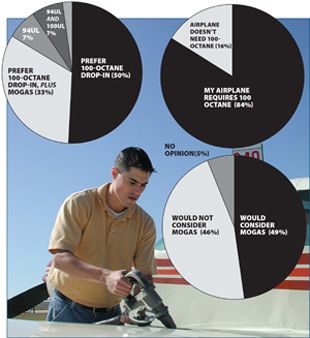

Imagine a world in which youre considering an expensive new luxury car, only to be told by the dealer that fuel to run it may be legislated out of existence in five years, but don’t worry, someone will come up with something. This is exactly the conundrum buyers of new aircraft face and, increasingly, so do owners of legacy airplanes considering upgrades such as paint and avionics. We wondered if lack of confidence in future fuel supplies is putting a drag on the market, so we asked. 310 In a survey published on our sister publication, avweb.com, more than 3100 owners and pilots gave us their opinions on the quest for a replacement for 100LL. Among the findings: One in five owners told us theyre definitely delaying any purchases or upgrades and more than half-53 percent-say theyre either on the fence about purchases or definitely not buying until the fuel situation clarifies. Although the industry alphabet groups and EPA have tried to assure owners that the agency has no definite time schedule for cracking down on the lead emissions that may eliminate 100LL, owners don’t seem to buy this. Only one in five told us these statements made them more confident a suitable fuel will appear soon, but nearly half (47 percent) told us such statements made them less confident. Reader comments revealed a mistrust of EPA intentions. “For the EPA, doing something unnecessary, and potentially disastrous for the most active part of the piston fleet, is clearly not better than doing nothing at all,” said Bill Emde. “Do away with the EPA, not 100LL,” offered another reader. As for a replacement fuel, the strongest preference seems to be for a 100-octane drop-in replacement, with the second-pick preference 100 octane with mogas as an on-field option. There’s little support (7 percent) for 94UL, an approved aviation fuel, a variant of which is sold in Europe. “If something like 94UL becomes the standard, than operators that require higher-octane fuel will be left out in the cold. If were talking engine modifications, I hope somebody is going to study how many high-octane engines even have STCs for burning lower-octane fuel. The cost of developing an STC from scratch could make this option unavailable,” said Dave McClurkin. Although there’s no lack of activity on the fuel replacement front, all of it seems to be top down: Two companies that we know of are proposing 100-octane replacement fuels, ASTM International is considering these for approval and the FAA is getting involved with a new rulemaking committee. But as far we know, no one has asked pilots and owners what they want and what theyre willing to buy. So we did.

avgas burners

Our survey consisted of 32 questions related to replacement fuels and also provided an open comment section. Generally, we wanted to know how closely owners are following the fuel quest (for the survey respondents, very closely), what kind of fuel they want for their aircraft and whether theyd be willing to pay for engine modifications to burn fuels of less than 100 octane.

By early March 2011, 3117 respondents, 98 percent from the U.S. and Canada and 86 percent of them owners or partners had replied. The survey response was lopsided in one regard: 84 percent of those who replied said their aircraft required 100-octane fuel, while the rule of thumb in the industry is that about 30 percent of

the fleet requires 100 octane. The reason for this lopsidedness is obvious: Owners of higher-performance aircraft have expensive investments and they have the most to lose in terms of decreased value which may worsen as the fuel search drags on. Although our survey revealed no strong trend among these owners to sell their airplanes now, a few told us thats exactly what they plan to do.

“If avgas continues to rise in price, I will sell my airplane and stop flying,” said reader David Stevens.

Pilots who replied to the survey don’t have a high degree of confidence that a fuel solution will be found soon enough to stanch market erosion. Almost half-47 percent-told us that last summers announcement by the EPA that there is no timeline for lead regulation makes them less confident in a future fuel replacement. Only 20 percent said those statements made them more confident.

“The FAA does not pay for my fuel or any repairs or anything associated with the planes I fly. The industry has the best knowledge of what planes, pilots and the best gas for the engines they build. The FAA and EPA have long been full of stuff. They need to listen to experts and the industry, not a bunch of armchair want-to-be pilots,” opined Richard Young.

In our view, the larger worry is the owners we hear from who say theyre waiting on the fuel situation to clarify before upgrading their airplanes or buying something new. Based on our e-mail, we would have guessed this to be about one in five owners, but the real percentage may be higher.

no worries

Exactly a third of our survey respondents said they werent worried about fuel and would buy or upgrade accordingly, but 22 percent said they definitely would not do this, while another 31 percent described themselves as on the fence. Summary: More than half of potential buyers feel enough worry about fuel supplies to have it impact their potential purchases.

“I was starting to research engine overhaul versus trade-up options just as the avfuel issue surfaced. I will not spend any capital on a major overhaul, upgrades or trade-up options until the fuel situation has been resolved. If there were a viable diesel option, I would consider that direction and just leave the 100-octane problems behind,” said D. Brown.

Attempts to tamp this down by a don’t-worry-were-working-on-it campaign by AOPA, EAA, GAMA and even the FAA may or may not be helping. The majority of pilots-60 percent-told us they thought the industry shouldnt panic over future fuel development, but 27 percent say they want a more aggressive response to the problem than theyre seeing.

And who should be leading this? Owners are split on this question. About 36

percent thought the FAA should be more involved in fuel development, while 37 percent thought the solution should come from industry. The rest had no opinion.

“I don’t trust the FAA to make the best decisions for the GA community on avgas. Too much influence from lobbyists and not enough input from the pilots and mechanics. Ideally, make a new source for 100 octane from biomass or similar and obtain enough mogas for the aircraft that don’t need the 100 octane, but at a reduced cost. We used to have 80- and 100-octane pumps everywhere; why cant that continue? Were too short-sighted on possibilities and innovation,” said one owner.

Whats Wanted?

As expected, owners of airplanes that require 100-octane fuel want a 100-octane replacement. Exactly 50 percent picked a 100-octane direct drop-in replacement as their first pick, even if it costs more. Why isn’t this number higher, given that eight of 10 respondents own airplanes that require 100-octane fuel? The reason is that there’s strong support for mogas as a second fuel, even among owners of high-performance airplanes. Some 33 percent picked 100-octane and mogas as a second fuel as their preferred replacement strategy, something we see as significant.

But the data revealed some interesting trends. First of all, only about 100 airports have mogas available-only 7 percent of survey responders said their airports had it. But even though the majority of owners said they would consider using mogas, only 15 percent said they had asked their airports to provide it. This confirms what weve heard in our interviews with FBOs: Theyre not hearing owner demand for mogas.

Even though they like the choice of mogas, owners are savvy about the low likelihood of it being practical because of ethanol penetration into the mogas market. Nearly half of them (47 percent) said mogas as part of the GA fuel solution is so unlikely as to be a non-starter, while just one in five consider it very likely. But most do favor an effort to encourage the FAA to pressure EPA to segregate at least some of the domestic U.S. premium mogas supply from ethanol, sparing it for aviation use. The likelihood of this happening seems low, but owners favor it anyway.

94UL, Mods: No, thanks

Our survey revealed little interest in 94UL as a replacement avgas. There’s also not much enthusiasm among owners for modifications that might be necessary in order to burn a fuel of less than 100 octane.

Just 7 percent favored 94UL as a drop-in replacement for the current leaded avgas, compared to 50 percent who want a 100-octane solution of some kind.

When we asked owners what kind of modifications they would perform in order to burn a lower-octane fuel, more than half said they would be unlikely to consider any modifications. Only 8 percent said they would be likely to make mods, while another 24 percent said they would be somewhat likely.

What kind of mods? We asked about installing low-compression pistons, full FADEC systems, operating at reduced power or perhaps buying a simpler electronic ignition system to improve detonation margin. Owners seem to like that last idea best. Almost 40 percent said they would consider a system like that, if its technically feasible. (Were not sure it is.) Operations at reduced power and low-compression pistons are a loser. Neither of these generated more than 10 percent approval. A full-up FADEC appealed to about 14 percent of those who replied-not bad, but not evidence of a strong market, in our view.

Comments from Steve Cochard summed this up: “I have a Piper Arrow IV. Just replaced the engine with a Lycoming factory reman. It is an IO-360 and is high compression and therefore requires 100LL. Cost a ton of money to repower the airplane, and the performance is now awesome. I don’t want to pay additional money to decrease the power or make modifications to the engine to unpower the airplane. Doing that in this case would, one would think, be stupid.”