Unless youre among the small but increasing number of aircraft owners lucky enough to own a jet, your airplane has at least one propeller and sooner or later, it will need an overhaul. The cynical joke among some mechanics and owners is no known prop shop ever saw a propeller that didnt need an overhaul.

While that may be too harsh, even cheapskate owners are finding that there are too many substandard props out there that are signed off as airworthy but are, in fact, marginally airworthy. No small number of them are absolute junk. Why? Corrosion, mainly, and lack of maintenance by owners who just don’t understand

what kind of care propellers typically need and whose ignorance costs them money. In fact, according to the pros, treating your propeller like the critical component it is and lending it a little TLC every now and then can go a long way toward preventing costly maintenance. And when your well-cared-for prop does go into the shop, you may have more options than just getting it overhauled.

The Usual Suspects

The typical propellers main enemy isn’t the wet-behind-the-ears private pilot who insists on using it to muscle the airplane in and out of the hangar. Its not even the guy who taxis over runway lights and into ditches while talking on a cell phone-more about him in a moment. Instead, according to the prop shop managers and manufacturers reps we spoke with, its aviations oldest bugaboo: corrosion. Look at just about any metal prop out on the flightline and you’ll probably find its leading edge is rough, with small pits and-if it hasnt been painted recently-some whitish discoloration. Thats corrosion, and its slowly eating away at the prop.

What about wooden props? While corrosion usually isn’t a problem with a wood prop, they can require re-torquing as frequently as every 25 hours, according to Sensenich Propeller Manufacturing Companys Ed Zercher. As temperature and humidity levels change, so does the props moisture content. As the prop expands and shrinks, the mounting bolts torque changes. Fly a wooden prop from a cool, dry area to a warm, humid one and it likely will need attention once you arrive, Zercher told us. As a rule, wooden props are less efficient than metal ones, he added, since the airfoils at the tips cant be made as thin as with metal and still retain the necessary strength.

A metal props other main enemy is the nicks and gouges picked up in normal operation. Along with the pitting from corrosion, these create stress risers, weakening the blade. Stress risers can lead to cracked blades. In extreme cases, part of the blade can break off in flight, creating a severe out-of-balance condition. These incidents crop up occasionally in our routine review of NTSB and FAA accident and incident reports. We wouldnt call them widespread, but they arent rare, either. If you catch a blade departure quickly enough and reduce power or shut off the engine altogether, the engine might not shake itself to pieces and

the prop might stay on. Either way, youre going to get some real-world engine-out practice and probably pay for an engine teardown.

In extreme cases, the prop simply departs the aircraft. Were aware of two recent incidents-one involving a Piper Malibu and the other a Beech Bonanza-in which propellers departed the crankshaft. The Malibu landed without further damage, but the Bonanza wasnt as lucky. But neither event involved injuries. And at this writing, neither prop has been found. Prop loss is not a trivial event. In some cases, it can alter the aircraft CG enough to render it uncontrollable.

Are such calamities avoidable by routine inspection? Maybe yes, maybe no. But you wont find potentially catastrophic damage unless you look for it, including damage that wasnt evident the last time you flew the airplane. Your IA will smooth the lesser nicks and gouges at the annual inspection. Larger ones are problematic: The temptation is to smooth them out, too, but they might be large enough to condemn the blade. To make the call, the prop manufacturers literature must be consulted. You shouldnt be surprised to learn that your mechanic doesnt have your props maintenance and overhaul manual. Welcome to the real world.

Enter The Prop Shop

“How many pilots know their props specs?” New England Propellers Ron Porciello asked us. The answer, of course, is very few. “Whether its pilots, mechanics or both, whether its the FAAs fault or not, no one out there knows a damn thing about props.” Thats one reason propeller shops exist and why-like businesses

overhauling engines or refurbishing paint and interiors-they can specialize.

Some prop-related specs are available to owners. For example, check your airplanes type certificate data sheet (TCDS) for maximum and minimum diameter specifications, plus pitch settings for a constant-speed model. If your airplane/prop combination is fixed-pitch, the TCDS also will include static RPM limits. Other specs, like minimum blade width, static balance and the like can only be found in the prop manufacturers literature. Few owners have gone to the trouble to obtain that material and even their mechanics usually defer to the local prop shop.

With fixed-pitch props, the shops main concerns include diameter and pitch. Prop manufacturers specify minimum diameters for their various models and the engines on which theyre mounted. As noted above, see the aircrafts TCDS for static RPM and minimum/maximum diameter limits. Stripping the old paint, cleaning up corrosion and repainting usually is all a fixed-pitch metal prop needs.

It gets more complicated with a constant-speed, full-feathering or reversible prop and thats where prop shops earn their money, according to McCauleys Gary Peak, who says one of his companys greatest challenges is conveying to the field the proper techniques to use in propeller maintenance. Like other major manufacturers, McCauley recommends a full overhaul no less frequently than every 72 months. Yeah, sure. Part 91 operators rarely comply with that recommendation, usually waiting until engine overhaul or prop malfunction before shipping the thing off to the shop.

But Peak contends that ignoring or postponing recommended maintenance is a classic pay-me-now-or-pay-me-later situation. Yoo Crisp at H&H Propellers in Burlington, N.C., agrees, noting that the average clean-and-seal job on a two- or three-blade prop costs between $700 and $900. Add a couple of hundred if seals or other parts are needed. Thats for a properly functioning prop. An overhaul can easily add up to the mid-teens before any parts are added to the cost.

Were aware of an older three-blade McCauley that went into the H&H shop for an overhaul. The cost of the basic work was in the $1500 to $2000 range, but the total tab was closer to $5000 since the prop needed new ferrules due to-you guessed it-corrosion. That might have been avoided with a $900 clean and seal halfway to the 72-month overhaul period.

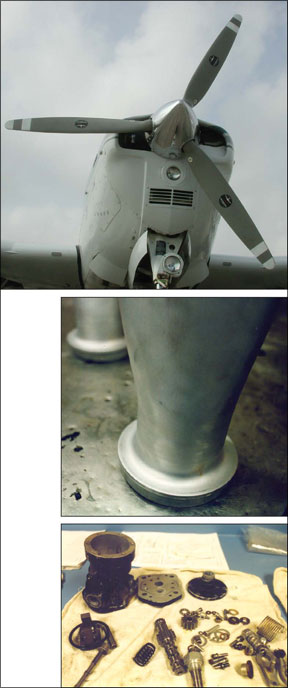

OVERHAUL SPECS

How does an overhaul differ from a clean and seal or an inspect and repair as necessary (IRAN)? For one, an overhaul entails complete disassembly and reassembly, using new O-rings, seals and lubricants. McCauley recommends the hub and blades be stripped to bare metal and a magnetic particle inspection performed to reveal cracks. Wear items, including blades, are measured to ensure theyre within limits. The blades airfoils are dressed to specs, while required width and thickness is assured. Finally, the various components are replated or repainted, as required. Once everything is reassembled, blade tracking is checked. At most

shops, all of that occurs in about a week, maybe longer if new parts are necessary.

Meanwhile, a clean-and-seal job is just that: The prop is flushed internally, lubricated with new grease or oil and re-sealed. Somewhere in the middle is the IRAN, which doesnt yield a prop overhauled to new specs, but does clean up corrosion and usually results in fresh paint. In fact, an IRAN can be as inexpensive or elaborate as the owner wants. The major difference between it and an overhaul is that an IRAN doesnt result in a prop rebuilt to new limits and its TBO counter isn’t reset to zero.

Keeping your prop happy between visits to the prop shop is just common sense operational technique. Keep it clean and free of corrosion with an oily rag and have a competent technician smooth out any nicks or pitting. Keep it painted. If you insist on polished prop blades, you’ll be out at the hangar quite often, keeping corrosion away.

Pay attention when taxiing and during other ground operations, too. “If people knew how to fly and knew how to taxi, wed be out of work,” says Porciello. Based on prop strikes alone, owning a prop shop is a “wonderful business,” he adds, since his shop sees three or four of them a week.

And no aircraft type is immune: “We see Aerostars and Piper Cubs getting involved in prop strikes,” Porciello says. H&H Propellers Crisp agrees: “We had one guy in a twin who was trying to taxi and talk on his cell phone at the same time. He needed two new props, plus engine work.”

Typically, according to Ed Zercher at Sensenich, most pilots suffering a prop strike report it and follow up with their mechanic. It can get expensive, with the average cost of a prop strike involving a fixed-pitch prop costing about $3000, according to Porciello. A constant-speed version is more problematic, Porciello adds, since a new three-blade prop can cost $10,000 to $12,000.

He says Hartzells specs require scrapping the hub after a prop strike if a damaged blade cant be made airworthy. Somewhere between those extremes is where the bill for the average prop strike will come in.

Overhaul or New?

Both McCauley and Hartzell, but especially Hartzell, have recently been aggressive in offering favorable pricing on replacing run-out two-blade props with new, three-blade models. The roots of this sales policy date to the early 1980s, when both companies were hustling to replace sales lost during the big GA downturn. Further, both companies also know what prop shops know: There are enough junk props flying around to represent a significant liability tail. Selling customers new props reduces that and makes good business sense.

Prices on new props vary widely by aircraft type. In some cases, for the same airplane, the new three-blade will be cheaper than the two-blade original, but in most instances, the three-blade is now more expensive. Because new props are expensive, overhauls remain competitive, provided that the hub or blades are within service limits. If both hub and blades are shot, the economics will favor a new prop. If the hub is serviceable and the blades arent, or vice versa, an overhaul is usually the best-value choice.

Typical prop overhauls come to under $3000 and with new props starting at around $6000 or so, the overhaul just looks better. At one time, Hartzells were cheaper to buy but more expensive to overhaul than a McCauley. Thats no longer true because McCauley has raised its blade prices such that if you need just one, its cheaper to buy a set and keep one as a spare.

Prop Shop Options

Should Part 91 operators adhere to the manufacturers overhaul recommendations no less frequently than every 72 months, even if its not required? Maybe. Its tough to accept the downtime and expense of sending out what appears to be a perfectly good prop. But if youre ignoring manufacturer and shop recommendations to keep it clean, well-oiled and painted, youre likely allowing corrosion to eat away at your props TBO.

Certainly an IRAN would be in order; asking for an overhaul might cut down on the phone calls and could speed up the shops turnaround time. If the props in sad shape (something your mechanic should know) or its been several years since its seen the shop (something you should know), opt for the overhaul.

What about a clean and seal? If the airplane is going to be down anyway-like for a top overhaul or other lengthy work-getting your local prop shop to take a look is a good idea. you’ll have to pay for removal and installation, but most shops pick up and deliver for free. When everything gets back together and flying in close formation again, you’ll sleep better knowing it was looked at.

As for choosing a prop shop, the choice is almost always ruled by geography. Traditionally, prop shops serve regional areas and most offer shipping and pick-up services. Shipping fully assembled props long distances is feasible and it is done, but given the choice, its more practical to deal with the local shop, providing its reputation is good. If you trust your mechanic, you can reasonably trust his judgment on prop shop selection, too, since hes no more interested in a comeback overhaul than you are.

Jeb Burnside is an

Aviation Consumer associate editor of edtior-in-chief of Aviation Safety magazine.