Nobody likes to be on the receiving end of a harangue and we’ll wager that not many of us like delivering them, either. And thats the problem with magazine articles reviewing aviation safety equipment. What starts out as friendly advice on buying safety gear devolves into a lecture from your Aunt Hazel on the perils of running outside with your hair wet and, oh, by the way, when are you going to get a real job and stop hanging out with those loser friends of yours? With this in mind, were going to alter course and withdraw our previous recommendation that every GA airplane should have personal flotation devices as standard equipment. The fact that few actually do shows how seriously owners take this suggestion. So heres our revised thinking: If you have no significant overwater risk, spend your money on training, a backup gyro or a fire extinguisher-any of which youre more likely to need than a life vest.

But if your exposure to landing in the water is substantial, PFDs ought to be on your list of required basic gear. Whats substantial risk? Thats eye-of-the-beholder territory. Crossing the Mississippi at 1000 feet or Delaware Bay at 5000 feet twice a year might not qualify.

But weekly flights to Catalina, jaunts to the Bahamas or coastal forays in Florida or the Great Lakes certainly do. There’s a gray zone between these two extremes bounded by your budget and how much of it you wish to spend on being prepared with equipment you may never need. If budgets don’t limit your safety considerations, buy the best PFDs you can find, one for each seat.

There are dozens of choices in the aviation PFD market, many of them unsuitable for the nature of GA overwater flying. if that sounds like were dismissing an entire class of perfectly good products, in a sense, we are. We reached this conclusion during our research following a conversation with richard Switlik, whose Switlik parachute Company makes a line of well-regarded safety equipment, including pFDs. Switlik contends that for piston GA flying, flotation equipment is useful only if its immediately available when needed and that argues for actually wearing it during the overwater legs.

Based on our research with ditching survivors-for a report on that, see the sidebar on page 19-we think Switlik is right. its folly to think crew and passengers can don a pFD under duress, secure it and egress safely. this is aggravated by the reality that pilots don’t always brief passengers on how to don a vest because the vests are stored in their sealed plastic packets, often utterly out of reach in the baggage compartment. Our sea trials prove that vests can be donned.

At this juncture, were taking Switliks views to heart and arguing against airline-type vests and in favor of PFD designs intended for constant wear, of which there are many in the marine and aviation markets. To be sure, there are a handful of excellent airline-type vests available, but they arent intended for constant wear. Theyre designed to be light, storable and inexpensive.

In our view, this isn’t the design brief for a GA vest, which is more likely to actually be needed by occupants who wont have a flight attendant to help them don it. Furthermore, the price difference between constant wear and airline vests isn’t as great as it once was.

With these requirements in mind, we joined our marine division in a round of testing constant-wear vests intended for the marine and aviation markets. There are minor differences between the two types, but for our purposes, we think the products are similar enough to work in either or both applications. The most important difference is automatic inflation capability, which may be wanted for marine use but should not be considered for aviation use. The last thing you want in trying to escape a sinking airplane is an uncommanded inflation of a PFD.

388

APPROVALS, REQUIREMENTS

Owners who fly private airplanes overwater are often confused by the survival equipment requirements. This is easily clarified. For small aircraft Part 91 operations, there are no requirements to carry overwater survival gear. Period. It may be dumb to fly to Key West without flotation equipment, but its legal. The oft-quoted 50-miles-from-shore rule is found in 91.509, but it applies only to large and turbine-powered multi-engine airplanes, not light piston aircraft. Large and turbine aircraft require approved flotation gear, which means equipment that meets TSO C13, which most airline-type vests do. Obviously, operators of these airplanes cant use marine vests.

And were not badmouthing TSOd products. They meet certain requirements with regard to manufacturing quality, testing procedures, performance and durability that we think are desirable. The most important, in our view, is the requirement for minimum buoyancy-35 pounds for an adult-and the ability to right an unconscious person in the water.

Interestingly, boaters have more stringent requirements for PFD equipage than do aircraft owners. The Coast Guard and states require USCG-approved PFDs aboard recreational vessels. Coast Guard approvals require demonstrated performance in buoyancy, puncture resistance of the material, and seam strength, among other requirements.

Worth noting is that some vests meet or exceed both the TSO and Coast Guard requirements, but don’t actually don’t have approvals under either requirement. Indeed, one of the top performers in our tests, Crewsavers CrewFit, isn’t Coast Guard approved, but was among the best in construction quality, performance and comfort.

On the subject of comfort, this is a critical consideration for a constant-wear vest and an enduring drawback of airline-style vests pressed into service for constant wear. Airline vests are large, floppy expanses of yellow material that can be hot and miserable to wear. Some have scalloped seams around the neck which become irritating in minutes, never mind a two-hour overwater flight. The harnesses and straps tend to be minimal and annoying and exposed oral inflation tubes snag shoulder harnesses. None of this does a thing to calm passenger anxieties. In numerous flights overwater, we have found that nothing quite says were going to crash like parading around the ramp in a bright yellow airline vest prior to departure.

Constant wear vests address this by containing that expanse of yellow or orange material neatly folded inside a resilient cover or pouch that both protects the vest against punctures and abrasions and keeps the cell material unobtrusive. Nervous passengers are less unhinged when asked to use a constant wear vest. The outer covering serves another function: In some designs, it provides the means to place pockets in the vest, which can carry signaling devices and other gear that may be the only thing you have when you exit a sinking airplane.

Among the several design protocols for PFDs is dual versus single-cell flotation. Some years ago, the FAAs PFD TSO was amended to allow single-cell designs, but we don’t like that idea much. Having inflated dozens of these things, weve seen more than one cell failure in vests that havent been treated kindly in storage. And most wont be, nor are they likely to receive the periodic inspection the manufacturers recommend. For that reason, we prefer dual-cell designs. If budget allows only single-cell, just understand that these represent a lower standard of reliability, even though their in-water performance may be good.

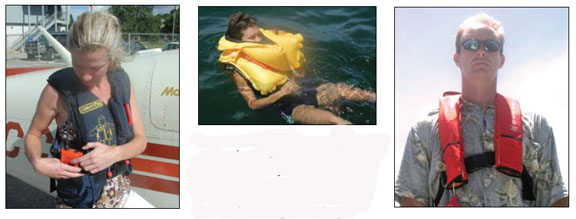

WHAT WE TESTED

Joining forces with our marine division, we tried nine marine vests and six aviation-specific designs. Just for good measure, several of the aviation models were airline-type designs, even though thats not the focus of this report. Only the constant-wear models are listed in the table on page 16. We evaluated each product across a range of criteria. How easy and comfortable are they to don? Can they be donned in the airplane or in the water? How we’ll designed are the fasteners and straps? We also tested access to the manual inflation tubes and the vests ability to right a person from a facedown float.

We tried all of the vests at sea, in the Gulf of Mexico with water temperatures in the high 80s and a gentle swell. We tried to don some of the vests while in the water and, as we said, doable under controlled conditions, but not recommended. This further argues for wearing the vest when overwater, so youre ready to inflate it once youre clear of the airplane.

TOP PERFORMERS

Without regard to marine or aviation applications, we deem three products to be the top performers in this group: Switliks Helicopter Crew Vest, Crewsavers CrewFit and Eastern Aero Marines Bravo constant-wear vest. Switlik has been a consistent winner in our previous trials. At $344.24 retail, the helicopter vest is clearly professional-grade equipment meant for pilots who fly overwater frequently and need reliable, comfortable flotation.

Admittedly, at this price point, it will be beyond the interest of many owners; few will want to equip every seat with a helicopter vest, although buying one for the pilot seems reasonable. (Switlik also offers a helicopter passenger vest that is similarly constructed, albeit without the pockets. It sells for $$262.75.)

The helicopter crew vest consists of a Switlik dual-cell vest wrapped in a robust nylon cover with Velcro closures and dual inflation tubes. The back of the vest is a mesh material thats cool and comfortable and the plastic closures are we’ll made and easy to adjust. Two expansive Velcro-closed pockets on either side of the vest are large enough to carry a PLB, mirrors, whistles, sea-dye or a radio or water bottle. The vest also has a water-activated light.

In the airplane, the vest is comfortable, if a bit bulky. In the water, it has 38 pounds of buoyancy and it inflates vigorously, clamping the neck firmly, almost to the point of discomfort. This can be relieved by releasing a little gas pressure from the oral inflation tubes. We found it all but impossible to get face down in this vest.

We tested a pair of UK-made Crewsaver products, the Crewfit 150N and the Crewfit 275N. Our 150N was a standard vest, while the 275N had a harness and single D-ring intended for on-deck security on a vessel but not needed for aviation. We didnt much like the buckle that comes standard on the harness version, which proved difficult to tighten. The plastic snap-lock buckle with the metal tension adjustment on the 150N worked better, in our opinion.

The 150N was the more comfortable vest in the water. When inflated, it has more than enough room around the wearers chin and face. The 275N in the Crewsaver Crewfit name stands for 275 Newtons of buoyancy. Thats almost 62 pounds-and it shows. Once inflated, the 275N can only be described as huge, with each chest cell measuring about a foot in diameter. There’s not even a remote chance of getting face down in this thing. As noted, neither of these vests are USCG approved, but both are top quality products certified to European standards.

Rounding out our top three is a relatively new product from Eastern Aero Marine called the Bravo. Its a constant-wear design constructed of a heavy mil fabric stitched to a sturdy nylon web harness with a stainless steel rather than a plastic tensioner. It has both a whistle-attached by a lanyard-and a water-powered light, plus reflective tape on the cells. Two small pockets suitable for a mirror, dye or small medical kit are sewn on the front of the vest. Both in and out of the water, the Bravo proved comfortable. But it has one significant drawback: Its a single-cell design. Given its otherwise excellent features, however, we could live with that. (Most marine vests are also single cell.)

OTHER CONTENDERS

Frankly, although were making choices here, we don’t consider any of these products unacceptable. In our second-choice-nearly-as-good group are two so-called quick donning designs, from one Eastern Aero Marine, the other from Stearns. Quick-donning vests qualify as constant wear, in our estimation, because they live in a small fanny pack that straps to the waist, with the pack riding on the stomach. When needed, you pull the vest out of its pack and slip it over your head. It takes less time to do that than to read about it.

The Eastern Aero Marine KSE-35HC2L8, which is intended as a constant-wear product for the helicopter market, fits into a small squarish pack attached at the waist with a plastic clasp on a nylon web with yellow tabs so they can be located and tightened. This vest is a dual-cell design and meets TSO C13e. Its comfortable out of the water and moderately comfortable in the water. The neck ring is neither gusseted nor scalloped, yet it still proved to be slightly irritating. At $63.85 retail, its the top value in this group. For $72.46, you can buy it with a heavier duty pouch.

The Stearns version of this design is the Model 0375 Inflata-Belt, at $94.99. The directions with this product recommend inflating it first, then pulling it over the head, a process that obviously requires swimming ability. (Stearns says the 0375 shouldnt be used by people who cant swim.) Its Coast Guard approved but not TSOd. This vest was, by far, the most comfortable in the water, perching the wearer in a relatively luxurious back float with comfortable behind-the-head support.

We also tried the MD3003 and the MD3031 from Mustang, both updated versions of previous products weve tested. These are just two of Mustangs many similar products. Both Mustang vests are similar to the Crewsaver Crewfit 150N. The MD3031 carries a spare CO2 cartridge, making it stiffer and less comfortable than the MD3003.

Buckles and belt tensioning hardware on both Mustang units are virtually identical to those on the Crewsaver 150N and both performed similarly in the water. If availability of the Crewsaver proves problematic or you need a USCG-approved inflatable for dual use in a boat and airplane, wed opt for either of the Mustang units.

CONCLUSION

Emergency safety gear has come a long way in the past decade and these vests prove it. There are more quality vests to choose from than ever, at a range of price points. We have only touched on a selection of constant-wear models from marine and aviation markets and certainly not all of them. We think that any owners who have significant overwater exposure risk should consider constant-wear vests and use them during the higher-risk segment of the flight.

The less durable fallback is TSOd airline-style vests stowed in seatback pockets. We don’t view this as an entirely irrational decision, since its based on how you personally measure safety against cost and because, well, we don’t want to be mistaken for your Aunt Hazel. The EAM pouch is a good compromise, since its TSOd and in the price range of airline vests.

But if youre not wearing the vests over the water, just make sure theyre readily at hand if you actually need them and at least brief passengers on donning and use.

CONTACTS/SOURCES …

Crew Saver

44 (0) 23 9252 8621305-358-7455

(U.S. source)www.crewsaver.co.uk

Eastern Aero Marine

305-871-4050

http://www.theraft.com/

Mustang Survival

360-676-1782

http://www.mustangsurvival.com/

Stearns, Inc.

800-333-1179

http://www.stearnsinc.com/

Switlik Parachute Co.

609-587-3300

http://www.switlik.com/

Plastimo USA, Inc.

941-360-1888

www.plastimo.com

Sportys Pilot Shop

800-776-7897

www.sportys.com

pyacht.com

877-379-2248

www.pyacht.com