If Continental Motors ever had any doubts about the aerodiesel market, it erased them in July with the stroke of a pen with the company’s acquisition of the bankrupt assets of Thielert aircraft Engines GmbH. Despite a rocky ending for Thielert culminating in the jailing of its founder, Thielert (and Diamond) put aircraft diesels on the map during the last decade. With its own in-house Jet A TD300 and the addition of Thielert, Continental instantly becomes the market volume leader in aircraft diesel.

The Thielert buy gives Continental four diesel products—the 135-HP and 155-HP Centurions, the 230-HP TD300 and the certified but not-yet-produced 350-HP eight-cylinder Thielert-developed Centurion. Continental and its Chinese parent, AVIC International, also inherit an installed base of some 1800 engines from a company that has manufactured about 3500 engines in total.

When we visited Continental’s factory in Mobile, Alabama, we were told that it intends to integrate the Thielert assets under a common Continental umbrella with unified sales and customer service. The Thielert name will be dropped and the engines will be marketed under the model name Centurion. The main manufacturing plant will remain where it is now, in Lichtenstein, Germany, with service centers to be added all over the world, including the U.S. and China. In Germany, the operating unit will be called Technify GmbH.

In parallel, by mid-summer 2013, Continental was rounding out development on the TD300 and tooling the factory to produce it, although there are no promises on delivery dates. The intro TD300 will get another development round to increase the TD300’s critical altitude with an improved turbocharger.

Global View Continental CEO Rhett Ross is characteristically blunt in describing why the Thielert acquisition made sense: “We have just got to get out from under the U.S. market as the driver for us,” Ross said, chiefly because with no unleaded 100-octane replacement in sight, U.S. market growth is flat and global growth is likely to be nonexistent in gasoline engines. When it announced its own diesel project in 2010 relying on base technology acquired from the France-based SMA, Continental said it wanted multiple solutions to accommodate both a global and a U.S. market that steadfastly refuses to decide on fuel preferences in a world market that already has: Jet A and mogas.

Continental now has more engines to match more fuel choices than any other manufacturer and across more horsepower ranges, even if some of those choices aren’t yet developmentally mature.

In Thielert, Continental is getting a proven engine line, albeit one with minor warts in need of treatment, a healthy installed base, but customer service that some owners have called mediocre at best, although it has improved in recent years.

Thielert’s relationship with its initial benefactor customer, Diamond Aircraft, grew so strained that Diamond CEO Christian Dries started his own company—Austro—to make diesel engines for Diamond airplanes. In addition to Diamond’s initially hot-selling DA42 twin, Thielert made its mark just as the UAV market was emerging and its engines are still found on drones, including the General Atomics Warrior.

That business financed and sustained a modern, state-of-the-art factory in Lichtenstein, Saxony, with a typically well-trained European workforce. Profitable though it may be, Continental will lose the General Atomics military business because of security issues related to its Chinese parent. “That leaves us with a hole we’ll have to fill. We think the civil market is strong enough to do that,” Ross says.

Off to a good start in 2004, Thielert ran into trouble in 2008 after a spate of maintenance issues with its engines gutted its finances because of an over-promised and ill-planned warranty program. Bankruptcy followed, leading eventually to an indictment of company founder Frank Thielert for allegedly systematically deceiving investors when the company went public. In June 2013, a German judge jailed Thielert as a flight risk during his trial.

Continental and the industry it serves is we’ll aware of how the Thielert affair tarnished both the company and aerodiesels, thus the new company will be scrubbed of any identification with Thielert. Ross believes the Centurion nameplate wasn’t besmirched by the Thielert name, thus it will be retained. The larger issue is that the Thielert has been stewing in bankruptcy since 2008 with developmental energies that are unsurprisingly moribund.

Engine Fixes Many customers caught in the 2007 and 2008 Thielert meltdown felt stranded by both Thielert and Diamond. Thielert eventually solved some of the Centurion’s shortcomings and, to its credit, it never stopped shipping parts, although it raised prices to what some customers considered usurious levels. The bankruptcy halted development toward a higher TBO and ridding the engine of disruptive gearbox inspections every 300 hours. When we interviewed Frank Thielert in 2005, a 2400-hour TBR—time between replacement—was promised by 2006, yet seven years later, it remains at 1500 hours for the 135-HP 2.0 engines and 1200 hours for the 155-HP 2.0s engines.

Continental told us getting the TBR to at least 2000 hours is a critical first step in its post-acquisition plans and that will also include increasing gearbox inspection intervals. Continental told us Thielert has on the shelf an improved gearbox that will immediately allow 600-hour intervals and this was expected to happen shortly after the acquisition. It’s unclear why it was never fielded, but we suspect it relates to the company’s bankruptcy stasis. Increasing TBRs will be a taller hill to scale, but will be central to the competitive position of these engines. Our past surveys of owners suggest that thanks to diesel efficiency, even at the lower TBRs and allowing for repetitive gearbox inspections and high replacement costs, the Centurion 2.0 has eked out operating costs equal to or a little less than near-equivalent gasoline engines. Continental thinks the Centurion line is positioned to improve this, if it can reach higher TBRs and improve the gearbox.

As press time, Continental had not announced engine or TBR prices, but we’re told to expect that data soon.

Homegrown TD300

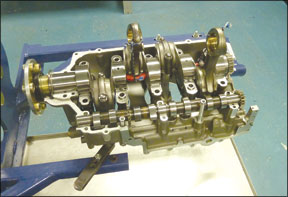

As Continental was closing the Thielert purchase, it was also busy completing work on what will be the mid-power option in its diesel line—the 230-HP TD300. In 2009, Continental purchased from SMA the rights to use the SMA SR305 as a technology base for its own version. Last December, Continental certified the TD300, which addresses the original engine’s shortcomings, specifically its unnerving tendency to quit when reduced to flight idle—especially in cold weather—and turbocharger limitations that hobble its altitude performance. Actually, as of July, the turbocharger improvements were still in the works, but these are expected to appear when the engine reaches the final production version. Continental declined to mark a calendar date for that, however.As aerodiesels go, the SMA engine qualifies as a genuine graybeard, having first appeared in the U.S. in 1998. It’s a four-cycle, four-cylinder engine cooled by air and oil with Bosch-type inline pump injection and minimal electronic intervention. (A limited authority controller provides throttle-by-wire control of the fuel rack.) Although SMA flogged the SR305 at shows for years, it never did much to promote its engine other than limited STCs for Cessna 182 conversions. Only last summer did SMA finally land an OEM for the engine, Cessna, which is using an improved version called the SR305-230E in its new JTA Cessna 182.

Given the inherent operational simplicity of diesels, it’s no surprise that Continental came up with similar improvements to its version of the SMA base. Specifically, the engine couldn’t maintain enough combustion heat to remain alight at low power settings and thus had a limitation requiring high throttle settings on approach. That translated into higher approach speeds than are ideal for a Cessna 182.

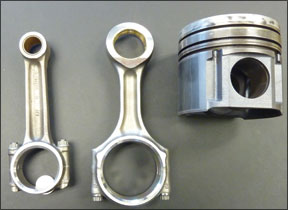

Continental addressed this with a series of tweaks, according to James Ray, the company’s lead engineer on the project. New pistons increase the compression ratio to 17 to 1 from 15 to 1 and a new intake manifold improves the engine’s breathing. Mechanically, Continental retained the SMA base, but added improved through-case bolts, critical structural components in both versions of the engine. Ray said Continental’s tests indicated the original bolts were suffering from plastic deformation, so it increased the material yield strength and diameter.

One shortcoming remains on Continental’s plate: an improved turbocharger. Although it’s a good, economical performer at low altitude, SMA originally spec’d a turbo that lacked sufficient pressure ratio, so the engine’s critical altitude was essentially sea level and its service ceiling was limited to 12,500 feet—anemic for a turbocharged engine.

In the SR305-230E for Cessna, SMA addressed this with a new turbocharger and Continental plans to do the same, although they’re not there yet. For certification expediency, the version of the TD300 we examined in a Cessna 182 at Mobile in July is designated the B model. But the market introduction version will be the TD300C. It will have an improved turbocharger, a critical altitude of 10,000 feet and a service ceiling of 20,000 feet. In our view, that makes it a considerably more competitive engine.

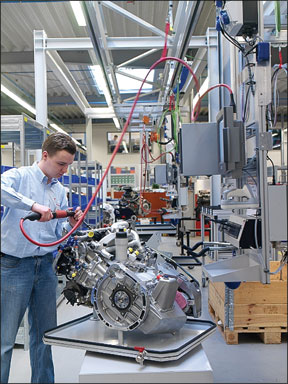

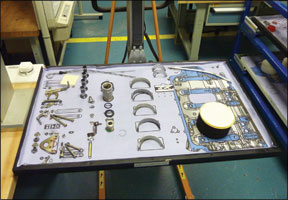

Continental considers the TD300 mature enough to commit to production and when we visited Mobile, it was doing just that. Assembly cells were being designed and tested in anticipation of a type production certificate. (See sidebar at left for more.)

Continental’s Mike Gifford estimates the TD300 will sell for $85,000 to $95,000, with a TBR price of about 80 percent of that. The company hasn’t yet decided if it will market the TD300 with a TBR, meaning replacement or remanufacture, or a traditional TBO. Either way, initial remanufacture or overhaul will be done by the factory.

Market AIMS

In just three years between 2005 and early 2008, Diamond, using Thielert engines that hadn’t yet revealed their foibles, proved a viable diesel market, selling nearly 500 DA42 diesel twins plus some diesel DA40 Star models, mostly in the European market.

Although the aircraft market was stronger then than now, even Diamond was surprised by the uptake. But it didn’t last. The toxic combination of a world recession and Thielert’s bankruptcy tanked diesel sales, even if a trickle persisted. Undaunted by the Thielert fiasco, Diamond remained bullish enough to launch its own subsidiary, Austro, to build diesel engines for its aircraft.

Continental seems equally bullish on diesel and somewhat wary of the gasoline engine market, at least in the U.S., where a future replacement for 100LL remains perpetually over the horizon. Continental still has a strong market in avgas manufacture and parts and Rhett Ross says it remains committed to sustaining that for both OEMs and end users.

But it also considers itself a global player and for Europe, Asia and Africa, that means diesel. When we asked Continental’s VP for sales, Johnny Doo, for his estimate of diesel market penetration, he said it could be 25 percent by 2018. At current world production rates, that would be about 500 aircraft a year or, if the market expands by a third, as many as 650.

We’re not sure if this is realistic or not, but Diamond, on its own, managed to gain about 4 percent marketshare in a mere four years before the economy skidded at a time when diesel wasn’t accepted at all. With Cessna now in the diesel market, can Cirrus, Piper and others be far behind? Continental says it will maintain a dual focus on OEM and conversion markets, channeling through third-party STC houses. The U.S. market for diesel—OEM or conversion—remains uncertain and will be driven by fuel costs and worries about availability. In Europe, Asia and Africa, availability is increasingly the only driver: avgas just isn’t to be found and regardless of what happens in the U.S., 100-octane’s future in the emerging markets is bleak.

“Emerging market,” by the way, has evolved into a euphemism for one place: China. “The way I see it,” says Continental’s Doo, “the one place that doesn’t have many airplanes today is China. That market may not be tomorrow, but it may not be far away.”

It looks like Continental is counting on that and it thinks it now has four engines to fill any conceivable market demand.