You’ve decided that it’s time to buy an airplane, or you own one and you want to upgrade it with a glass panel or a larger engine. The “how will I pay for it?” refrain has gone through your head more than once. Now you have to listen to that voice. It’s time to get the money and do the deal. We’ll tell you your options and how things work in the aircraft finance world.

Ways to Pay

You can always pay cash. As we researched this article, we were more than a little surprised to discover that cash purchases were more common than we expected. According to aircraft brokers we spoke with, the combination of depressed prices for airplanes and generally lousy rates of return on savings and investments have caused people to be more willing to use money they would otherwise be investing to buy an airplane.

However, for the majority of us, the real world means you’re going to have to get a loan.

An option used by many buyers of piston singles and twins is a home equity loan. Rates have been running as low as three percent, and the interest is often deductible. Plus, the collateral is your home, not the airplane, so there is no lien on the airplane to deal with when it comes time to sell.

If the home equity route won’t work, it’s time to find a lender who finances airplanes. They exist and the rates charged aren’t bad. As of mid-June 2013, rates for piston singles were starting at five percent—the number varying with the size of the loan, term length, and age and type of airplane. Loans of less than $100,000 or on airplanes older than 20 years are higher. It costs the bank the same to process a loan for $25,000 as it does for $250,000, so the interest rate for the $25,000 loan will be higher.

Aircraft loan terms are usually, not always, for 20 years. Fixed and fixed-for-five-years-then-variable rates are generally offered—the fixed rate being slightly more expensive. We were told by aircraft finance broker Dan Garzelloni (www.milehighmoney.com) that the average owner holds an airplane for 33 months, so a variable rate loan may be the more economical strategy.

Finding a Bank

The chances are that your local bank won’t know how to handle a loan on a general aviation aircraft. If it does, that’s great; otherwise, the next step is local, regional and national banks that do aviation lending. The challenge is finding one that specializes in the type of airplane in which you are interested. According to aircraft broker Tom Kelly (www.shamrockaircraft.com), most banks will not loan less than $100,000 and won’t touch homebuilts; some won’t loan money for singles more than 30 years old or any piston twins.

One way to find a bank that likes the type of airplane you do is through a type club—Cardinal Flyers or the Short Wing Piper Club, for example. If you’re looking at a homebuilt, talk with members of your local EAA chapter.

In our opinion, the better way to find the right airplane financing is to go through an aircraft finance broker—more about them in the sidebar on the next page. It’s analogous to a mortgage broker—the broker works with several banks and finds the best deal for you based on your finances, as we’ll as the airplane you want to buy or upgrade you want to make.

Applying

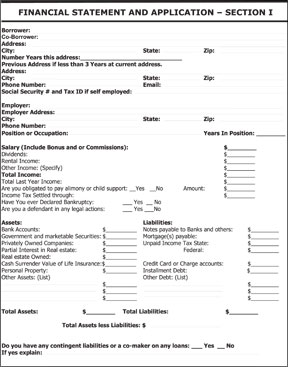

The application process is almost identical, no matter which bank is going to do the lending. You’ll provide your financials—that means tax returns for the last two years and probably something to show how you are doing year to date or your most current pay stub. The bank is looking for you to show your earnings are stable—we were told that many buyers are entrepreneurs whose earnings flow can vary—and that you are liquid. You’ll need to show that after you make a 15 or 20 percent down payment (as much as 25-30 percent if you’re doing a leaseback to an FBO or buying a new airplane that will depreciate quickly), you’ve still got a total of 24-30 months of loan payments in liquid assets, not including your 401(k) or IRA.

According to Dave Madden, marketing director of aircraft finance broker NAFCO (www.airloans.com), banks don’t want to see you dipping into retirement funds to finance a recreational vehicle—and they do want to see that you have the liquid capital on hand to pay for maintenance and fuel. They’ve seen too many customers who think the real cost of owning an airplane is just buying it and then can’t afford to maintain it or make payments—so the bank repos a piece of junk.

You’ll fill out a standard loan application that gives the bank (or the broker) permission to “pull your credit,” or get your credit reports. Figure on a minimum credit score of 700 to qualify for a loan. We were further advised by Dan Garzelloni, proprietor of Mile High Financial (www.milehighmoney.com), that every time your credit is checked, it dings your score two to five points—more if several checks are made in a short time. So if you apply to several banks for a loan and they all pull your credit, your rating will take a hit. That’s one advantage to using a broker—the broker pulls the credit and each bank approached by the broker uses that set of reports, so your credit rating only takes one hit.

Lenders will usually lend only a percentage of the Bluebook or VRef price (or the sale price if it is lower). It can be challenging to get a big loan on a bird whose owner has decked it out so we’ll that it’s worth far more than book price. Plan on making a larger down payment on one of those. You’ll need to provide some form of government-issued photo ID.

Finally, the bank is going to want to know about the collateral—the aircraft you’re buying or upgrading. The age and time on the airframe and engine matter—7500 hours is getting to be high time and it may make getting a loan more difficult or may up the interest rate you’ll pay. For best terms, according to Dave Madden of NAFCO, go after an airplane with a low-time engine. A title search must show a title with no liens or ones that will be removed before or at closing. The airplane should have all of its logs and no damage history—either one reduces the number of potential buyers should there be a repossession.

Approval

We learned that the biggest delay in getting financing approved was not giving a lender everything it wanted up front. Once you provide everything, approval for a loan generally takes one to three business days, even if you are applying with a few others to buy the plane together and put it into a Sub S corporation or LLC. If the airplane is a bit unusual or old, it may take longer. Aircraft broker Tom Kelly told us that if approval goes into what he called “limbo,” that is, it doesn’t get approved in more than a week; his experience is that the aircraft sale isn’t going to go through.

For airplanes under $250,000, most lenders do not need to see the prebuy inspection report, although most will insist on a prebuy. An appraisal is generally not needed for airplanes under $1,000,000.

Early Approval In speaking with bankers, aircraft finance brokers and aircraft brokers, each and every one of them said that the best procedure to follow when you know you’ll have to get a loan to buy an airplane is to get “pre-approved” (yes, we know that’s a physical impossibility, you’re either approved or you’re not). That means you get approved for a loan before you settle on an airplane—you work with the broker or lender you’ve chosen, discuss the general type of airplane and price range, go through the application process and get approved for a loan of up to a given amount of money. The process takes two to three days. The approval is good for 60-90 days.

As aircraft finance broker Wally Zook (www.zookair.com) told us, early approval is a wise move—with approval in hand, you shop for the right airplane, negotiate the price, do the prebuy while keeping your lender in the loop and then close the deal fast.

Closing

Once your loan is approved, closing can happen in two days if everyone cooperates and overnights the paperwork. NAFCO’s Dave Madden walked us through the process:

The lender prepares and the seller signs the FAA Bill of Sale, FAA Form 8050-2. It is a carbon-copy form that must have an original signature, it cannot be signed electronically. The seller sends the signed original to the lender, title company or an escrow agent who holds it in preparation for closing and filing. (If the deal falls through, the Bill of Sale is either shredded or returned to the seller.)

The lender prepares and the buyer signs an application for registration of the airplane, FAA Form 8050-1, and sends it, minus the pink copy, to the lender, title company or escrow agent to hold for the closing and filing. The pink copy is held by the buyer and will serve as the temporary registration to be carried in the airplane until the white copy is received from the FAA following the closing and filing of the documents with the FAA.

The lender prepares and the buyer signs a promissory note for the loan and sends it to the lender.

The lender prepares and the buyer signs a security agreement giving the lender a security interest in the airplane—which allows the lender to repossess the airplane if the buyer doesn’t make the payments. The buyer sends it to the lender, title company or escrow agent, who holds it in preparation for the closing and filing—the security agreement is filed with the FAA to record a lien on the airplane in favor of the lender.

With the paperwork signed and in the possession of the lender, title company or escrow agent, the buyer and seller complete the transaction. The buyer confirms the airplane is satisfactory and gives the seller the remainder of the “money down” on the deal. The buyer emails the lender to confirm that the airplane is satisfactory, that he wants the closing to go forward, and the loan funds can be released. The seller emails the lender to confirm receipt of the “money down” from the buyer and that the closing can go forward.

Upon receipt of the emails, the lender releases the loan money, usually via wire transfer, and advises the buyer and seller. The lender either physically files the Bill of Sale, application for registration and security agreement with the FAA or directs the title company or escrow agent to do so. Some lenders and all title companies and escrow agents have offices in a location in Oklahoma City, where they can immediately give the sale documents to the FAA for filing.

There is usually some fee due to the lender at closing—to cover the title search, FAA filing fees, personnel and brick-and-mortar costs at the lender. We found them to be on the order of $500. The buyer pays that fee with a check held by the lender until the closing occurs. If an escrow service is used—not common for transactions under $100,000, unless the seller is uncomfortable sending a signed Bill of Sale to a lender before closing and wants a third party to hold it—the escrow service fee is usually split between buyer and seller. It is often tied to the value of the transaction, but figure on $500 or more.

That’s it. The airplane is yours (and the bank’s); now all you have to do is make the payments, insure it, fly it, fuel it, maintain it and then start wishing it were a little faster and carried a little more …