized, waterproof version designed for commercial use. The S3 sells for $995, the S3 for $1795.

The S3s interface is simpler than the Spot. It has only three buttons-no on/off switch-you just plug it in and it fires up. Once it finds itself, it reports a single position datapoint. Pushing a button labeled “watch” starts the track mode, which reports additional positions after the device moves at at least 40 knots. It will then report position every two minutes. The datapoints are more detailed than Spots, offering lat/long, time, speed, track and altitude. In our view, the additional data could be a meaningful plus for SAR responders. The Spider paints quite a detailed picture of your movements, with position reports at closer intervals than Spots.

If the Website doesnt receive good data for a period of 15 minutes, it will alert your contact list. If the contacts don’t respond after another 15 minutes, a so-called second tier alert will be sent that can-but doesnt have to-go to your designated rescue services. All of this can be customized on the Web interface, including the tracking interval, which can be as little as one minute. Spidertracks views the monitor mode as something to be used only when flying in hazardous areas, but we suspect most users would want it on all the time, since detailed breadcrumb tracking is what makes a satellite tracker superior to an ELT.

The system can be configured to send custom messages-you program these on the Web site-corresponding to “mark” button pushes. One for takeoff time, say, two for an enroute check, three for landing and so on. These can be set up to be sent automatically at certain speed thresholds, say 60 knots to indicate takeoff or under 30 to indicate landing. The Spider has an external keypad, but its for extended functions related to alerts, monitoring and pre-programmed text messages, not discrete messages on the fly. Although it wasnt available when we tested the Spider, the company does plan to offer a text messaging system which would connect the unit to a smartphone through Bluetooth.

Managing tracking and alerts for both devices is done through dedicated Web sites. We found that both sites were generally logical and easy to use, but we had some trouble initially registering to the Spot due to a phone number format not explained on the site. It took a call to customer service to get that sorted out.

Similarly, the Spidertracks site was not yet fully functional when we tried the unit, although it was straightforward enough to get the device operating and to see its tracking results on the Google maps the system uses. The instruction sheet with the Spider is somewhat confusing and it took a call to the company to sort out some questions. Here, Spot is better because it has a U.S.-based support line and also a series of short technical videos explaining the products principle features.

The graphic on page 6 shows how the two compared on a couple of short test flights. As you can see, they are somewhat comparable, however, given its more frequent position reporting, the Spider paints a much more detailed picture of the aircrafts track, offering more data than the Spot does.

Moreover, the Spot proved, well, spotty at times. It would seem to track well, then skip a few beats, and pick it up again. It appears to be quite sensitive to the antennas view of the sky. We had it attached to a downtube in Cub and vibration caused it point inside the aircraft rather than outward toward the windshield. This caused it to stop tracking. As for the Web interface and notifications to your contact list, again, the two are functionally comparable. We found that the primary messages went to our designated list as they were supposed to and anyone we thought remotely interested in the peripatetic albeit short-range wanderings of a J-3 Cub could log in and find out more than they ever wanted to know.

Purchase and operating cost is the major point of departure here. At nearly $1000, the Spider is more expensive by a factor of about six. Its complex, multi-tiered data plan based on the Iridium system does give you some flexibility in what you pay. For example, lets say you use the Spider eight hours a month. The basic fee-called the Regular Flyer-is $15 a month, plus $4.50 an hour for every hour you go over that. All but the most basic plans require a one-year contract, so figure $180 a year.

Spots basic plan is $99.99 a year or $199.98 for two years. (Whatever happened to the volume discount?)

If you add the track progress feature, its another $49.99 a year and the GEOS insurance ($12.95), youre up to about $160 a year-$20 cheaper than Spider.

So whats the value equation here? Here it is, in our view: With its two-minute report rate, in a 150-knot airplane, the Spiders maximum circle of probability is 5 miles, which is how far you’ll fly between reports. With the Spot, on the other hand, it could be as much as 25 miles, but it could be a lot more if it misses a report or two. It could also be less, depending on when your imaginary crash occurs.

The Spider gives the advantage of a more complete position report. On the other hand, it costs a lot more and you cant take it hiking or fishing with you, unless youre fishing from a boat with an electrical system.

Given these factors, we think the two are close to being comparable values. The Spot isn’t as robust, but it costs a lot less and you can use it as a multi-purpose sports/recreation backup plan, in addition to being an aircraft safety enhancer. If all your outdoor activities are limited to the cockpit of a fast airplane and youre obsessive about having razor-sharp SAR tracking, the Spider is the better choice.