When Diamond was hard into its certification of the DA42 Twin Star in 2005, it knew it was taking a big chance on the untried Thielert 1.7 diesel engines. But it also hedged its bets by running a near parallel certification effort of the same airplane fitted with Lycomings angle-valve IO-360, a we’ll proven powerplant. It back-burnered the Lycoming project once it appeared that the diesel engines were both preferred and were gaining ground in the market. It now appears as though the Lycoming hedge is paying off, by necessity. As is we’ll known by now, the Thielert diesels turned out to have a spotty service record at best, a disastrous one at worst. The engine required numerous periodic replacement parts-mainly gearboxes and clutches-but also lots of unscheduled (and expensive) maintenance that all but tanked the 1.7 diesels as serious contenders. As we go to press this month, Diamond is finishing certification details on the resurrected Lycoming project under its new version of the airplane, the DA42-L360. (The trade name Twin Star has been dropped because of a trademark dispute with a helicopter manufacturer.) The Lycomings will be offered as an option in place of the newly certified Austro AE300, which Diamond also brought to fruition by launching a company just for that purpose. The new engines will be available for both new aircraft and owners of existing Thielert diesel models who may wish to convert. (We suspect many will.)

Fish or Fowl?

Diamond would prefer that the L360 be compared with other twins in the training market, namely Pipers Seminole, the only real competition. We see the point, but we also maintain that this comparison simply wont fly, at least for our purposes. Thats because the original DA42 was born as a Thielert diesel-powered airplane. Just as the airplane was developed for the diesel, its also true that if the Thielert engines hadnt done so poorly in the field, the Lycoming version of the airplane wouldnt exist.

Response to the diesel was so strong in 2005 that Diamond saw no need to continue with the Lycoming version. There was no interest in it in Europe and even in the U.S., where you can hardly find, much less buy, an automotive diesel, interest was also flat. Still, Diamond knew that the 180-HP Lycs were a good match for the DA42.

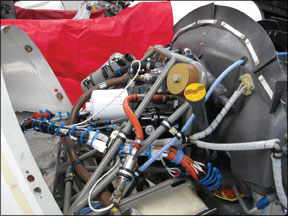

Fully dressed, the gasoline engines are about 50 pounds lighter than the Thielert diesels and the installation is accordingly simpler. There’s no plumbing for a cooling system, no FADEC and its associated wiring, no gearbox and no backup battery. Lycoming four-bangers are what theyve always been: Gray lumps of rotating parts that turn out torque.

With the original DA42 as the starting point, the Lycomings are attached to the same firewall, albeit through a Dynafocal mount rather than the four-point mount

the Thielert used. The L360 airplanes get new upper and lower cowlings, but Diamond generally retained the look of the diesel cowlings, with a closed lower nacelle and a functional upper outlet grate. There are also small vents on the upper cowling structure.

Unlike most conventional gasoline engine cowlings, which draw air through front inlets and vent it out the bottom cowling, the L360 routes it serpentine fashion through the front inlets, down through the cylinders and back up behind the accessory case where it flows overboard topside. This scheme seems to produce well-cooled cylinders, but oil temps that are on the low side. We would prefer to see 180 degrees-plus on the oil, but we saw less. Some baffling tweaks would fix this and that will be needed for serious winter flying.

Systems

Speaking of which, for heaters, the airplane uses conventional heat muffs, not the combustion heaters typically found in twins. Diamond is considering that option if customers request it. There appears to be more than enough room in the engine nacelles behind the accessory case for a combustion heater. As it obvious from the photo on page 6, accessing the engine for maintenance is a mechanics dream. The L360 is also fitted with the PowerFlow exhaust system, which Diamond has used with good results on the DA40.

To simplify both conversions and the manufacture of new airplanes, the L360 retains the systems found in the original diesel airplane with only minor changes. The FADEC wiring harness is gone, along with the diesels return fuel line. But the fuel system itself remains unchanged, with aluminum cells lodged between the wing main spars for good crash protection and aux tanks in each nacelle. Counting the two 13.2 gallon aux tanks, fuel capacity is 76 gallons, same as the diesel. Because of its miserly fuel burn, the diesel airplanes had excellent range for a light twin. The Lycoming version, by comparison, will have endurance of about 3.5 hours, with reserve. Call that 550 miles in still air compared to a solid 1000 miles for the diesel. Thats more than adequate for most training and is acceptable although not exceptional for a traveling airplane.

The engines are Lycomings IO-360-M1A, a four-banger with a sterling reputation for durability. The right engine is counter-rotating so there’s no critical engine on the L360, something the diesel version couldnt claim, although both variants have as benign Vmc and single-engine behavior as weve seen in any twins.

Diamond tested Hartzell two-blade metal props for the L360 and may make these available as an option, but the standard props will be three-blade feathering MTs, which are carbon-clad wood-core props with metal leading edges. These provide better static thrust than two-blade props and Diamonds test data shows that cruise differences between the two props are a wash. The props have an oil-charged accumulator for unfeathering a caged engine.

Choices

In moving forward with this project, Diamond is giving customers unprecedented choice in powerplants to fit the same airframe. Customers buying new DA42s can choose between the Lycoming engines and the recently certified Austro AE300 170-HP diesel. The latter is not yet certified in North America, but Diamonds Peter Maurer told us the company hopes it will be by late 2009 or early 2010.

Customers who now own Thielert-powered DA42s have three options: They can stick with the Thielert 1.7 or 2.0 engines, convert to Austros or convert to Lycomings. Presumably, all Thielert customers will reach this decision point because those engines simply havent proven durable. At best, they require frequent clutch replacements and gearbox inspections and replacement. At worst, many owners have experienced premature failures that require complete engine replacement.

As it works through its insolvency, Thielert-now called Centurion-is providing engines and parts, but costs are high and warranties are iffy, if they exist at all. Owners sticking with Thielert/Centurion will need to be exceptionally patient, in our view.

The competing deal from Diamond? Owners can convert to Lycoming engines for a flat $125,000, all in. For Austro diesels, the bill will come to $140,000 to $145,000. Both options are immediately available, or will be once all of the certification paperwork is completed.

Judging the value of these three options is muddied by the fact that we don’t know when or even if Centurion will deliver on its promise of a life extension program that

will make the 2.0 engines more durable and less expensive to operate. Second, although the Austro will come out of the blocks with a modest TBO-probably in the 1000-hour range-we don’t yet have an inkling of how its life extension program will unfold. Similarly, its service history is a blank page.

Flying It

But the IO-360s service history is we’ll known and quite positive. So how does it perform in the L360? To find out, we flew a brief demo with Diamond production test pilot Rob Johnson. For anyone transitioning to twins, the L360 will be as good a trainer as any. Engine operation is unremarkable piston-engine standard stuff. Of course, where there used to be two levers in the diesel, there are now six for the DA42-L360.

We give Diamond high marks for making this forest of steam levers as unobtrusive as possible. The levers occupy a narrow console between the pilot seats and have no outward splay, so they don’t obstruct the view of the Garmin G1000. Fit and finish of the airplane we flew-inside and out-were typical of Diamond, which is to say first rate.

When we flew the Lycoming test article in Austria back-to-back against the diesel in 2005, we were impressed with its robust runway acceleration and sprightly climb. Thats still the case. The thing doesnt quite leap off the runway, but it leaves the diesel for dead. Initial climb is 1500 FPM and it will do 1000 FPM higher without breathing hard.

The diesels were fly by wire and silky smooth while the Lycomings have traditional cable controls. Theyre not quite as smooth to operate-especially the mixture knobs, which have locking levers and felt a little stiff to us. Some tweaking here would help. Rather than a simple percent power indicator, the L360 reverts to MAP, RPM and fuel flow, all displayed on the G1000. Cockpit sound level is moderately high-you can converse without a headset in a slightly raised voice.

Cruise is a little faster than the diesel, but not much faster. At 5500 feet, we noted 155 knots and 10.8 gallons per side, leaned rich of peak. The engines will run lean of peak, albeit with effort required to keep them smooth. Fuel flow drops to the low nines and speed to about 150 knots- a perfectly acceptable setting for training.

Single-engine performance is noticeably better than the diesel version which was, in our view, somewhat anemic. The Theilert-powered airplane will climb on one, but it takes precise handling and speed control. The L360 is more forgiving. Without trying too hard, Johnson coaxed a reliable 350 FPM climb from the right engine with the left caged. Of course, this requires the usual flurry of dead-foot-dead-engine-verify-secure to achieve, but thats why we have trainers, no? With the diesels, its all automatic.

Johnsons Vmc demo was a yawner. Vmc is a remarkably low 65 knots and pitching the airplane up to that value yielded an unenthusiastic, barely discernable roll

moment into the dead engine. Youd have to be brain dead to miss it.

Conclusion

So whats Diamond got here? Straight to the chase, it has a credible, aggressive response to the bag of hammers it got handed by Thielert. In a little over a year from Thielerts bankruptcy, Diamond has this airplane ready to sell and owners so inclined can convert. Although many DA42 owners are righteously steamed at having to spend so much to maintain their Thielert diesels and yet another pile of cash to convert to something better, we think Diamonds conversion pricing is realistic and reasonable and makes the best of a bad situation.

As for flyability, we might trade the Lycomings better performance for the diesels more leisurely but refined single-lever operation. Regardless of the Thielert engines show-stopping shortcomings, Diamond got the installation right and it proved that diesels can fly and that single-lever not only works, its a better way to fly, in our view.

Well reserve final judgment on comparing the L360 to Pipers Seminole. But were biased toward the L360 because its a modern airframe with better creature comforts, superior visibility and impressive single-engine performance, especially the benign Vmc demo. If potential Diamond customers don’t get flummoxed by having a choice of engines, Diamond will sell some L360s, especially in the fleet training market.

On the other hand, predicting whether this project will have legs is complicated by the fact that if the Austro engine pans out, we’ll bet that it will be the preferred powerplant, perhaps even in the U.S. we’ll know more in a couple of years. By then, Lycoming may have its IE engines available and the gasoline engine could actually become single-lever easy again.