Some insist it began production as the worlds largest, flying sweet potato and evolved into Snoopy crouching as he waited for his supper. The original PA-23, the Apache, seemed almost round and had such modest powerplants that single-engine operation could be hazardous … just like other twins with small engines. The last versions, the Aztec series, by contrast, are capable load-haulers with very good short-field performance.

The Apache is largely relegated to the training function for those looking for cheap-to-fly time builder but the Aztec remains one of general aviations stalwart twins and although it has high operating costs, it can be bought relatively cheaply.

Model History

In the early 1950s, the major aircraft manufacturers that had survived the post-war boom and thud scrambled to come up with a light twin. Beech and Aero Commander were first off the mark and Cessna was rumored to be coming out with one as well. Each was all-metal and of semi-monocoque construction. Until then, Piper had been a builder of steel tube-and-fabric machines but had acquired the Stinson Division of Consolidated Vultee. With it came the tube-and-fabric Twin Stinson, with 125-HP engines and twin tails. Piper installed 150-HP engines, changed to a single vertical fin and rather than redesigning the fuselage, simply covered the steel tubes with aluminum, creating the PA-23 Apache. It went on sale in 1954. Its fat, constant-chord wing allowed it to use the abundant short runways of the day but, with the chubby fuselage, kept cruise speeds leisurely.

The original Apache had five seats, Lycoming O-320-A1A engines of 150 HP each, swinging two-bladed props. Maximum gross weight was 3500 pounds (to put this in perspective, its only 100 pounds more than a V35 Bonanza and less than most of the big six-place singles), with a 1320-pound useful load. Top speed was 157 knots, with a published but optimistic cruise of 148 knots, while 135 to 140 knots proved to be more realistic. Average equipped retail price was $36,235.

Three years later Piper put 160-HP versions of the O-320 on the airplane and equipped it with full-feathering props. The primary benefit of the change was a 300-pound boost in gross weight. Other specs remained much the same, although single-engine performance actually suffered due to the higher allowable weight.

In 1960, Piper introduced the Aztec, a stretched PA-23 airframe with 250-HP Lycoming O-540-A1B5 engines and a larger tail with stabilator. Max gross weight was 4800 pounds. The Aztec was sold side-by-side with the Apache, and hurt the lighter airplanes sales badly. In 1959, 368 Apaches were built. In 1960, only 141 Apaches rolled off the line, compared with 363 Aztecs. In 1961 Apache production had fallen to 28 airplanes.

In a questionable attempt to resurrect sales of the Apache, Piper hung low-compression, 80-octane versions of the O-540 on the airplane in 1962, calling it the Apache 235. It hung on through 1965, with a total production run of 114.

Also in 1962, Piper added a longer nose to the Aztec, housing a baggage compartment. This airplane, the Aztec B, came with six seats, a pop-out emergency exit window and was available with optional fuel injection and AiResearch turbochargers.

In 1964, with the Aztec C, fuel injection became standard, and there was another boost in gross weight, to 5200 pounds. In 1966, the turbo option became a full-fledged model, with a standard oxygen system. During the run of the Aztec C, the engine TBO went from 1200 to 2000 hours, a benefit retrofittable to the older engines with the installation of half-inch exhaust valves.

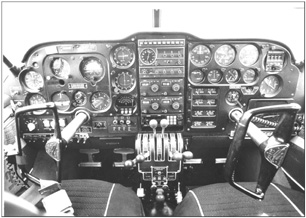

The D models had minor improvements, including a standard instrument arrangement. The E and F models have a nose extenstion with a fiberglass cap. The longer, pointed nose is a detriment from the radar standpoint, according to Aztec expert Tom Baum. The more tapered nose allows only a 10-inch radar antenna, not a 12-inch.

The big changes in the PA-23 all happened in the early 1960s. After the Aztec C, the alterations were mostly refinements. During the 26-year history of the PA-23, 2036 small-engined Apaches were manufactured, 114 Apache 235s and approximately 5500 Aztecs.

Market Scan

The PA-23 should be thought of as two different airplanes-the Apache and the Aztec. With such a variety of power, weight and age, a buyer can find a PA-23 to fit almost any budget. Original Apaches in average condition carry price tags around $30,000 and its not hard to find one for much less.

Its likely, however, that a PA-23, either Apache or Aztec, bearing a used-car price tag has had quite a tough life, including use as a multi trainer or cargo-hauler and eventually retiring into neglect and disuse. The irresistibly low prices on some of these airplanes could be siren songs and due to the complexity of the systems, keeping one of the neglected birds airworthy has proven to be expensive to more than one buyer seduced by the low price. Twins arent cheap to operate and the PA-23 is no exception.Figure about $225 per hour, wet, to run a normally-aspirated Aztec, based on 150 hours a year.

On the other hand, there are Apaches and Aztecs that have been flown regularly and kept in great shape and although not exactly steals, they can be purchased for the price of a late-model, four-place single. Prices on Aztecs are generally much lower than those on other light twins, such as Beech Barons and Cessna 310s. Owners assert that their Pipers may not be as pretty, quick or fuel-efficient as other light twins, but they are generally easier to fly, reliable and better at hauling heavy loads and operating out of short fields. We have consistently been informed that a good experience in owning an Apache or Aztec depends on having a thorough pre-purchase inspection and good initial and recurrent training.

Accommodations

The fifth seat in Apaches and early Aztecs is relegated to the back of the cabin, where it takes up a lot of space in the 200-pound capacity baggage compartment. A few Apache owners even remove the seat from the airplane, as it is virtually unusable and is just excess weight. Beginning with the B-model Aztec, there are three full rows of seats and 150-pound capacity baggage compartments fore and aft.

The PA-23 cabin is spacious and comfortable, with plenty of elbow, head and leg room. The airplanes can haul a respectable load, although they cant, as some owners would suggest, fly with anything you can close the doors on.Still, even well-equipped Apaches and Aztecs can carry full fuel, four or five adults and baggage, despite zero-fuel-weight restrictions imposed by an Airworthiness Directive (83-22-01) that was issued to prevent damage to wing-attach fittings.

The Apache 235 and the original Aztec have zero-fuel-weight limits of 4000 pounds. In naturally aspirated B through F models, any load above 4400 pounds must be fuel. The limit in turbo models is 4500 pounds. We have found that a surprising number of owners are not aware of the limitation, so wing attach fittings should be a checklist item on a pre-buy inspection. While there, check for corrosion in the tubes in the bottom of the fuselage.

Systems

All Apache 150s and 160s have one 36-gallon fuel bladder in each wing and many have an 18-gallon aux tank on each side, too. Apache 235s and Aztecs have two 36-gallon cells in each wing. The F model, as mentioned earlier, could also be fitted with 20-gallon internal tip tanks. As fuel bladders age, owners report a frustrating frequency of leaks, so periodic inspection and replacement has to be included in the budget.

Also on the Aztec Fs options list was an auxiliary hydraulic pump on the right engine. Earlier models came with only one pump on the left engine to operate landing gear and flaps. If the left engine goes kaput, there’s a hand-pump underneath the control console that requires 30 to 50 strokes to get the gear up or down, a significant challenge during a real emergency. There’s also a CO2 bottle to blow the gear down if the emergency pump doesnt work.

The gear and flaps are hydraulic, meaning that the aging system will provide the owner with the joy of tracing leaks on a regular basis. One owner reported that he replaced some valves, hoses and fittings every year so that everything was changed over five to six years. To check the level of the hydraulic fluid, the airplane must be up on jacks with the gear retracted and flaps extended. Otherwise, adding fluid overfills the system, leading to a very red airplane when the gear is retracted after takeoff. Many, but not all, Apaches have been upgraded with dual alternators and vacuum pumps; avoid those that have not.

Reports of adequacy of cabin heat vary, with one owner stating that his passengers had to wrap up in sleeping bags to stay warm during winter flights. That airplane turned out to have crushed heat ductwork requiring many hours of labor to fix and even then, the result was not adequate, despite also plugging the many leaks in the aft cabin bulkhead. (Airflow in the fuselage is from the tailcone forward.) Some models of the gas-fired heater have maximum hours between overhaul limits, so a Hobbs meter on the heater is a good investment.

Performance, Handling

The fat, high-lift airfoil has a lot to do with the PA-23s docility and good low-speed performance, but it costs more than a few knots in speed. Owners of 150- and 160-HP Apaches report 135 to 145 knots on 16 GPH at 75 percent power. The big-engined Apache is faster but is a glutton for avgas. Figure on about 160 knots on 29 GPH at high cruise for the Apache 235. Early Aztecs claim 178 to 182 knots while burning about 26 to 28 GPH at 75 percent, more realistic cruise is 160 to 165 knots. The E and F models are a few knots slower on the same fuel. Up high, around 24,000 feet, a Turbo Aztec can sizzle along at 190 to 200 knots with fuel gushing at 30 to 35 GPH.

As mentioned earlier, the airplanes are exemplary short-fielders. The Apache models need less than 1100 feet to get in or out over a 50-foot obstacle, although the published Vx is very near Vmc. Early Aztecs require less than 1250 feet. Newer, heavier Aztecs use up a bit more real estate, but not much: Figure on about 2000 feet to leave and less than 1600 feet to arrive over a 50-foot obstacle in an E or F model.

Single-engine performance is on par with other light twins; that is, its pathetic. Published single-engine rates of climb vary from 180 FPM for the Apache 160 to 240 FPM for the Apache 150 and naturally aspirated Aztecs.

The Apache 235 and Turbo Aztecs climb at about 220 FPM on one mill. However, some Apache owners have told us theyd consider themselves lucky to hold altitude at gross weight with only one fan turning and we saw barely 100 FPM while getting single-engine practice in a lightly loaded Apache 160 on a warm day. We saw little better during a workout in a Seneca III under a hot Florida sun.

In our opinion, the edge of the single-engine performance envelope on light-light twins-those with normally aspirated engines of less than 200 HP-is really too close to being unsafe for comfort. There simply isn’t enough horsepower available to produce anything but a barely flyable airplane. A positive rate of climb depends on perfect technique and on top of these demands, the pilot is presented with the specter of engine-out handling difficulties, such as the tendency to roll over towards the dead engine.

In this respect, the Apache is no worse than more modern designs. For example, Pipers own PA-44 Seminole, a late-1970s design, has 180-HP engines and a useful load of about 1400 pounds. The original Apache, with 150-HP engines and a useful load of 1320 pounds, has a higher single-engine ceiling (5300 feet versus 3800 feet), higher service ceiling (17,000 feet against 15,000 feet) and better single-engine rate of climb (240 FPM versus 212).Proper recurrent training is the best protection against these shortcomings. It also helps to fly as much below gross weight as possible, and to install vortex generators.

In the air, with everything working properly, the twins feel like big Cherokees, but with more responsive controls. However, the ailerons are somewhat heavier than the rudder and stabilator (elevator in early Apaches).One idiosyncrasy that will present itself to the transitioning pilot is the tendency of pre-1976 models to pitch up strenuously when flaps are lowered.In 1966, Piper published a service letter (No. 474) suggesting the deployment of small amounts of flap, rather than stabilator trim, to counter nose-heaviness in the pattern; it works. The manual pitch trim control, by the way, is a large crank on the ceiling with a smaller crank (a knob in later models) inside it for yaw trim; both are very sensitive. Another idiosyncrasy is the location of the gear lever on the right and the flap lever on the left of the center pedestal. Pilots do get these mixed up and the latch thats supposed to prevent inadvertent gear retraction doesnt always work.

The ability of the bulbous airplanes to bleed off speed rapidly comes in handy when its time to get into landing configuration. Maximum speeds for lowering gear and flaps in Apaches built before 1960 are a ridiculously low 109 and 87 knots, respectively.

Limiting speeds in later models are a more manageable 130 and 109 knots. Also, in 1965, Piper came out with a modification kit for Aztecs and Apache 235s allowing quarter-flap deployment at 139 knots and half flaps at 122 knots.

Pre-1971 Aztecs tend to thwart the pilots best attempts at trimming and roam a bit in altitude. A stronger stabilator down spring in the E-model improves longitudinal stability, but control pressure in the flare suffers as a result. The stabilator and stabilator-balance system were changed with the introduction of the F model, but Piper later switched again from external to internal balance weights after AD 79-26-1 targeted cracks and attachment problems. Another change in the F model was incorporation of a flap-stabilator interconnect to reduce the pitch-up tendency.

Maintenance, Parts

Reports of parts availability are mixed. Some say certain parts are becoming difficult to find, while others told us everything is readily available from New Piper, PA-23 specialty shops and salvage yards. Owners also tend to be very picky about who maintains their airplanes. Indeed, many owners do much of their own work under the supervision of IAs. You can spend a fortune having a mechanic learn your systems, one owner said.

Several ADs require repetitive inspections and work and some are quite expensive. In our check of ADs for the PA-23, we found 102 listed. The most recent, 2005-01-10, applies to turbocharged Aztecs and requires replacement of the turbocharger oil tank and work on the fire shroud to prevent an in-flight fire.

Among the others on the list are: AD 63-12-2, on elevator butt ribs and doubler plates; 63-26-3, elevator and rudder castings; 72-21-1, control pedestal support bracket; 74-10-1, flap hinges; 78-2-3, stabilator tip tubes and weights (on Aztec F); 78-8-3, rudder hinge brackets (Apache 150 and 160); 79-26-1, stabilators (most F models); 80-18-10, fuel selector valves and cables; 80-26-4, cabin entrance step support frame structure; 81-4-5, flap controls and hinges; 85-14-10, Hartzell blade clamps; and 88-21-7, fuel lines, caps and filler compartment covers. In many cases, the repetitive inspections are no longer necessary after affected parts are replaced or modified.

Modifications, Support

Sierra Industries offers STOL kits for the PA-23, Met-Co-Aire offers tip tanks that increase fuel capacity by 48 gallons as we’ll as new wing tips, turbochargers can be had from Rajay and vortex generators from MicroAerodynamics (www.microaero.com).

Considering the number of Aztecs built, its curious that there is no organization devoted to their owners. The Flying Apache Association caters to Apache owners primarily but includes owners of all versions of the PA-23 among its membership. They can be reached at 561-499-1115.

Owner Feedback

My family corporation has owned a 1971 Turbo Aztec E since 1982. During that time, the aircraft has proven to be solid, dependable and comfortable. Full fuel payload is 1027 pounds, which provides plenty of options for almost any mission. Typical true airspeeds at 65 percent power range from 170 knots at 6500 feet to 187 knots at 12,500 feet, all while burning 27 GPH. If necessary, onboard oxygen for each seat allows more speed in the mid-teens, up to 202 knots TAS at 17,500 feet using the same power and fuel flows.

The aircraft has been updated with avionics a couple of times over the last 20 years and four years ago I had both engines overhauled by Western Skyways using Millennium cylinders, GAMIjectors and overhauled or replaced accessories, turbos and hoses.

Because of the age of the airframe and the increase in fuel costs, I had recently considered moving to a high-performance single. What I found is that there are very few general aviation aircraft, singles or twins, that can provide the same mission flexibility as economically as our Turbo Aztec. The turbos allow me to climb out of the heat and bumps in the summer, fly with confidence into most high-altitude airports and carry six souls and reasonable baggage in comfort and speed into the biggest or smallest airports in the country.

There is no question that the oper ating costs of an A-36, Centurion or Saratoga are lower than the Aztecs. However, the higher cost of those airframes will negate some of that and none of the high-performance singles have the back-up systems of this durable twin.

Despite having more than 800 hours in the aircraft, I have not had time to complete an instrument rating, so insurance runs $5500 annually for a hull value of $150,000. My insurance broker urges me to get instrument rated every year by telling me I could save close to $2000 in insurance costs.

The engines are bulletproof and made it to 2200 hours before I decided to overhaul them in the spring of 2000. Although I do not run the engines lean of peak, they are running smooth and cool and I expect to make it to TBO within the next 10 years.

With all this in mind, I decided to continue the upgrades to the aircraft and make an effort to complete my instrument rating in 2005. When I am finished, I believe our humble Turbo Aztec will be as comfortable and capable as any six-place general aviation aircraft manufactured within the last 10 years, at a small fraction of the cost.

John Settle

Via e-mail

I grew up in an aviation family with my father and grandfather in the FBO business. My father was a lover of the Cessna 310 series, owning three different models for our personal transportation over as many decades. So, naturally when it came time for me to buy my own light twin, I bought an Aztec!

I am an Army aviator and the airplane had to meet specific requirements to justify a twin. To split fuel costs, I needed to carry six people and baggage comfortably. I needed all weather capabilities-radar and known-ice-to insure we could travel over holiday weekends. I needed the range to cover 500 miles. I needed low initial costs with manageable operating costs. Only the Aztec could meet my needs.

For $70,000, I found a 1967 C-model built in 1968. It has 2035 pounds of useful load, known-ice, weather radar and an IFR-certified GPS. I bought the airplane in 1998 with about 4000 hours on the airframe and under 500 hours on the engines. Over the past six years, I have put about 700 hours on the airplane. My only surprises have been insurance and an early engine overhaul.

I hold an ATP/MEL and at the time of purchase had around 5000 hours, but only about 200 hours MEL. My insurance cost was a staggering $1200 for $70,000 hull and $1 million liability. (Actually, for six years ago, thats a low price. Ed.) I was assured that as my time in type grew, this cost would come down. This year, I have over 7000 hours and nearly 1000 MEL. My insurance cost this year is $2400 or double what it was (Realistic from what we have seen-Ed.).

My other costs are as follows: Overhauled power pack: $1500. Overhauled one engine with my used cylinders: $12,000. Met applicable ADs: $2000. Overhauled fuel servo: $1200. Overhauled props: $8000. My annuals run about $1500, plus parts.

I run full throttle and about 2350 RPM at 75 degrees rich of peak. This gives me 165 knots on 27 GPH. The airplane holds 140 gallons of fuel, giving me better than five hours worth of gas and still leaving nearly 200 pounds per seat for passengers and baggage. The front and rear baggage compartments hold 150 pounds each and provide a very large area to put everything in and to control the CG.

I believe that Mr. Pipers philosophy was to build airplanes as inexpensively as possible. As a result, the Aztec is built simple and rugged. I am sure cost drove many of the design decisions, such as the wing airfoil and stabilator.

The Aztec is far from the prettiest and fastest machine out there, but Pipers low-cost decisions are the reason why guys like me can afford a twin.

Howard Swan

Springfield, Virginia

N80FF is a 1972, E-Model Aztec owned by Dr. Howard J. Brud Ludington. Modifications include a new interior, a new paint job specifically designed to reduce the prominence of the infamous Aztec snout, as we’ll as an engine and propeller overhaul.

Several airframe modifications from Diamond Air were installed, including a single-piece windshield, an extension to the dorsal fin and vortex generators. Finally, tinted windows with sound-proofing were added to the rear windows. All of the work was done (incredibly well) by Todd May and crew at Oxford Aviation in Oxford, Maine. We were pleased by their outstanding customer service.

The aircraft still flies like an Aztec. The main differences include about 7 extra knots in cruise. TAS at 8000 feet is about 167 knots at 70 percent power and a significantly reduced Vmc. Landing is a bit different, as the airplane is slippery and has a reduced stall speed, but the extra rudder authority is very nice. All in all, we couldnt be more pleased.

Rob Montgomery

Via e-mail

I own a 1964 non-turbo C-model with just under 5000 hours and 1880 SMOH RE and 1645 SMOH LE. Ive owned it since 1999 and have flown it for a total of 338 hours. I paid $56,000 for it and it is worth between $45,000 and $50,000 now. My insurance ($75,000 hull $1 million/$100,000 liability), runs about $3200 per year. That cost has not changed much over the five years Ive owned the airplane.

Annuals run about $2500 with a few minor repairs, although the first annual was over $22,000. Adding up all Ive spent produces a figure of $153.28 per hour dry, based on the 338 hours Ive flown it. I plan my trips for 160 knots and a fuel burn of 25 GPH. The book says a C-model should go faster than this, but I never see it. Back when fuel in central Texas was less than $2 per gallon, I used the figure of $200 per hour wet as my figure for Aztec versus airline ticket decisions. Now I use $225.

I keep thinking that Im about to round the corner on the maintenance, but so far this has not happened. Although it is maintenance-intensive and thus expensive, it is fun to fly when its working. It hauls a ton-literally. The useful load on mine is almost 2100 pounds and its roomy and comfortable to travel in. The two baggage compartments are nice and Ive never had a problem with insufficient baggage space.

Its single-engine performance is OK when lightly loaded, but Id hate to lose an engine on takeoff at gross weight on a typical summer day in Texas.Every light twin pilot should do a few what-if accelerate-go calculations to see the distance needed climb to 50 or 100 feet AGL after losing an engine.

The Aztec makes a good instrument platform. It is easy to fly and has no bad habits. The early models had only a single hydraulic pump on the left engine, which is also the critical engine. The flaps are hydraulic and move fast when the gear is not moving. When selecting both gear and flaps, the gear has priority.

The nose pitches up strongly when the flaps are used, making one reach for the overhead trim. The overhead trim takes a little getting used to, and is constantly turned the wrong way if you move back and forth and fly it from both the left and right seats. It is a job to wash and wax because its a big airplane. It is also heavy and requires a tug to move it on the ground, unless you are on a level, hard surface. On grass, Ive never been able to budge it by myself, but with two or three other people, it can be moved.

New and used parts have been readily available. Matthews Aviation is a salvage yard that specializes in Aztecs. You can get most anything from there.

Ronnie Hughes

Austin, Texas

Also With This Article

“Piper Aztec Charts”

“Accident Scan: Fuel-Related Wrecks”