When the dimensions of the COVID-19 pandemic emerged in mid-March 2020, airline bookings shortly fell off a cliff and the rest of the aviation industry held its breath. And sure enough, the phones stopped ringing in the finance offices where aircraft loans originate. Prospects seemed even grimmer than during the 2008 deep recession.

But within a month, in a surprise development no one expected, the market for loans on used aircraft came roaring back and for some banks and lenders, now appears to be stronger than ever. “The activity level is unbelievable. I can’t tell you how busy we are. It’s amazing,” says Bob Howe of Dorr Aviation Credit, a veteran finance brokerage house with more than 50 years in the field. If would-be buyers are taking a wait-and-see attitude, it’s not evident to the folks making aircraft loans.

But what is evident is that banks are sitting on piles of cash that nervous investors have dumped into CDs that may return a pittance but that are also safer than the stocks that took a dive in mid-March. They’ve since recovered. During the same week, the Federal Reserve dropped the benchmark interest rate to zero and announced plans to buy as much $700 billion in government and mortgage bonds.

Between the stimulus and rate cuts, the economy was pumped with record amounts of liquidity. According to the Federal Reserve, the M2 money supply swelled 20 percent, from $15.3 to $18.3 trillion from December to July. The M2 supply consists of cash deposits, checking accounts, savings and money market securities.

HISTORIC FALL

The last major shock to hit the economy and aviation was the financial meltdown of 2008. Compared to the COVID-19 pandemic, that was a slow-motion train wreck that hit bottom in 2009 with a slow, sputtering recovery that carried on until 2012. It has yet to return to pre-downturn new aircraft sales volumes.

The pandemic downturn, if it can even be called that, began in mid-March and extended into early April, brokers told us. The phones stopped ringing and the rest of the economy teetered on the cliff. “I think everybody had to take a deep breath and digest what was going on. A lot of our customers use aircraft as a business tool. They feel the impact of a pandemic very directly,” says David Savoie of U.S. Aircraft Finance, a direct lender who specializes in light aircraft up to heavy singles and twins.

Three other brokers we spoke to reported a similar experience but the slowdown was almost too short to notice. “When the Fed pushed down the rates, we saw a significant upflow in activity for refinancing. For us, March, April and May was not a lot of new business, but in June, we started to see a huge uptick in new business,” says Jim Blessing of Airfleet Capital, a leading brokerage house. And loan inquiries haven’t slowed since. “It’s been active for sure. It’s as busy as we’ve ever been,” Blessing told us. AOPA Finance, also a broker using outside banks, reports similar activity.

There are a couple of market shifts in this recovery. First, a long-established trend of buyers relying on their own cash reserves appears to be shifting back to leveraging purchases with debt.

This has been underway for a year or two. And second, because money is so cheap and there’s plenty of equity in owned aircraft thanks to price firmness in the used market, many owners can borrow enough to finance full upgrades in avionics, engines and paint jobs with minimum pain.

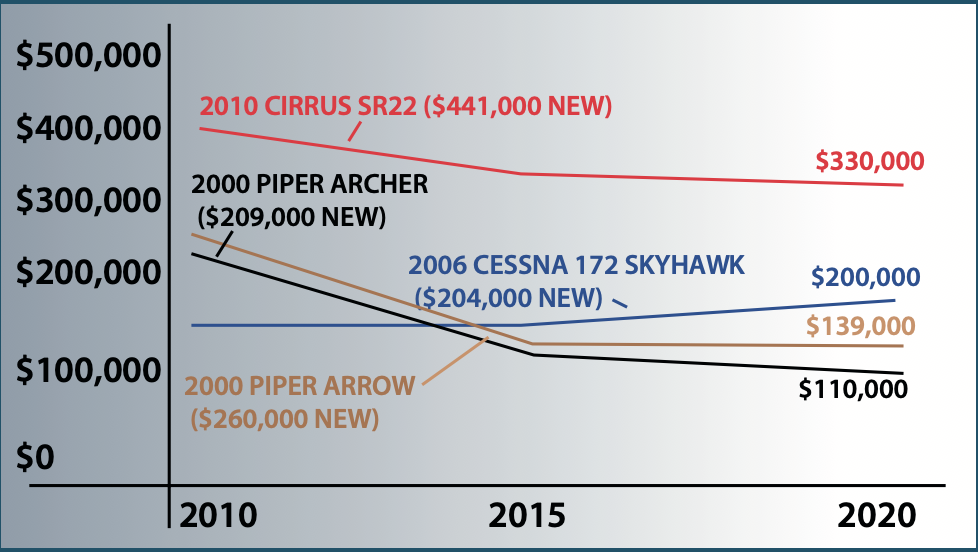

For a time there during the 1990s, the words “investment” and “airplane” could be seen in the same sentence without igniting gales of laughter. And there was some truth to it because Cirrus didn’t exist, Cessna wasn’t making airplanes and Piper was bankrupt.

Thirty years later, all three are building airplanes and so is Diamond Aircraft. But new airplane prices are at such stratospheric levels that used aircraft prices have been dragged upward, too. But there’s a problem: Good inventory is hard to come by and for older airplanes, they’re just accumulating ever more hours, making the creampuff airframe a unicorn.

For certain models, this means that the traditional depreciation curve that saw the new value tank during the first three years has flattened somewhat. For some airplanes, it has even reversed. The chart above is interesting not just for the actual values, but the directionality.

And there appear to be sharp divisions between airplanes with glass panels and those with steam gauges, especially for the Cessna 172 SP, a popular trainer. The chart shows a 2006 model with the G1000 at $200,000, but it probably understates the case. We’re seeing them listed for north of $250,000, if you can even find one. The training market is driving demand.

One caution: The values here are from Bluebook but we’re not sure how realistic they are given that accurate sales reporting is difficult to come by.

LOWEST RATES EVER

“When you’re looking at retail rates in the threes on a couple of hundred-thousand-dollar airplanes, that’s pretty hard to beat. I’ve been doing this for 32 years and I’ve never seen anything like it,” says Dorr Aviation’s Howe.

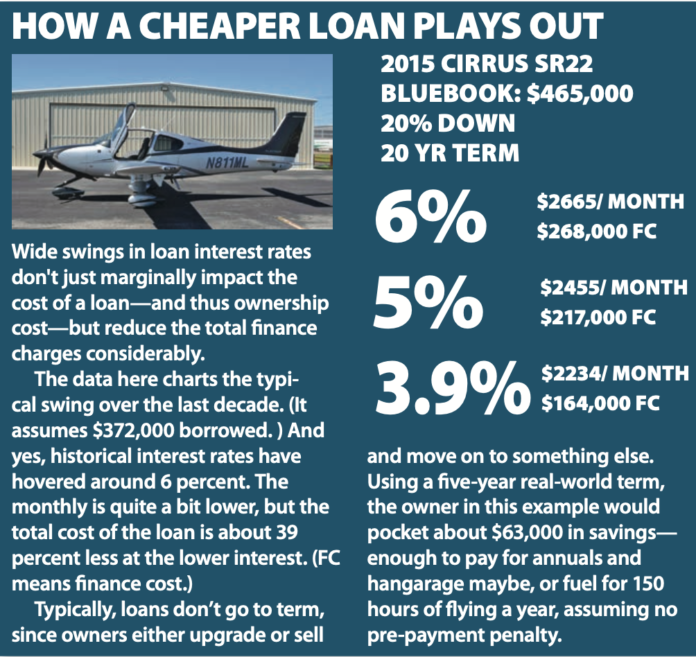

In explaining the trend from cash to loan, Blessing says buyers are adding up the opportunity costs and pushing the button for the bank’s money. “If they’re in the market and their portfolio is getting them 5 or 6 percent rate of return, then they’re in much better shape borrowing at today’s 3 or 4 percent range than they are employing that capital in a different way,” Blessing says.

And banks are willing to deal. Up to a point. When it looked like the stock market would crater, many investors fled to bank CDs and although the return is barely worth the trouble, at least they maintain value. As a result, banks are swimming in cash and, if not quite desperate to loan it out, they’re motivated to get that money working.

“In years past, we were asking the banks to sharpen their pencils. We were squeezing our yields in order to get the business going,” says Howe. “Very seldom do we have banks coming to us and saying this is our rate, can you get more deals. If we squeeze a little further, what do you think we can get?” he adds.

And what they can get is good deal for buyers. A year ago, interest rates were attractively low, but now they’re lower yet. Sub-4 percent notes aren’t uncommon and on new airplanes, the manufacturers are working deals even better than that.

For perspective, long-term interest rates have traditionally been in the 6- to 7-percent range. According to AOPA Finance’s Emily Meczkowski, small loans—say under $50,000—may still command as much as 7 percent, but those approaching $100,000 will get the better rates.

In fact, aircraft loans are cheaper now than auto loans, even for would-be car buyers with exceptional credit ratings. According to Bankrate, a credit rating of over 800 nets 4.19 percent on a new car and 4.7 percent on a used model. And there’s a reason for that.

“This is a safe business,” says Bob Howe. Banks like aircraft loans because they’re reliable with few defaults, repos and deferrals. “The other commercial lending segments in the banks are not very active. We’re finding the banks are very hungry to add loans and aircraft are a great, diverse portfolio. You’ve got multiple industries, you’ve got wide geographic diversity and from what we’re hearing, it’s not just aircraft, but boats and RVs are also in the upswell of activity,” says Airfleet’s Blessing.

When we asked if some of this buying frenzy is being driven by reverting to general aviation over fear of flying on airlines, the brokers say there’s no clear evidence to support that. “There’s some of that,” says Savoie, but no one is seeing it as a primary driver.

BUT SOMETIMES PICKY

While banks are in the mood to deal, that doesn’t mean you can waltz out of the bank with a half mil loan just on your signature. Nor can you expect to beat up the lenders much on already low interest rates. “We are seeing lenders putting minimum floors in because they’ve got minimum budgets they operate off of. Interest rates now are in the 4 percent or below range. You can get variable rates that might drop that even lower. But a lot of times, it might not make sense to take that additional risk if you’re already at a 3.9 percent rate to start with,” says Blessing.

While banks aren’t necessarily nervous, they’re being picky about qualifying candidates. Even though banks are hungry for business expansion, they we’ll remember what happened in 2008 and have established guardrails on who they’ll loan to. And unlike in 2008, some banks are trying to get ahead of potential loan defaults by offering customers payment deferrals. These can last for 60 to 90 days and can sometimes be renewed.

“The banks starting offering them without being asked. I think they were trying to get ahead of the power curve, which irritated me because they were offering them to anybody. You didn’t have to qualify. When you pay your loan, I get paid. If everybody in the portfolio wants to take a 90-day hiatus from paying their loan, I don’t have any income for 90 days. I was a little taken aback that they didn’t consult us ahead of time,” says Howe. But not many customers accepted the offer, evidently because they didn’t feel financially stressed enough to need the relief.

COVID-19 still plays in loan considerations, however. In addition to the usual background financials and credit reporting, the banks may ask brokers if customers have a pandemic plan in place in case cash gets tight. That basically means cash flow and money in the bank. “The only difference I’m finding now is that the banks are a little more keen on asking what has the COVID impact been. What’s their mid- and long-term recovery based on? We’re getting varying answers. But I haven’t heard a bank turn their nose up on a deal,” Howe said.

Generally, a credit rating of 700 or more is the magic number, but something lower is not necessarily a deal killer.

Blessing said if an owner runs a company and has a sub-700 rating because the credit gets pulled often, that won’t necessarily tank the deal, especially if the client has good liquidity and cash flow. But in the current market, even a 10-year-old bankruptcy will get a stink-eye from the bank.

All of the lenders tell us that in order to move things along, it’s critical to provide a complete application. All of them can provide the basic form online, with all the required data. But that doesn’t mean everyone fills it out. “A lot of people will just pencil whip the application, say I’ve got $100,000 in cash and my house is worth a million dollars and that’s all I’m gonna put on the form. Then we pull a credit report and find all these other debts. It takes longer means … we have to reconcile everything. It creates obstacles for turnaround time,” says Blessing.

And while Airfleet and other lenders enjoy an embarrassment of riches at the moment, they know it might not last. Airfleet was considering hiring staff to process loans, but they’re worried they won’t be able to sustain the current pace. So, they’re having existing staff handle the additional volume so turnarounds may take longer. And longer yet if they have to contact applicants for follow-up information that should have been on the initial application.

RECOMMENDATIONS

If you’re thinking about any kind of a loan for a new or used aircraft or a major upgrade, it’s a pretty safe bet there’s never been a better time to borrow money. And the happy times might not last forever if the stock market wobbles or the banks get nervous about defaults.

The typical loan term these days is 15 or 20 years, but the typical loan life is a lot shorter than that—48 to 56 months, according to Dorr’s Bob Howe. That means there’s a lot of churn in the market.

With money so cheap, does it make sense to borrow more and extend the term either as a means of saving money or leveraging purchasing power for a newer or more capable aircraft?

Possibly. A longer term will lower the payments and allow doubling or tripling them to pay it off sooner and lenders say some buyers follow this strategy. If you’re planning to pay off early, however, make sure you understand any prepayment penalties. Some lenders have them, some don’t.

Whether to use a broker or a direct lender or specialist bank is a question of price and service. Brokers will do the shopping for you based on one credit pull, while direct lenders will hit the services for each application. A hard credit pull can dent your rating five to 10 points so it may pay to shop rate ranges before making the actual application.

With so much equity in airframes, Howe said it’s not at all uncommon to issue a loan that will cover 100 percent of a major upgrade and we’re not talking piddling 10 grand spruce ups, but work north of $50,000 or more and glass upgrades can definitely go there. A year ago, that would have cost 30 percent more than it does now. And a year from now? No predictions from us.