As we predicted a few years ago, the FAA’s ADS-B equipage mandate is starting to create a scheduling backlog at many avionics shops. This won’t lighten up and if you haven’t equipped and plan to fly in ADS-B airspace, now is the time to get on a shop’s schedule to at least plan the interface.

But if you don’t have a relationship with an avionics shop you trust, selecting a good one is more involved than just scheduling. In this article we’ll focus on some of the traits you should look for when qualifying a shop to do your avionics work. That’s everything from ADS-B mods to major panel upgrades and repairs.

Capabilities

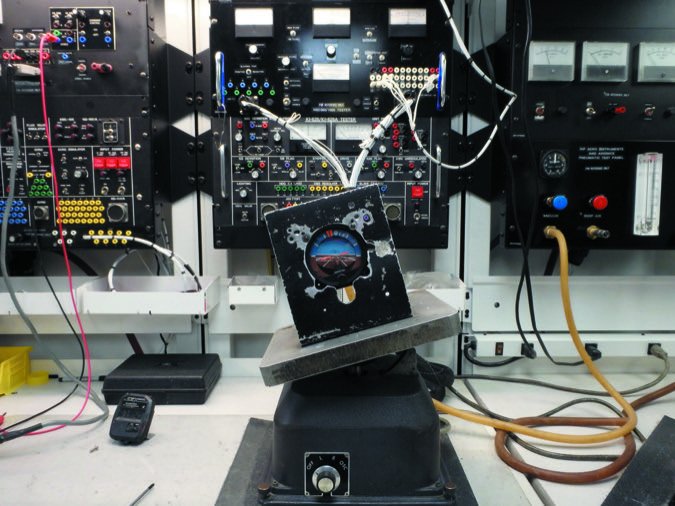

In our estimation, a lot of the smaller avionics shops have gone away over the past few years simply because they didn’t have the competitive edge and the broad capabilities of larger ones. And by larger ones we mean shops that have a diverse staff, modern test equipment, bench repair capabilities, plus maintain dealerships for major brands.

You’ll find that the majority of established avionics shops are Part 145 FAA repair stations, but some might have varying ops specs. For example, some might have instrument repair and overhaul capability, plus are spec’d to work on ship’s weather radar, to name two major fields of expertise. One benefit of using a shop that maintains a Part 145 repair station is that it’s required to have a quality control program in place (including an approved quality control manual), an area in which the FAA has placed sizable emphasis mostly for the right reasons.

Since the nature of modern avionics means deep interfaces with both the airframe and the engine, you should ask if the shop has experience working on your aircraft model. For example, if the installation requires adding or modifying antennas and your aircraft is composite or fabric (as opposed to metal), consider this specialty work that requires special skills. Not all shops can hang a new antenna on a Cirrus.

If the job includes adding an engine monitoring system with fuel totalizer, the shop will be installing temperature probes on the engine and working with the fuel delivery system. Ask if it has staff members who hold A&P certificates and are skilled with performing engine and fuel system mods. Some avionics shops might farm out this portion of the job to a maintenance shop-which is fine-but you should know who is doing the work and final testing.

Where it works should be a major consideration in choosing a shop. We’ve seen some small shops that don’t have access to hangar space, but instead work outside on the ramp-clearly not the best approach. On the other hand, if the shop works in a community hangar where hangar pulls are done a few times a day, hangar rash is a real possibility. We know of some otherwise nice hangars infested with birds and you know what that means. Ask to see the shop’s workspace because it will provide clues to how your airplane will be cared for. Ask the shop if it carries hangar-keeper’s insurance. Speaking of clues, one way to tell if a shop is organized is the manner in which it stores removed components. If you see interior pieces and removed avionics spread out on the floor around the airplane (instead of neatly organized on storage carts or shelves), it could reflect on the quality of the shop’s work.

Ask to see a job in progress and make note of how the technicians are working. We cringe when we see tools sitting on unprotected seats and on the wings. To cover its hide, many shops will do a walk-around inspection of the aircraft to make note of paint scratches and interior flaws.

Training and Flight Testing

Those who work on the shop level understand loud and clear that major avionics installations are not finished until the aircraft is flight tested. But don’t assume the shop will have flown the aircraft before you show up to bring it home. Some shops do have the qualified staff for flight testing, but they likely aren’t efficient and current in every aircraft that shows up on the ramp. Ask if your aircraft will be flown, by whom and if the shop or pilot has the appropriate insurance to do so.

Don’t assume that the aircraft will be ready to fly home once it’s flight tested. It’s not uncommon for there to be further tweaking that’s required after the flight test. For that reason (and for regular support) we suggest working with a local shop within reasonable driving distance whenever it’s possible because you could be making several visits during the project.

When deciding which shop will get the job, consider its approach to helping you learn how to use the new equipment. While avionics shops certainly are not in the flight training business (although some do employ flight instructors), ask how it can help tame the learning curve that tags along with modern equipment. Experienced shops know that you could be picking up a very different aircraft once the retrofit is completed. Cathy Rudd at Treasure Coast Avionics in Fort Pierce, Florida, stresses to her customers that they should be using all of the resources available to them while waiting for the aircraft to be finished.

“Once the new equipment comes in, we’ll give a customer the pilot’s guides as homework while they wait, plus we introduce them to any free tablet-based trainers that exist,” Rudd told us. We think that’s the right approach because fumbling through the operation of new equipment during the flight testing part of the job is not what you want to be doing. Remember, the technician sitting shotgun on the flight is not tasked to give instruction. He or she will be sitting up straight in the seat on this flight, watching your every move.

As Rudd pointed out, many of the manufacturer-provided tablet- and smartphone-based simulators mimic the real equipment, made more realistic because of touchscreen interfaces. We’ve used the ones from Garmin (for the GTN series navigators) and from Avidyne (for the IFD series navigators) and found them to be a good learning resource when used in conjunction with pilot’s guides. But those aren’t the only resources.

“There are a lot of good YouTube-based training/tutorial videos that we direct our customers to,” Rudd noted.

Rudd at Treasure Coast also takes the guidance one step further and often connects a new or potential customer with one who already has similar equipment installed. If you can go flying with someone who has the equipment, you’ll have a better idea if this equipment is for you. Ask the shop for customer references. Ones with happy customers will have no problem making the introduction.

Proposals and Payment

Successful shops are the ones that nail price quotes before tearing into the aircraft. One sure way to agitate a customer is to hit him or her with major cost overruns halfway through the job. But the customer needs to step up and bring the aircraft to the shop for inspection before committing to the work. Emailing photos of the panel is a good way to get ballpark cost estimates, but the only way for a shop to make an accurate proposal is by inspecting the wiring and other systems (including antennas and circuit breakers) before preparing the quote.

Still, there are just some things a shop can’t predict until the job gets rolling and it’s fair to accept there could be some minor cost overruns. Ask what potential gotchas the shop might encounter. Experienced shops can pretty much tell what they’ll be getting into when they inspect the aircraft and also look through the maintenance logbooks. They’ll generally price a job with these snags in mind. For that reason, a price quote that’s substantially lower than others (you should get at least three proposals for the same scope of work) should be a red flag.

Worth mentioning is payment terms. These are generally clearly spelled out on the proposal. If they aren’t, ask the shop what it expects from you. It’s just bad business for a shop to hand an aircraft back to the owner without first getting paid and good shops understand this.

As one shop manager who asked not to be identified described, time-consuming and costly payment disputes can be completely avoided if the shop spells out the terms and the customer follows them.

“I’ve been bitten one too many times by core customers who left on a handshake, promising they would mail me a check after they collected from their partner or after they moved some money. I ended up in court and won every case because I had terms in writing,” he told us. Truth be told when it comes to getting paid, mechanics have sizable amounts of ammunition when the aircraft is in their possession, but once they let the aircraft go, it will take a trip to court to legally collect a debt. In general, the party that has possession of the aircraft has the advantage, but not always. We say do the right thing and pay the bill before leaving.

What are fair terms for the typical major avionics retrofit? It’s not uncommon for shops to require half of the project cost when the job commences and the full balance at delivery. Understand that of all the challenges associated with running a shop, keeping on top of cash flow is the most difficult, especially at smaller shops. Think in terms of retrieving your vehicle from a dealer after repair. You won’t get your keys back without paying the bill, and there’s no saying it will be fixed. At least with an aircraft you might be able to flight test it to be sure it all works. Most shops warranty the wiring and workmanship indefinitely, but it’s worth asking what’s covered and for how long.

Be Straight

Customers don’t like surprises, but neither do shops. Here’s a scenario: You’ve made a deal to have a Garmin GPS installed, which connects directly with an existing analog HSI and autopilot. For as long as you remember, the autopilot hasn’t worked we’ll with the current radio setup. Don’t assume the new Garmin retrofit will fix the existing interface, and do tell the shop about it before it quotes the job. If you don’t, your wallet could take a bigger hit at the tail end of the project when the aircraft is already reassembled, but now has to be taken apart again for troubleshooting.

Still, ask the shop if it will test the existing systems before starting the work. It should. One nuisance squawk that’s common at the end of a job is faulty panel lighting. You were certain the instrument lighting worked the last time you flew at night, two years ago. Test the lights, note any problems and tell the shop. Retrofits are a good time to modernize the panel lighting and a detail-oriented shop should make suggestions.

Putting Off ADS-B May Be A Bad Idea

We vividly remember when the FAA mandated Mode C altitude reporting equipment. Working with a shop located on the fringe of the New York TCA (now the New York Class B, of course) we witnessed a lot of airspace busts, with customers coming in waving FAA violation letters and needing proof that a shop remedied the equipage issue.

For at least a year after the mandate, it was a steady mess. There were plenty of altitude encoder installations (some requiring transponder bench mods) that got into the wrong hands, plus some aircraft that hadn’t been upgraded yet, but still sailed through the TCA. So it was after recently waking up in a cold sweat with Mode C flashbacks, we thought it would be a good idea to beef up Aviation Consumer’s field reporting on the installation/shop experience aspect of ADS-B upgrades. You know-spend some quality shop time with the folks on the front lines around the country (and in varying airspace) who actually put this stuff in. Our first stop was in coastal New England to NexAir Avionics, a popular shop on the fringe of the Boston Class B.

As we stuffed our camera lenses into the countless gutted airframes on NexAir’s shop floor, it was obvious that putting off an ADS-B upgrade to the last minute-no matter how basic-will be a bad idea. There will be little sympathy. Brian Wolfe, the shop’s avionics manager, makes it clear that his schedule is booking at least four months out. Other shops we talked with for this report, including the busy Sarasota Avionics, have similar if not longer backlogs. But for now it’s still easy. In our estimation, these kinds of installation waiting lists will be a dream by mid-2019. And like most shops, NexAir and Sarasota, to name two, focus on more than just ADS-B upgrades. Its techs troubleshoot, do pitot static certifications, perform specialized maintenance and of course-the priority-do major avionics retrofits. We wouldn’t expect high-volume shops to bump a $60,000 full-panel job from the schedule in favor of a $5000 ADS-B upgrade. Although, Nexair’s owner, Dave Fetherston, told me he’s committed to working with other shops as demand increases. That type of cooperative networking could be the only chance (slim, perhaps) for getting the fleet equipped in time for the mandate.

Some are predicting that shops will significantly raise labor rates because of the ADS-B crunch. In our view, that’s not exactly price gouging because plenty of shops we’ve talked with say the only way to pump out the jobs is by working weekends and in some cases, multiple shifts.

It’s not all doom and gloom. There are stone simple ADS-B systems that might be installed in less than an hour, as uAvionix boasts of its under-$2000 skyBeacon and tailBeacon bolt-on solutions, which are STC approved now. On the other hand, these are low-flying 978 UAT products. There are plenty of Part 25 (jet) airplanes that still need to be upgraded and shops will be scrambling to work on them, too. Where the typical piston or light twin might be down for three to five days for an ADS-B upgrade, a jet solution could take months to complete.

Last, we would allow some time to work out any technical bugs that might exist in the installation. A reader recently reported that his shop is going on month two troubleshooting a major interface that includes new ADS-B equipment and he’s looking for a different shop to get it right. Who wants to be dealing with that 15 months from now when you need might need functioning ADS-B Out just to fly the aircraft off the field?

Wrap It Up

Shops tell us that most customers have a pretty good idea of what equipment they want before coming in the door, but sometimes it won’t fit, it isn’t compatible or simply blows the budget. Good shops have consultants (preferably pilots) who can help with alternative interfaces. This means offering multiple solutions, including used equipment. Be suspicious of a shop that pushes one brand of equipment. It’s no secret that some manufacturers offer sales incentives based on volume. Also understand that avionics retrofits have a way of snowballing, by nature of their complexity. Find a shop that’s willing to brainstorm and even work with you on the project, as reader Bob Reed described of the recent work done to his Grumman Tiger.

“After three major upgrades in the 18 years of owning this airplane, an aging GPS brought me back to Lancaster Avionics in Pennsylvania for what started as a Garmin GTN650 install, but ultimately included dual G5 EFIS displays, a PS Engineering audio panel and major panel work,” Reed told us. As most do, the major panel work came with FAA regulatory considerations.

“Two months ahead of the installation I sat in the plane with shop manager Todd Adams and while we agreed that a full-panel replacement would serve me best, the complexity of the structural modification was beyond what I wanted to tackle-or could afford,” Reed said.

Reed ended up designing a hybrid panel (essentially a metal overlay) in AutoCad and had it laser cut by a machine shop and then powder coated. Retaining the original structure saved time and a lot of paperwork. Good shops should be experts with metal fabrication and painting, but you should ask to see sample panels.

Every shop we spoke with stressed that preparing the aircraft paperwork has become a major effort. Gone are the days of simply making a logbook entry and revising the weight and balance report. Now projects often require customized flight manual supplements, instructions for continued airworthiness and FAA 337 forms. Since you’ll pay for this effort, ask the shop how much of the proposal accounts for paperwork. If an FAA field approval is required (which is essentially a one-time STC), the shop might not be able to predict what the effort will cost. Pressurized aircraft might require engineering approval, especially for antenna work.

Ask the shop if it has a DER (designated engineering representatives) on staff or will it hire an outside engineer to approve the technical data that chases the modification. This can add thousands of dollars to an installation.

Last, avionics require substantial programming and configuration-sometimes a full shop day’s effort. Since not every interface is programmed the same, ask the shop if it will include wiring diagrams and configuration data that’s specific to the interface. Keep this data with the aircraft in case another shop is faced with troubleshooting it.

In a future Aviation Consumer article we’ll look closely at avionics training, including the specific courses offered by manufacturers.