If new aircraft manufacturing ventures require a degree of faith to succeed, Austro Engine GmbH, grafted on to the side of the Diamond Aircraft factory in Wiener Neustadt, Austria must be the industrial equivalent of the Vatican. It’s not that Austro has no chance of success—the reverse may very we’ll be true—but that it’s investing heavily for a future that many in the industry can’t yet draw into sharp focus.

The uncertain future of avgas—it seems to be all but dead in Europe and approaching life support in the U.S.—should make diesel engines a natural for strong growth. But with aircraft sales in the tank, that growth has failed to materialize. Gasoline powerplants still outsell diesels by a wide margin and some diesel projects—DeltaHawk, for instance, and Thielert’s slow-as-50-weight-oil life extension efforts, have a forever-over-the-horizon quality. The exception is Austro.

This is a company that sprang practically fully formed onto the engine scene in 2008 after Diamond CEO Christian Dries got fed up with customer support and development efforts of Thielert AG, whose Centurion engines Diamond had selected to power its innovative DA42 twin. Given what appeared to be the difficult technical problems Thielert encountered in converting a Daimler-Benz auto diesel for aircraft use, there was no reason to believe Austro would have it any easier.

And it may not have, but during our recent visit to Austro’s factory in Wiener Neustadt, we learned that Austro has been the rabbit to Thielert’s turtle. In the short space of 30 months, it has invested heavily, improved the engines and recently gained approval for a 1200-hour TBO, up from the 1000 hours it started with.

By the end of this year or early next, it hopes to authorize 1500 hours and eventually 2000 hours. The need for speed is obvious. For as attractive as aerodiesels are, they don’t really begin to turn the economic corner until they achieve what diesels are traditionally good at: long service intervals between overhauls.

The Big Idea

Austro came out of the ground in 2007 with quite a start as a result of Diamond Aircraft’s frustration with the Thielert 1.7 diesels it originally selected for the DA42 twin. After initial strong sales and good performance, especially in fuel economy, problems surfaced. The Thielerts had a hobbled initial TBO (1000 hours) and required periodic inspection and/or replacement of such critical items as gearboxes, clutches, fuel pumps and alternators.

Although owners grudgingly accepted the maintenance load, both Diamond and owners were unhappy when Thielert’s support structure proved incapable of quick turnarounds for parts and the engines themselves began to experience faults and failures. In the December 2007 issue of The Aviation Consumer, we reported, “Thielert is uniformly criticized for slow support, inefficient warranty and a nonexistent parts chain.” At the time, many owners complained that they felt the Thielerts would never be high-TBO engines. (They still aren’t.)

In the meantime, Diamond CEO Christian Dries was already working on Plan B, which turned out to be a crash program to develop a new diesel engine to replace the Thielerts. Austro was founded in 2007 in a new building located directly adjacent to Diamond’s expanding factory in Wiener Neustadt, south of Vienna. Although the new Austro diesels were to be the primary product, the business, to a degree, was built around the kernel of an existing engine, a small 50-HP rotary now called the AE 50R. Its primary market is for light motorgliders, where it’s typically mounted on a stowable mast.

When it turned to the diesel market, Diamond followed Thielert’s concept of a “aeroizing” an automotive diesel engine, the Daimler-Benz OM640 that’s used in the Mercedes A-class. This vehicle—a kind of a mini-van crossover with luxury features—is seen all over Europe but hasn’t been introduced to the U.S. yet. It has been manufactured in the millions, in both gasoline and diesel variants.

That high volume is what attracted both Thielert and Austro to the OM640, for along with high volume comes the kind of high-level statistical process-based quality control that’s difficult to achieve in the aviation industry.

Further, Austro retained the OM640’s core just as it comes from the factory, including the heavy cast-iron crankcase and head that are common to diesels. Thielert, on the other hand, in an effort to make its engines more aircraft friendly, retooled the block and head in aluminum. During our tour of Austro, Christian Dries pointedly gestured toward the Austro’s head and said, “You can’t do better than this.”

Off with the New

When we arrived at Austro’s plant on a rainy Austrian morning, we were surprised to find no long assembly lines or the clatter of air tools. It sounded more like a field overhaul shop which, in a way, it somewhat resembles. What we did find were about two dozen fresh-from-the-factory OM640s reposing on pallets—about 20 minutes worth of production for the factory that makes the engines.

The motors were fully dressed and ready for dropping into an A-class chassis. When we asked Austro’s director of sales and marketing, Peter Lietz, why Austro couldn’t just buy the cores, he said that wasn’t an option. By agreement with Daimler, the engines are diverted from the standard automotive assembly line and shipped off to Austro whole. Given how the automotive supply chain works and the fact that quality is based on high volume, this makes sense.

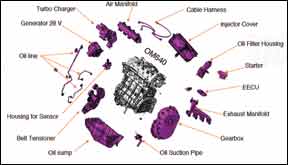

Nonetheless, what we saw next was no less startling. From the core OM640, off comes the turbocharger, the fuel injection system, the airbox, the sump, the alternator and a host of smaller parts—all factory-fresh, never-used parts that are sent off to the crusher, according to Austro. It then does its own Cinderella conversion of the core into a certified aircraft engine.

For the critical aircraft components, Austro didn’t go it alone but relied on MBtech Powertrain GmbH for the core engine, Hor Technologie GmbH for the gearbox and Bosch General Aviation Technology for the engine control units and fuel injection system.

Two of the most critical components are the gearbox and a dynamic torsional damper, which Austro says is a lifetime part rather than the more traditional clutch used in the Thielert engines. Similarly, the Austro gearbox is a to-TBO part, while the Thielert engines still require gearbox removal and inspection at 600 hours on the way to a 1200-hour TBO.

The conversion is done on a one-by-one basis, starting with stripping and finishing with the build-up of completed engines on the bench, then a trip to the test cell for initial run-in.

Low Volume

Although production is ramping up slowly, Austro’s Peter Lietz told us the company has, in 2½ years of production, fielded about 440 AE300s, with a total fleet time of about 120,000 hours. During our coverage of Aero in Friedrichshafen, Austro announced that it had just received EASA approval for a 1200-hour TBO and it hopes to go to 1500 hours by the end of 2012 or early 2013.

When the AE300 was initially certified, it had a 1000-hour TBO and some parts required periodic replacement or inspection. At 300 hours, the initial engines required an alternator change, a high-pressure fuel pump change and a torque check of the flywheel.

Lietz told us that these items were marked for replacement so Austro could build a statistical matrix for life extension. “There was an exchange program on these parts so customers could send them back and Austro could inspect them for wear,” Lietz said. Intervals on these parts have now been increased to 600 hours. Although the gearbox must be removed for the flywheel inspection, the gearbox remains a lifetime component.

Another thing Austro has done is to tease a little more power out of the AE300s. At Aero, Diamond took the wraps off a new model, the expanded-cabin DA52, which the company says can seat five people, or seven in a pinch. This airplane is powered by 180-HP versions of the AE300, which led us to ask about how much power these engines are capable of producing with further development. Lietz thinks they’re about at the limit with a four-cylinder, turbocharged diesel. The additional power comes from a boost in manifold pressure—up to 39 PSI from about 30 PSI—and some additional fueling. “That’s the big advantage of an electronic engine. You can control the amount of fuel you use compared to the amount of boost pressure you have,” Lietz explained. The piper to be paid, however, is durability.

“You can pull more power out of these engines, but then you reduce the reliability and the safety margins,” he adds. The additional power generation has a small impact on peak cylinder pressures, but the power push can go only so far. “We are still in the safety margin of Daimler. We make all of these changes with Daimler because these guys know exactly what we can do with the engines,” Lietz says.

With so few fleet hours and the first engines just now coming back to Austro for overhaul, we wondered if either Daimler or Austro has statistical modeling based on what they’ve seen so far. The answer is yes. Both companies have computer durability modeling predicting engine life cycles, but they need more field data to tell if the models are accurate.

When we visited Austro in March of 2012, the first 1000-hour engines were just coming back for overhaul. These were operated by Ethiopian Airlines as trainers and flown several hours a day every day, according to Lietz. The engines were completely disassembled and all the components were wear checked. “From the outside, they looked dirty. But there were no signs of coolant or oil leaks,” Lietz told us.

And what about wear? “Nothing really,” Lietz said. The engines would be reassembled with new gaskets and seals and eventually placed back in service. However, for its initial AE300 customers, Austro is offering an exchange engine program. “Right now, those customers are getting new engines because Austro doesn’t want them to be delayed and the infrastructure isn’t in place for quick field turnarounds,” Lietz said, although it will be eventually.

For now, Austro is offering a flat rate on the overhauls: about $19,400 (14,000 Euros). As the volume picks up, Austro will eventually set up field overhaul facilities and prices will become more competitive. We suspect, however, that the quoted flat rate here will eventually be higher, perhaps more in line with gasoline engines of similar horsepower such as the 180-HP Lycoming IO-360s used in the DA420-L360. On the other hand, if the Austros live up to diesels’ reputation for longevity and routinely make overhaul times beyond 2000 hours, the per- hour engine reserve could be lower than that of gasoline engines.

And by the way, in case you’re wondering what will happen when Daimler phases out the OM-640, as car companies inevitably do, Austro has made long-term supply arrangements. (Presumably, running the engine line for a couple of extra days could produce a lifetime supply of the engines, although it would require a big investment to buy them.)

More Power

With the Daimler-based OM640 reaching its power limit, what’s the next step up? One possibility is what Austro is calling the AE500, which is a variant of the Steyr 275-HP M16 six-cylinder turbodiesel. The engine has some advantages in that it’s a monoblock so it can tolerate higher cylinder pressures and output and rather than a common-rail injection system, but an old-school pump injection design. The AE500’s major drawback, however, is weight.

At 550 pounds (275 kg), it’s heavier than a traditional high-horsepower aircraft gasoline engine, but it currently lacks the power output. (A version of this engine is used in military HUMMVEES and also marine applications.) What’s next for Austro is the AE440, a purpose-made V-8 diesel being developed in conjunction with Eurocopter with help from the European Union’s Clean Sky project. (Diamond and Austro, if you haven’t gathered by now, is big on joint developmental ventures.) In developing the 440, Austro is looking ahead at least a decade and sees in the market a sizeable hole between the highest horsepower gasoline piston engines and the lowest power turbine engines which are light, but fuel hungry.

Because of their exceptional fuel economy, Austro also sees a potential market for its diesels to replace the turbines used in APUs, both ground based and for aircraft.