Perhaps to no one’s particular surprise, in early September, Mooney announced that it’s under new management, the Chinese owners having abandoned the premises in Kerrville, Texas. The ownership status remains murky but at this juncture, having reported on a half-dozen resurrections, maybe the question to ask isn’t if Mooney can survive, but can anything succeed in killing it?

By our count, this marks the 12th time the company has either emerged from bankruptcy or been sold to a new suitor determined to revive it in the Kerrville era. The current situation has a management group headed by entertainment attorney Jonny Pollack who tells us he’s busy getting parts and services reorganized and looking for capital to possibly revive production, which essentially halted last year.

CHINESE IN, CHINESE OUT

In 2013, Mooney was among a handful of companies purchased by Chinese interests, in its case by the Meijing Group, a real-estate developer based in Zhengzhou. The purchase price remains unknown but Meijing proved gutsy in investing in their new acquisition. In 2014, it revealed a sleek new composite trainer called the M10T. Powered by a Continental diesel, Mooney was angling for a burgeoning Chinese training market that never burgeoned. In 2017, Mooney saw the logograms on the wall and, following yet another management change, they canceled the M10T after investing what may have been north of $50 million. That same year, the company sold only seven new airplanes.

Dealers and distributors familiar with Mooney’s inner workings say Meijing simply lost interest since the China market wasn’t jelling. Further, the ongoing trade war with China complicated additional direct foreign investment needed to keep the company afloat.

Pollack says he entered the picture as a self-interested customer—he owns an Acclaim—and has assumed oversight of day-to-day operations. He lives in New York state but has been commuting to Kerrville as often as needed.

Is a new investment group being formed to buy Mooney? That’s a good question, Pollack says, and the current ownership plan remains unsettled. Although it has backed away from any daily involvement, Meijing is still at least a minority owner and Pollack says as part of the management agreement, it retains rights to the M10T and to manufacture and market aircraft in China and Africa, if either comes to pass. Beyond that, it’s day by day.

PARTS, WARRANTY

If there’s a bright spot in any of this it’s that the Kerrville plant got a significant makeover on Meijing’s dime. When I last visited there in 2018, the old sheds had been reorganized, the parts manufacturing and tracking system had been upgraded, new production machinery had been installed and significant composite capability had been added. That alone puts Mooney in a good position to achieve its primary goal.

“The primary goal is to service the fleet,“ Pollack says. “There are folks who bought new aircraft and we’re going to honor our warranty on those airplanes. The service centers aren’t really having trouble getting parts,” he adds.

There are believed to be at least 7000 Mooneys in the fleet, a number that represents a substantial parts business. But can the company survive on just that? No, says Pollack, probably not. The factory was designed and built to build new airframes although it has, from time to time, done profitable third-party work. It may do that again, Pollack says. Although it seems improbable now, in the late 1960s and 1970s, Mooney built as many as 700 airplanes a year, double what Cirrus is producing now.

With much of the new production equipment already in place, Pollack says the management group needs to find additional investment to restart the line and make some key improvements. The company has already gotten approval for Garmin’s G1000 NXi but the bigger items on the list include a gross weight increase and a new gear system that incorporates oleo struts.

Premier Aircraft’s Jeff Owen says that’s more important than might be immediately obvious. The ancient rubber donut design is robust and low-maintenance, but he says too many pilots come to grief with it when landing too fast and porpoising straight into a prop strike, or worse.

The gross weight increase is equally important. With Cirrus aircraft at 3600 pounds, Mooneys are behind at 3380 pounds. The Acclaim Ultra I recently flew had an 857-pound useful load compared to more than 1200 pounds for a Cirrus SR22. Would another couple of hundred pounds make the airplane more marketable? Yes, says Don Maxwell, another longtime Mooney dealer in Longview, Texas.

How about a ballistic parachute? Owen says it’s probably a good idea, but at this stage, Pollack says it doesn’t appear likely. He’s more interested in pursuing Garmin’s autoland technology, which thus far is limited to turboprops with the G3000 suite. Pollack says a clean sheet airplane from Mooney is unlikely, but rather what he calls a “hybrid” design that would incorporate improvements to make the airplanes more competitive. It’s unclear, however, how this would address another complaint about Mooneys: small cabin size. The second door Mooney added with the Ultra models at least makes the cabin easier to get into, but it still meets no definition of spacious.

Veteran dealer Don Maxwell told me one recent buyer said he “bought a Mooney in spite of Mooney.” It’s a telling comment on how poorly Mooney has marketed and managed the buyer experience. Pollack acknowledges this as something the new management will have to correct. “The buying experience was never what it could have been,” Pollack admits, “it missed out on some key elements. Mooney was never very good at staying in touch with its owner community. It left Mooney owners to talk among themselves.” Pollack believes previous owners, including Meijing, simply never went far enough in their commitments to make the airplanes competitive in an evolving market.

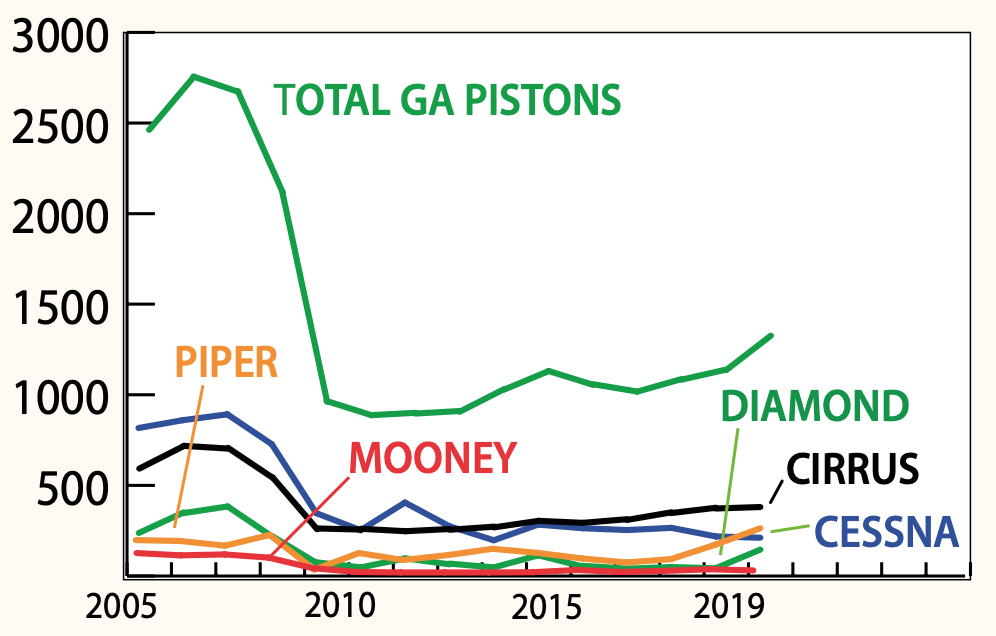

The graph above offers a minimalist snapshot of the piston aircraft market since 2005. (Note that Beechcraft models aren’t plotted to reduce clutter and were subsumed into Cessna’s totals in 2014 when Textron bought Beechcraft.)

The last big peak in production was in 2006, when 2755 piston aircraft were delivered, according to GAMA data. During this period, Mooney enjoyed its highest volume in years, delivering an average of 76 airplanes a year between 2005 and 2009.

Production plunged for everyone in 2009 and hasn’t recovered since. In the past 10 years, Mooney has built 46 aircraft. Cessna—now Textron Aviation—and Cirrus continue to dominate the market, with Diamond and Piper posting smaller numbers. If Mooney contemplates 100 aircraft a year, it will either have to find those unique buyers or steal them from Cirrus and Diamond.

DIFFERENT THIS TIME?

Mooney has circled the drain so many times only to be revived by optimistic new owners as to defy any realistic laws of business. Maxwell—whose relationship with the brand dates to 1969—says he thinks it’s because the airplane is a fundamentally good design. It also has a sizable installed base to form a core parts and support business. Mooney was offering refurb programs for old models and that might still be an expansion option.

As for new airplanes, I have no predictions. Cirrus dominates the market because it’s also a good design, but it has a skilled and aggressive sales force and post-sale customer care that owners rave about. To remain a player, Mooney may have to at least match that.