Despite pilots’ most intense desires, airplane components wear out. Fortunately for their wallets, the major stuff on general aviation airplanes that are hangared and flown a few hundred hours a year—the airframe parts and pieces—should last the better part of a century. Along those lines, the things used by pilots to see through portions of the airframe, the windows, generally have a useful life measured in decades.

I’ll note here that the windows on your airplane probably aren’t glass, they’re acrylic, though I’ll sometimes use “glass” as a shorthand term. The enemies of acrylic windows are sunlight, dust, chemicals and scratches.

John Zofko Jr., founder of Great Lakes Aero Products, one of the big three aircraft window manufacturers, told me that a reasonable expectation for the life of the windows of an airplane that is hangared is 30 years. If the airplane is tied down, plan on 10-15 years. Scott Utz, proprietor of Arapahoe Aero on Denver’s Centennial Airport, advised me that, in his experience, aircraft tied down at high-altitude airports, with their more intense sunlight exposure, need window replacement near the bottom end of his estimated life span. In addition, the longevity of acrylic depends on how it’s treated.

When to Replace?

Your glass should tell you when it needs to be replaced. Crazing, which is just a lot of little cracks in the acrylic, and milkiness, the whitening that comes from exposure to sunlight, affect your ability to see out of the airplane. Aging glass will manifest itself to you when flying into a low sun or at night. That becomes a hazard—you can’t see obstructions and may be unable to safely make a landing or takeoff into a setting or rising sun.

In addition, don’t think that crazing is a cosmetic matter that you can ignore by flying only when the sun is high—those cracks that create the effect also are weakening the acrylic.

Delaying replacement can have serious financial repercussions—the sealant around the glass deteriorates and/or windows simply loosen up in their frames with the passage of time. That means rainwater will seep inside the airframe—creating a high probability of corrosion. This is of particular concern on older Mooneys, but certainly isn’t limited to that marque.

There is almost no guidance on what is acceptable wear and tear on the windows for unpressurized airplanes built before the late 1990s. The manufacturers provide no criteria as to service limits, so one has to look to FAR Part 43.13’s inspection criteria—and it’s nearly silent on the subject.

Later airplanes have published tolerances regarding crack lengths and locations on windows, but deal with crazing and milkiness by providing guidance on clarity and line of sight and deferring to the judgment of maintenance technicians.

What’s Available

There are a surprising number of options available for replacement glass. In many cases you’ll be faced with a choice of tint colors (or no tint) and, in many cases, a range of thicknesses.

Depending on the vendor, color choices may include clear, green, gray, bronze and blue. Figure on a 20 percent and up price bump for tinted glass. During my search of options, I saw tints that allowed transmission of as little as 10 percent of ambient sunlight—but only for the side windows behind the pilot. For the windshield and front windows, there is a safety issue. FAR 23.775 specifies a maximum degree of tint—the acrylic must allow a 70 percent or greater light transmission. Manufacturers measure that with a light meter.

UV and IR Blocking

One of the more exciting developments of the last 20 years is tint that blocks ultraviolet and infrared radiation. These are touted—accurately, from firsthand observation—to reduce the very real risk pilots face of skin cancer and eye damage that comes with flying. The IR and UV blocking tints should also reduce damage to interior plastics and fabrics, as we’ll as keep solar heating of the cabin down. Ordinary tinting does not block UV and IR radiation.

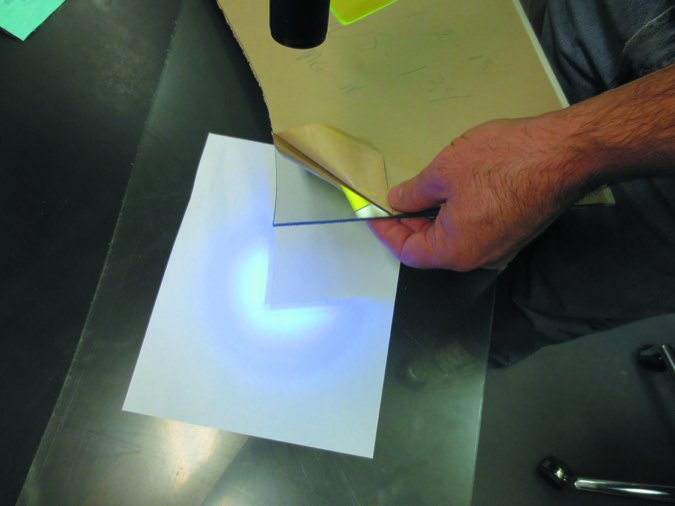

During a visit I made to Great Lakes Aero Products, a UV light was shined through windshield material onto a piece of paper. As shown in the photo on the next page, the paper fluoresced. As also shown in the photo, the SG (solar gray) tinted acrylic dramatically reduced UV transmission.

The UV and IR blocking tints are 25-75 percent more expensive than untinted glass.

Thickness

Increasing window thickness reduces cabin noise. In testing Aviation Consumer did in a Mooney in 2007, measurements showed that cabin noise level was reduced from 1-3.5 dB, depending on the location within the cabin.

A side benefit to a thicker windshield is strength. While I could find no test data, I did read accounts of airplanes with relatively new, thicker replacement windshields withstanding bird strikes that may have broken through original-thickness windshields.

Depending on the airplane, thicker glass may need to be milled around the edges to fit in the opening designed for thinner glass. In some cases a thicker window can be ordered from the manufacturer; however, the manufacturer may expressly indicate it does not recommend that particular installation.

Increased thickness adds about three pounds to the weight of a full set of replacement glass.

Clear (Untinted) Windshield Select Price Comparisons by Thickness (Inches) | |||

AIRCRAFT | LP AERO Plastics | GREAT LAKES AERO PRODUCTS | CEE BAILEY |

BEECH V35A BONANZA | $1357 (0.250) $1989 (0.312) $2166 (0.375) $2592 (0.500) | $1081.84 (0.250) $1587.70 (0.375 outside milled) $1729.04 (0.375 inside milled) | $849 (0.250) |

1969 CESSNA 172 | $630 (0.125) $683 (0.187) | $502.77 (0.125) $504.13 (0.150) $505.50 (0.187) | $528 (0.250) |

1970 cessna 310q | $1645 (0.250) | $791.63 (0.250) | $682 (0.250) |

1973 piper archer (two-piece windshield) | $252 each (0.125) $274 each (0.187) | $193.48 each (0.125) $220.73 each (0.187) $249.34 each (0.250) | $168 each (0.125) $205.85 each (0.250) |

1975 Piper Seneca II (two-piece windshield) | $228 each (0.125) $262 each (0.187) | $218.00 (0.125) $249.34 (0.187) $316.10 (0.250) | $225 each (0.125) $271 each (0.250) |

The Replacement Process

The process of replacing glass means doing what is necessary on the airframe to get at the existing glass—that may mean anything from simply folding back or removing interior fabric or plastic to a major excavation chore on some composite airplanes. The glass is removed, the area cleaned up so there will be a good seal with the new installation and the new glass installed.

As I was doing the research for this article I was impressed by the amount of information made available by the window manufacturers for those who are doing the installations. I also noted that in many cases, it’s necessary to provide the manufacturer with the aircraft serial number to ensure it gets the correct glass and fit as the aircraft manufacturers often made small changes over the course of production of a particular model.

The method of sealing the windows varies with the manufacturer. Cessna uses a felt seal that must be replaced with the window—the seal itself can wear out. According to Scott Utz, it’s not unusual to see windows that are loose within their mountings because the seal is gone. Piper’s felt seal is similar to Cessna’s. Beech uses a permagum seal that is akin to strips of caulk. Cirrus has a sealant that is similar to fuel tank sealant and easy to work with.

How Long Does it Take?

Shops I spoke with gave ranges for glass replacement. For a Cessna 172, figure on a windshield install to run 24-30 hours; all glass 50-60 hours. The 172 windshield is tricky—both to make and to install—because of all the compound curves.

A Piper Arrow windshield runs six to eight hours total; it can be done in a day. All glass usually takes about 20 hours. Piper is the easiest to replace because just a little bit of the interior needs to come out.

In general, older Mooneys are easier than newer—the newer, cleaner airplanes have more bodywork to deal with.

I was told repeatedly that the most difficult glass work is on composite aircraft—particularly on the Cessna 350 and 400. An owner should figure on 100 hours for the windshield and 40 for each side window. The glass is put in place from the outside, the special glue used has to be heated and then kept at temperature for several hours, and cosmetic work including body filler has to be done and the area painted.

At the other end of the composite spectrum, the Cirrus series has glass that is fairly easy to replace—for a composite airplane. The work is all done from the inside.

I heard some horror stories of inexperienced shops that either spent an inordinate amount of time on installations, did them poorly or couldn’t do them at all. My suggestion is to make sure your shop has installed glass on your type of airplane.

Care

Whether you are dealing with new replacement glass or your existing acrylic, the care is the same. Do not use any harsh chemicals or ammonia-based cleaners when cleaning the acrylic—I was told of people who used lacquer thinner, wood alcohol and abrasives to clean their windows and then were puzzled as to why their windows became nearly opaque.

The manufacturers recommended mild dish soap mixed with water and rubbing the window with one’s bare hand (no jewelry) as the best method. If a cloth is used, it should be soft and non-abrasive. The manufacturers’ websites have good information on cleaning and protection.

The May 2015 issue of Aviation Consumer had a review of windshield cleaning products that offered both cleaning and rain protection—Plexi Klear, All Klear and 210 were the top picks.

Covers and Shields

For protecting the windows and windshield, some shops I spoke with liked external covers; others didn’t like them at all. Everyone agreed that if used, they have to be tight and keep dust out. A cover flapping in the wind will damage acrylic quickly, especially if there is any dust under it. The chemicals used to bond the interior material to the outside cover of some will migrate through the cloth to the acrylic and damage it. Sewn rather than bonded covers were recommended.

I received conflicting recommendations on sunshields. Some told me that they hasten acrylic deterioration because the UV rays go through the glass and then are reflected back out, doubling the effect. Shades should not have any metal surfaces that come into contact with the acrylic.

Conclusion

Window and windshield replacement is a fact of life for aircraft owners who cannot hangar their airplanes. The price of the replacement glass is almost always less than the cost of the labor for the replacement—so the savings gained in selecting a shop that has experience doing the work on your type of airplane may allow you to buy UV- and IR-radiation-blocking acrylic and could pay off in a longer life for the interior and you.

We think the benefits of an exterior cover or interior window shields exceed the risk—just make sure your cover doesn’t flap or have dust under it and that your window shields don’t have anything metallic touching the acrylic.