Spend a short time with a Quest Kodiak 100 on the ramp and inevitably someone will call it a Cessna Caravan. Granted, they’re both PT6A-powered high-wing haulers that stand tall and burly, plus they can both carry water floats and cargo pods. But look more closely (better yet, fly it) and it’s obvious the Kodiak is unquestionably its own airplane.

The latest Kodiak 100 Series II has a change in personality from earlier versions, which in my view lacked some refinements that buyers expect in an airplane that’s north of $2 million, and closer to $3 million when equipped with the Aerocet two-piece carbon fiber amphib floats. That’s the configuration I spent a day flying off the pavement and the water for this report.

Clean Sheet, Modern Bush

Sandpoint, Idaho-based Quest Aircraft says the Kodiak came to life (during the late 1990s) to fill the need for a modern-day bush airplane. Initially sketched on the back of a napkin by its two company founders, the Kodiak’s first flight was in 2004 and it earned FAA Part 23 type certification in 2007, 32 months after its first flight.

A clean-sheet design with STOL capability, the Kodiak initially catered to humanitarian groups that needed to get in and out of tight and unimproved strips. It carries a sizable payload (upward of 3500 pounds and roughly 2500 with floats), seats up to 10 people and most important, it runs on Jet-A for operating in places where 100LL is impossible to get, and of course to up the ante in reliability and operating simplicity. Quest chose the 750-HP Pratt & Whitney PT6A-34. It has a 4000-hour TBO—which at the time was the most widely produced single-stage variant of the PT6A—making worldwide field support even easier.

A talking point during prospective Kodiak 100 sales demos is the -34’s lower overhaul cost, compared to other variants. But make no mistake, overhauling any PT6A is a major event. The current Aircraft Bluebook says a typical overhaul including installation is around $240,000. Check that against the Pratt -114A variant used on the Cessna 208 Caravan. A typical overhaul for it is around $250,000 and the TBO is shorter, at 3600 hours.

The Kodiak’s engine is tuned to operate at lower altitudes and optimized for ops in the 12,000-foot range, where the unpressurized, fixed-gear airplane spends most of its time. Its certified max operating ceiling is 25,000 feet.

The Kodiak has a wet-wing design with a 320-gallon fuel capacity, and there’s now an STC’d single-point fueling option, located at the left wing root. All of that fuel is stored behind the main spar, creating a fire-resistant crumple zone in front of the occupants. There’s also a clever magnetic under-wing fuel measuring dipstick, which makes verifying the fuel status—and cross-checking the Garmin G1000 NXi’s digital computations—a snap.

Oodles Of Storage and A Unique Wing

The Kodiak has a big 49 by 49 inch cargo door that was designed for loading pallets. The door folds down flat for easy forklift access, plus it functions as an air stair for loading the passengers. The cabin is 48.5 inches wide and nearly 50 inches high. That’s not a stand-up cabin, but it’s spacious, especially when equipped with the executive interior. The cargo volume is listed as 248 cubic feet and there are cabin doors (one on each side) for climbing into the cockpit.

For more utility, on wheeled versions there’s an optional composite external cargo compartment (ECC), which has a has a maximum load-carrying weight of 750 pounds and a max floor loading of 65 pounds per square foot, enabling a variety of loading scenarios. The ECC is divided into three compartments with internal anti-skid flooring (each with an individual door), and each compartment is separated by composite bulkheads. While the ECC looks like it might rob a sizable amount of performance, the airplane only loses a couple of knots in cruise thanks to its aerodynamic design.

There’s also a 29-inch tire upgrade for better handling and durability when operating off unimproved strips. This increases the aircraft’s landing weight to 7225 pounds. The fixed Cleveland landing gear is of a faired leg design with no wheel pants. The mains are spring steel and the steel nosegear is air-Oleo.

There’s a gravel/mud deflector that attaches to the gear to minimize the slinging of rocks and other debris onto the bottom of the wings, fuselage and horizontal stabilizer.

What makes the Kodiak different than most other turboprop singles is the wing design, which marries two wings into one. There’s a notch in the wing’s leading edge, which Quest calls the discontinuous leading edge. That’s the area of the wing that doesn’t stall. Pull the power lever back to zero thrust, haul back on the yoke and the outboard section of the wing doesn’t stall. That means full aileron control and no change in roll rate in a stall—it’s pretty remarkable.

New to the Series II Kodiak, in addition to the three-screen Garmin G1000 NXi (an upgrade from the plain-vanilla G1000 used in previous models), is Safe Flight Instrument’s angle of attack indicator. The system uses an indexer that mounts on top of the glareshield and has audible and visual cues. Stall speed with the single-slotted Fowler flaps up is 77 knots and 60 knots with the flaps down.

The airplane I flew had the optional TKS ice protection system installed, but it’s disabled when the floats are installed. The system has a 16-gallon de-ice fluid tank for 2.5 hours of continuous operation in normal icing conditions. The system makes the airplane approved for flight into known icing.

Standard, of course, is mandate-compliant ADS-B Out via Garmin’s integrated 1090ES transponder. There’s also active traffic and terrain alerting, and new to the Series II is the GWX70 weather radar. The standard GWX70 version has four-color storm cell tracking and side-view vertical scanning to profile cell buildups and storm tops. As an option via an enablement card, there’s turbulence detection and ground clutter suppression—which identifies and removes ground returns from the display.

Modern Floats

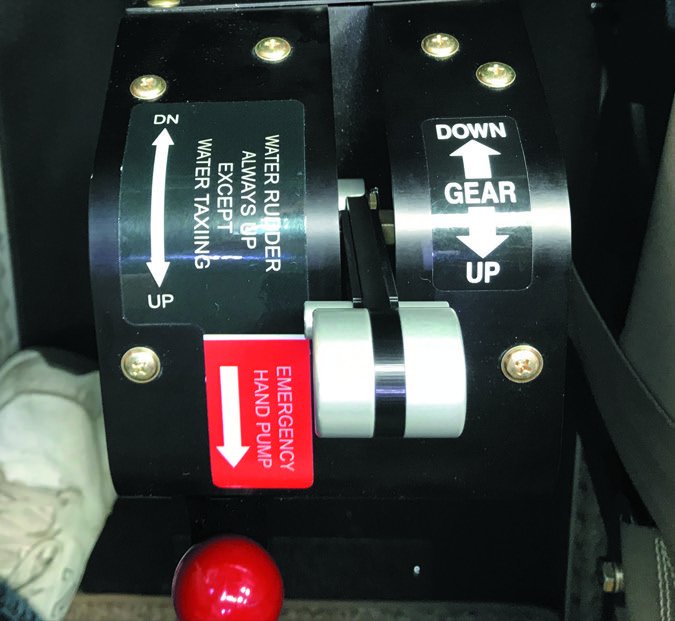

The Kodiak 100 I flew was the first one fitted with the Aerocet model 6650 two-piece carbon composite amphibious floats. The Aerocets weigh a touch over 1200 pounds (maximum flotation is 7406 pounds) and come standard with a gear advisory system with audible announcement for gear positions and “check gear” warning callouts. There’s an annunciator that shows when the hydraulic pump is running and the digital control head shows the status for each gear wheel and its position.

There’s also built-in hydraulic over-pressure relief, while the reservoir and sight glass are built into the hydraulic power pack so you can get a quick read on the fluid levels.

The floats have nine watertight compartments and six storage lockers with large access doors and high-end hardware that makes it easy to tell when the doors are secured. The floats have molded steps for climbing aboard.

Quest Aircraft’s Mark Brown told me the floats are impressively watertight, and that’s partly because there are no rivets. “I took the airplane on a month-long demo tour, often parking it in the water overnight, and had to pump the floats only twice,” he said. The two-piece molded composite construction also means no corrosion.

A big advantage of the Aerocet 6650s, which are the largest and only composite floats on the market, is the weight savings. They are 400 pounds lighter than equivalent metal floats, saving weight for more people and fuel.

But modern design and efficiency comes at a price. The Aerocet 6650s add an eye-watering $399,000 to the cost of the Kodiak 100, including the installation hardware. Kodiak also offers the Aerocet 6750 straight floats.

Flying It

The Kodiak 100 has a maximum takeoff weight of 7255 pounds and with the Aerocet floats installed, it’s a big aircraft to operate around the airport surface. For water ops, there’s an option for a pitch latch propeller. This allows the propeller to stay in a fine-pitch position when the engine is shut down. When you start it, this takes less time to get the airplane away from the dock and taxiing on the water.

A wheeled Kodiak has a 934-foot takeoff ground roll and a published 1340 FPM climb rate. Typical climb speed is around 88 knots. On floats with a strong headwind, 500 pounds of fuel and four average-sized adults on board, we were off the runway at Windham Airport in Eastern Connecticut and into the climb in we’ll under 1000 feet.

Since the PT6A engine isn’t FADEC controlled, you do have to be especially mindful when setting the power and vigilant in not overtorquing it—a pricey blunder that requires an engine teardown. But, the engine actually has up to 900 HP available should you get yourself into trouble on the water or on land and push the power lever to the firewall, which would overtorque and over-temp the engine.

As for performance, you’ll sacrifice roughly 20 knots of cruise speed and a couple hundred FPM of climb with the Aerocet floats. The book says maximum cruise performance on wheels is 183 knots. At a 174-knot cruise speed in no-wind conditions, a Kodiak without floats or a cargo pod has a range of 1005 nautical miles with 45 minutes of reserve fuel at 12,000 feet.

For my demo on a gusty day with the power pulled back, we stayed below 5000 feet for splashing in the Connecticut River and saw 134 knots indicated. But for going places, you’d likely climb up to 10,000 or 12,000 feet, where the Kodiak would clip along at 160 knots true—hardly shabby for anything carrying big floats. Expect to burn around 350 PPH (58 GPH) of Jet-A.

Contemplating my first water landing in the Kodiak (with whitecaps visible in the river), I asked Brown about the typical transition experience for competent seaplane pilots coming out of smaller piston-powered aircraft. According to him, transitioning to a Kodiak 100 on floats is quite different because it’s a turboprop. He’s right.

Having earned my seaplane rating in a Cub on floats, but having logged time behind a PT6A, it took some time to get over the Kodiak’s size. It stands real tall on the Aerocets and like flying any large airplane for the first time, judging when the floats will touch the surface was tricky. Moreover, the long snout can pose some challenges on the water. For example, in a piston seaplane you can generally nose into a dock, but that might not be an option in the Kodiak. And, when you shut down the engine when approaching the dock in the Kodiak, the prop will windmill. It stops right away in a piston, of course.

But saying all that, the big Aerocets are quite forgiving when touching down—and going around—because of their large sweet spot. With Brown calling out power settings (while his hands hovered centimeters from the controls), I was getting the hang of putting the Kodiak on the rough water. In jet airplane fashion, I especially like that the automatic trim runs after you deploy the flaps, even when the autopilot isn’t engaged.

The floats are slippery in the sense that you hardly feel abrupt acceleration when the aircraft leaves the water. I was also impressed at how quickly the floats got onto the step. For tightly confined water ops, it’s real easy to get used to 750 HP, as long as you’re aware of the turbine spool lag.

Back on pavement, the Aerocet’s trailing link main gear with Oleo shock system makes for smooth touchdowns. The advertised landing ground roll is 765 feet and yes, pull the prop into reverse Beta to get the airplane stopped quickly.

Testing A New Market

With excellent fit and finish, the Series II Kodiak 100 is a different airplane than it was in earlier generations thanks in part to a more refined and sophisticated cabin dwelling. There’s more soundproofing and also inflatable door seals that make it quieter, plus you don’t smell the jet exhaust that makes its way into the cabin as you do in earlier models.

The cabin has good lighting with high-end fixtures, comfortable seats and modern amenities (USB ports, for example) that every buyer is likely to expect. The Series II is equipped with Garmin’s Flight Stream wireless hub for tablet connectivity.

Clay Lacy Aviation, Quest’s Northeast dealership, is trying something interesting with Kodiaks by adding them to its charter ops to complement its fleet of 100-plus jets. For jet setters who want transportation to or from New York City’s East River to the Hamptons, as one example, a Kodiak on floats is up to the task. Quest is also adding to its network of domestic and international dealers to support the Series II and the 200-plus aircraft in service.

The new Kodiak 100 starts at $2.15 million and nearly $2.8 million with floats and popular options.

Visitwww.questaircraft.com.