There’s a reason why Mooney’s entry-level speedster has such a loyal following. And you don’t have to be a loyalist to appreciate the 201/M20J’s high points. It has a familiar Lycoming IO-360 engine mated to a sleek airframe that has timeless good looks and ramp appeal Plus, you buy a Mooney for speed, and for the 201, the bottom line is 155 knots on roughly 10 GPH. As a bonus you’re treated to sports car-like handling that makes it a good IFR traveler, even if you don’t fill all four seats.

The M20J had a long production run in the company’s rocky history, and the last 201 came off the line in 1999 as the Allegro. But there are plenty of 201s to choose from on the used market in various conditions. Make no mistake—you’ll want to choose one carefully. Neglected ones can be a nightmare when they hit the maintenance floor. As for support, we’ll set the record straight and say up front that despite the company’s recent shutdowns, getting parts and general factory support seems to be a non-issue.

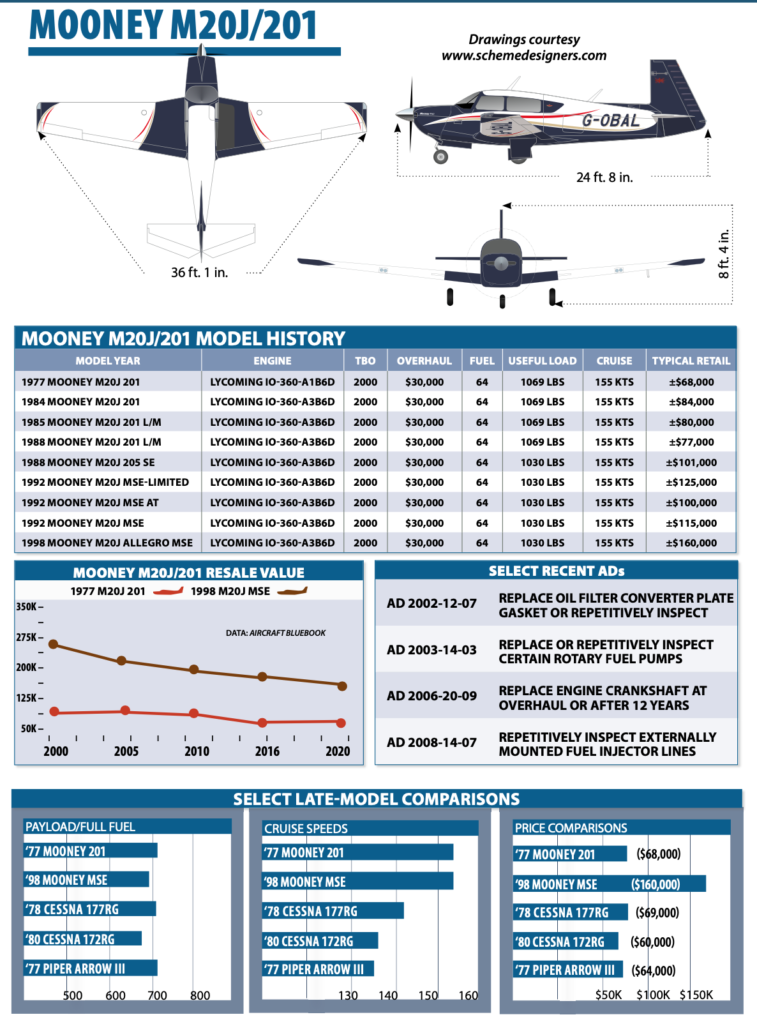

MODEL HISTORY

Eyeball the Mooney line and you’ll see the airframes all share the same basic styling. The Mooney airframe has evolved over the years, but the concept of a semi-monocoque rear fuselage mated to a metal-skinned steel-tube cabin, a long and slender tapered wing and distinctive reverse tail has endured, and is mostly responsible for the entry-level 201’s speed and efficiency.

The J-model Mooney evolved most directly from the F model, which was itself descended from the short-body C models of the mid-1970s. The first J model or 201—the number derives from its supposed top cruising speed in MPH—appeared in 1977. To be fair, it should really be more like a Mooney 184, since this model doesn’t honestly cruise at 175 knots. The old Mooney naming conventions—Executive, Chaparral, Statesman—were ultimately nixed in favor of the top-speed moniker.

For some creative marketing, Mooney even went so far as to reserve as many 201 registration numbers as possible for the new airplanes. It sported a 200-HP Lycoming four-banger—the IO-360—improved landing gear and a sloping windshield, among other changes. All of these were the product of a concerted effort by Mooney to kick the model line up a couple of notches.

The 201 is, to the surprise of many, very much the work of the late LeRoy LoPresti. LoPresti had a long aeronautical background, including a stint on the Apollo lunar program at Grumman. He became a near legend for his ability to get the utmost from an airplane through aerodynamic cleanups, which he’d done with success on the Grumman Tiger.

Applying his magic to the M20F model, LoPresti and the Mooney team created the M20J. A number of changes were made, the most visible being a new cowling and a more aerodynamic windshield. The interior was addressed, too, with adjustable seats and a contemporary flat panel with organized electricals and circuit breakers rather than the typical dog’s breakfast arrangement of the 1960s and 1970s. But that doesn’t mean avionics shops enjoy working on them. It’s an unspoken (and sometimes spoken) rule that when quoting an avionics package, you add the “Mooney factor” to the bottom line, partly because the radio racks are riveted in place. Plus the electronics are packed in like sardines.

PRODUCTION AND PRICING

Even though Mooney sold over 1000 M20Js in the first few years, by 1985 the general aviation slump was taking its toll so Mooney transformed the J into the 201 LM (for “Lean Machine”), a stripped-down version with basic IFR avionics for a bargain price. Two years later, the M20J got some more tweaks (gear doors) and was renamed the 205. Inexplicably, the 201 was still being produced, as was the 201 LM, and oddly, Mooney was selling three airplanes that were more or less the same: all M20Js, but with different equipment. In 1988, the 201 was dropped and the 205 became the 205SE. It’s tough to keep straight.

And a year later, Mooney realized it was simply confusing customers and returned to the 201 name. That same year a trainer version was introduced, called the AT. It was intended only for flight schools and is notable for the inclusion of speedbrakes. The new ones we flew at a busy aviation university had minimal avionics—rare for the model that’s usually loaded. In fact, we remember that it didn’t even have an autopilot and sadly, a student and instructor perished after losing control at night. To this day we wonder if an autopilot would have changed the outcome.

In 1991, Mooney abandoned numerical names and re-dubbed the 201 the MSE. There was a version with special equipment in 1992 called the MSE Limited. In 1993, all special variants were dropped and just before it abandoned the J model, Mooney gave it one more name: the Allegro, ostensibly to go along with the Ovation and the Encore, the redo of the 252 that was also dropped just after it reappeared. Very few Allegros were made, but they’re arguably the most luxurious of the 201 litter.

Total production of the M20J—regardless of name—totaled about 2150 with about 1600 registered in the U.S. The airplane retains a loyal following and the fact that demand for it remains strong is evidenced by price trends: The 201’s base price more than doubled in the first six years, from $46,725 (1979 base) to $97,500 (1985). On the used market, the 201 continues to be a strong seller.

We hit the Summer 2020 Aircraft Bluebook and found that resale values are reasonably good. A 1986 M20J has an average retail of $90,000, while a 1979 is average priced at $70,000. A good one will sell quickly, even against lower-priced hangar queens and especially against ones that are neglected. As one would expect, corrosion is the enemy.

For comparison, a 1986 M20K with its 210-HP turbocharged Continental TSIO-360 has a suggested retail price of $119,000, according to the Aircraft Bluebook.

MODEL-YEAR TWEEKS

The biggest operational shortcoming of the original M20J was its low gear-operating speed (Vlo) of 107 knots for both retraction and extension. This, together with the low flap extension speed (Vfe of 114 knots), caused pilots grief in high-density areas and led to the airplane’s reputation as a hot-handling, hard-to-land performance machine, which it really is not, although we were dumbfounded while researching the latest NTSB wreck reports for the airplane. It’s littered with landings—and go-arounds—gone wild, evident that Mooney pilots still struggle with landing these airplanes as they always have.

Mooney has tried to help, at least in dirtying the airplane up at higher speeds. Vle (gear extended speed) and Vlo/e (maximum gear operating/extend speed) were increased to 132 knots for the 1978 model year. The 107 knots maximum retraction speed remains. Even these speeds are low, given the slickness of the airframe. Speedbrakes were offered as a factory option in 1986 and aren’t a bad feature to have; you can retrofit the Precise Flight boards to any model and we think for many the investment is worth it.

Where the first 201s have throttle quadrants with a pistol power lever, carried over from the C model, in 1978 this was changed to conventional push-pull engine controls. The panel and central console/pedestal were redesigned twice. In 1980 (1981 model year), the panel and glareshield were changed to the same configuration as that in the 231, with the extended section over the radio stack to provide more room.

Some Mooneys can be vibey, and this change also is credited with solving vibration and rattling that had been an annoying problem in earlier 201s. For all its reliability, the IO-360 isn’t the smoothest engine out there. If you’re doing an engine swap, we say change the mounts, too. The ventilation system also was improved and the shaped wingtips with faired navigation and strobe lights that were first introduced on the 231 were added.

Further aerodynamic and several serviceability changes were made for the 1984 model year. The nosegear doors were redesigned to make them close fully on retraction, a fairing was added to the tail cone and a one-piece belly fairing was installed. This is a desirable feature; otherwise maintenance access to the belly is a hassle. The single fairing, which is fastened with 38 Dzus fasteners, replaces eight separate access panels with 175 screws. Access to the engine bay was improved, too.

Over the years, empty weight increased by roughly 80 pounds; basic empty weight was 1640 pounds in 1981, 1671 pounds in 1984 and 1726 pounds in 1992. Some versions have more than 200 pounds in optional equipment and end up with full-fuel payloads around 460 to 470 pounds. In any case, don’t plan on much more than 600 pounds with the tanks full.

The big changes in the Model 205 were in the electrical system and landing gear. The 205 electrical system is 28 volts compared to the 14-volt system in earlier M20Js. The higher-capacity system is an improvement even though the 70-amp maximum output of the alternator is unchanged, because it can produce 70 amps whereas the earlier system is capped out at roughly 60 amps. Keep that in mind if you plan to pull the vacuum system in favor of an all-electric avionics suite. Bigger is better.

Battery rating also increased. Along with that, Mooney added an improved electric load monitoring system to supplement the high- and low-voltage annunciators—idiot lights that don’t help manage demand to any great extent. Of course these days digital engine monitors and primary engine displays have lots of electrical system health monitoring.

The 205 gear system incorporates the M20K doors that fully enclose the gear when retracted and is the major contributor to the modest claimed speed increase of 4 MPH. The mechanical, three-position cowl flaps were replaced by an electrically operated, infinitely adjustable system. Some pilots like the manual flaps better, but they need to be kept in adjustment. Rigging is important in any airplane, and if you want to chi chi the best speed it’s worth the expense to have a good shop rig the airplane by the book.

Gear speeds were raised to a Vlo/extend of 140 knots and Vle of 165. A flap preselect system was offered for the first time and Vfe/approach (15 degrees) was raised to 132 knots. The higher speeds were lost when the 201 returned in 1989.

HANDLING

Pilots new to the 201 are surprised that control pressures are higher than in other airplanes of similar size and power, thanks to the push-pull tubes rather than cable-actuated flight controls. The result is direct, fast and linear response. The stiff roll feel is due to the tubes bearing against rub blocks that help carry the aerodynamic loads without binding. Autopilots are an asset on long trips.

Rudder is the lightest control in the three axes, but it also is the least powerful, although there’s plenty of rudder to handle crosswinds. We’ve landed 201s—sitting straight up in the seat—with 20 knots across the runway, with control authority to spare. Pitch changes with configuration and power changes are significant. A go-around or missed approach with full flaps requires anticipation and generous use of trim, so be ready for it. And be ready to stuff the nose down without delay should the engine quit in initial climb.

In landing configuration, application of power results in a strong pitch up. One trick of note is that the flap and trim motors run at the same speed, which means that the pitch change with flap extension can be nicely balanced by running the trim in the opposite direction at the same time.

Stalls in a well-rigged 201 with the stall strips properly located on the leading edge are brisk but not tricky. There can be a pronounced wing drop as the nose falls through, as it usually will. The airplane isn’t approved for spins and they should be avoided. They’re recoverable by conventional means but may require more altitude than the pilot is willing to give up or has available. Again, stay in the bubble during initial climb, and watch the speed with flaps and gear hanging out on approaches.

Mooneys have long had a reputation as floaters on landing. And they will float, if flown too fast on final, which most pilots tend to do. Nail the speed, however, and you can plant the airplane right where you want it, with minimum runway used. Touch down too fast and force the airplane on, and you’ll be in for a wild wheelbarrowing or skidding ride that could end in a prop strike or damaged gear. Similarly, takeoffs can be sporting and bouncy, too. The trick during takeoff is to set the trim properly, use flaps as recommended and apply a little back pressure. When the airplane wants to fly, don’t try to hold it on the ground. Let it come off.

The biggest handling challenge occurs not in the air but on the ground. The turning radius is fairly large. This, coupled with the long wingspan and low seating position, creates taxiing and ground maneuvering problems for transitioning pilots. The limited nosewheel turning radius also creates maintenance problems. Untrained or careless line workers towing Mooneys (and plenty of other models) are known to exceed the limits and damage steering horns, trusses and other nosegear components.

REAL SPEEDS, DWELLING

At 60 to 65 percent, true airspeeds average 150 to 155 knots and endurance with reserves is 4.5 hours or better. Some owners report 160- to 165-knot airspeeds and, while some airplanes definitely are faster than others, we’re skeptical of these claims. Plan on 150 to 155 knots on about 10 GPH.

Be careful with the loading. Typically equipped 201s can haul three 170-pounders plus about 40 pounds of baggage. With partial fuel loads—say 50 gallons—the Mooney still offers good range with seats filled. The 201 has outstanding altitude performance for a low-power, normally aspirated single, thanks to its comparatively high aspect ratio and efficient wing. Its performance is good enough to make cruising at 14,000 to 15,000 feet a practical matter, with oxygen of course. Service ceiling is 18,600 to 18,800 feet, depending on the version and if light, a 201 can go there, so bring your oxygen.

The J model isn’t a rough-field airplane, although it will handle short runways admirably well. The low-hanging gear doors almost brush the ground and the prop has less than 10 inches of clearance. Well-manicured turf runways are no problem; rutted gravel will beat the heck out of the doors, as will muddy surfaces.

Mooney cabins in general have a reputation for being cramped, but are in fact nearly as wide as a Bonanza. But it’s the shape of the cabin section that makes them feel snug. The small frontal area of the airplane means that the seating position is rather sports car-like, with feet stretched out in front. This is in contrast to, say, a typical Cessna, which is more like sitting in a kitchen chair. There is definitely lots of legroom: Pilots shorter than 5 feet 9 or so may have to use a booster cushion to reach the pedals. For folks with bad backs, the Mooney can be an irritant and it’s not easy to ingress and egress gracefully. We know pilots who sold their 201s because of it.

The M20J is relatively noisy and some planes are worse than others. Vibration results in cracked cowls, baffling and cowl flaps. Noise-canceling headsets, a good audio system, a thicker windshield and sound insulation help with the noise. So does prop balancing.

The baggage bay is of adequate size and is approved for up to 120 pounds. Most owners don’t mind the location of the hatch, which requires you to lift baggage over the sill rather than place it in. The baggage door doubles as an emergency exit for rear seat passengers (although some owners say it’s too small or too hard to reach). The earlier models have fixed rear seatbacks, which occasionally causes loading problems for really bulky items. The baggage door isn’t all that large so loading in snowboards and golf clubs into the airplane isn’t easy. There are mods for fold-down rear seats to address this. Some owners yank the rear seats altogether.

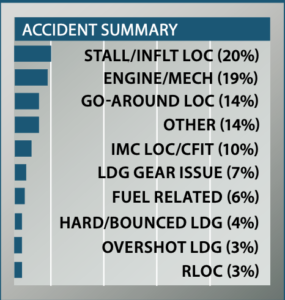

After reviewing the 100 most recent Mooney M20J accidents we were pleased to observe a very low rate of fuel-related engine stoppages—six. Only one pilot ran a tank dry and then didn’t select the other. One pilot did use up all of the fuel in the airplane before arriving at an airport—a rate we’ll below what we expect to see. Both results speak we’ll of the Mooney fuel system.

The other four fuel-related stoppages were from water in the fuel (well, ice in one of them). It appears that the water may have gotten into the tanks due to rain. That’s usually a fuel cap issue. We advise checking the fuel caps to see if there’s a possibility that they will admit rainwater and—no matter what—check the tanks for water before flight.

There were 19 engine stoppages for mechanical reasons, usually poor or unperformed maintenance. However, six of the stoppages could not be explained.

We wondered about the pilot who was “maneuvering at about 1000 feet” when he said the engine quit. He lined up to land on a street. The engine came back to life. The pilot pulled up, hit power lines and then was confident enough in the powerplant to avoid nearby airports for a precautionary landing. He flew 150 miles back to home plate where he discovered serious damage to the airframe.

At 20, the number of VFR inflight loss of control events, almost all of which were stalls, waved a big red flag. Most were on takeoff or go-around as pilots tried to get performance out of the airplane that had never been built in. One pilot tried an intersection takeoff (sigh, so many accident reports start with that comment) and stalled trying to get over trees at the end of the runway.

What got our undivided attention was landing-related accidents. Only three pilots lost control while rolling on the runway (we think the M20J has excellent ground handling) and three ran off the end of the runway. By itself, that’s not bad. However, the accident reports revealed to us that, in our opinion, there has been an ongoing competition among M20J pilots of which we were not previously aware.

We’re calling it the “Let’s-see-who-can-fly-fastest-on-final-and-use-the-airplane-again-after-landing” (LSWCFFOFAUTAAAL). Mooneys are clean machines, and pilots seem to have a hard time slowing them to 1.3 Vso on approach, but are determined to force them onto the ground. That rarely goes well. One pilot was so determined to land that he hit the prop on the runway.

One LSWCFFOFAUTAAAL pilot tried to turn his airplane sideways to get stopped but as the airplane crested a hump in the runway it was still going so fast that it became airborne and ended up in the trees off the end.

Not surprisingly, the LSWCFFOFAUTAAAL competition resulted in lots of go-arounds—and lots of crashes on those go-arounds—14 from loss of control plus a half-dozen stalls.

In our opinion, the accident chain in fully a quarter of M20J accidents started with too much speed on final. We strongly suggest that the LSWCFFOFAUTAAAL competition be ended now and the results announced. We don’t have a winner, yet, but we know who lost: the airplanes and their occupants.

UPKEEP

Like most aging airplanes, corrosion is a concern and fuel tank leaks are common on aging Mooneys. Repairs are expensive and some owners have chronic problems. Others have none, depending on storage. Reseal quotes can run north of $12,000 if the tanks need major work involving hand scraping the old sealant through hard-to-access fuel bays. It’s not a fun job.

Another recurring fuel system problem is water contamination caused by faulty fuel cap seals and/or corroded fillers. Avoid it and change the cap O-rings at annual.

Leaking water also is responsible for another expensive problem. Poorly sealed (or deteriorated sealant in) windows or leaking storm windows allow water to seep into insulation, which leads to corrosion of the tubular cabin structure on the pilot’s side. We’re told that 50 percent of all 201s have the problem to some degree and early (through 1982) Mooneys are the most affected. Keep this in mind when doing a purchase eval.

Inspection and repair is expensive because the interior and insulation have to be removed. Even if an airplane has been repaired, replacing tubes is frequently required and the problem can recur if an improved type of insulation was not installed or if window leaks recur.

We suggest a detailed inspection of all flight control elements, especially if an airplane has been repainted. Paint stripper can penetrate and corrode torque tubes, bell cranks and other elements of the system. Exhaust system elements, especially flame tubes and mufflers, also are repeat maintenance items, in part due to poor quality, according to some maintenance technicians.

The ram air system also is prone to failure and regular inspection for deteriorating gaskets and proper operation is suggested. Some owners recommend sealing it and forgetting it. Using it adds a barely discernible bump in MAP. Finally, the next best things to a warm, bird-free hangar are cockpit covers and cowl plugs. Birds like to nest in the tail cone and plugs in gaps will help. They don’t seem to like the nose openings as much as in Cessnas or Pipers.

One of the best things you can do to help support a 201 and any Mooney is join the Mooney Aircraft Pilots Association, or MAPA (www.mooneypilots.org), which has a magazine and an active forum. There’s also the Mooney Flyer (www.themooneyflyer.com), the official online Mooney magazine. These resources can help you find lots of mods and shops that specialize in Mooneys. Some mods are intended to make older Mooneys more like the 201, with sloping windshields, newer cowls, speed mods and the like.

OWNER FEEDBACK

With the majority of workers at Mooney’s Kerrville, Texas, plant furloughed early last winter, there has been understandable concern—and speculation—about the future support for the fleet of over 7000 registered Mooney models. To find out firsthand, we dialed up Mooney’s Kerrville support line and our call was returned in less than an hour from Kevin Kammer, who leads the customer service division.

“We still make parts and we are fully supporting the fleet right now,” Kammer told us, although he said there might be longer lead times on some components, and vendor shortages could make it difficult to source parts for older models. But, need a skin to fix a Mooney that’s been shredded in a gear-up landing? Kammer said the company can deliver.

“We’re sending out kits—composite and metal bellies—for these field repairs all the time,” he told us. Stamping, cutting and milling—Mooney is making it happen, but with a skeleton crew.

There are also technical support people available for helping Mooney’s nearly 50 service centers troubleshoot and solve problems with the fleet. Shops tell us they generally get what they need.

We asked Kammer (who owned a Mooney 231 for over 20 years) what the most common gotcha is when scoring an M20J (or any older Mooney) on the cheap and not surprisingly he warned of hidden corrosion, especially in fuel tanks and even in the steel frame on airplanes with water intrusion. Still, we’re encouraged that factory support lives on, at least for now.

I have owned my 1979 M20J for ten years and wish I had bought it ten years earlier. This is my fifth airplane and the one that fits my needs better than any of the ones before. Oh sure, I would like to have something faster, roomier, with more useful load and maybe a turbo, but I do not think there is a normal category airplane that does as many things we’ll as my Mooney.

Living on the West Coast, nearly all my trips involve crossing mountains. If weather is no factor, I fly at either 9500 or 10,500 and flight plan for 150 knots at 10 GPH. With full tanks, that is a comfortable 700-NM range with IFR reserves. The extended cabin of the M20J is quite comfortable on long flights. With only two people on board the front seats can be pushed back to where even a tall person cannot reach the rudder pedals. This creates a lot of space for the leg exercises I like to do on long flights. Ventilation is also good and the heater is excellent, even for back seat passengers.

Airplanes prior to 1980 had instrument panels that prevented deep avionics from being mounted near the top of the panel. Two years ago I designed a new panel that integrates an Aspen PFD with my existing (older) avionics. While not as flashy as a new glass panel, it provides an uncluttered layout and the same capability at a fraction of the cost. With ADS-B Out and a Stratus II on a rear window, an iPad mini fits nicely on the yoke and provides a moving map, weather and traffic.

Having flown heavy aircraft for over 30 years, I appreciate the solid feel and stability of a Mooney. I owned a Beechcraft 33 for many years and got used to the “tail-wagging” common to most Beech singles. I was pleased to find that the Mooney has none of that and is an excellent instrument platform.

Most Mooney parts are available from the factory through a network of Mooney Service Centers as we’ll as from many third-party vendors. Numerous modifications are also available, but few are really needed. Deactivating the ram air system makes sense and the one-piece belly mod saves a couple hours at each annual. An LED landing light is also a good addition.

As for maintenance, there are certain things that Mooney owners have come to accept. About every 20 years the fuel tanks need to be resealed. Sealing one leak at a time works for a while, but eventually the tanks need to be professionally stripped and resealed. Likewise, the landing gear “donuts” need to be replaced occasionally. For any Mooney parked outside, it is imperative that the side windows are properly sealed to prevent corrosion of the steel tubing.

The Lycoming IO-360 in the 201 is one of the most proven and reliable engines in the industry. If flown regularly, one can expect it to reach TBO without a top overhaul. Three-blade props do not always get along with this engine. What they gain in climb performance, they lose in cruise speed and often have vibration issues. The two-blade McCauley the factory chose for the airplane has proven to be a good choice. Dynamic balancing can make a noticeable difference in the vibration level in the airplane.

My only recurring problem has been the autopilot. My aircraft came from the factory with a Century 41, which is a full-featured autopilot designed for much larger aircraft. In addition to weighing nearly 30 pounds, it is difficult and expensive to repair. The King autopilots found in most 201s are a better match.

Otherwise, the systems in a 201 are simple, reliable and fairly easy to work on. If something out of the ordinary needs to be repaired, I would recommend a Mooney Service Center. Not all shops have the same expertise in caring for Mooneys. For the past several years, my annuals have averaged $2000. This year my insurance, based on $110,000 hull and $1 million liability, was $975 through AOPA.

Needless to say, I am very happy with my Mooney.

Charles Raines – via email

I purchased a 1987 Mooney 205 in 2018 after sitting in a new Mooney at AirVenture that year. Although I was interested in buying an F model to get my Mooney feet wet, N205MN was available at the same airport/maintenance facility with a dead engine due to a missed AD. After short negotiation with the original owner, a fair deal was struck to somewhat mitigate my additional $55,000 expense to replace the engine with an Airpower factory reconditioned engine with new Power Flow exhaust, separate magnetos, propeller overhaul, oil cooler and engine monitor.

That project took about 10 months, with only one very slowly acquired factory part for the prop cabling bracket due to mag modification. The 205 came with the best of 1987 King Silver Crown avionics including the KAP-150 autopilot, which had some problems. The previous maintenance shop, which missed the engine AD, had evidently lubed the trim cables where the pitch trim motor clamps down. Against all the best advice from Aviation Consumer, I decided to stick with the King KT-76A transponder while adding a Garmin GDL-82 ADS-B out. So far so good; however I did buy a spare KT-76A at a near giveaway price.

The 205 is supposedly 4 MPH faster than the 201 because of inner landing gear doors and upswept wingtips. I have no reference point to judge the winner of that speed contest for myself, but I generally see 148 KTAS at 23 inches MP and 2400 RPM around 5500 or 6500 feet. I suppose I could go faster if I wanted to deal with more prop noise and fuel usage, but that already seems like warp speed compared to the Cherokee 180 that the Mooney replaced.

The rate of climb is pretty darn good averaging about 800 to 900 FPM and I give credit to Power Flow for that. The real issue I see here with attaining book speed is a thrust-to-weight issue. Lighter avionics help, but since everything works so we’ll the upgrade is tough to justify.

As for flying the bird, it’s pretty darn easy. The 140 KIAS gear speed and 132 KIAS flap speeds are quite helpful. It’s slippery on the way down and thinking ahead to plan your descents is necessary.

I don’t know how pilots manage to land J models gear up as it’s challenging to get slowed down enough if you are operating the engine correctly.

A little trick I learned at the MAPA Mooney Safety Clinic for descending is not reducing the MAP below 20 inches, and then reduce the RPM to 2200. Keep your speed up that you lost in the climb because that’s probably why you bought it.

Speed really matters on short final approach and has to be closely monitored. In the flare you have to remember that the plane sits very low to the ground and you don’t want to drop it in from too high. That is a setup for a propeller strike on the third pogo unless you take immediate action. The brakes are very effective and short-field landings are doable.

The rudder has handled some serious crosswinds without issue. Because of the short prop clearance to the ground, I haven’t taken her into any grass/gravel strips, but nicely manicured grass strips without ruts might be fine.

After a year and several long trips, I think it’s a great airplane with long legs and 64-gallon tanks that are stone simple to operate. My annual was $2500 and insurance is $1225 for a $125,00 hull value.

Steve Bulwicz – Bloomington, Minnesota