Spot on with the marketing that the new Kodiak 900 combines DNA from Daher’s TBM and Kodiak 100 outback turboprop into one airplane, the clean-sheet 900 introduced at AirVenture last summer for certain is not a replacement for the Kodiak 100 Series III bush plane.

Instead, the new FAA Part 23 certified Kodiak 900 is a fitting option in a healthy lineup of Daher turboprop singles, perhaps sitting between the Kodiak 100 and the TBM 910.

To see what the new Kodiak 900 is all about, I recently spent some time with a 2022 demo and Daher Kodiak’s chief demo pilot, Mark Brown.

PERFORMANCE INJECTION

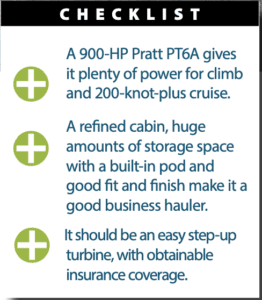

That starts on the business end of the Kodiak with a Pratt & Whitney PT6A-140A turboprop that makes 900 shaft horsepower, continuous through takeoff and climb. Check that against the 750 SHP -34 variant used on the Kodiak 100 Series III, and the 850 SHP Pratt that’s on the TBM 910.

The 900 has a five-blade Hartzell composite propeller, instrumental in lowering noise so the airplane can operate in regions around the world where there are stringent noise regulations.

All of that power pulling the Kodiak 900 doesn’t hurt when it comes to short-field performance, and it’s very much a STOL airplane. At ISA conditions with no wind at its 8000-pound MTOW (max takeoff weight), the 900 gets off in 1015 feet while clearing a 50-foot obstacle. The book calls for a 1724 FPM climb rate under the same conditions. At 10,000 feet, it’ll still climb at 1273 FPM. Certified ceiling is 25,000 for the non-pressurized 900, which is equipped with built-in oxygen.

Impressive is that Daher Kodiak was able to achieve a max cruise speed of 210 knots true at 12,000 feet at MTOW with no wind. That betters the Kodiak 100 Series III by at least 40 knots at the same altitude, and that speed gain was accomplished through a variety of ways. Engine air intake and outflow is an important aspect to drag reduction, so the 900 has a redesigned front engine cowling. The other component of the speed increase (and the most noticeable difference to the new 900) is the pilot-removable wheel fairings, which are good for around 10 extra knots.

AIRFRAME DESIGN

As you would expect from a Kodiak, this is a rugged airplane. Even the new wheel fairings are robust enough to stand on so you can more easily get to the single-point fueling panel under the left wing. It’s a high-pressure system for quick refills—from empty to full capacity (322 gallons) in around three minutes.

The 900 can still land on unimproved strips with the wheel fairings on, so there isn’t really a need to remove them. If there is, you probably should be flying the Kodiak 100 instead, which is still intended for extreme conditions. The 900 has smaller tires with higher air pressure, which can still handle grass and gravel, but you won’t be taking it into gravel bars in Alaska. Still, the 900 and 100 share the same stall-resistant wing and the same empennage. To help reduce drag, the 900 has flap fairings. Control surfaces are cable- and pushrod-driven.

A big redesign on the Kodiak 900 is the integrated three-bay cargo pod. There’s no option for the pod because it’s smartly and smoothly built into the airframe. Even better, there’s a pass-through between bays two and three, plus the third bay has a lower hatch (in addition to the side door) to help easily load in long items like skis, paddleboards, lumber and other stuff that wouldn’t fit through the three side doors of the pod. You can still pile stuff on top of the lower door—180 pounds worth.

CAVERNOUS CABIN

Passengers enter the main cabin through a dedicated door and Daher Kodiak added a third step to the door because the airplane sits higher. There’s a also a handhold to help get in and out. The cabin door can also fold flat for easily loading in stretchers or big stuff into the cabin.

Typical cabin accommodations are for one pilot and nine passengers, and the airplane I flew was equipped with an Executive cabin with double-row seating. It’s a big step up in luxury from earlier Kodiak 100 airplanes, for sure. It starts with redesigned (and easily removable) seats that can be positioned fore or aft. The cabin has been stretched nearly four feet longer than the Kodiak 100’s cabin. The company listened closely to what customers want from a cabin in an airplane that’s priced over $3 million—rugged or not. The result is a redesigned cabin with useful amenities, including removable (no tools required) reclining seats with dual armrests, automotive-style seat belts (no airbags?) and far more comfort than previous Kodiak models. There’s a lot of flexibility to configure the seats the way you want for a given flight, and the only thing the seats can’t do is swivel. Loading bicycles (or small motorcycles)? Pull some seats and load them in. When the seats are all forward facing you gain some useful storage area in the rear of the airplane. Total cabin volume is 309 cubic feet and it’s 4.6 feet wide, 4.9 feet high and 15.10 feet long.

Every seat in the cabin has an amenity panel equipped with two USB charging ports (USB-A and USB-C), plus Lemo jacks for single-plug Bose headsets—no batteries required. And every seat has the obligatory cupholder, of course.

One thing that pilots and passengers of cargo-hauling airplanes love are tiedown anchors and the Kodiak 900 has no shortage of them. The designers weren’t stingy—you’ll find them almost anywhere you look in the 900’s cabin.

Perhaps what I like best about the Kodiak 900’s cabin is the size and placement of the rear windows. While seated, your eyes are right at the perfect level for looking outside. No hunching down for a good view outside and the large windows make the already cavernous rear cabin a more spacious dwelling.

Last, I don’t know a single aircraft technician who doesn’t cringe at the thought of removing an interior headliner—especially a new one. But it’s easier in the Kodiak because there are dedicated built-in inspection panels in the two-section headliner that make it easier to access areas that need frequent inspections. This should keep the headliner in decent shape for the long haul, and save time on the shop floor.

FLYING IT

With the big PT6A fired up and the Kodiak out of chocks, steering is predictable thanks to a steerable and castering nosewheel. On a side note, the FBO at my airport in Connecticut (equipped to move all kinds of jets and turboprops) didn’t have the right tow bar to move the new 900 and it wisely didn’t attempt to. Ask line services if they have the right tow bars, regardless of the airplane.

The 900-HP Pratt gets the airplane’s 8800-pound ramp weight rolling right along, and it’s useful having propeller beta/reverse to help slow it down without riding the brakes. The free-castering nosewheel is steerable to roughly 17 degrees either side of the centerline, and it’s easy to pivot for tighter turns.

Flying the Kodiak 900 is a comfortable experience, partly because of a good climate control system. Kodiak got the air conditioning system right in the 100, and it’s even better in the 900. The heating system has been redesigned for bleed air heat throughout the entire cabin. An electronic control head makes for easy control, while the bigger engine pushes more bleed air heat.

What’s surprising is how quickly the 900 gets up to the 60-knot rotation speed during a normal takeoff and into an authoritative climb. Lightly loaded at ISA+6, the climb rate was around 1900 FPM through 11,000 feet. The Garmin G1000 NXi’s engine instrument system has a horsepower readout, which showed the engine still producing 880 HP we’ll into the climb. It’s a good airplane for skydiving ops with all that climb rate.

The Kodiak 900, at 8.5 to 1, has a similar power-to-weight ratio as the Pilatus PC-12 NGX. Without the right transition training and mindset, it’s a lot of power to manage for those coming out of the piston single world. Still, I couldn’t help but think the fixed-gear Kodiak 900 could be a good step-up turboprop, even with all that power.

With a wing that you have to try really hard to stall and the envelope and underspeed/overspeed protection that’s built into the Garmin GFC 700 autopilot (also factor the simplicity of no pressurization), it shouldn’t be a handful to fly. Since the Kodiak 900 has the G1000 NXi system, the airplane doesn’t have Garmin’s Emergency Autoland, and it doesn’t have autothrottle. Curious, I asked Mark Brown why the 900 didn’t get Garmin’s G3000 suite, which supports Autoland and autothrottle, and he said it was a cost decision. Daher’s flagship TBM 960 is so equipped, and called HomeSafe.

New to turbines? Be mindful of managing the torque. This one doesn’t have FADEC, which means tightly setting takeoff power. The engine display makes it easy to set everything to the top of the green, and the propeller stays full forward the entire flight. And the five-blade composite Hartzell does an impressive job of taming vibes and cabin noise. With 100 percent of the power available from takeoff through the climb, managing the engine is about as simple as it gets. Monitor the torque and ITT through the climb and keep them set in the top of the green. In terms of stepping up from high-performance pistons, especially turbos, it’s less workload. No shock cooling, and with the good inlet airflow, inflight restarts should be quick, and shutdowns are cooler.

On shorter flights, pilots might fly this airplane between 8000 and 12,000 feet where it still easily cracks 200 knots, but up higher it really shines, and 210-plus knots true is a reality. Incidentally, at 210 KTAS the book says a no-wind max-fuel range with reserves and with one pilot at MTOW is 969 NM, or a 4.3-hour endurance at 12,000 feet.

Efficiency, Daher Kodiak says, was a driving reason to use the -140A variant PT6A. It has 35 more horsepower than the -140 on the same fuel consumption. The sweet spot for efficiency, says Brown, should be obvious on 200 to 500 nautical miles. You’ll burn fuel down low—roughly 450 pounds per hour, or around 54 gallons at 8500 feet.

The 900 has TKS anti-icing and the Kodiak makes it easy to manage. By creating a time/fluid consumption algorithm, it’s easy to know how much fluid endurance you have.

When it’s time to land, step-up pilots should have no trouble keeping up with the airplane because you can slow it down to piston airplane speeds. There’s 35 degrees of flaps, and you slow to 65 to 70 knots on final. The book says the landing distance is 1460 feet over an obstacle with no wind, and with good brakes and beta you can get the Kodiak stopped in a hurry. Bring your A-game.

WHO IS THE BUYER?

Daher Kodiak thought long and hard about that—and safety—when it certified the 900 to the latest Part 23, Amendment 63 standards. “Fire testing, G testing—multiple test airplanes—the Kodiak 900 has been through the certification wringer,” Mark Brown told me.

To that end, nobody can argue that Daher’s oversight of the Kodiak product isn’t a good thing. After all, it has proven with the hugely successful TBM product line that it knows how to make turboprops go efficiently fast with a healthy dose of styling and standard tech. And not insignificantly, it knows how to support the product and treat the customer.

Will that attract even more buyers to the new $3.5 million Kodiak 900, perhaps step-up pilots who might be eyeballing a Cirrus Vision Jet? I think it might. Brown made it clear, though, that the new 900 doesn’t seem to be stealing sales from the Kodiak 100 Series III turboprop. That airplane still does and always will serve a different mission than the new Kodiak 900.

Want one? Get in line. At press time, deliveries for Kodiak 900s are scheduling out two years.

See a video of the Kodiak 900 at http://tinyurl.com/j95ht2a