Eyeball the typical proposal for a modern avionics installation and you might consider scaling the job back to include used avionics. But sourcing the equipment—especially more advanced gear—is challenging and risky. We’ve seen our share of buyers get stung by what initially seemed like a smoking deal, but in the end they paid as much or more than what it would have cost if they bought new stuff.

But that doesn’t mean you can’t save some money on select equipment, especially if you can live with older technology. For no-frills VFR machines, used gear is worth considering. In this article we’ll look at some common used-market buys, but also focus on installation considerations, which could make used purchases anything but a bargain.

AIRWORTHINESS

That should be a big consideration when searching the used market and it mostly comes down to traceability, service history and paperwork—which potentially add sizable costs to the project. It’s the Wild West out there. Some used avionics are sold with all the supporting regulatory paperwork an installer will need to officially sign off the installation. Others might come with nothing that can support a legal logbook entry. This means you’ll have to pay for bench time to have the equipment evaluated (which could mean tweaks and major repairs) to generate the FAA Form 8130-2. This is the coveted airworthiness documentation that tags along with the equipment being installed. Forget the so-called yellow tag—this once had marketing value because on a shop level, equipment stamped with a yellow tag generally means it’s serviceable—or the difference between a shop tossing it in the trash bin after red-tagging it. (The condemned gear get red-tagged. Ones that are repairable have green tags.)

That’s why we like sourcing used gear from avionics shops that maintain an FAA Repair Station. They’ll have stringent quality standards in place and will know what they can and can’t install, and endorse in the logbooks. If you’re determined to source your own used gear, partner with a trusted shop to backstop your shopping. Busy shops might not want to get involved with used equipment unless they removed or sourced it themselves. They likely bought it right, bench tested and repaired it, have installation kits for it and marked it up for a good profit.

Gear that has recent factory paperwork will come at a real price premium, and shops that don’t have the bench repair capability will have to send it off. This is where it gets tricky, and where you could spend more for used equipment than the same item that’s factory new with a manufacturer’s warranty.

SOURCE ‘EM RIGHT

Consider the warranty before buying used electronics from anyone. Typically, shops selling used equipment tack on a 30-, 60- or 90-day warranty. Except maybe for brother-in-law deals, anything sourced privately is sold as-is. Facebook, owners groups, web forums, FBO bulletin boards and eBay are just some places to hunt for bargains.

On Facebook, the U.S.-based private Aircraft Avionics Exchange group has over 20,000 members and was created to buy and sell equipment. Even if you don’t buy anything, it’s worth joining to keep tabs on used market pricing and which equipment is in demand. It’s a well- run and resourceful page.

There’s also Barnstormers.com and Trade-A-Plane, two popular online sources for used gear. They have search engines for narrowing your hunt, but you might have to ask lots of questions. Does the equipment come with installation kits? Antennas? And ask where the equipment came from. If it’s used it might have been in a crash, which isn’t really a bad thing unless the wreck involved water, fire and, well, bodily impact.

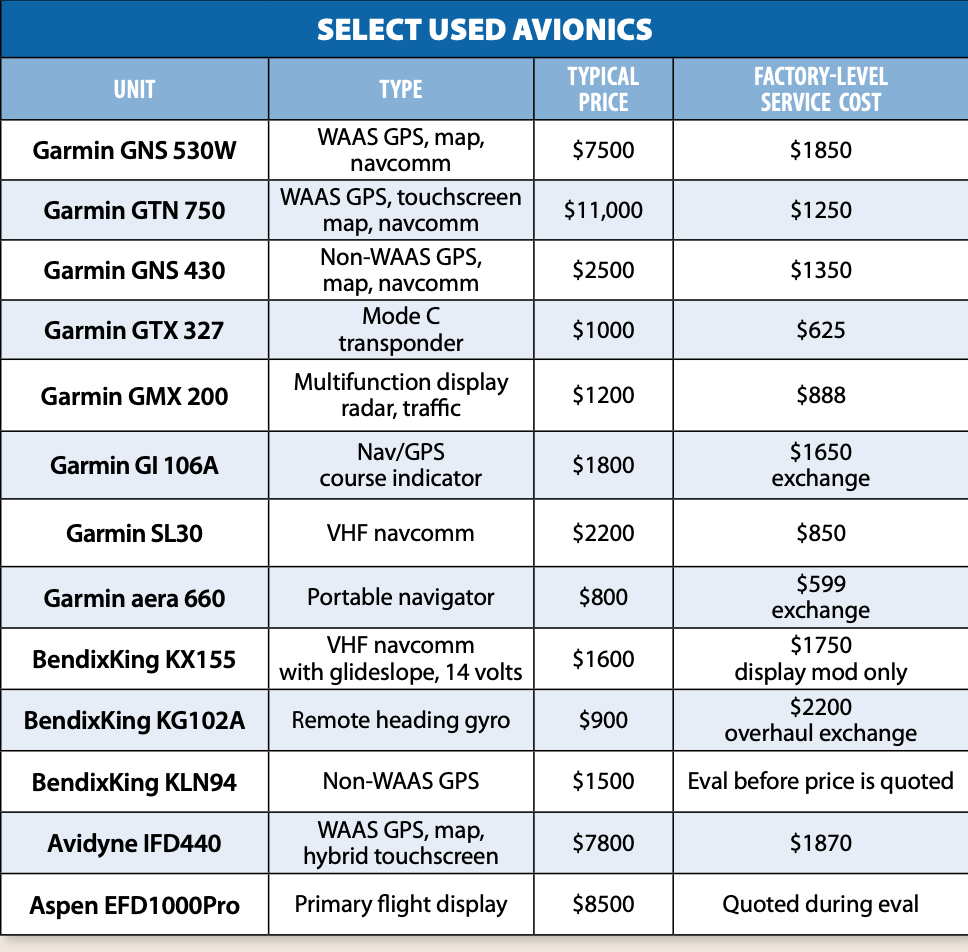

Before sourcing the gear from anyone, keep the chart on page 11 handy. It shows the typical current selling prices of some common equipment and what a trip to the manufacturer will cost for repair or exchange. In many cases the numbers are big. In others, the product isn’t supported at all.

GPS NAVIGATORS, EFIS

Perhaps the most sought-after used systems are GPS navigators, including Garmin’s legacy GNS 530/430. The first 28-volt models are no longer supported—we wouldn’t suggest buying one at any price. The non-WAAS ones that will work at all voltages (14 through 28 volts) might even be questionable because a WAAS upgrade at the factory will cost several thousand dollars, which doesn’t include the $1080 flat-rate repair cost if something else needs to be fixed. When shopping, pay particular attention to cosmetics. This includes the display lens (it’s a common part that needs replacement, especially as owners obsessively clean them) and the bezel buttons. Remember, these boxes have been in service since 1999. Most have lived hard lives.

At press time, Avidyne was running a GNS trade-in promotion for credit against its IFR-series navigators. This “Cash For Clunkers” program gives a seller up to a $1500 credit against an IFD. This means installing shops are taking older Garmin navigators into inventory, but they might be older units no longer supported or needing repair.

Avidyne’s flat-rate repair pricing for its IFD units is $1870 for the standard repair-and-return service, and $2210 for an advanced exchange, which could result in less downtime. But worth mentioning if you source an IFD440 or 550 on the used market (we’re starting to see them surface) Avidyne’s policy is that normal repairs may be subject to an additional hefty fee if the glass and/or bezel is in unserviceable condition. That includes scratches on or anti-reflective coating that’s missing or worn from the display lens. Do a careful inspection before buying a used one.

If you want to trade your vintage Garmin GNS unit in for a current GTN Xi model, Garmin has a trade-in program. It’s offering a $2000 credit for GNS 430W/530W units against a new GTN 650Xi, and $3000 for a GNS 530W against a flagship GTN 760xi. The units must be flightworthy and include the original install rack and backplate.

BendixKing’s KLN90 and 89B series GPS units aren’t easily supported, especially when displays fail. We would avoid them, and even the later KLN94 because it can’t be upgraded to WAAS.

Garmin has discontinued repairs for its early-gen navigators including the GNC 300XL, GPS 155XL and GNC 250XL. There are a lot of these on the market and while they are generally good utilitarian boxes, we wouldn’t buy them for lack of support.

Last, Garmin’s new line of budget navigators is changing the market of used GNS units. Compare a used GNS 530W generally priced around $7500 (for one that has solid paperwork, good cosmetics and recent factory repairs) with a current GNC 355. It has touchscreen, wireless connectivity, a built-in VHF comm radio and a list price of $6995. It doesn’t have VHF nav capability, but you might not need it—a different topic altogether.

Shop carefully for GPS systems with these kinds of comparisons in mind, and don’t forget the required external course indicators that will add thousands to the price. We like that Garmin’s new line of navigators can work with a generous variety of third-party nav heads—including the King KI209. This can save some money if you have one that’s compatible.

Unless pulled from a wreck, there are few EFIS displays on the used market. The interface for most is complex and ripping the installation apart to upgrade doesn’t always make sense. In our research we spotted a couple of Aspen flight displays, so we asked the company about flat-rate repairs.

“We evaluate them and quote the price for repair; we don’t force customers into a flat-rate price,” Aspen’s Michael Studley told us. We like that approach.

One vintage EFIS display we would avoid at any cost is the Sandel SN3308. It never had a robust connector assembly and that means intermittent connections—a problem that makes many owners remove them for good. It’s not worth it.

TRANSPONDERS AND NAVCOMMS

Used VHF navcomms might make sense, and perhaps the most popular navcomm radio of all time is the King KX155/165 series. The used market is saturated with them, but not all will work for all applications because they are voltage specific. Ask before buying if the operating voltage isn’t specified, and many private sellers (and buyers) don’t understand that if you slide a 14-volt radio into a 28-volt electrical system you’ll have a smoke show. The KX165 version has the VOR/Loc converter board required to drive analog HSI systems. The KX155A/165A series are later models that only work on 28 volts.

Display failures are common with these radios and the vendor that used to supply them is gone. That forced BendixKing to create a modification that replaces the gas discharge display with an LCD one. A few years ago the company came up with a $1750 refurbishment program that converts the display and also spiffs up the front bezel, display lenses and knobs. The display conversion kit alone is north of $1300, which also includes a replacement PC board.

We asked BendixKing for a flat-rate repair schedule for this radio (and others in the digital Silver Crown series), but were told it doesn’t publish those prices. Instead, it quotes the flat-rate repair on a case-by-case basis once it evaluates the unit. For that reason, we say be careful buying this equipment unless you’re prepared to spend thousands for a repair. On the other hand, a field repair at a qualified shop might be possible.

And for repairs that an avionics shop can’t handle on its own bench, we favor the Mid-Continent Instrument and Avionics service center (www.mcico.com) in Kansas. It has been working on King equipment for 46 years, and its bench techs have an average experience of 26 years. For fixing the old stuff, experience matters, and shops are finding

it difficult to staff bench talent to troubleshoot and repair analog circuits. Mid-Continent keeps a supply of exchange units on hand, which expedites the turnaround.

Southeast Aerospace (www.seaerospace.com) in Florida is another source for exchanges and repair, plus it has an AOG service. Both companies have a searchable database, which is a good reference for deciphering the long part numbers.

If you want to steer clear of an aged KX155, the better option for a used standalone navcomm is the Garmin SL30. It’s easily supported, it’s a good performer, has a slim chassis that saves space in the radio stack, plus it has a serial data interface for connecting to some EFIS models. These radios fetch good money—we found some selling for around $2500.

ADS-B upgrades have trickled a healthy supply of transponders into the used market, including lots of units we would avoid. These include the Narco AT50, King KT76, Collins TDR950 and ARC RT359. If we favored one Mode C model it’s the Garmin GTX 327. It’s digital, reliable, has smart features and Garmin’s flat-rate repair price is reasonable. A good price for one right and tight may be $1000 or so. Before buying any used transponder, read the budget transponder roundup in the February 2020 Aviation Consumer. There are affordable options that make better sense than spending good money after bad on an old clunker.

WHAT THE PROS SAY

The shops we talked with suggested that bargain-based used equipment is more common for basic, entry-level airplanes rather than go-places traveling machines.

“The right used equipment can work we’ll for the owner who flies a VFR Cherokee or Cessna 150, to name two examples. We see few Bonanza, Mooney and Centurion owners gambling with aging used gear,” said TJ Spitzmiller at Sarasota Avionics in Florida. His shop is seeing a lively market for used Garmin navigators and also King KX155 radios, but he noted that parts are getting difficult to find for vintage equipment. That means a hefty flat-rate factory repair.

If there is a particular model we didn’t mention here that probably means it isn’t worth buying, but if you have one in mind drop us a line and we’ll offer our two cents. We also didn’t cover used instruments and avionics. This is a broad category (filled with all kinds of caveats) that we’re saving for a separate article coming up in a future issue of Aviation Consumer.