Doctors learn that a certain bedside manner is helpful when conveying bad news to a patient. Airplane mechanics-at least the ones we know-don’t necessarily feel the same obligation, thus when catastrophe looms large during an annual inspection, you might hear, “Hey, we found a crack in your case, youre hosed.” The medical analogy is apt, for a cracked case is the equivalent of plugged arteries; surgery isn’t just an option, its a must. In most cases, a cracked case will ground the airplane and an overhaul will follow. No matter how much time is on the engine, splitting the case to fix a crack and reassembling it makes little sense. A full overhaul or reman is the way to go. But it can be a little tricky economically. Shops have been weld-repairing cases for years, with good results. If the repair is done correctly, the case might not be as good as new, but it will probably remain serviceable through another TBO run. If the case isn’t repairable or its marginal, the decision may not be so black and white. On four-cylinder Lycomings, for instance, buying a new case may be at least plausibly affordable. On six- cylinder engines of any size or type, it probably wont be. We think any owner confronted by a cracked crankcase should sit down with a clean pad and a sharp pencil and compare costs carefully. In most cases, welding the case is the no-brainer option.

Tiny Industry

The case welding business isn’t what it used to be. There are now only a handful of shops doing this specialized work and we recently visited two of them, both in Tulsa, Oklahoma, within walking distance of each other. The shops are vastly different in size and personnel, but they both put out impressive repair volume and are respected in the industry.

Of all of the businesses that repair cases, four are located in Tulsa, three of them just a few hundred feet apart on Sheridan Road. Two others are ECI in San Antonio, Texas, and Nicksons Machine Shop in Santa Maria, California. Teledyne Continental does case repairs as well, although it used to farm out this work to the Sheridan Road shops.

What owners need to understand about case repairs is that the process is more involved than just grinding out the cracked metal, building it up with welding and

smoothing it over with a grinder. If the case isn’t machined correctly after the repair, the heat of welding can distort it beyond practical use. Thats because the crankcase is an aluminum casting that supports the crankshaft and camshaft internally and to which cylinders and all the rear-mounted accessories are mounted. The sump is usually cast aluminum on a Lycoming, stamped steel on a Continental and the accessory case is cast for both types.

Cases are cast in two halves bolted together along a carefully machined mating surface. If you think of an engine case as an English walnut shell, you’ll get the picture. Physically, a case has to be light, so cases are thick where machined surfaces, connecting hardware, studs, through bolts and mounting pads are located. Internal and external ribs stiffen the shell where loads are greatest, but where loads are less, the case may be as thin as 1/8th inch. All crankcases are susceptible to damage of various kinds.

Lower horsepower cases have lower loads to contend with, which is why some four-cylinder Lycomings of 160 HP or less don’t suffer much cracking. And if they do, the cracks are almost invisible in the ribs between cylinders or on the lower front sides where the starter and alternator are mounted. A common crack is from the forward lower stud on the number 2 cylinder that could propagate backwards above the oil return tubes. A few of these engines and the 180- to 200-HP engines will develop the occasional “smile crack” under the number 2 cylinder.

Six-cylinder engines are another matter. Larger Lycomings usually present at the upper front corner of the number 6 jug and around the oil filler tube. These larger engines create stress areas through torsionals in the engine itself and between the airframe and engine. The sheer number of combustion events probably aggravates this. In Continental engines, the most prevalent crack emanates from a cylinder stud. On the O-470 and O-520 engines, sandcast cases are less prone to cracks than later Permold cases with front mounted alternators. Changes in the case design, such as the humpback Phase III castings and the Phase IV products with the seventh cylinder stud seem to crack less, but that doesnt mean they don’t crack. An interesting consensus of the shops we interviewed is that the older narrow-deck cases are better than all but the very latest versions, so if youre looking for a replacement case on the used market, don’t be afraid of an older one thats in serviceable shape.

How Bad is Bad?

Some years ago, Lycoming and Continental published inspection criteria for crankcase halves. These specs outlined critical and non-critical areas for specific engines and actually based some repairs on sheet metal methods, recommending stop drilling cracks, for instance.

There are a number of areas where a crack merely weeps a bit of oil and will be fine as long as its monitored. However, most mechanics will opt to take the engine out of service and have the case inspected and repaired if they detect a crack. Besides cracking, there are other sorts of damage that need to be reckoned with, too.

Assembly damage:

A mechanic with a dirty shop or an ill-considered assembly routine can damage a case. A common problem is mechanics using more silk thread than required to seal the case halves. By running a second thread or encircling bolt or stud holes, the additional thickness spoils torque readings and can lead to fretting which will have to be machined off at the next overhaul. If its bad enough, it can render a case unserviceable.Disassembly damage:

To split a case correctly, a case splitting tool or a jack screw is required to demate the case halves. A screwdriver or putty knife and hammer damages the mating surfaces and that damage must be welded and machined. Cases have been cracked using the wrong tools.Cracks:

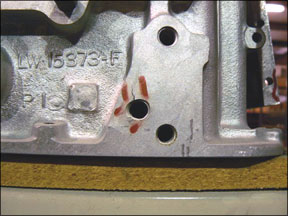

Vibration, aggravated by the loss of proper torque through bad assembly or simply as a function of the design, causes cracks in cases. Some older designs had either too little material to absorb stress or sharp bends that create stress risers. Cracks are the number one reason cases are sent off to be overhauled or repaired and most cases crack in the same predictable spots.Stud and through bolt damage:

Improper torque or using incorrect nuts or tools can damage studs. Occasionally, a stud will break off in the case if vibration or stress become too high.Corrosion Damage:

An engine not flown much or maintained poorly may corrode externally in areas where the paint has been allowed to thin or disappear altogether. Usually, this is surface corrosion and can be ground off with a rotary sanding disc, primed and painted.Catastrophic Damage:

When cylinders and rods become shrapnel, a new case is the least of your worries. Sometimes, the sump, accessory case and either case half may be salvageable. Or not. An engine compartment fire will often tank a case. It may look undamaged, but aluminum cant withstand much heat and still retain its strength.Fixing It

If a crack is suspected, the area has to be steam cleaned and bead blasted to bare metal and if a line is still indiscernible, a dye penetrant such as Zyglo or a Magnaflux inspection will be employed. If a crack is suspected, the shop might remove some material with a sanding disk to reveal an oil infused crack. The crack is then ground without penetrating the case. If this must be done, its done from the inside of the case.

The welder will build up material in the crack and also weld up the gear bosses on the back of the case and later, the halves will be machined, line bored and/or honed, cam bored and the gear bosses will either be machined or drilled and bushed to keep the accessory gears located correctly. The post-weld machining is by far the major player in repaired case quality. If it isn’t done right, the case halves and all the innards wont fit correctly and this can lead to myriad problems.

Interestingly, the FAA has no specific criteria for welding cases. Rather, each shop is directed to use its expertise and experience to determine the reparability of a case and do whats necessary to make it airworthy. The FAA requires only that the shop complete the work according to its approved manual, which is different from shop to shop. A shop whose management is ultra-conservative may pass on a repair that another shop might be perfectly happy to fix.

DivCo, for example, wont repair a case thats been repaired two or three times previously, or if the case halves have been previously machined more than .015 in. Nicksons Machine Shop does only inspection/repair/recert on a shop-rate basis, foregoing the flat rate pricing used by most other shops. Owner Dennis Leal tells us that aircraft engines are only a part of Nicksons business and that they were the first shop to be given a repair station certificate for weld repairs in 1966.

How Good?

Welded cases are returned to service with a yellow tag that establishes airworthiness. But is a welded case as good as new? Probably not, but it doesnt affect overhaul warranties. Welded case or not, standard warranties apply. The shops we interviewed report few warranty problems with repaired cases. They unanimously agree that a welded area doesnt develop the same crack again. True, the stresses may be shifted to a different part of the case which may subsequently crack, but this happens in improved OEM cases, too.

The clincher for the integrity of a repaired case is that every shop we talked to-both weld shops and overhaul facilities-have no qualms about recommending weld-repaired cases and flying behind them with no reservations.

Repair Costs

Compared with buying a new or even a serviceable case, weld repair costs are chump change. For example, most shops inspect, weld and recertify a small-displacement Lycoming or Continental for around $700 to $800.

Larger cases naturally cost more and Continentals are generally less expensive than comparable Lycomings. One chooses a repair shop based on experience, price and reputation, but mostly on what the overhaul shop recommends. After all, the overhaul shop has to stand behind the engine and its not in their interest to save a few bucks by buying a shoddy case repair.

If the case has crummy machining, it wont mate correctly and may start leaking oil in mere hours. Or, if the deck dimensions are wrong, the crankshaft might be squeezed too tightly and the engine wont turn over.

General industry practice is to quote an overhaul based on a serviceable crankcase, serviceable meaning it might have cracks or need repairs for which there wont be an upcharge. But ask the overhaul shop about this before committing. Policies may vary. If the case isn’t repairable, brace yourself for a big upcharge. (See the table on page 13 for some examples.)

The two engine manufacturers play an interesting game with regard to core charges on cases. Distributors tell us that Lycoming, for instance, reserves the right to decline core value to an owner exchanging a run out for a reman or pool overhaul. But if the case isn’t disassembled and isn’t obviously damaged, the company tends to honor the core charge even if the case is cracked. Continental, which does its own case repairs, seems to follow a similar policy.

Either way, when collecting engine quotes, ask the shop about its upcharge policy with regard to cases requiring repairs. If youre dealing with a distributor on a rebuild or a new engine, ask the distributor about experience with the two majors on core charges. You may hear a different story than we have and the latest data is usually the best data on core policies. The stated policy may very we’ll be different from what the factory actually does.

Jim Cavanagh is a frequent

Aviation Consumer contributor. He lives in Kingsville, Missouri.