The idea behind the light sport aircraft rule was to stimulate new designs at affordable prices. “Affordable” is arguable, but the new designs are out there in such volume that few models have been able to rise above the noise as standouts.

The latest effort comes from a new company called Texas Aircraft with a design called the Colt. Priced at $167,000, the aircraft itself is what you’d expect of an LSA-100-knot cruise, adequate climb, sub-500-pound payload and a price that puts it in the middle of the light sport spectrum. A basic Colt model, the S, sells for $10,000 less.

So in a market already choked with more choices than even the most diligent buyer can sort through, how can a late entrant hope to distinguish itself from the crowd? Texas Aircraft appears to be charging into the market with a two-place LSA that aspires to eventually achieve Part 23 certification and a follow-on four-place model, an ambition expressed by at least one other manufacturer-Flight Design-but thus far not achieved. Yes, Tecnam is noted here, but Tecnam began life in the world of certified aircraft and morphed downhill into the ultralight/light sport world.

From Brazil

Brazil has been a hotbed of aviation activity, especially during the past three decades. With the state-owned Embraer, Brazil became the number three producer of commercial aircraft behind Boeing and Airbus, and the former recently bought an 80 percent stake in Embraer.

Brazil has also spawned a handful of light aircraft manufacturers including a company called INPAER, whose chief designer and founder, Caio Jordo, is we’ll known in Brazilian aviation circles. Although the company considers it a clean-sheet design, the Colt clearly springs from INPAER’s original Conquest 180. That airplane was designed in the early 2000s in the spirit of the U.S. light sport rule, but it was never approved nor imported into the U.S. as such.

The basic airframe served as a developmental test bed, however, and eventually morphed into a three-place variant and even a four-place model. These sold in some numbers in Brazil under a murky set of regulations that, according to Jordo, allowed what were essentially experimental aircraft to be sold as ready-to-fly products to end customers. It was a carve out of sorts because Brazil’s regulatory structure had no way to accommodate the amateur-built airplanes that owners were in fact buying and building.

The response was a regulatory stopgap that allowed manufacturers to build ready-to-fly aircraft that weren’t EABs but weren’t certified either. And that’s what INPAER did with the Conquest until Brazil’s regulations were brought more into line with the rest of the world. Somewhere north of 300 aircraft were built, a mix of two-, three- and four-place models.

Jordo says the Conquest is no longer being manufactured nor sold in Brazil, although INPAER still exists to support aircraft in the field and may eventually serve as the portal to import the Colt from the U.S., either as an ASTM airplane or a Part 23 model, if it gets that far.

The Colt can be thought of as Conquest V2.0 and Jordo, buoyed by outside capital investment from Brazil, established Texas Aircraft in Hondo, Texas, specifically to sell into the U.S. light sport market.

The company launched in 2017 but only recently began manufacturing in volume. When I visited the factory in mid-July, several aircraft were in the works and the company was expecting final FAA approval for its ASTM compliance. The word “certification” is often used to describe this process, but it’s a misnomer. LSAs are approved under ASTM consensus standards, not type certificates.

Plastic To Metal

While Jordo’s Conquest began life as a composite airplane with fabric wings, it eventually evolved to have all-metal, strut-braced wings. The Colt has evolved further into a metal, riveted design, but has retained the high-wing strut-braced approach. Through translator Caio Braga, Jordo said that while the Colt is informed by the Conquest, it has been modified considerably.

The wing was redesigned to improve the stall characteristics and the cabin is somewhat larger to improve the ergonomics. Although it’s not common to see manufacturers switch from composite to metal or back, that’s what Jordo did with the Colt.

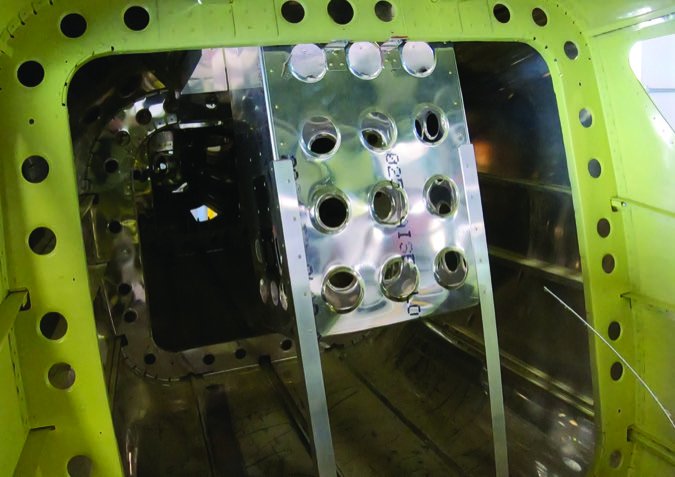

He said metal penciled out to be more easily manufacturable and more structurally efficient. And with access to sophisticated CAD-CAM equipment ever more affordable, capital requirements are lower than ever for metal manufacturing.

Design wise, the Colt is largely conventional in the manner that a Mooney is conventional. It shares the Mooney’s marriage of a welded chromoly cage around the cabin area to a conventional monocoque section aft of the two seats.

The wings are similarly all metal and incorporate fuel tanks in the wings for a total usable capacity of 31 gallons with a left/right/off switch on the cockpit console. The control circuitry has tubes inside the cockpit that terminate in bellcranks connected to cables to move the control surfaces.

As is the fashion for most light aircraft systems these days, the trim system is electric-only driving an elevator-mounted tab. The flaps are also electric and although they’re continuously variable, the POH recommends two positions: half flaps for takeoff and full for landing. While most manufacturers have adopted Rotax’s fuel-injected 912 iS, the Colt retains the 100-HP 912 ULS. Jordo said that the Colt’s design brief was simplicity, reliability and ease of maintenance and that’s why he stuck with the ULS. That engine is also lighter and less expensive than the iS, although it’s debatable whether it’s easier to maintain. The 912 ULS’s carburetors require attention and we’ve heard owner complaints about this.

Cabin Comfort

Another complaint we’ve heard is that LSA cabins are tight and, oh, by the way, they have anemic payloads. In the Colt, Texas Aircraft addresses the former but not the latter. The specs give the cabin width as 42 inches or fully four inches wider than a Cessna 150. It feels that way, too. There’s no shoulder bumping for normal-sized people and probably enough room for those of wider girth.

There seems to be little penalty for larger frontal area because the airplane, although not fast, is slippery. A nice touch is seats that actually slide fore-and-aft on rails instead of rudders that adjust or seat cushions that swap. The seats themselves are luxe by LSA standards and the leather-covered yoke imparts a high-end sport sedan feel, even for those of us who think all light aircraft ought to have sticks instead.

My only complaint about the ergonomics is the cabin height. It’s 44 inches, but that’s not the problem. Once you’re in the airplane, there’s generous headroom. The problem is getting in because the door has an upper sill that forces you to duck to ingress. It proved only a slight problem for my 5-ft. 8-in. frame, but taller pilots or those long of torso may struggle.

At 836 pounds empty, the Colt has 484 pounds of useful load. That’s two 200-pounders and 14 gallons of gas. That’s fine for a training flight, but not so fine for cross- country flying where you might also wish to carry some baggage. So if you carry full fuel, the people better not weigh more than 300 pounds total.

The baggage area is generous-38 by 22 inches with a 44-pound limit. The floor of it is bisected by a narrow rectangular tunnel that houses the elevator and rudder control circuitry, rather like the driveshaft tunnels in 1950s cars. While that can help organize the baggage compartment, it will also prevent larger objects from lying flat on the baggage compartment floor.

Even in the surface-of-the-sun temperatures of a Hondo, Texas, summer, the cabin proved surprisingly comfortable. Taxiing with doors open kept the heat at bay and in flight, a pair of adjustable scoop vents in the windows provided a cooling rush of air.

Avionics wise, Texas Aircraft installed Dynon’s SkyView HDX, a well-wrought, easy-to-use EFIS system that’s a good match for the airframe. It also has the Dynon two-axis autopilot, comm radio and ADS-B Out. The system has a level button, but no active envelope protection.

The version I flew had steam gauges in the right panel, but production versions won’t need that, nor will discrete engine instruments be needed. The Dynon’s engine monitoring function, which is excellent, will handle that.

Flying It

Since I haven’t flown the original Conquest 180, I can’t say if the Colt iteration is a better handling airplane. But in the absolute, it’s a first-rate handling airplane, in my estimation. A persistent complaint I have about light sport aircraft is too-light control forces. Some are dangerously too light, in my view.

The Colt has none of that, either by dint of the yoke or the control pivot points and design. In roll, it’s pleasantly heavy-about like a Cessna 150, I’d guess. Pitch is lighter, but not to the point of twitchiness. On takeoff, I noticed no tendency to over-control or PIO because of lightness. Also, it requires little trim fussiness; trim it once and it seems to stay put. Flap deployment hardly musses its hair.

Performance is LSA-predicable. On a hot Texas day, it climbed at about 800 feet initially and easily held 600 FPM as it got into cooler air. The promo specs say 110 knots at 75 percent power. I didn’t see a number that high, albeit it on a hotter-than-standard day. At about 5000 feet, the Colt settled out to 101 knots at just over 5 GPH.

Frankly, I’d be surprised to see anything different, given that light sport airplanes are designed to cookie-cutter specifications. With 31 gallons available, the airplane has a typical 550-mile still-air range. It’s comfortable enough to contemplate staying in it that long, too.

If the Colt ever evolves to become an instrument trainer, it will make the pilot’s life easy. In pitch, the airplane is heroically stable, damping an intentional phugoid in a single cycle with no drama. It tends not to depart in a hands-off turn and is happy to fly along level with hands off.

The stall is benign, even when aggravated. I found that like other LSAs, it has a pronounced parachute mode if the elevator is held full back after what passes for a stall break is achieved. The descent rate varied from 150 to 900 FPM and while the nose bobbles, I used only slight rudder pressure to keep the nose from yawing off into a spin entry. The airplane isn’t approved for spins, but I suspect it would recover normally.

For the first landing, demo pilot Humberto Vivanco suggested 65 knots, which turned out to be way, way too fast. (It’s 1.7 Vso.) For a strut-braced airplane, the Colt is slick and doesn’t want to slow down. In subsequent landings, I tried 50 knots and still floated a bit. With practice, 45 knots over the fence might not be too slow. It handles forward slips nicely, too.

Conclusion

So where does the Colt fit in a market glutted with choices? Does it fit at all? Pricewise, it’s closer to the top tier than the bottom. Consider that the CubCrafters Carbon Cub typically invoices for more than $200,000, but the recently introduced Vashon Ranger, at $115,000, is just more than half that. So at $167,000, that puts the Colt closer to the top tier than the bottom.

While I see the logic of equipping with a 912 ULS rather than the iS, I think the industry needs to get past carburation in new airplanes and move to ECU-controlled fuel injection. Cars have been there for 30 years. Market reaction will tell Texas Aircraft if buyers want the iS, but I certainly would, even at the expense of additional weight.

I know it will offend some to hear this, but the LSA weight limit is the most widely abused limitation in aviation. In any case, the Conquest flew at a gross weight of more than 1600 pounds, so it has the structure.

The Colt’s performance is workmanlike, but not exceptional. If it stands out at all, my view is that it’s a little airplane masquerading as a big one. The ergonomics are excellent and the handling is we’ll sorted, especially if the airplane finds a home as a trainer. Teaching landings in it would be a blast.

Given the sales success of INPAER’s four-place designs in Brazil, the Colt may be more a means than an end, since the company plans to evolve it first into a Part 23 airplane and later into something with four seats. In a couple of years, we’ll know if they’ve got a good start.