Composite materials are not news in general aviation applications. Their traditional advantages-less weight, often-greater strength and relative ease in forming complex shapes-are well-known. Those characteristics, coupled with reduced need for skilled labor to, say, build a wing or fuselage when compared to traditional manufacturing methods make them ideal for aviation applications. And, thanks to Cirrus, Diamond and Lancair/Columbia, along with hordes of experimental designers and LSA manufacturers, its the exception these days for a new aircraft design to be constructed entirely from metal. While its not likely we’ll see a non-metallic propeller hub anytime soon, composite prop blades are readily available right now for many engine/airframe combinations and have been for a few years. Both Hartzell and MT Propellers offer composite blades for constant-speed models-MT also offers fixed- and controllable-pitch props-and Sensenich markets a line of ground-adjustable non-metal props for LSAs and experimentals. But, weve been using metal and wood to build props for years: Why go with a composite prop? What benefits do composites offer when made into a propeller and how do the offerings from these three companies differ? How do they compare to wood or metal props, and can you save any money over the long haul by going composite?

Why Composites?

The same characteristics giving composites an advantage in airframes meant it was only a matter of time before they started cropping up in other major components, like propellers. One solid reason to go with composite prop blades instead of metal is weight: Germany-based MT Propeller says its composite props are significantly lighter than their all-metal counterparts. How much lighter? One STCd MT propeller option for the Cessna 206/207/210 weighs approximately 27 pounds less than a comparable prop from McCauley. Both examples are three-blade models.

Meanwhile, Hartzell also has some good weight-comparison numbers, pointing out a choice of two different props for the Diamond DA40. One is a 74-inch, aluminum-blade prop weighing 62.8 pounds. The companys other choice is a 76-inch composite-blade propeller weighing only 46.8 pounds, despite its slightly larger diameter, compared to the aluminum-blade version. Both are two-blade props.

Performance is another reason to go composite, according to both MT and Hartzell. In addition to the weight savings and how it will impact your airplanes useful load, reduced weight for the engine to spin can translate into less of the available power being wasted by turning the prop. More power is available to put into thrust. Reduced vibration also should result from changing an all-metal prop to composite, since composite materials tend to dampen various harmonics the engine produces, according to MT, rather than support and amplify them as all-metal props can. Not only is reduced vibration good for the prop itself, anything working to dampen

that energy before its transmitted to the engine and airframe can be beneficial. Many owners report smoother operation after exchanging a metal prop for composite.

A final reason is longevity. Metal prop blades can corrode, losing their mass and shape-along with performance. Taxi over some loose gravel and theyll pick up nicks, possibly forming stress risers which must be repaired to prevent loss of a blade tip and a really bad day for the pilot and any passengers. By contrast, MT Propellers says its composite blades have an unlimited life, and can be restored to exact factory-new dimensions.

Sensenich wouldnt go so far as to say their blades have an unlimited life expectancy, but noted composites do not suffer from fatigue the same way metal does. As an engineer at Sensenich put it, “It takes longer for a crack to form in composite materials, and much longer for it to propagate.” Hartzell, however, agrees with MT: Their blades can have an unlimited lifespan. Meanwhile, all three companies pointed out to us that, irrespective of whether composite blades have an unlimited life, their potential life-cycle costs can be much lower than with their traditional metal counterparts.

Comparisons

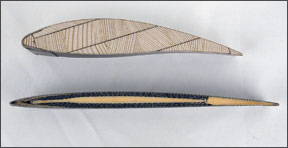

Just like airframes, not all composite props are made the same way. For example, Sensenichs composite blades use a pre-impregnated material consisting of glass fabric and unidirectional carbon fiber. Layers of this material are computer-cut to size and shape, then theyre laid up and heat/pressure is applied for curing. The resulting blade actually is hollow in places, but the layers are cut and laid to create an internal structure.

Sensenichs line of composite props got its start in the demanding airboat market, and only recently has been manufactured for LSA and experimental aircraft. And the blades are all-composite: Unlike the constant-speed offerings from Hartzell and MT, a ground-adjustable prop doesnt need a metal shank, according to Sensenich. Erosion protection is via a nickel or stainless steel leading edge, depending on model.

Another way to think of MT Propellers products is as a wooden blade mounted in a metal base and covered with composite material for protection and durability. The companys composite blades start life as a wooden blank, made from layers of both beech and spruce; the latter is used predominantly in the blade root. Once the woodworking is complete, the wooden core is reinforced by layers of epoxy fiberglass, Kevlar or carbon fiber and sealed by several

coatings of acrylic-polyurethane paint, according to the companys Web site.

To mount a constant-speed blade in a hub, an aluminum ferrule is used, attached to the wooden core with special lag screws. A stainless steel sheath is then bonded to the blades leading edge for erosion protection (de-ice boots, whether electric or alcohol, also can be bonded to the blade for optional ice protection). According to MT, theirs are the only props certified for diesel aircraft engines. Of course, MT also markets composite controllable- and fixed-pitch props.

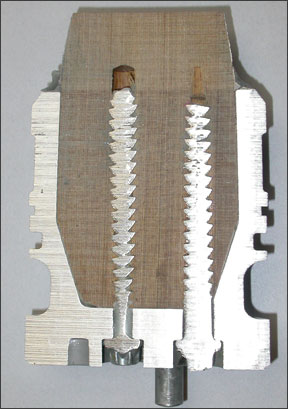

At Hartzell, the companys new-generation composite blades-dubbed “ASC-II,” for advanced structural composites, second generation-are manufactured more like Sensenichs than MTs. For example, instead of a wooden core, Hartzell uses a dense foam, to which are applied layers of material made from carbon fiber and Kevlar, laminating them to the desired thickness and strength. The blade is finished with a layer of E-glass, a common fiberglass type, while a nickel erosion shield and stainless-steel hub-mounting shank are co-molded.

Choices

Once youve made the decision to go composite, choosing the best prop for your airplane depends on the airplane. If youre flying an LSA or experimental in the 100-HP class, youre probably already familiar with Sensenichs conventional fixed-pitch props, and perhaps with MTs fixed-pitch composite products, also. Although Sensenich doesnt offer a composite fixed-pitch solution for certified aircraft as yet, its ground-adjustable line might be the right solution for your experimental or LSA.

If your airplane is FAA-certified and requires a fixed-pitch prop, the only composite choice of which were aware is something from MT Propellers. But thats not a bad thing: Their products have racked up an enviable track record overseas and here in North America, especially when mounted on fixed-pitch Diamond DA20s and LSAs.

For larger airplanes and those with constant-speed props-

whether certified or experimental-the decision gets a bit thornier. For example, if you need an STC, it may or may not be available directly from Hartzell or MT. If not, you’ll need to find a third party with approvals for your airplane. Even then, the STC may not cover the prop you want, or the total cost for the paperwork and prop may be more than you want to pay. If you already have a compatible Hartzell prop and simply want to change out metal blades for composite, it might be more cost-effective to buy the appropriate prop outright.

If youre lucky, itll come down to a choice between Hartzell or MT, and the costs will be similar. In that event, you may want to look at the various specs a bit more closely, as we’ll as talk over things with your prop shop. One question to ask is whether the shop can repair any minor damage itself, or if a nicked composite blade will have to go somewhere else, adding to downtime and expenses. Some shops just arent equipped to repair a composite blade.

Another consideration is the potential weight savings: While saving weight usually is a good thing, some airplanes-the short-body Bonanzas come to mind-often need a little weight out front. Losing 20 or so pounds from the prop assembly might make take away some loading flexibility.

If all things were equal, however, wed probably go with Hartzell for our composite propeller. The companys latest-generation, all-composite blades arent revolutionary, but they do advance the state of the art. And they just look sexy. By comparison, MTs wood-core composite blades certainly do the job, and theyre attractive, also. But the technology going into them just isn’t on par with the latest from Hartzell.

How much will it cost you to upgrade your existing prop to composite? Good question, and one we cant answer without knowing which airplane/engine you fly, whether you want two, three or more blades, and what kind of prop will be removed.

Generally, were talking in the $11,000 to $12,000 ballpark for an outright purchase of a three-blade prop from MT or Hartzell to fit a high-performance single, including the STC. Thats before you trade in your old propeller, if there’s any life left in it.