by Kim Santerre

Are air/oil separators must-have equipment? To read the advertising claims of the two leading suppliers of these gadgets, youd assume so. One of the suppliers claims you’ll banish oil mist from the airplane belly, enjoy better cooling and longer engine life thanks to a crankcase that can be kept topped off with oil.

Are these claims true? Comments from owners flying with air/oil separators suggest that pilots who have installed them are generally satisfied with the investment, although performance may be mixed and some report no success with them at all.

We think the higher flying claims for air/oil separators are unsupported and we contend that there’s significant misinformation about what air/oil separators do. If you own a wet vacuum pump, an air/oil separator is indeed required equipment if you wish to avoid having the underside of your airplane slathered in oil mist. Absent the wet pump, we don’t agree that air/oil separators are always good investments.

What They Do

Air/oil separators do two things: They collect the air/oil mist effluent generated by combustion thats normally dumped overboard through the crankcase breather system. Second, if a wet vacuum pump is installed, they catch and return to the sump the pumps oily exhaust.

Air/oil separators vary by design but the basic idea is that oil from the engine breather vent is piped into the separator where a series of internal baffles or chambers separate the oil mist from the breather air, routing the condensed oil back to the crankcase and venting the air overboard. Ideally, if the tubing is installed correctly and the temperatures are kept high enough, moisture in the oil is evaporated, too, or at least reduced.

The theoretical benefits are obvious. Instead of dumping the oil overboard where it condenses on the belly, the oil mist goes back into the crankcase, where its re-used for lubrication and cooling. The upshot-and something variously confirmed by user reports-is that oil consumption per hour of flight declines and less make-up oil is required between oil changes. And if the oil stays in the crankcase, it wont have to be cleaned off the belly. So far, all good stuff.

But there are some theoretical shortcomings, too. In addition to cooling the engine, aircraft oil also collects and holds contaminants in suspension or in solution in water vapor. If youre returning this contaminated oil to the sump, youre obviously returning the contaminants, too. And if you use less make-up oil because the sump doesnt draw down during normal flight, youre not replenishing the sump with fresh oil. So the sicker your engine is-in other words, the more blowby it has-the faster you contaminate the sump; you have essentially created a still whose waste output empties into the crankcase. Further, avgas residue dilutes oil and make-up oil serves to restore lost viscosity. With no make-up oil, viscosity may decline.

These are the significant arguments against air/oil separators and one reason that mechanics weve interviewed don’t like them much. John Schwaner, a well-known engine expert and author of the Skyranch Engineering Manual, has this to say about air/oil separators: Air/oil separators are like hooking a line up to your anus and piping it back into your mouth. Excuse the crude analogy, but who wants the water, acids and other combustion residuals pumped back into ones engine?

Wet Pumps

Although the market history of air/oil separators isn’t crystal clear, they gained favor in the era before dry vacuum pumps displaced the wet pumps which were once considered the standard. Wet vacuum pumps are the undisputed longevity champions and routinely last the life the engines theyre installed on. One reason for this is that, as the name implies, wet pumps are lubricated with a small volume of engine oil.

During normal operation, some 20 to 50 cc per hour of oil is routed through the pump for lubrication and dumped overboard. That doesnt sound like much but at the higher end, it amounts to about three tablespoons per hour, enough to spray the belly with a wet coat of oil.

An air/oil separator returns this oil to the crankcase instead of the engine compartment or the belly. There are fewer combustion byproducts in this small discharge from the wet pump, which is primarily oil mist and some water. This assumes, of course, that the oil is changed frequently because, as noted, the oils job is to pick-up combustion byproducts and the more blowby the engine has, the more contaminants the oil will contain.

Although in new aircraft, the vacuum pump-wet or dry-is being displaced by all-electric systems that don’t use vacuum at all, many older airplanes were delivered with and still have wet pumps. These almost always have a factory-installed air/oil separator of some kind but plumbed to just the pump exhaust, not the engine breather.

The Major Players

For certified airplanes, M-20 Turbos and Airwolf are the major suppliers of air/oil separators; both companies have STCs for many aircraft. There are other separators on the market as well, but these apply to fewer airplanes.Beryl dShannon caters to Bonanzas, Comanches and some Cessna 182s and RAM aircraft has a separator for 400-series Cessnas.

Aircraft Spruce sells several models for Experimentals as we’ll as both the Airwolf and M-20 brands.

The M-20 separator appeared about seven years ago, backed by an aggressive advertising campaign that continues today. Airwolf, well-known for its remote oil mounting systems, picked up the old Walker AirSep line a few years ago after Walker got out of the aviation business. Walker still makes an extensive line of air/oil separators for the diesel engine market.

Anyone whos been around airplanes for a while will remember the Walker AirSep, which was quite popular during the late 1960s and early 1970s, when wet vacuum pumps were more common. Walker faded away with the dominance of dry vacuum pumps and, indeed, part of the Walkers comeback via Airwolf is due to the resurgence of wet pumps. Airwolf has its own clean-sheet wet pump and M-20 is selling wet pumps based on out-of-production Garwin and Pesco designs.

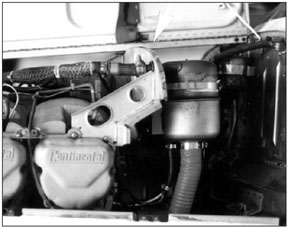

M-20 sells two models of air/oil separators: The 300 series models ($360 to $420, depending on engine horsepower) are designed to return breather oil to the crankcase, while the 600WP ($360) collects wet pump exhaust and returns it to the crankcase. If you want both functions, you have to buy and install both the 300 and 600, bringing the price to more than $700, plus the installation. The M-20 separators are small-about 6 inches high and under 2 inches in diameter-and nicely made of welded aluminum. They don’t include installation accessories, such as clamps or hoses.

The Airwolf air/oil separator uses a larger canister with a different technology that performs both the breather outlet and pump exhaust function in a single unit. The Airwolf retails for $495 and includes all hardware and excellent diagrams and installation instructions.

Although the two brands are supposed to perform the same function, their operating details are different. The M-20 separator employs baffles and internal convolutions within the cylindrical unit to capture the unwanted components of the air/oil mix, which then settles to the bottom of the chamber, where gravity returns the condensed liquid to the crankcase via a hose. The return location varies by engine and there’s no pressure in the separator lines other than what comes from the breather output.

The Airwolf system can be said to be more active. It taps a small amount of pressure from the vacuum pump for a more positive return to the crankcase thus, unlike the M-20 system, its likely to be less sensitive to how the return line is installed. Airwolf and M-20 have quite a spirited war of words on their Web sites and M-20 claims that positive pressure from the vacuum pump may be responsible for blown-out crank seals.

If this is true, we havent heard of any instances of it but its easy to test for it. Simply do a crankcase pressurization test before and after installation of the Airwolf separator. If pressurization is found post-separator installation, disconnect the separator breather connection. Airwolf uses such a small amount of pressure, however, that were skeptical of M-20s claims. In counter-argument, Airwolf says the warm air from the vacuum pump improves the separators ability to condense and return oil to the sump.

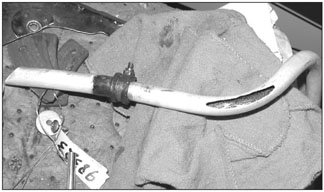

As far as installation, its straightforward with both designs, requiring about three hours of labor, not counting extra fabrication time for making a special Y-pipe for the M-20, if its needed to return oil to the rocker box area. M-20 says because oil is returned via gravity, installation of the return line is critical. For a more durable installation, we recommend using Adel clamps for the separator and lines rather than the tie-wrap method recommended in the M-20 instructions.

Airwolfs installation kits and instructions are more complete, in our view. Its shipped with all the hoses, hardware and clamps you’ll need. The Airwolf is a larger unit-more than twice the size of the M-20-so finding a spot for it under the cowl may not be easy. The weight of both products is negligible but Airwolf says its separator must be installed so its not in a blast of cold air.

Do You Need One?

No suspense here. Yes, you need one if you have or intend to install a wet pump. Of the two, we prefer the Airwolf because even though its more expensive, the installation kit is more complete and a better value, in our view. If physical size or STCs are issues, the M-20 is a second choice.Although many owners report that getting the installation just right with the M-20 can be frustrating, we agree with Bill Sandman that it can probably be done with enough patient work and re-routing of the oil return line. But this can be expensive and time-consuming, as it was for us.

As for condensing the breather output as a means of saving oil, we think this is a dubious reason for an air/oil separator. On its Web site, M-20 claims that flying with a full crankcase can make engines last up to 75 percent longer and save $10,000 to $25,000 over the life of the engine.Were aware of no credible research to support this claim and when we asked M-20s Bill Sandman for documentation, he conceded that the claim is based only on experience with a single engine-his turbonormalized Mooney 201-and no fleet data exists to verify this claim.

We are highly skeptical of the benefits of flying with 8 quarts in the sump rather than 6. Our own full versus partial-crankcase oil level tests revealed hardly measurable difference in cooling efficiency, counter to M-20s Web site claims.

For our tests, we filled our 201s crankcase to its maximum 8-quart capacity, then flew 30 to 40 minutes of touch-and-go pattern work. We then drained the sump to four quarts and repeated the test, checking with an electronic temperature probe. With 8 quarts, the end-of-test temperature was 167.5 degrees, while it was 170.2 degrees F with 4 quarts in the sump, a difference we don’t consider significant and certainly not one to suggest longer engine life by running a full sump. CHTs were identical for both tests. On the plus side, for long endurance flights, a full sump is an advantage to minimize running the sump dry.

Owner reports confirm that oil consumption is reduced when air/oil separators are used and that the aircraft underside will remain cleaner.However, as noted in the sidebar, not everyone gets good results. Our own results with the M-20 were lukewarm in this regard but other owners report dramatically cleaner bellies. Based on this, we think the claim of a cleaner airplane is generally realistic and if thats all you want, either product will help.

The downside of this, of course, is that using little or no oil between changes is not necessarily a good thing. If air/oil separators do concentrate acid and contaminants, not adding make-up oil between changes doesnt help, because the oils anti-wear and anti-corrosion additives arent being refreshed.

Our tests of oil moisture content and acidity from a sump equipped with an air/oil separator were inconclusive. We simply don’t know if concentrated contaminants are a wear and corrosion issue or not. Our gut feel is probably not.

If there’s any doubt, change the oil more frequently rather than less frequently. And if you don’t fly much, say under 50 hours a year, were wary of recommending an air/oil separator at all, for fear of concentrating moisture in the oil and aggravating an already difficult corrosion regime.

Our bottom line conclusion is this: If youre worried about a greasy belly, get the engines stock breather system in shape first, test the crankcase for pressurization and buy an air/oil separator only as a last resort. And change the oil frequently.

Also With This Article

“Checklist”

“Owner Reports: Success is Not Exactly Slam Dunk”

Contacts

Airwolf, 800-326-1534, www.airwolf.com

Beryl DShannon, 800-328-4629, www.beryldshannon.com

M-20 Turbos, 800-421-1316, www.m-20turbos.com

RAM Aircraft, 254-752-8381, www.ramaircraft.com

-Kim Santerre is editor of Light Plane Maintenance, Aviation Consumers sister publication.