With primary EFIS hardware prices at an all-time low, you’d think the decision to not repair old iron gyros and static instruments would be easy. It’s not. That’s because budget systems like a pair of Garmin G5s and Aspen’s entry-level E5 PFD could still run north of $10,000 after installation. That’s still out of the budget for many.

The fallback, of course, is repairing/overhauling old instruments that may be left over from the Reagan era. This may or may not make sense, depending on the supportability, reliability and bottom-line cost for the work. In this article we’ll look at the market for instrument repairs and exchanges, while offering tips for deciding whether an EFIS upgrade is the better decision.

Where Should You Go?

When faced with any instrument problem, most owners leave it up to an avionics shop or even their mechanic/repair shop to handle the repair-from removal to reinstallation. We think the owner should be more involved in the process. There are more considerations than you might think, and there’s more to instrument repairs than the physical bench work.

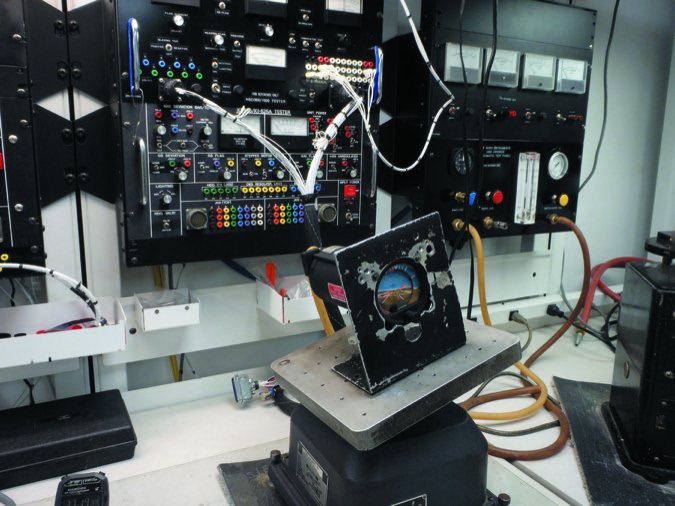

Aside from troubleshooting and verifying that the failure is contained to the instrument (there could be a pitot/static system problem or issues with the vacuum system), whoever is handling the repair will have to decide where to send the instrument. That’s because the typical avionics shop won’t have instrument bench repair capabilities, and the repair will be farmed out to a qualified (hopefully) instrument facility. These instrument shops should have the qualifications to accurately represent the work per the regulations. It’s easy to trick up the wording when it comes to rebuilding and overhauling.

FAR 43.2 says, in part, that no person may describe in any required maintenance entry or form a component being rebuilt unless it has been disassembled, cleaned, inspected, repaired as necessary, reassembled and tested to the same tolerances and limits as a new item, using either new parts or used parts that conform to new part tolerances and limits. To sign a component off as being overhauled, nearly all of the above applies, except testing it to new part tolerances. That might not always happen.

For example, properly overhauling a gyro includes replacing the bearings and any worn mechanical parts. It also includes disassembling the rotor assembly, while replacing any worn parts in it. Autopilot interfaces make the entire process more complex, often requiring additional work when the instrument is reinstalled because it should also include calibrating the electronic outputs.

In the case of many autopilot gyros, you’ll pay additional shop labor because there might be fine adjustments for the proper autopilot bank angles, roll rates and flight director command bar presentation. Performing this alignment could be the difference between an autopilot that flies perfectly or one that’s sloppy. It may even require flight testing to make sure the adjustments are correct.

The Wild West

That’s how some describe the instrument repair and overhaul business because, frankly, some shops have no business attempting repairs for lack of current manuals and approved service parts. Plus, a simple repair may only be a temporary fix, and performing a zero-time teardown overhaul may be money better spent on the front end. That’s often the case for air-driven instruments.

“For these instruments it’s usually not economical to simply replace a couple of the gimble bearings, given the level of teardown that’s required to gain access. We feel we’re not providing the customer a good service by charging them for half of an overhaul when we just don’t know how long the rotor might last,” said one instrument shop manager.

David Copeland at Mid-Continent Instruments and Avionics (which has locations in Kansas and in California) told us that the majority of instruments it reworks and sells are completely overhauled. “Sometimes that’s a problem for the customer because the overhauled instrument aesthetically looks better than any of the other instruments in the panel,” he said, tongue in cheek. Quality shops like Mid-Continent might send out fresh instruments with new glass and repainted bezels and casings, for example.

The other thing to consider is the instrument’s warranty, which may tell a lot about the quality of the overhaul. Typically, a repair is covered for 90 days and only includes the work performed during the repair. The standard instrument overhaul warranty is generally one year. You could spend $150 on a basic repair today, but might ultimately have to pay for a $500 overhaul next week, for example. That’s why for basic instruments, we think an overhaul makes the most sense-especially while the instrument is opened up. But not every instrument may be eligible for overhaul. Its vintage and version may have obsolete parts. This is problematic if you’re trying to get back in the air in short order. Mid-Continent’s Copeland told us that the typical turnaround time may be five to 12 days, but an exchange will obviously be a lot quicker and oftentimes the best option if you don’t care about getting your specific instrument back. There are a few snags many don’t think about.

It’s important to note that even if your instrument is still supported, it might not be eligible for an overhaul or exchange. If the instrument is missing a data identification tag (listing the original part number and serial number), you could get stuck with buying a new instrument outright. Similarly, if the removed core is found to have excessive corrosion or damage, it will likely be rejected as an acceptable core.

Obsolete Instruments

In some cases the instrument may simply be too old to do anything with, and this includes vintage attitude instruments and altimeters. This means you’ll probably have to buy an outright factory new replacement, with no core credit offered.

There are options. Two industry-standard brands-Sigma Tek and United Instruments-were suggested by every shop we spoke with. If you’re faced with replacing an old obsolete airspeed indicator, you’ll likely have to order a new United model and rest the old one on your bar shelf as a conversation piece. Several shops told us there’s no support for some original-equipment Piper and Beech models. The shop needs the airspeed range marking data from the aircraft flight manual to set up the new instrument appropriately.

As for gyros, Sigma Tek offers a variety of replacements, including models with vacuum warning flags, internal lighting and heading reminder bugs for directional gyros. The company also offers models that will drive the heading command function on autopilots.

Speaking of autopilots, there might be more interface to your system than you realize, and the vintage round-gauge instrument you want to ditch in favor of a newer model might have to stay because it’s integral to the interface. Some autopilot altitude preselect systems, including models from S-TEC, BendixKing and Sperry, rely on the encoding altimeter for a baro source input. Even the turn coordinator could still be required, since it drives most Genesys/S-TEC rate-based autopilots. The same goes for the BendixKing KAP140 system. For the majority of buyers, this isn’t a deal breaker, but it complicates new panel layouts and won’t alleviate the high cost of instrument maintenance-a driving factor for upgrading in the first place.

Some stuff might finally be retired. This includes just about anything made by Narco Avionics, including the DGO-series HSI. But others, like the King KCS55A slaved compass system with HSI, may be worth saving, but get ready for a big invoice, and some troubleshooting along the way. We get lots of calls here at the magazine from readers looking for troubleshooting advice for this system, especially when they take it to shops that aren’t experienced in working on the system. It’s complex.

Consider that troubleshooting basic gyro instruments is easy-if it tumbles or is slow to erect it’s probably time for overhaul. But diagnosing the multi-piece Bendix King KCS55A slaved HSI system isn’t. We’ve seen many a hasty shotgun approach to component replacement cost owners thousands of dollars, and in some cases not even fixing the original problem.

You might start the repair process by understanding the system and doing some basic troubleshooting of your own before you show up at the repair shop. The venerable KCS55A is generally a reliable system, but as the fleet of KCS systems age, shops are seeing more subtle failures that can be difficult to accurately diagnose. It’s a challenge because there are four major remote components in this system, including the KI525A HSI, the KG102 remote heading gyro, the KMT112 magnetic flux sensor and KA51 slaving accessory.

A common failure mode might include heading error, where the system doesn’t accurately keep up, despite the built-in slaving circuitry that’s designed to correct for natural gyro precession. It’s natural to assume the problem exists in the remote gyro, and it often does, but there could be a problem in the HSI itself, perhaps binding in the gears that drive the heading card. An experienced shop should ask you some basic operational questions. Does the system fail while in free-gyro mode or only in slaved mode? To find out, select the free gyro mode on the panel-mounted slaving control. You’ll need to correct for some gyro precession by slewing the system to the proper heading, just as you would with a conventional directional gyro. When the system is showing a heading error, is the heading flag in view? You’ll want to be armed with the answers to these questions before showing up at the shop-especially the wrong shop-which might shotgun expensive components without doing the right troubleshooting.

The Extras That Add Up

Don’t underestimate the cost of shipping when your shop farms out an instrument repair. Fragile gyroscopes need to be shipped in larger containers to keep them safe during transport. The resulting costs can add hundreds of dollars to even basic instrument maintenance. If you’re in a hurry to get the instrument out and back, freight costs can be shocking. Labor costs can be hefty, and some aircraft are simply easier to work on than others.

Reader Jim Simpson told us of the labor effort his shop billed out for removal and reinstallation of the BendixKing KI256 flight director gyro in his Cessna P210. “In addition to the $2388 flat-rate overhaul cost of the gyro, the invoice included $183 in freight (to and from the instrument shop) and $990 in labor,” he told us. When he questioned the shop about the charges he was told it took nearly two hours to disassemble and reassemble the panel, and the rest was nulling the gyro’s outputs to properly drive the KFC200 autopilot that it’s connected to. This included roll and pitch adjustments, plus adjustments to the command bar presentation. “Had I known I would be into this old thing for close to $4000, I would have considered a glass upgrade,” he told us.

Another gotcha could be hiding inside the case of an encoding altimeter. These are altimeters that also house a Mode C altitude reporter. Our advice is to pay particular attention to the health of these instruments during the two-year pitot/static/transponder certification. In for an ADS-B upgrade? Have the shop evaluate the altimeter’s health.

You might even consider replacing the instrument altogether. That’s because the cost of overhauling or replacing a standard altimeter could be half the price of a combination unit. To reduce these maintenance costs, you’ll have to spend some money up front. The installation of a new altitude encoder might cost $400, in addition to the cost of a new United altimeter that averages around $1000.

Plus, if the altitude encoder inside the altimeter fails, the shop won’t be able to sign off the altimeter portion during the two-year inspection because the regs suggest that all of the instrument must be functional, not just a portion of it.

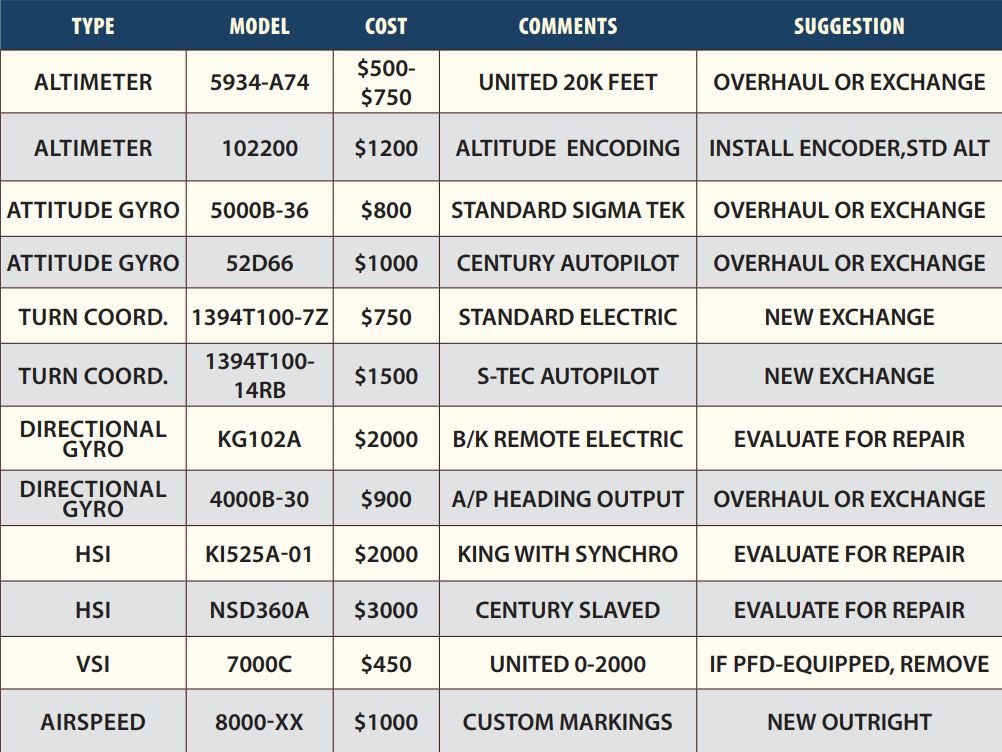

A Lukewarm Case For Glass Upgrades

The pricing chart above supports the idea that you should at least get a couple of quotes for a primary flight display (PFD) when faced with an instrument overhaul. As we’ve been reporting, entry-level systems from Garmin (the G5 AI and G5 DG) and Aspen (the Evolution E5 PFD) are priced around $5000, but the retrofit will likely top $10,000 after installation. That’s better than $20,000, which is where the numbers fell before Garmin and Aspen brought non-TSO solutions to the market. But not all potential buyers are sold on $10,000 glass upgrades.

In a recent survey on sister publication AVweb, 34 percent of respondents said they would at least get a proposal for a budget glass upgrade, 27 percent thought that a $10,000 EFIS buy-in was overpriced, 29 percent thought the price was fair given the capability and 10 percent said they weren’t even installing ADS-B.

That pretty much jibes with what shops told us, reiterating that many buyers faced with instrument repairs (not necessarily those who would spend a lot more for high-end upgrades) are interested in a Garmin G5 or Aspen E5, but a good percentage end up keeping legacy instruments, at least for the short term.

David Copeland at Mid-Continent sees that exact trend and as a result, the company is stepping up its efforts to source more core units so it has a larger supply of instruments on hand and ready to ship. Mid-Continent supports over 6000 models of instruments and avionics, including autopilot servos.

“Over the past 18 to 24 months, we’ve seen a resurgence in aircraft owners deciding to keep their legacy instruments rather than upgrading to full-up EFIS because of the other expenses that tag along with aircraft ownership,” Copeland said. That could make sense. But in our view, if a vacuum DG fails, the $1000 or so it takes to get it overhauled is far easier to swallow than $10,000.

“An Aspen glass upgrade isn’t in my immediate future because I dropped $60,000 on a new engine,” one airport neighbor recently told us. He decided to have his failed attitude gyro and aging DG overhauled instead of making the switch to a more reliable solid-state display and ditching the vacuum system in favor of going all electric.

For certain, the instrument repair and overhaul business isn’t going away any time soon. Copeland points out that there are hundreds of thousands of aircraft in the field still equipped with legacy instruments and they simply need to be supported.

On the other hand, the support network for doing so has certainly shrunk over the past few years. A lot of smaller instrument shops have gone out of business, leaving fewer options for getting legacy instruments repaired. Even some manufacturers are scaling back their support network. BendixKing curtailed its dealer network and only sells service parts to four facilities around the country.

Our advice is this: If you have a legacy instrument that needs to repaired, it’s time to do some math. First, ask your shop where it plans to source the replacement (or repair), ask if it’s a full teardown overhaul and what is the length and terms of the warranty. Then, get a couple of proposals for an EFIS replacement, weighing the benefits of going with all-electric, solid-state technology. For some the benefits will be compelling, for others, not so much.

Typical Overhaul Costs and Recommendations