Not so long ago-about six years to be precise-we were reporting on electronic flight displays as the next big thing. And to be honest, we werent sure if the idea would stick. It did. Now that were into the third-or is it fourth?-generation of this technology, its fair to examine what users think of it. Glass is now standard equipment on virtually every new airplane sold by a major manufacturer. Garmin is by far the dominant provider, but Avidyne sells plenty of systems, too. Lately, Aspen Avionics has made a dent in the aftermarket with its well-regarded Evolution system and a couple of OEMs have picked it up for new airplanes. With all that glass out there, the obvious question is has this technology delivered on its promise? Are buyers and users happy with it? What do they like about it? What don’t they like? Is the stuff just a nightmare to maintain? To find the answers, we published an in-depth set of questions on our electronic news service site, avweb.com. The questions covered a range of topics and 330 owners and pilots replied. In this article, we’ll analyze the responses to our survey.

What We Asked

Avidyne pioneered glass for small aircraft when Cirrus introduced the Entegra system for the SR22 series in 2003. Garmin followed two years later with the G1000 and other systems have evolved during the period, including Cheltons Flight Logic and, more recently, the Garmin G600 and Aspen Evolution, both intended as aftermarket retrofits. Several readers asked why we didnt survey systems from Dynon, Grand Rapids, TruTrak and others. Simple: Were interested only in certified systems for this exercise. We asked a total of 42 questions, ranging from general queries about overall satisfaction with the fundamental idea of EFIS in the first place to more detailed questions related to the design of the displays, maintenance issues and cost-value relationships. Survey respondents were given ample opportunity to comment in their own words and many did.

Worth noting is that our survey consists of self-selected respondents. In other words, we werent able to stratify our sample in such a way that it represents an accurate reflection of the entire EFIS-using population, if such a sampling is even possible. Nonetheless, we still think reader responses have merit.

Hey, We Love EFIS

A first look at the big picture reveals that users of this technology are overwhelmingly happy with what it does, generally satisfied with how it works and even though glass displays are quite expensive when compared to the avionics that preceded them, owners see good cost-value in glass panels.

Eight out of 10-84 percent to be exact-said they thought that the current generation of glass panels had lived up to their expectations and a slightly smaller majority-62 percent-said that EFIS displays have materially improved flight safety when compared to the steam gauges they replace. If there’s an emperor-has-no-clothes vein in the world of EFIS, our survey didnt reveal it.

Only 8 percent of our survey respondents characterized electronic flight displays as overrated or over- hyped. Given the number of complaints we heard about complexity of operation and difficulty with training-more on that later-we conclude that users are so impressed with EFIS capability, theyre willing to overlook significant design and interface warts.

An equal percentage of owners-85 percent-told us they thought the EFIS systems they had flown significantly improve flight safety, while the remaining 5 percent thought it had no impact or actually degraded flight safety. That last finding is illogical unless you read the comments: A small fraction of users believe that EFIS technology is so difficult to master and demanding of pilot attention that it represents a distraction and thus detracts from flight safety. While this is clearly a minority view, it does address a theme we found throughout our research: Even users who like EFIS technology complain that its operating logic is occasionally not logical at all or frustrating to use.

Market Share

Although Avidyne jumped into the EFIS fray early with Cirrus, Garmin focused its vast marketing and developmental machine on the glass segment and produced the G1000 in 2005. This product has since dominated the field. Its available in airframes from most of the major manufacturers. Of the 330 users who replied to our survey, 57 percent were Garmin G1000 users, 25 percent were Avidyne users and rest were divided between Cheltons Flight Logic, Aspens Evolution and the Garmin G600.

Customer satisfaction levels between these systems seem fairly comparable, although our survey suggests that those who like the Avidyne Entegra like it a little

more than Garmin users like the G1000. Seventy-nine percent of G1000 users said their expectations were fully met, while 86 percent of Avidyne users said the same. (Well concede that the Avidyne sample size was smaller, but data is data.)

Our impression that Avidyne users are marginally more enthusiastic about the Entegra than Garmin users are about the G1000 was supported by comments. The G1000 has a certain strain of love-hate.

“It has a horrible user interface compared to whats acceptable in computers, with the iPhone or the Mac, for instance,” wrote Dave Passmore. “The Garmin G1000 is too complicated,” added Byron Wardropper. Yet…both readers checked the box answering that their expectations of the G1000 were fully realized.

Overall, the G1000 seemed to draw high marks for its notional design and performance while also collecting brickbats for how difficult it is to make the thing play at times.

Our survey put an exclamation point on what we already knew: Its the airframe manufacturer who drives EFIS choice more than aircraft buyers do. If one company-that would be Garmin-approaches a Cessna, a Cirrus or a Mooney with a competitive price on new avionics, thats what the airplane will have, whether the customer demanded it or not. Even though some airframers give the choice of Garmin or Avidyne, 58 percent of users said they had no choice in the type of glass panel the airplane had because it came equipped that way. Twenty-five percent picked the EFIS they use based on features and some of these owners bought a Cessna 182 because it had a G1000 in the days before Cirrus offered the Garmin option.

Experience, Training

Although there’s a lot of glass out there, our survey suggests that there’s still not a vast pool of glass-experienced pilots. Forty-two percent of EFIS pilots reported having under 100 hours with these systems while about the same percentage reported between 100 and 500 hours. Only 14 percent had more than 500 hours.

Experience notwithstanding, if there was an area of consistent complaint, it related to training and keeping current on cutting-edge glass systems. We know that Cirrus, Cessna and other manufacturers include training as part of the aircraft purchase, but we were surprised to learn that only 24 percent of survey takers said they were factory trained. The rest were self-taught (29 percent), trained by a local CFI (23 percent) or trained through a computer-based training system (23 percent).

“Training with a glass-proficient CFII should be a must before you try the clag by yourself,” wrote Dan Luke. Added another reader, “The Aspen manual is clear and straightforward. Not so much with the G1000. That I needed an outside CD to master.”

Factory training got mixed reviews. Some said it was great, others less so, some in between. “Cessna factory training was excellent, but there is too much emphasis on autopilot and trying to show you everything the G1000 can do. Best to focus on one or two ways and not six ways,” wrote Joe Brown.

The more important question, in our view, is this: Once the training is completed, does it stick? Here, EFIS technology got less than a ringing endorsement. A little more than half said training for them worked as a one shot deal, but nearly as many-45 percent-said they need recurrency or constant refreshment. So whats the problem with that? All pilots need recurrency training. Heretofore, pilots have undertaken recurrency to keep sharp on procedures and muscle-memory skills-tuning the radio was a given. But a box as complex as the G1000 requires more repetitive practice than many owners expected going in.

“Glass panels require a lot of consistent usage. Its comparable to using a computer program. If you don’t use it every day, you wont know all the features or be proficient in operation,” wrote John Reynolds. “Flying once a month wont do it,” adds Scott James.

Few users said this training requirement is a deal breaker, but owners who fly infrequently should heed this warning and not underestimate what it takes to stay sharp.

Design, Ergos

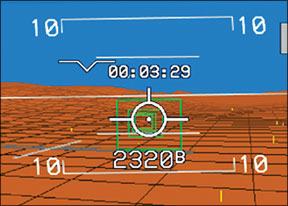

When glass first appeared-and still-it used digital technology to essentially mimic the look of steam gauges, but in living color. Are buyers happy with that? Or would they prefer something new and different?

“Simple electronic display of mechanical gauges is not going to change flying or flight safety very significantly,” wrote Tim Olsen. But several other readers challenged our basic assumption: “The G1000 doesnt mimic mechanical flight instruments,” wrote one owner. We take the point, but the only real difference

between the electronic display on a G1000 and an iron AI/DG combination is the altitude and airspeed tapes. Speaking of which, do users like these tapes? Generally, they seem to. Fifty-seven percent of the survey takers say they would keep airspeed and altitude tape displays just as they are, 15 percent would prefer electronic representations of analog instruments and 29 percent would like to have-surprise-the pilot option of configuring them either way.

Interestingly, through no particular research into human factors, the manufacturers generally-although not universally-represent power instruments as round dials rather than tapes. Do owners want the tapes or the dials? The dials, it turns out. Forty-seven percent prefer the dials to only 17 percent for tapes. We wonder if pilots just get used to anything you throw at them. Maybe, but it might take some effort. And pilots who took our survey said as much. More than half (55 percent) thought it was easy and natural to adapt to the altimeter and airspeed tapes, but 37 percent said it took a lot of effort to make sense of the tapes.

“Actually, I find it easier to eyeball an old altimeter, as small deviations are not really distracting. I got used to the tapes,” said Juan Del Azar.

Zooming out to the megaview, we asked users to tell us their opinions of the design of the PFDs and MFDs these systems typically have. Are they we’ll thought out? Too cluttered? Easy or hard to use? Considering the complexity of what PFDs and MFDs have to do, we think the manufacturers got these displays right, with a few niggling exceptions. About two-thirds of users said the design of PFDs was really brilliant, just a little less than a third said “good, but not exceptional.”

“Pretty good in general, but I wish the engine gauges were larger,” wrote Alex Ho. “On a PFD, I think a common mistake these days is to add too many color shadings and aesthetic touches for wow value that actually decreases the safety of the system. The Chelton system to some would seem primitive with wire frame terrain, but it has by far the best quick scan and readability of any PFD on the market. I am glad they don’t have shaded terrain and things like the newer systems. I think those will prove to decrease safety,” added Tim Olson.

“The G1000 has some really dumb things-its way too easy to delete all flight plans by mistake-missing essentials such as airways (now an option) and downloadable engine data,” wrote David Johnson.

We also asked about the design of the MFD. Does it function we’ll as placed in the center of the panel? Yes, said 84 percent of respondents. Is the display logical and we’ll designed? Maybe not so much. Fifty percent rated the MFD design as excellent, 42 percent described it as good. The two biggest beefs were that the MFD operating logic is confusing and there are too many pages to scroll through.

“Still too much clutter on some map modes,” observed Scott James. “Multi-function is good, I would prefer a push button instead of changes by turning knobs . Push buttons are faster, ” added Manfred Brecker. “The multi-function certainly improves situational awareness, however one real danger with this and other technologies that we are seeing today is that the pilot runs the risk of becoming a player of a video game and no longer uses his brain to envision the airplane in its actual environment and flight regime,” wrote Bruce Bell.

Maintenance, Upkeep

If there’s a substantial undercurrent of dissatisfaction related to surprise maintenance of glass systems, our survey didnt detect it. Forty-one percent described the systems as “surprisingly low maintenance” and 44 percent said maintenance was about what they expected. A total of 15 percent said the maintenance incidence was worse or a lot worse than expected. Given the complexity of these systems and their relative newness, we think the manufacturers have done better than expected on durability. Weve heard scattershot complaints and thought that a survey would tap more than a trickle of beefs. It didnt.

Overall, 26 percent reported having no maintenance incidents, 47 percent reported one or two incidents, 15 percent had three to five and 6 percent had more than five. The manufacturers seem to have stepped up in owners eyes, setting right broken boxes or consulting on novel problems.

“We had some early trouble with the AP, but Garmin stepped up and made the situation right. No troubles in over 500 hours,” wrote one reader of a G1000. But we heard complaints about both Garmin and Avidyne service policies and responses.

“Avidynes failure rate was far too high early on. With Release 7.0, its been improved significantly, plus recently Avidyne and its Mike Glover have really gotten the religion about customer service,” wrote Bob Bowen.

“Garmin was less than honest about the process of upgrading to WAAS,” complained Eric Thompson. “We were led to believe when we purchased the plane that this would be a simple software patch, but it turned into an expensive box swap plus software. Many Diamond owners were frosted about this and felt misled.”

Comparing Garmin against Avidyne for relative rate of service complaint yielded

similar results. About 8 percent of Avidyne users had service complaints compared to 6 percent for Garmin.

If customers are consistently steamed about one thing, it would be database revisions. Nearly two-thirds (63 percent) said they buy the revision on a “grin-and-bear-it” basis, while 29 percent termed the revisions worth it and a good value.

Some choice comments: “Why, for example, must I pay $400/year for NACO approach charts on a G1000? Why cant the system import PDF files from the web? Also, the software for downloading Garmin data off the internet and placing it on SD cards is hard to use due to their paranoia about it being duplicated too easily (DRM),” complains Dave Passmore.

“Garmin and Jeppesen each have their own readers, even for the same type cards. How paranoid can you get?” says Paul Diamond, a G1000 user.

“We pay too high a price to get data weve already paid for as tax payers. A fee to convert public data into a format needed by the machine is fine, but Garmin and Bendix/King are over the top,” writes Alan Williams. We could go on, but we’ll stop now.

Conclusion

With some exceptions, our survey reveals that the market has warmly accepted and adapted to EFIS as more or less the standard for new aircraft. Typical of the overriding sentiment is a comment from David Paul about the G1000, but which could just as easily apply to any glass:

“I wouldnt purchase an airplane without a G1000 system. I still fly steam gauges on a simulator once a month and I am amazed how primitive that seems to me now. And I can also see how much higher a workload steam gauges are in single-pilot IFR. The G1000 is a significant advance in situational awareness, lower pilot workload and ease of navigation. The voice call-outs for baro minimums, the lower workload involved in executing a missed approach and the integration of traffic, terrain and obstacles on the PFD in the SVT upgrade represents a significant advance in safety.”

We received dozens of other comments like this, along with a few-very few, actually-dismissing glass technology as not much of an advance at all. We expected to find more complaints about maintenance incidents and failures but, encouragingly, we didnt. Owners seem to be realistic about what their glass panels can do and what it will take to keep them flying safely.

We see three shortcomings in industry efforts to field EFIS: training, data revisions deemed as overpriced and not needed and interface designs that are too complex and illogical to use. In our view, training is the biggie here. While its true that there are plenty of training options out there-including computer-based systems-we sense that pilots either don’t find these appealing to use or don’t find them effective. Many pilots say that learning these systems and staying current isn’t onerous, but we cant say that most say that. Learning the systems is work that not everyone relishes.

Complaints about paying for government flight data have always been there but they are being brought to a head by glass technology, as owners realize they have to shuffle data cards and/or fool with internet portals that arent always transparent. This problem begs for a solution brought by additional competition, but we don’t see that on the horizon just yet.

Last, the complex interface complaint. Garmin actually addressed this in the G600 and so did Aspen. Avidynes Revision 9 is also easier to use. (We didnt survey that system because there are too few flying.) In reading user comments, we sense that over-complex interface design is a low-grade complaint, but it is consistent and probably relates to the larger problem of training thats not quite on the mark. However, help may be on the way. Were seeing ever more glass panel training programs and sooner or later, there will be enough choice to meet even a confirmed Luddites cranky requirements.