The Piper Navajo occupies a unique niche among piston twins: it has found a substantial market in the commuter airline business while retaining an appeal for owners who want to fly themselves in relative comfort and luxury. Cessnas 402 is another such twin but you don’t find many of those in private ownership.

The PA-31 was produced in a half-dozen variants spanning two fuselage sizes over a 17-year production run beginning in 1967 and ending in 1984. All told, just over 1500 were built, the lions share of them the long-fuselage Chieftain version. Many of these have found their way to Europe and the Pacific, where they are valued as commuter airliners.

Piper had to earn its bones in this market, since it had no experience in large commercial aircraft working the airline service cycle. The experience paid off, however: it led directly to the development of more sophisticated airframes, such as the Cheyenne.

Owners of Navajos tell us they love the airplanes but, as with any twin, these airframes simply cant be flown on the cheap. They require ongoing maintenance, the engine overhauls will consume much of $100,000 and the airframes virtually swim in ADs. That said, one owner sums up the Navajos appeal this way: The Navajo is a fine aircraft, capable of performing many missions. It is comfortable and stable, straightforward to maintain and operate, reliable and cost effective. Our passengers don’t groan when boarding.

Model History

When the first Navajo appeared in 1967, it debuted with the likes of the Cessna 401 and 411. The high-class 421 came out a year later. Although Cessna had big-twin experience, Piper didnt, having been focused on airplanes like the Apache, Comanche and Tri-Pacer. Originally named the Inca, the PA-31 evolved from a relatively small twin into a large six-to-eight-place model which was we’ll received.

Initially, there were only two windows in each side of the fuselage aft of the cockpit, but this was increased to three rectangular windows with a smaller triangular one on the aft starboard side. The basic shape and arrangement held through the production life of the Navajo, yielding a cabin size almost large enough to stand up in.

The prototype flew in September, 1964, powered by variants of the Lycoming O-540 family that remained the powerplant of choice throughout the Navajo production run. The first model year had both normally aspirated and turbocharged versions. The launch model was the PA-31-300, powered by 300-HP IO-540-Ms with two-bladed propellers and a recommended TBO of 2000 hours, a bit better than the Continental engines used in the Cessnas.

While the 300 has the same 190-gallon standard fuel capacity as all un-pressurized Navajos, max takeoff weight is 6200 pounds, compared to 6500 for all the other so-called short-body Navajos, while basic empty weight was only 156 pounds less than the turbocharged version.

The 300s production run was stunted: Only 14 were built over two years. The so-called 310 is really the standard Navajo. With turbocharged 310-HP engines, it could fly 30 knots faster, its single-engine ceiling was higher and it could take off shorter, plus, of course, the aforementioned extra useful load. This additional performance cost, on an average-equipped airplane, less than $10,000 on an invoice totaling about $130,000. Its easy to see why the 300 was dropped.

While some initially were designated PA-31-310 and called the Turbo Navajo, the FAA issued an AD in 1973 requiring that any called that have the data plate changed to a PA-31 model designation. Despite early problems with the turbo system, this is the second most popular version of the Navajo.Improved B and C models were introduced in 1971 and 1975, respectively. Radar appeared during this period, along with deice systems, although not all airplanes have it and some that do arent certified for known ice.

As a nod to working pilots flying a working airplane, the pilot got his own overwing hatch so he wouldnt have to clamber over the cargo and passengers to get to work. In later models, the door was enlarged.

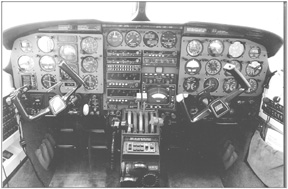

A number of refinements to systems were made along the line and not all are identified by changes to model designation. Field experience and maintenance issues were applied in a number of ways, such as improving the electrical system, including the location of circuit breakers and isolating wiring runs from sources of chafing and other deterioration. The cockpit was improved over the years, as was the appearance, comfort and serviceability of the cabin interior. When shopping Navajos, don’t be surprised to find wide variation in interior appointments.

A three-bladed propeller was offered as an option with the B model and made standard with the C. While many pre-1979 Navajos are equipped with some or full deice equipment, approval for flight in known icing (described at the time as approval for flight in light to moderate icing) was not obtained until the 1979 model year. Recommended TBO increased from the initial 1500 hours to 1800 hours. Also, there are special conditions under which this now can be extended to 2000 hours. This requires trend monitoring and approval from the FAA, for for-hire operations.

P-Navajo

The PA-31P (a/k/a the PA-31P-425, or P-Navajo) was introduced in 1970. It was the most sophisticated, highest-performing Piper ever, with a big but troublesome, geared version of the 540 series engine, the TIGO-541-E1A. The pressurized Navajo was cured of early problems with the pressurization system, but powerplant reliability has continued to plague the ambitious design.

Initial recommended TBO of the 425-HP engine was an appalling 800 hours and even now, its only 1200 hours.

Plan on spending $45,000 each for the overhauls. A high-ticket, short-TBO engine is a major cost factor in any airplane so owners of this model should budget $70 an hour just for engine reserve. Combine this with the fuel burn (mid-20s per engine) and you have a high hourly operating cost. Big engines also mean short range. A standard-fuel P-Navajo has an endurance in the three-hour range with IFR reserves. There was an optional fuel system available, which boosted capacity by 54 gallons.

Production of the P-Navajo ended in 1977; a total of 259 were built. Prices on the used market range from about $120,000 to maybe $180,000, reflecting the high maintenance load. To put this in perspective, a Turbo Navajo of comparable vintage is likely to be worth $20,000 to $40,000 more, despite having 115 HP less per engine and no pressurization.

Chieftain

The largest and most successful Navajo, the PA-31-350 Chieftain, was introduced in 1972 as a 1973 model. The fuselage was stretched two feet (ahead of the wing) and the tailplane span increased. The cargo door was made standard. The power comes from counter-rotating L/TSIO-540-J2BD, 350-HP engines.

The floor was beefed up and an additional window added to each side of the fuselage. Up to 10 seats could be fitted. Empty weight increased by roughly 200 pounds and maximum takeoff by 500 pounds.

Extended nacelles provide baggage capacity and/or optional fuel tanks. The option raises total usable fuel from 182 to 236 gallons. The initial TBO of 1200 hours was increased to 1600 in 1979 and then 1800 (it, too, can be stretched to 2000 under special conditions). These engines cost about $30,000 each to overhaul.

Performance of the Chieftain is not too far off that of the P-Navajo despite having less power. Combine this with the bigger cabin, less costly and troublesome engines and significantly more range through higher efficiency and its easy to see why the Chieftain was so popular despite its lack of pressurization.

The T-1020 (model designation PA-31-350-T-1020) was an attempt by Piper to gain a larger foothold in the airline market. Called by some a stripped Chieftain, the powerplants were the same. It featured beefier components where experience showed weaknesses, especially elements affected by high cycles, such as doors, landing gear and gear doors. The interiors are also more durable. Up to 11 seats could be installed. Introduced in 1982, a total of 21 T-1020s were manufactured, making it a rare airplane; we found no cost data on it.

Navajo C/R

The PA-31-325 was introduced in 1975 as yet another iteration of the shortbody fuselage. C/R means counter-rotating, reflecting the counter-rotating L/TIO-540-F2BD engines rated at 325-HP each that Piper selected for this model. Like the Chieftain, the C/R has extended nacelles with baggage lockers that can be used for additional baggage space or optional auxiliary fuel tanks.

Empty weight averages 90 pounds more than the basic PA-31. Cruise speeds are marginally higher, but range is marginally lower. Single-engine performance is improved although not noticeable when flown by the average pilot. According to the book, the basic Navajo has better takeoff and landing performance than the C/R.

The supposed advantage of the counter rotating props is more handling ease in the event of an engine failure because-the promotional literature claimed-the dreaded critical engine is eliminated. In our view, this isn’t much of a selling point. In the last year that both the PA-31 and PA-31-325 were offered (1982), the biggest factor was that the latter was about $20,000 more expensive than the straight Navajo. The difference hasnt changed much over the years: The C/R is still worth more than the straight turbo PA-31, by about $15,000.

Mojave

The last Navajo wasnt even called one. The PA-31P-350 was dubbed Mojave. It was a hybrid that reflected lessons learned over the life cycle of the extended Navajo family with a touch of Aerostar influence thrown in. The Mojave has a lot of appealing features, including a dual-bus electrical system, an O-540 variant engine supposedly designed specifically for high-altitude operation that included intercooling and pressurized mags from the factory, and thicker fuselage skins.

The L/TIO-540-V2AD engines are also counter rotating, rated at 350 HP at 2575 RPM and have a recommended TBO of 2000 hours. Overhaul cost is $30,000. Structurally, the wing is based on the Chieftains. Span is four feet wider to improve climb and high-altitude cruise performance. The Mojave, the last twin Piper built in Lock Haven, Pennsylvania, didnt last a year. Introduced in 1983, the 50th and last rolled out the door in June, 1984.

Performance

The non-pressurized Navajo family is surprisingly close in book performance. All have a maximum operating altitude of 24,000 feet. (Forget service and absolute ceilings. This is the limitation that controls operation of the airplane). Speed and range at 65 percent below and at oxygen altitudes are within six knots and 150 nautical miles of each other. Multi- and single-engine rate of climb are so close (100 and 25 FPM at the extreme, respectively) as to be insignificant. So are stall speeds (from 70 to 74 KIAS) and all-engine landing and takeoff field requirements at gross.

The tricky part in performance is payload with full fuel. A corporate-configured Navajo can be carrying between five and six hundred pounds of amenities, particularly if known icing and air conditioning options are included. A bare-bones airline Chieftain, on the other hand, might have 250 pounds or less added to the basic empty weight. So, payload with full fuel can range from a low of less than 800 pounds in a well-equipped C/R to more than 1400 pounds in a Chieftain.

Poorly trained, careless or out-of-currency pilots have found the Navajo, like all light and medium piston twins, to be a wolf in sheeps clothing. It will bite the unprepared. But when all motors and systems are functioning, the Navajo series ranks up there with the absolute best-mannered Pipers ever in terms of handling.

Cabin Comfort

Except for the tallest of pilots, the cockpit is comfortable. The Chieftain is the best of the breed in this respect, because it affords more leg room than comparably equipped and outfitted short Navajos. Visibility is quite good as conventional twins go. Even in the earliest versions, cockpit layout is good.

Passenger acceptance of the Navajo is excellent, according to owners and operators. Entry is eased with the airstair door and in the main cabin, all passengers are treated equally because of the uniform fuselage section and similar seats. The large windows add to a spacious impression.

All things considered, the Navajo offers a good environment for both pilots and passengers. Later models configured for corporate use are downright luxurious. In fact, the least comfortable seat in the house is the one near the main door, due to air noise and drafts.

Support, Maintenance

The Navajo benefits from a fairly large population and a powerplant that continues in production, also in large numbers, thus representing a profitable support business. It is about as far from being an orphan as any out-of-production general aviation airplane could be. And with Piper back on its feet, support is no problem, although some owners complain about slow response from New Piper.

One owner supplied a list of favored suppliers and mentioned he had compiled a list of 60 maintenance and operational points that took some work to identify and to solve. Another mentioned An aggressive preventive maintenance program which involves magneto and alternator overhauls every 500 hours, replacement of the Airborne 400 series pneumatic pumps every 600 hours, fuel injector flow testing and cleaning every 100 hours, engine mount replacement every 400 hours, landing gear lubrication every 50 hours…

Operating care is critical to engine and other system life. Temperature control, from start to shut down, is an important element in care of the engines. Pre-heat, proper warm-up and avoiding rapid throttle movement are simple yet critical factors in engine life. There have been a high number of cylinder problems, especially with the 350-HP engines used in the Chieftain (and the Colemill Panther conversions). Many of these have been attributed to operational causes, such as shock cooling in descent, abuse during training and generally poor technique in day-to-day operation.

In 1982, Lycoming issued a letter covering operational techniques aimed at improving service life. While it focuses on the Chieftain, the information is largely applicable to any turbocharged powerplant. Much of it concerns temperature management, but there are other useful recommendations, such as avoiding partial throttle takeoffs to ensure proper fuel cooling and to avoid detonation. There also are additional maintenance and inspection tips in Lycomings bulletin.

As GA airplanes go, the earlier Navajos are getting old. The usual effects of age are complicated by the fact that the FAA in 2002 added the Navajo series to its Aging Airplane Safety Rule, by dint of the models use in airline service. The long-term impact of this rule is unknown but would-be buyers should know it could lead to expensive, required maintenance of various kinds.

Navajos have a large number of ADs associated with them, including more than their share of repetitive inspection requirements. Make sure that any airplane being considered for purchase is in compliance.

The design-specific (as opposed to accessory ADs) run from flight controls and flight control surfaces to structure and from landing gear to operational and handbook changes. Operational changes included limiting normal and maximum operating speeds at altitude and changes to Vmc for both the PA-31 and C/R.

One of the more notorious ADs limited use of the flaps to avoid strain and the potential for asymmetric flap deployment. It negatively affected the takeoff and landing performance of the airplane. This was addressed by factory and aftermarket changes to the flap transmission and other system improvements.

There are relatively few mods available for the Navajo. The best-known PA-31 mods come from Colemill Enterprises of Nashville, with their line of Panther conversions. These typically consist of a new or overhauled pair of TIO-540 engines, new four-blade Q-tip props and optional winglets. Contact Colemill at www.colemill.com or 615-226-4256.

American Aviation of Spokane, Washington (www.americanaviationinc.com or 800-432-0476) makes intercoolers, which should help out with engine problems by reducing thermal stress. Nayak Aviation Corp. (210-824-7511) sells auxiliary fuel tanks that increase capacity by a total of 52 or 54 gallons, depending on model.

Reader Feedback

I have owned my Navajo for 22 years and have never felt the need to move up. It is reliable, pleasant to fly and is without any nasty tricks waiting to grab you. A Cheyenne would be nice, but the Navajo gets the job done with no muss or fuss.

Anyone contemplating the purchase of a PA-31 should keep in mind that the FAA considers Navajos commuter category airplanes and that in the U.K., they are regarded as sufficiently complex to require two pilots. Regardless of the price paid for a Navajo, a purchaser is taking on a complicated million-dollar machine with costs of operation commensurate with owning a junior airliner.

At last count there were 1620 Navajos of all flavors registered in the U.S. The breakdown is: 437 PA-31-310s; 249-325s and 847 Chieftains. If you can put up with using oxygen up high, the Navajo is the nicest flying piston twin in the sky, equaled only by a Cessna 414A Chancellor. But, the Navajo (without Colemills winglets) will fit into a standard 42-foot wide T-hangar and the Cessna will not.

I have never seen anyone cringe when boarding my Navajo. Passengers love the roomy, bright, airy cabin with its huge windows and comfortable reclining seats.

Navajos demand competent pilots who pay attention to engine and fuel management and gear and flap speeds. In 1982, Lycoming distributed a memo to Part 135 operators containing suggestions on how the engines should be managed. I followed those guidelines and ran the 310-HP engines in my Navajo C to TBO without removal of a cylinder or turbocharger.

At TBO, I took the airplane to Colemill for a Panther conversion with factory new TIO-540-J2B engines and four-blade Q-tip props. I called the conversion a transformation in Colemills advertising material and meant it. The short Navajo without nacelle lockers really benefits from the engine power increase and the Q-tip propellers yield a substantial 6 dbA interior noise reduction.

First hour fuel burn is 50 gallons with 40 to 42 GPH in cruise at 65 percent which on a standard day at 10,000 feet yields about 200 knots TAS with a takeoff weight of 6000 pounds. The airplane really likes to be between 14,000 and 16,000 feet which requires use of oxygen.

The insurance industry generally requires annual recurrency training at an approved facility and owner pilots can expect to pay a hefty price for the convenience and comfort of operating a Navajo. The premium for a $2 million combined single-limit policy with a $500,000 hull value was $14,500 with a requirement of annual recurrency training at an approved facility. The trip to Florida and tuition at FSI would add another $8000 for a tab of $220 an hour, assuming 100 hours a year.

I have attended both Flight Safety International in Lakeland, Florida and SimCom in Orlando. FSI is intense, comprehensive and expensive. The fidelity of the FSI Navajo simulator is much better than Simcoms, in my view, and the FSI ground school is clearly superior. Last year my FSI ground school instructor had over 3000 hours in Navajos. The year before, the Simcom ground instructor had none. A PA-31 owner/pilot needs to understand the systems of the airplane which in turn, requires a comprehensive well-structured ground school tailored specifically to the Navajo, not a generic multi-engine presentation.

Learning to use the autopilot is important of course, but George cannot be completely trusted. I have had two KFC-200 A/P hard-over failures, both in IMC. One was in pitch and the other in roll.

It gets your attention really fast as did the HSI gyro failure in IMC.The Navajo fuel system is simple and straightforward and allows a pilot to use all the fuel in the airplane with an engine shut down, which many other twins do not. PA-31 fuel gauges are notoriously inaccurate unless the tanks have been drained, new gauges which have been carefully checked, installed and the gauges themselves recalibrated.

The TIO-540-J2B and J2BD engines have been around for a long time and are reliable if, but only if, they are operated properly. These are stump puller motors generating over 700 ft./lbs. of torque, pulling 43 to 45 inches MP on takeoff, using 90 GPH. The injection and turbocharging systems are reliable and generally trouble free if you use clean fuel.

A squawk-free annual inspection by a shop specializing in Navajos can cost as little as $5000, but these airplanes are we’ll past voting age and a careful maintenance facility generally finds something to fix. Anyone with a Navajo already knows about Colemill Enterprises, and ought to know about Florida Aero in Lakeland and The Parts Network in California. All three are top notch outfits.

If you fly long distances with only a few passengers, a Nayak nacelle fuel tank installation should be considered. The tanks are aluminum, need not be kept full of fuel, hold 42 gallons, add only a few pounds to the empty weight and provide an extra hours range.

An accurate fuel computer such as Colemill installs with their Panther conversions is in my opinion mandatory if you fly long trips. Ten percent of all reported Navajo accidents/incidents involved fuel exhaustion, which with the inaccurate fuel gauges in these airplanes, is probably understandable.

Pneumatic pumps need be replaced at 400 hours, as do the engine mounts.Careful landing gear maintenance is important since the down locks are directly in line with the exhaust stream and accumulate carbon contamination in short order. The main gear needs to be cleaned and greased frequently.

The gear and flap speeds in the POH are maximum values, not recommended speeds. If you routinely use the maximum values, expect to be buying new gear doors, hinges and flap parts.

The inner gear doors on a Navajo are huge. If you keep the ball centered on retraction and extension, you’ll save yourself lots of money in repairs.The French Navy formerly used a fleet of Navajos for personnel transportation and found that if the pilots would tap the brakes before retracting the gear, the main landing gear bearings would last about 6 times as long.

Operating a Navajo is not cheap. The Part 135 charter services posting rates on the internet charge over $600 an hour (with a pilot) and some quote $2.50 or more per statute mile. Actual operating costs are obviously dependent upon the number of hours of utilization per year, but if you include fuel, maintenance, insurance, hangar, charts and engine and propeller reserves, you’ll find that the airplane costs over $700 per hour based upon 75 to 80 hours per year.

After nearly a half century of incident-free flying, perhaps I may be pardoned for having developed some definite opinions about airplanes and their care and feeding. The PA-31 Navajo is the best of the non-pressurized piston twins and about as much airplane as a non-professional single pilot/owner like me needs or probably should be flying. Mine has been a faithful steed for 22 years and it wont be for sale until my AME shakes his head and tells me to hang up my goggles.

Do I sound biased? Guilty as charged. Would I buy another one? You betcha.

Allan M. Bower

Sunriver, Oregon

I am the owner of Superior Airways, an air taxi charter business in Sioux Lookout, Ontario. We operate two Piper Chieftains and prior to Superior, I flew a Chieftain for several operators throughout northern Canada for over 1000 hours.

The aircraft are very reliable in the hands of a knowledgeable maintenance shop. There is much you can do to avoid common problems, but this entails spending money on overhauling components prior to their actual failure. The strongest point of a PA-31 is that they rarely, if ever, leave you completely stranded without many signs of impending problems. Mind you, you may be temporarily restricted to daylight VFR ops to ferry the thing home, but it almost always starts and gets back.

The first issue Ive had to deal with is the gear. Micro switches and both engine-driven hydraulic pumps must be replaced at their first signs of weakness. Raising the gear and waiting a longer than normal time for the gear lights to extinguish is your first clue. Intermittent gear horn warning beeps on the ground is another sign that a switch is starting to go. The power pack is also prone to failure after a certain amount of time.

The Lycoming IO-540s are strong, solid engines. Oil leaks are one persistent headache but are normally minor glitches. Ive flown these engines throughout the high Arctic at -40 degrees C and have never experienced a cylinder cracking. Its just important to keep high power on descent and to reduce power no more than 1-inch MP per minute in descent, while trying to keep them as warm as possible. Its also important in the cold temperatures to run the right oil and block off part of the oil cooler to keep the temps up. Pre-heating is essential before starting for long service life.

The biggest factor in obtaining long engine life is to run them often and change the oil every 50 hours. At a prior company, we accidentally ran a 540 on a 50/50 mix of jet-A and avgas for 10 minutes in the climb and the only damage during the tear down inspection was a cracked spark plug porcelain.

Overall maintenance is about getting ahead of the snags so that no maintenance is required in between inspections. We will be at that point about a year from now, but this involves changing out governors, hydraulic pumps, turbochargers, magnetos and so on.

Performance-wise, it is surprising how much TAS is related to takeoff weight. We run with the VG kit for a max takeoff weight of 7368 pounds. We see about 185 knot at 5500 pounds takeoff and 170 knots at gross. Fuel consumption runs at factory minimums of 30 GPH per side in the climb (giving about 1200 FPM at 130 knots) and can be reduced to 16 GPH a side in cruise.Oil consumption is minimal. Range with 182 gallons is about 800 NM with our second aircraft with the Nayak fuel tank option adding about another 200 NM.

The strengths of the aircraft are in the wide availability of aftermarket support and PMA spare parts available (usually). There are many operators with this type and therefore there is no shortage of experienced operators.They are an easy airplane to fly and will climb better than other light twins on one engine. The passengers also like them because of the bright, large windows, decent cabin size and fairly quiet ride.

We operate both aircraft with noise canceling headsets for the passengers to ensure the quietest ride possible.

The single biggest weakness of this aircraft is Piper. In my view, they are a company that has no clue about customer service, support, or how to even support a product. For this single reason, I would switch to Cessna or Beech for my next aircraft. You cannot call a Piper technician directly but must go through an authorized distributor, who must then relay your message and await a response in two to three days time. I cant even imagine Boeing telling an airline that a part is not available but could be manufactured but the wait time wont be known for another six weeks.

Our insurance for a new operator is 7.5 percent hull value, with a 10 percent rebate at year end for a clean record. This high premium is due to the complete lack of competition for aviation insurance in Canada so we simply pass this cost on to our customers. I believe a more common rate for experienced operators is in the 5 percent area.

Its a shame that Piper decided to abandon this line of aircraft size, as they do 90 percent of what a Beech King Air 90 will do, for far less money.Its certainly easy to fly and will haul a large family fairly quickly along with a load of gear into fairly short, unimproved strips. The downside is expect to pay about $300/hour for direct operating costs and reserves, along with up-front fixed costs such as insurance, training, charts, etc.

Mike Misurka

Via-mail

Also With This Article

“Piper Navajo Specs and Charts”

“Accident Scan: Pilot Competence”