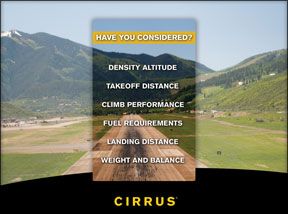

Ever the innovator, Alan Klapmeiers latest brainstorm is to equip the multi-function displays in the Cirrus aircraft with a series of judgment-oriented checklist pages that more or less hector the pilot into pausing just for a moment before committing aviation. Such a thing might, for example, raise a sliver of doubt for the pilot about to depart off a 1500-foot ice-coated runway with a 37-knot crosswind into moderate freezing rain. (Or maybe not.)

Although I think this is basically a good idea, it resurrects unpleasant memories of Sister Salishas fourth-grade class, where it was made abundantly clear that Blocks 3 and 4 of the catechism workbook would be completed before lunch, or we could all damn we’ll starve to death. As we strive ever forward toward systems-based safety solutions, I wonder if there might someday be a red button in the cockpit labeled, “But I Want to Crash.”

It will be invented by the inhabitants of the Village of the Doomed, those poor lost souls who labor frustratingly in the pursuit of teaching the unteachable: good judgment in aviation. Before firing off an e-mail spanking me for such a baldly cynical view, I suggest you read the trouble stirred up by my colleague, John Deakin, over in our sister publication, www.avweb.com. (Log onto the site, click on Columns and then Pelicans Perch #82: The Dreaded Three-Engine 747.)

Deakins column revisits the stink raised by that British Airways crew that crumped an engine on takeoff from Los Angeles in a 747 enroute to London. After analyzing the situation, they decided to carry on to the destination rather than dump a few hundred thousand dollars worth of fuel and return to LAX or land short somewhere else. On its face, this seems like an insanely stupid thing to do. What? Intentionally fly an airplane with a dead engine across the Atlantic? Are you nuts?

Unfortunately, the FAA and much of the daily and aviation press didnt succeed in penetrating the thin crust of incredulity surrounding this incident. As a result, the crew has been all but roasted alive. Deakin, who logged umpteen hours as a 747 skipper, took the opposite view, supporting it with what seems to me to be calm, analytical logic which makes perfect sense. I wont rehash the details here. The column is worth the effort to read.

In any case, he unleashed a river of e-mail, some of which pixeled across my screen. The majority of it came from the are-you-nuts camp, authored by pilots who simply couldnt or wouldnt get past the notion that flying a four-engine airliner with one shut down is simply unsafe because God, or at least Bill Allen, didnt intend it to be flown that way. It is therefore unsafe. Period.

What this says about the overwhelming challenge of teaching judgment is that the effort is occasionally stymied by unalloyed emotionalism that wont yield to logic. Its the classic apple-pie argument. If you argue against what appears to be the safest possible solution to an aviation decision, youre a wild-eyed maniac. Emotional arguments inevitably dredge up the putting-economics-before-safety trump card, as the 747 incident certainly did. Yet the harsh reality is that we do that every day if we didnt, no airplane could get off the ground because it would be too encumbered with safety systems, triple-redundant backups and fat manuals to posit a response for every conceivable situation.

In the end, judgment really is about winging it having the knowledge to think through and analyze a problem to arrive at not just the safest possible solution, but the safest practical solution that still gets the airplane off the ground. Compromise isn’t a dirty word, its a necessity. Without it, a checklist is just words on paper or an MFD.