The late aviation author Gordon Baxter was often heard to opine that when it came to airplanes, speed was what truly mattered. He put his money where his mouth was, owning an early Mooney, one of the fastest, most efficient flying machines that could be wrapped around a 180-HP Lycoming engine.

We think Baxter spoke for a hearty majority of pilots—after all, we think that every one of us has said at least once, “It’s a really good airplane, I just wish it were a little faster.”

There’s a mod for that

We’re in the midst of what appears to be a mania for panel upgrades as owners are dropping tens of thousands of dollars to install avionics that will figuratively lead them by the nose from liftoff to touchdown. Yet, while that investment might occasionally result in a more direct route between those two points, it will not provide any return on investment by increasing the cruise speed nor improving fuel efficiency.

After spending cubic bucks on avionics—and perhaps an interior—to make the family bird just right, is there a way for an owner who has some money left over to make that just right airplane just righter by making it faster?

The chances are better than even that there is at least one speed mod for your airplane that’s worth consideration in that you’ll see a measurable increase in cruise speed and fuel efficiency at a price that makes it worthwhile.

We’ll be taking a look at speed mods for owners on a budget—generally focusing to see whether there’s one mod that gives enough performance improvement to make it worth the money.

Caveats

We’ll begin by recommending caution when it comes to evaluating speed mods. First, although most every pilot thinks of speed in knots, speed mods are advertised in miles per hour because the numbers are bigger. We’re waiting for them to go to kilometers.

Second, we’re wary of speed claims. There’s less hard data on the subject than we’d like and we’ve observed that owner reports can suffer from a certain lack of objectivity.

Nevertheless, over the course of many years we have done what we consider to be objective testing on a number of speed mods and are convinced that most really do give a measurable performance improvement.

That’s because general aviation manufacturers had a finite amount of money available when designing and certificating their airplanes. At some point management had to tell the engineers that what they had was good enough and froze the design. That almost always meant that the design was not optimized for speed—although we think Mooney, Grumman American and Diamond came pretty close. We think that is why we found virtually no aftermarket drag-reducing mods for those aircraft.

Not additive

Also, the benefits of mods are not additive. If one is advertised to improve cruise by 6 MPH and another by 4, installing both will never give a 10 MPH bump.

Finally, it appears to us that most of the speed mods that reduce drag also give some degree or rate of climb improvement. The mods that allow the engine to develop more power such as tuned exhausts and electronic ignition definitely improve rate of climb because climb is a function of power available.

Because speed mods involve what the FAA considers to be a major alteration to the underlying airframe, each had to go through the Supplemental Type Certificate (STC) approval process for them to be installed on a production airplane. However, it must be kept in mind that the STC process does not mean that the developer made the airplane any better—all the applicant had to show was that the mod didn’t make the airplane any worse in terms of handling, stall behavior, stability and control.

The STC approval process does not require any demonstration of—or verification of—new performance numbers. That means that the STC speed mod you buy includes a lot of paperwork regarding how to install and maintain the mod, but it is almost certain not to include any new performance or flight planning numbers.

Before the mod

Having been involved in a number of flight demonstrations and tests evaluating aircraft performance, one thing we learned early on was to make sure that the airplane involved is up to snuff before doing any mods. We don’t know how many airplanes we’ve examined that couldn’t make book cruise numbers because they were out of rig (flying sideways is a high drag condition), engine power instruments were inaccurate, the airplane was dirty, or the prop had been filed so far that it wasn’t converting power to thrust.

It’s not uncommon for some relatively inexpensive maintenance work to bump cruise speed by as much as a speed mod.

Finally, weight and center of gravity matter. Hauling around stuff you really don’t need slows your airplane. In addition, loading the airplane as near the aft CG limit as possible makes it faster. We’ve seen a difference as high as 3 knots between the fore and aft limit in four-place singles. After all, for years aircraft salespeople have been shoving their seats all the way back when demonstrating airplanes to prospective buyers.

We’ll go through what’s available in a moment, but we’ll start with our opinion as to what single mod will give you the most performance improvement for your airplane. It’s our experience that a certain percentage of owners want to do something to make their airplane faster, but they’re on a tight budget, so it’s going to be just one mod, and they want to find the right one.

Doing just one mod

After years of looking at speed mods, our opinion is that the one mod that gives the most performance is something that effectively fairs in the gear legs and tires on fixed-gear singles. Cirrus brought this to the forefront of our thinking when it brought out the SR20, a 200-HP, fixed-gear single that was faster than 200-HP retractable singles.

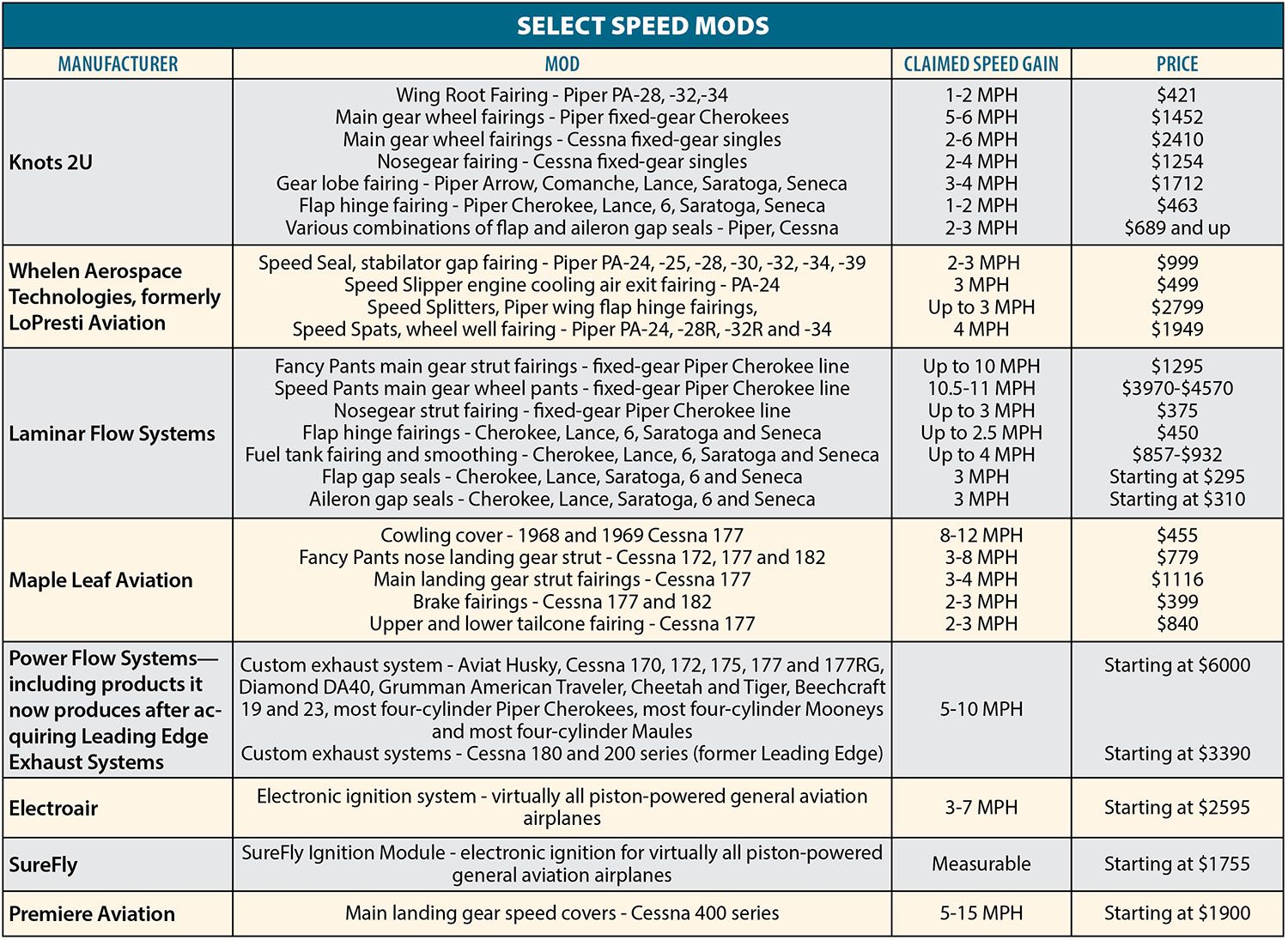

If you don’t have wheel pants to start with, we think you’ll see as much as a 10-MPH speed delta with the various designs for speed wheel fairings that are available. If you have factory wheel pants, switching to an aftermarket version should be good for 3 or 4 more MPH. We particularly like the fairings that include the gear leg in addition to the wheel/tire. Providers include Knots 2U (www.knots2u.net), Laminar Flow Systems (www.laminarflowsystems.com), Whelen Aerospace Technologies (www.flywat.com) and Maple Leaf Aviation (www.aircraftspeedmods.ca).

For most fixed and retractable singles, our next favorite speed mod is a tuned exhaust, such as those manufactured by Power Flow Systems (www.powerflowsystems.com). We’ve flown them on a number of airplanes and the extra power from a tuned exhaust does improve rates of climb and cruise speeds. We note that drag is a squared function, so to double cruise speed, it’s necessary to have eight times the power. However, the power bump from a tuned exhaust has repeatedly shown cruise speed increases in the 5-10 MPH range.

For twins, there’s not a lot out there. The speed increases tend to be a smaller percentage of the existing cruise speed than for singles, although there are some we like. For 400-series Cessnas we test flew the main gain speed covers from Premiere Aviation and observed 5-15 MPH cruise speed increases, depending on altitude and power setting, along with all-engine and single-engine rates of climb improvement. For the Piper Twin Comanche the benefit of “just one” mod is modest. The “Wow Cowl” from Knots 2U gives a 7 MPH increase. However, at $7,995 for a pair before painting and installation, we’re not convinced of the return on investment given the speed and efficiency of the stock airplanes.

Some of the other mods

While we’ve given our recommendation for the one speed mod that gives the greatest speed increase, we’ll survey what else is available, what sort of performance delta might be available and any observations we have on each one. We’ll note that just as your airplane goes faster when you fly higher, the same is true with speed mods. If you’re one who regularly goes to altitude and stays there for some time, you’ll get the most out of whatever go-fast mod you install.

• Gap seals are installed on the underside of the wing in front of the ailerons and/or flaps. They are designed to reduce the amount of high-pressure air on the underside of the wing that bleeds through the gap between the wing and ailerons and/or flaps.

When looking at the airplane from straight ahead or behind, a diagram of the lift generated by the wing shows that the majority is inboard, so flap gap seals are expected to have a greater effect on speed than aileron gap seals. Feedback from the field is consistent with this observation.

For flap gap seals, figure on a 2-5 MPH speed bump and some rate of climb improvement. We were concerned that they might adversely affect flaps-extended stall speeds on Fowler-flap airplanes, but we found no indication that such was the case. Stall speeds reported to us were unchanged.

We received varying feedback on aileron gap seals. Reports ranged from no change to as much as 3 MPH.

What we think is more important is that aileron gap seals dramatically improve roll rate—as much as 80 percent according to Laminar Flow—which is consistent with testing done in 1937 by N.A.C.A., the predecessor to NASA.

Gap seal providers include Knots 2U, Laminar Flow Systems and Maple Leaf Aviation.

- Gear lobe fairings behind the partially exposed, retracted main gear on Pipers. Speed increases were in the 3-4 MPH range. Providers include Knots 2U and Laminar Flow Systems.

- Flap hinge fairings on Pipers—1-2 MPH. Providers include Knots 2U, Whelen Aerospace Technologies and Laminar Flow Systems.

- Fuel tank screw and rivet fairing on Pipers—up to 4 MPH. The only provider we found was Laminar Flow Systems.

- New forward cowlings historically made significant speed improvements on a number of airplanes; however, they weren’t (and aren’t) cheap, so we’ve watched the offerings diminish. Currently they are available for the first two model years of the Cessna Cardinal (8-12 MPH speed increase) from Maple Leaf Aviation and for the Piper Twin Comanche, mentioned above.

More power

Getting more speed via better engine power output at a reasonable price is always attractive. We went into Power Flow Systems’ tuned exhaust above.

The other method available is replacing at least one mag with electronic ignition, which allows adjusting ignition timing that can improve power output and reduce fuel consumption. There are two electronic ignition systems available.

• SureFly Electronic Ignition (www.surefly.aero) is a relatively basic, largely maintenance free electronic ignition system. It provides what we consider to be a measurable cruise speed increase although we consider that secondary to the overall benefits of an electronic ignition system.

• Electroair’s (www.electroair.net) is a high-tech, sophisticated high energy electronic ignition system that increases engine power output significantly through adjusting ignition timing and boosting spark output. While we describe cruise speed increase as “measurable” we have had reports of 3-9 MPH improvements.

In addition, the added power during climb results in an increased rate of climb and service ceiling. We note that aerobatic pilot Spencer Suderman was able to set the world record for inverted flat spins—98 turns—after installing the Electroair system in his Pitts.

It improved power output in the normally aspirated engine enough to get him to 24,500 feet to start his spin. He’d previously topped out at 21,000 feet.

Conclusion

Before shopping for speed mods, spend a little time ensuring your airplane is not working against itself with drag from misrigging and that the engine power gauges are accurate.

For a fixed-gear airplane, we think the most effective speed mod consists of aerodynamically refined gear and wheel fairings.

Otherwise, we’d look hard at a Power Flow tuned exhaust and/or the Electroair electronic ignition for the combination of power and speed increase and its value in getting rid of the cost of maintaining one magneto.

OK, you’re getting ready to buy and you want speed. The aerodynamically clean Mooneys and Cirrus line are outside of your budget. Is there something that you can buy with enough budget money left over for speed mods that will boost your machine into the next speed level?

With a certain level of caution, we think that with some careful shopping, the Piper Cherokee 140 could make it happen for you.

We’ll start with a 1969 Cherokee 140 (PA-28-140), powered by a 150-HP Lycoming, with a Bluebook value of $64,000. Real-world cruise speed for the pleasant little beast is on the order of 110 knots (127 MPH). For this exercise we looked at a step up in the cruise speed world to the 180-HP Lycoming engine powering the Cherokee Archer (PA-28-181). Bluebook value for the first model year with the tapered wing, 1976, is $90,000. We consider a real-world cruise speed for it to be 125 knots (144 MPH).

With a roughly $26,000 price delta, is it possible to make a Cherokee 140 as fast as or faster than an Archer and have change back from your investment?

We think so. Here’s why: Back in 1985 the then editor of Aviation Consumer traveled to Laminar Flow Systems (www.laminarflowsystems.com) to make a flight test of a Piper that had been modified with the company’s speed kits—a Cherokee 140.

The lowliest Cherokee had received the following Laminar Flow kit:

• Fancy Pants main gear fairings that enclose the exposed gear struts and brakes and are more aerodynamic than Piper wheel pants—they fit over the existing wheel pants.

• A nosegear fairing covering the lower nosegear strut.

• Flap hinge fairings that enclose the exposed, high-drag flap hinges.

• Wing fairings that enclose and smooth the area of the exposed screws and rivets along the fuel tanks.

• Aileron and flap gap seals that close the gap between the wing and the ailerons/flaps, reducing the amount of high-pressure air under the wing that escapes upward through the gap.

• Tuned exhaust kit (the kit in use at the time evolved and is now marketed by Power Flow Systems—www.powerflowsystems.com).

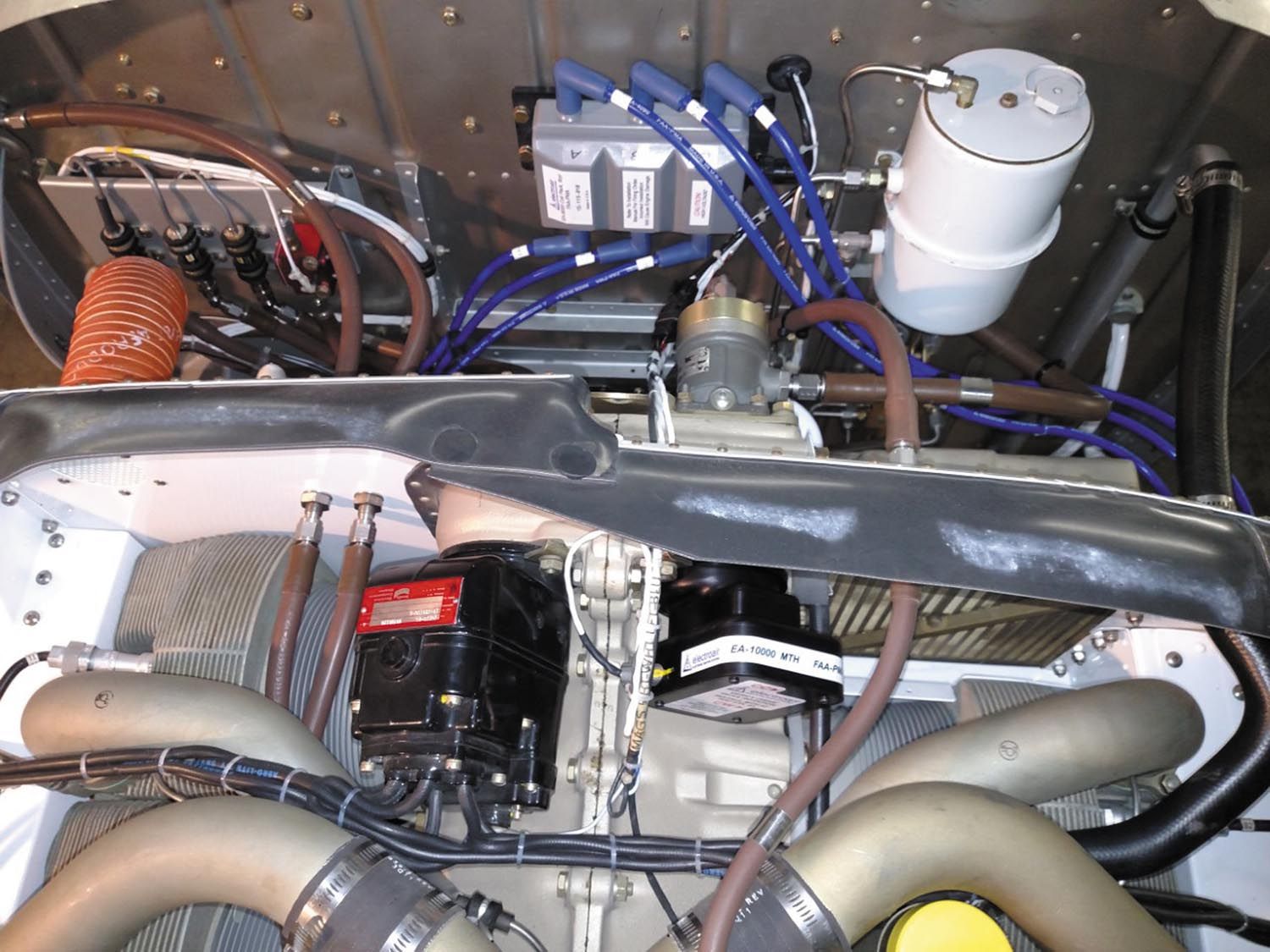

All of the mods listed are installed on the PA-28 pictured below.

Our editor reported, accurately we think, a cruise speed increase in excess of 20 MPH. (The max cruise he reported was 155 MPH.)

Based on the 1985 report, the modified Cherokee 140 was measurably faster than a stock Archer.

Sounds great—what does it cost?

Currently, Laminar Flow offers the complete speed mod kit, which includes all of the above mods, except the tuned exhaust, for $3291. We note that the parts will almost certainly need to be painted, but having seen so many examples of general aviation paint jobs, including brush strokes on a rural Louisiana Cessna 150, we aren’t going to make an estimate for the cost of painting.

We think 50 hours is a reasonable estimate for installation of all the mods. At a shop rate of $100 per hour, that’s $5000.

Power Flow Systems offers some discounts for its tuned exhaust, and they currently result in a price of about $6000. For installation, figure 10 hours, so add $1000.

Bottom line—we think that a Cherokee 140 can be made 20 MPH faster for on the order of $20,000, making it speedier than an Archer for $6000 less than the price of buying the earliest model year of the taper-wing Archer.

Although the Power Flow exhaust does mean that the 150-HP Lycoming is going to be putting out more than 150 HP and its fuel burn is going to increase slightly, we think that the modified Cherokee 140 will outrun the stock Archer and burn less fuel.

We note that because the Archer has more power, it will still outclimb the modified 140 and get to altitude sooner. You can’t have everything, although we think this sure comes close.

Then … there’s that nagging thought that came to us late one evening: Why not just buy a slippery Grumman-American Cheetah? Those have a 150-HP Lycoming; are, in our opinion, way undervalued (we saw prices for 1976, the first model year, of $70,000); and they are faster than an Archer.

Maybe we were wrong when we said that there was no free lunch when it comes to speed at the low end of the single-engine spectrum. Just buy a Grumman.

—Rick Durden