Diamond’s DA40 is one of the more desirable used piston singles around. It works as a trainer, moves right along for traveling, and for those who might eventually step up to a Diamond twin, the DA40’s systems are a good primer.

But a big draw is the airplane’s sleek composite design and styling. If you like the looks of a Cirrus or Columbia, the DA40 will grab your eye. You’ll see a strong main structure mated with a long efficient wing born in the soaring world.

Like Cirrus models, you’ll pay a hefty premium for even the earliest DA40s. At press time in November 2021, we found damage-free and well-maintained models selling for double the suggested Aircraft Bluebook typical list price.

We’re told it’s worth the price of admission, where owner satisfaction and reliability are high. The DA40 has few bad habits, crisp and predictable handling, plus a familiar and reliable 180-HP Lycoming powerplant.

SAILPLANE DNA

Flash back to 1981 in Friesach, Austria, where Hoffmann Flugzeugbau began producing the H36 Dimona motorglider, a popular recreational airplane in Europe. Ten years later, Christian Dries and family took over Hoffmann and in 1992, it launched an effort at the North American market by opening a new plant in London, Ontario, in a converted World War II aircraft factory.

Diamond—then called Dimona—got its feet wet in the U.S. market by importing the Austrian-built DV20 Katana. In 1995, it began building Rotax-powered DA20-A1s in the London plant and selling these into what was then a lukewarm market for new trainers. By the time the company changed its name from Dimona to Diamond in 1996, it realized that both the North American and world markets had room for a composite four-place airplane.

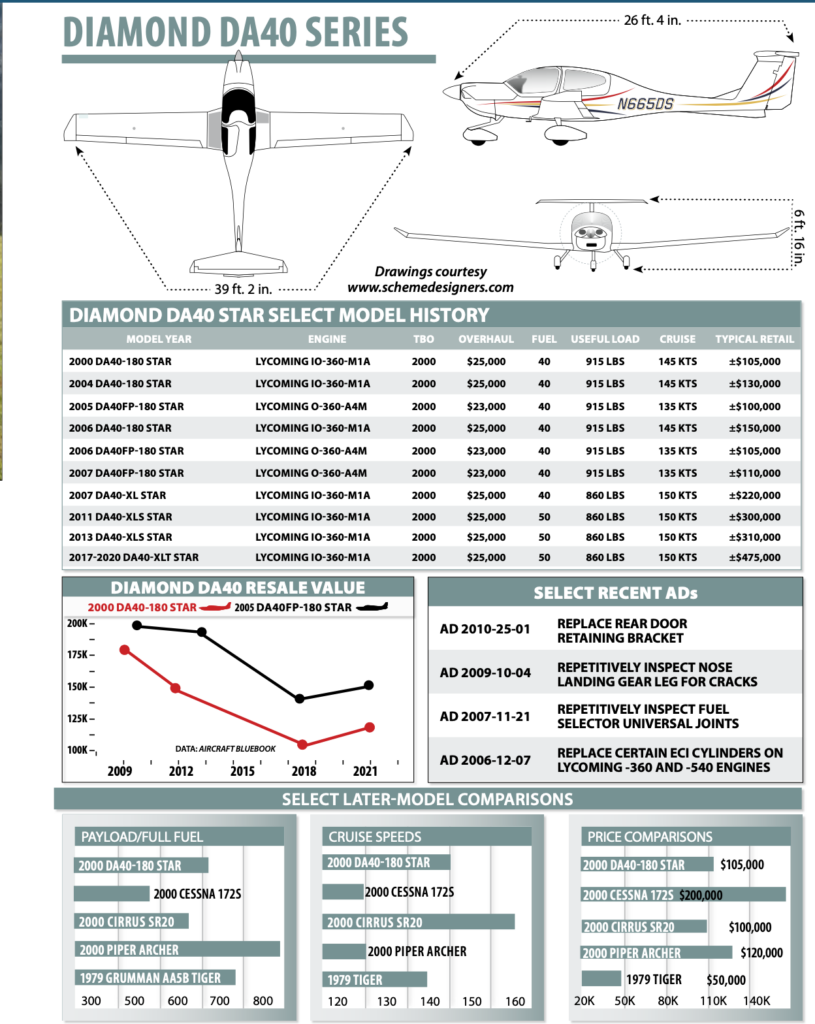

In 1997, Diamond announced the DA40 Diamond Star at the big European show in Friedrichshafen, Germany, with the prototypes powered by the Rotax 914 and Continental IO-240. But the airplane clearly needed more power. In 2000, the DA40-180 was certified with the reliable Lycoming IO-360 and a year later, production began in the London plant. Sales were initially brisk, especially to the trainer market which, increasingly, was turning to Cessna 172s for new training aircraft. Many flight schools found would-be students weren’t as price-sensitive as they once thought and wanted the option of two additional seats, which the Katana couldn’t provide. When it initially appeared in the 2000 model year, the DA40 sold for $189,900, typically equipped. Today (fall 2021), that 2000 model-year DA40-180 Star has an Aircraft Bluebook average retail value of $105,000—up nearly $30,000 from when we looked at the market three years ago. A 2011 DA40-XLS has a Bluebook average retail price of $300,000. To contrast, a 2011 Cirrus SR20 books at $230,000.

Initial deliveries of DA40s were equipped with dual Garmin GNS 430s and BendixKing KAP-140 autopilots. In 2004, Diamond announced that new Stars would have the Garmin G1000 integrated avionics system and that same year, Diamond announced a joint venture to sell and build DA40s for the Chinese market, primarily for training in that country’s burgeoning airline sector. Knowing it had found a niche, in 2005, Diamond announced the DA40-FP, a fixed pitch-only version of the airplane, with the carbureted Lycoming O-360. This model was aimed specifically at the training market. The FP’s base price at the time of introduction was $187,800.

In 2006, the DA40-XL appeared, which was basically just packaging of high-end options, such as the Garmin GFC 700 autopilot, Power Flow exhaust system, a composite three-blade MT prop, a 110-pound gross weight increase, electrically adjusted rudder pedals and a premium interior.

The airplane was clearly aimed at the upscale owner-flown market, which Cirrus was having good success serving. Fully equipped, the XL model sold for $329,000.

In late 2007, yet more versions of the DA40 appeared, the XLS and the CS. The XLS has a wider, higher canopy and a luxury interior while the CS is essentially an à la carte model with a constant-speed prop that lets flight schools configure it with interiors and other options. The base price of the CS was $259,950, while the XLS base was $334,950, or over $380,000 fully loaded. You’ll pay close to this in the current market.

CLEAN CONSTRUCTION

When Diamond bought Hoffmann, it paid attention to the company’s core expertise: building clean, strong glass structures. This is definitely reflected in the DA40’s construction, which was built along the same lines as the two-seat Katana/Evolution/Eclipse series.

The airplane fuselage is constructed of wet layup material in two halves that are bonded together longitudinally, with the vertical stab as part of the assembly. The T-tail is attached separately, as are the wings which, unlike the Cirrus aircraft, are two separate pieces joined at the fuselage center section. The wings themselves are laid up top and bottom in vacuum molds, then bonded together after the internals are installed.

We suggest reading the used composite airplane article in the April 2020 Aviation Consumer before buying. Repairs to composite models (including the paperwork chase) are quite different than metal ones, and many earlier DA40s have undergone major repairs.

The spar is a massive twin carbon-fiber spar layup between which the fuel is stored in removable aluminum cells. The fact that fuel is exceptionally we’ll protected may explain why Diamond aircraft have shown no tendency toward post-crash fires.

The cabin and cockpit is best thought of as a bathtub arrangement with a wraparound canopy in the front and a hinged rear hatch for the back-seat occupants. The canopy hinges at the front, rather than the rear, as on the DA20. The rear hatch is on the airplane’s left side and is equipped with a pin release for emergency egress. As with most of the modern composite aircraft, the DA40 has spring steel gear and a castering nosewheel, with steering via differential braking. The gear attach point loads are carried into the center section through attachments on the spar.

Unique among the big three composite lines—Cirrus, Columbia/Cessna (the TTx is gone, of course) and Diamond—the DA40 has center sticks with push-pull rods for elevator and ailerons and cables for the rudder. Rather than sliding seats, the DA40 has pedals that can be repositioned to adjust legroom. Trim is both electric and manual—there’s a trim rocker on the sticks and a center console wheel—and is activated by cables to an anti-servo tab on the horizontal stab.

ENGINES, SYSTEMS

Diamond kept it simple when it came to the powerplant: Lycoming’s 180-HP IO-360 has proven reliable and inexpensive to overhaul, at the expense of giving up some smoothness to six-cylinder Continentals. It’s also fairly light, an advantage in an airframe as light as the DA40. Gross weight in early models was 2535 pounds, while newer ones are 2645, compared to 2450 pounds for the Cessna 172 and 3050 pounds for the Cirrus SR22.

In 2014, Diamond brought the DA40-NG to market. Equipped with the 168-HP Austro AE300 diesel engine, the current Aircraft Bluebook shows a 2015 model retailing for $380,000. The engine has an 1800-hour TBO (time between overhaul) and a $30,000 typical overhaul cost.

Systems-wise, the Star has all the required new-age glitz. The aircraft fuel system has right/left/off settings, only one step down from the ideal off/on system for minimizing fuel-related accidents. However, as there have been no fuel-related accidents reported on Diamond Stars in the U.S., we’re hardly one to complain. The fuel selector is on the center console. One of the airplane’s operating limitations includes a requirement to keep the fuel load balanced.

As is the fashion, the DA40 is an all-electric airplane, with no vacuum system. It has a single battery, but also a single alternator, although there’s a battery backup for the electric gyros, and many now have retrofit glass with electronic backup.

One of the DA40’s strongest suits is the fabulous visibility afforded by the wraparound canopy; nothing else in GA comes close. But what plastic giveth, plastic taketh away. The cockpit can be boiling hot in the summer, although an opaque shade along the top of the plastic bubble tames some of the heat, plus Jet Shades (www.jet-shades.com) makes removable window shades, which can be kept in place during flight. Air conditioning is an aftermarket option in the DA40s. However, the canopy can be opened during taxi and is equipped with partial-open latches.

The heating and ventilation, once airborne, are good. In early models, the panel air vents emitted a noticeable and irritating howl, although some owners have found their own fixes for this.

PERFORMANCE, LOADING

When we reviewed the first production model DA40 in 2002, it blew away the competition, mainly the Cessna 172 and 172SP and the Piper Archer, both entry-level four-placers. Only the Grumman Tiger comes close in older designs, although the Cirrus SR20—also entry level—is faster by about 10 knots or so on 20 more horsepower. It easily kept up with the 200-HP Piper Arrow. The early Stars run around all day on 9.5 to 9.8 GPH at speeds up to about 140 knots. Subsequent models, say owners, are about 10 knots faster and, for the DA40-XLS, Diamond claims a 158-knot top speed with a 150-knot cruise on 10 GPH. Not bad.

With the Diamond DA40 Star’s long wing and relatively high aspect ratio, the Star is a terrific climber, even when loaded. Moreover, it leads the league in short-field capability, easily hopping off the runway in 1200 feet or less with a heavy load. At 2535 pounds (2645 for newer models) gross, the Star is light; at 14 pounds per HP, its power loading puts it in the middle of its class. (The Cirrus has power loading of 15.25 lbs/HP, while the Cessna 172 is lower, at 13.6 lbs/HP.) Nonetheless, any competent pilot should be able to comfortably operate a Star out of 2000-foot runways, at reasonable density altitudes.

Payload-wise, the Star is really a three-place airplane with baggage space, even at the higher gross weights. Useful loads are in the 850-pound range, although some owners report less.

So with the tanks full, it can carry about 600 pounds—three people with some bags. There’s a 10-gallon extended-range fuel tank option that reduces cabin load.

In early Stars, the baggage compartment was a bit of an afterthought, accessible only through the cabin by tilting the rear seats forward. The area itself was quite shallow. This was later redesigned, and now the rear seats fold forward to essentially turn the back seat into one huge baggage bay.

The Star’s weight-and-balance envelope is relatively benign, narrowing a bit toward the gross weight limit. Early models tend toward forward rather than aft CG. Offloading fuel is always an option to stuff in more payload, but the airplane carries only 40 gallons usable to begin with, so its range is hardly exceptional. The 10-gallon extended range option helps, but owners complain it narrows the CG envelope, something that needs watching. The newer XLS models come with 50-gallon tanks as standard.

HANDLING, ERGOS

Entering the Star’s cockpit requires hiking up onto the wing and stepping down into the we’ll of the cabin. It’s a bit of a practiced art, requiring gripping the canopy’s tubular hinges to gain purchase, both for ingress and egress. Not easy, perhaps, but you get used to it.

The rear-seat passengers simply step through the hatch and into the rear cabin, which is quite spacious. (Watch the opened rear hatch, though—it’s just the right height to bonk an unwary head.)

The front seats don’t slide fore-and-aft, but the rudder pedals adjust. A 6-foot-5-inch owner reported that, while a little cramped, the pilot’s seat has adequate room for him. Rear-seat passengers enjoy adequate footroom, thanks to footwells. With the adjustable rudder sets, the front seats have good legroom for such a small aircraft. As noted, cockpit visibility is nothing short of fabulous—the best of any GA airplane, other than the Katana/Evolution/Eclipse series.

Of all the GA airplanes we’ve flown and tested, the Star ranks at the top as being the most fun to fly. It’s not quite as we’ll balanced as a Bonanza, but it has no bad habits, and pitch and roll forces are light and easy to manage with the stick. Slow flight and stalls are non-events and even deep into the stall, the airplane simply mushes and could probably touch down that way in a survivable impact. Airplane flaps have little or no effect on trim condition, but neither are they as effective as the barn doors on a Cessna 172.

Landing a Star isn’t particularly difficult, but the sight picture over the nose requires some acclimation to avoid too-high flares. Flown into the flare faster than about 65 knots, the Star will float, so slower is better.

We’ve long been impressed with the safety record of the Diamond DA40 series and can’t help but wonder if they don’t have secret anti-gravity devices installed at the factory—they rarely crash.

For our accident scan our practice is to look back as far as necessary to get the 100 most recent accidents for the type. No such luck with the DA40 series—there are not even close to 100 reported accidents since the type went into service in the year 2000.

We think that there have been 23 DA40 accidents in the U.S. We say that without certainty because we have clear evidence that since the NTSB introduced its new search engine “CAROL” a year ago it is no longer possible to find all of the NTSB accident reports for a type of aircraft. When we searched for DA40 accidents in 2017 we found 18. When we searched for this review we found a total of 16—and five of those occurred since 2017. We have contacted the NTSB asking what the devil is going on with access to accident data. We’ll let you know what we hear—we think the inability to access accident data is a safety of flight issue.

By using current data and that we saved from 2017, we are confident that the number 23 for total U.S. accidents is reasonably accurate.

We saw nothing in the accident reports we read to indicate there is an issue with the design or manufacture of the DA40 series. Looking at what we expect to see as the most common cause of accidents for any airplane, runway loss of control (RLOC), we saw only two for the DA40. That’s low and consistent with our experience flying the marque—good ground handling and the ability to deal with significant crosswinds.

There were only two engine stoppage accidents. The cause was listed as unknown on one. With this we reiterate our call to the NTSB to stop wasting its time investigating inadvertent gear-up landings because nobody has been hurt in one in decades and put more effort into finding engine power loss causes because those accidents kill people.

We think of the DA40 as a decent short-field machine; however, it will not levitate and the POH numbers have to be respected. One optimist tried to take off uphill on a grass runway with four aboard. The POH said the airplane would need 1570 feet to clear an obstruction. Unfortunately, only 1150 feet were available and the airplane hit the tops of the trees.

Two pilots tried to proceed VFR into IMC without notable success. One pilot managed to spin a DA40 into the ground from enough altitude to develop a steady 6000-FPM descent. We can’t help but wonder if that was a suicide. We contrast that with a DA40 that picked up such a load of ice on an instrument descent that it stalled at 1000 feet AGL. In a tribute to the crashworthiness of the airplane as we’ll as its benign handling, all aboard survived the ensuing ground impact.

The sacred and foolish aviation tradition of descending below minimums in hopes of spotting something on a instrument approach was continued by only one DA40 pilot.

One DA40 driver called a friend on a boat and asked that the friend shine a light so that the pilot could see the boat as dusk approached. The pilot then made a series of low passes at the boat that continued until he hit the water.

We want to highlight the excellent crashworthiness of the DA40 series. We found no evidence of any post-crash fires—something we think is unprecedented. We were also impressed that a DA40 protected its four occupants when its pilot stalled it into trees following a decision fly low to search for elk in a blind canyon.

MAINTENANCE, MODS

The Lycoming IO-360 is one of the most reliable four-cylinder powerplants available; we heard no complaints from owners about it, save for a few owners who had problems with electric fuel pumps.

Some owners complained of early teething problems with the Garmin G1000. We still hear plenty of complaints about Garmin and Diamond being slow to produce software upgrades for non-WAAS aircraft. The early Star’s weak landing lights are a point of contention. We found only a handful of ADs against the airplane, one requiring replacement of the rear hatch retaining bracket, one requiring inspection of the nosegear pivot axle, one requiring inspection of the universal joint on the fuel switch and the last requiring a one-time fuel system inspection.

As for aftermarket mods, there are some. One popular one sold through Diamond dealers is the Cabin Cool air conditioning system. There’s also the PowerPlus standby alternator system and a stylish and functional interior upgrade package.

There’s also a custom exterior striping package, plus for better climb and a couple extra knots in cruise, a Hartzell ASC composite propeller is available.

There’s the Forced Aeromotive supercharging mod (www.forced-aeromotive.com), and we looked at aftermarket supercharging in the May 2020 Aviation Consumer. The kit for the Diamond is roughly $30,000. The mod is not for everyone, as we discovered in a follow-up article focused on the DA40 application in the August 2020 Aviation Consumer.

OWNER COMMENTS

I am the second owner of a 2002 DA40, purchasing it in 2012 (but having flown it regularly since 2008). It has its original six-pack panel. It truly was love at first flight: responsive, efficient and amazing visibility, with a remarkably low accident rate.

N440JP includes a GNS 430/530, upgraded to WAAS shortly after purchase, as part of adding the Garmin GDL 88 for ADS-B compliance. The autopilot is the original KAP-140 two-axis system with altitude preselect. Additions over the following years included the max takeoff weight upgrade, Power Flow tuned exhaust, SureFly electronic ignition system and Forced Aeromotive belt-driven supercharger. Two years ago I decided to replace the original (3300 hours) Lycoming IO-360-M1A with a factory remanufactured zero-time engine of identical type.

Equipped as noted, the plane handles high-density airports with ease (the supercharger boosts manifold pressure by 7” so the engine develops full sea level power at up to 7000 MSL). Climbing into the low to mid-teens with a passenger plus baggage is the go-to option for long cross-country flights, when weather and winds aloft permit. My strong preference is for lean-of-peak operation to save fuel, extend range and avoid intermediate fuel stops. For example, a recent 500-NM trip at 15,500 feet MSL took 3.45 hours (negligible winds aloft). Using a 7-GPH mixture setting (LOP), the trip consumed 30 of the 40 gallons available, leaving about a 90-minute reserve on landing. Cruise flight at that altitude running LOP yielded 138 knots true. For those who like to go faster and burn more fuel, a ROP 10-GPH mixture setting in the same scenario yields about 150 knots, but this is hardly a good tradeoff for a 50 percent higher fuel bill!

Fixed annual costs are $1000 in taxes, $2400 in insurance, $600 for databases, $1200 for three oil changes, $4300 sheltered tiedown and $1200 for monthly washes. Annual inspections fluctuate, but plan on at least $6000. The only true operating cost is fuel (my oil consumption is negligible). For long cross-country flights, I flight plan for 8 GPH overall (this takes into account the higher burn rate during climb, 7 GPH during cruise and lower burn rate during descent). With avgas now running about $5 per gallon, this translates to about $40 per hour for fuel. I fly about 100 hours annually, so my total annual fuel expense is about $4000.

The DA40 turned out to be we’ll suited to my needs (mostly long cross-country flights either solo or with one passenger). Its long-term safety record is paramount for me. I believe that record comes from Diamond starting with a clean-sheet design that emphasized safety. It has benign stall characteristics, with excellent crosswind handling ability. And it has great ramp appeal.

Robert Bernstein – via email

I purchased a 1700-hour, 2003 DA40 in 2019. The older DA40s are an excellent value considering they are all-electric, composite, low wing, cruise at 140 knots and are Lycoming powered. Mine has a GNS 530W/430W pair, an HSI, a KAP-140 autopilot, a digital engine monitor and a leather interior. Right away I added a Garmin GTX 345 ADS-B transponder.

The center stick is fun and took about one minute to get used to, and doesn’t block the view of the panel like a yoke. Takeoffs and landings are easy, but the landing attitude is relatively flat, so it can balloon. Adding full power and retracting flaps for a go-around causes no appreciable pitch change. I usually fly at 6000 to 7000 feet at 65 percent power (economy) burning 7.6 GPH at 130 knots true. Top speed is 140 knots true at 11 GPH. My DA40 has the 40-gallon tanks, which is enough. The weight and balance is improved over the 50-gallon planes, which are less prevalent in the older fleet. The aluminum tanks are protected by fore and aft spars and connected to the fuselage by flexible hoses for safety. Fuel tank maintenance is infrequently required, but expensive, because the wings are removed for access. My full-fuel payload is 603 pounds, which is all I need for one to three people, plus some luggage.

I like the reclined front seats, and with sheepskin covers they are very comfortable. I recently added Oregon Aero (www.oregonaero.com) seat cushions and now the seats are perfect. I’m 6-foot 3-inches and I have plenty of legroom, although on longer flights I miss the leg stretch I could get in something like a Skylane. For longer flights, the autopilot is a welcome feature. The KAP-140 has altitude preselect, and can fly ILS and LPV approaches, if it isn’t too windy. I don’t have GPSS but it can be added. The wraparound canopy and narrow wings make every flight like an IMAX movie. In the spring, fall and winter the greenhouse effect from the canopy helps to keep the cabin comfortable. In the summer, it can get a little warm on the ground and at low altitudes, but it’s a short season in Minnesota, so for me that’s not a problem. The heater is not great, but I’ve heard that adding a Power Flow exhaust helps. The back seats have the most legroom, and a great view. Behind the back seats is a small luggage compartment and a ski tube extending into the tail.

On the ground, loading is aided by a rear door, which is also a safety feature. In an emergency, the hinges can be removed from the inside with a red handle to get out. On hot days, I can taxi with the front canopy open about an inch (but still locked) for cooling. The free-castering nosewheel took about one flight to get used to, and it allows me to turn on a dime. The 39-foot-2-inch wingspan isn’t a problem for my FBO’s hangar, but it might be tight for private hangars.

I’ve been through three annual inspections (my plane has 1900 total hours), with no significant problems found. The cost ranged from $1600 to $2500. Maintenance costs for the first three years of ownership were $2000 to $3000 per year, plus the cost of a prop overhaul this year. Outside of the annuals I’ve replaced the Dukes electric fuel pump with a Weldon, which most owners favor, the main tires and the altimeter.

The Lycoming IO-360 is an economical and reliable engine that usually makes it to TBO without much trouble. I have three ADs on my plane. The Lycoming fuel injector lines are inspected every 100 hours. The nosegear is inspected every 200 hours for cracks. The aft main spars require reinforcement before 2000 hours. There are also reports of some planes developing corrosion involving the metal imbedded in the wings for lightning protection. That requires grinding down the composite, making the repair and then rebuilding—so it’s expensive. My mechanic is comfortable with my plane and services a DA20. This year I signed up for the SavvyQA service, so I also have a Diamond mechanic in California that I communicate with. The diamondaviators.net user group is a tremendous resource for owners and pilots, but you do read about all the various mechanical problems that can occur with the plane. My insurance was $1130 this year.

Numerous DA40 upgrades are available including propellers, Power Flow exhaust, an extended baggage area, a gross weight increase, a wider canopy, speed mods for the landing gear, LED lights, a larger rudder, electronic ignition and avionics. Early airplanes are limited to the rate-based KAP-140 autopilot. It’s not a bad autopilot, and it’s fully supported, but I’m hopeful for a digital option in the future. The Vision Microsystems digital engine monitor/engine gauges/fuel gauges and totalizer is no longer in production and gets only limited support from JPI, so a new engine monitor is in my future. There are DA40 STCs for the EI and JPI monitors. I might also get the LED lights. The original ones are a little dim.

If you want a pre-G1000 DA40 start looking now. They don’t come up for sale very often, especially in the Midwest. I think the secret that these are great planes is out.

John Mullen – Minneapolis, Minnesota

I have owned a DA40 since purchasing it new in 2002. It was one of the very first (serial #40.208) produced by the London, Ontario, plant. I think of it as a second-gen DA40, as the panel and various options were changed from the pre-2002 models. It came with GNS 530/430 navigators, KAP-140 autopilot and a KCS55A HSI. Early models tend to be considerably lighter and have a more forward CG than later ones. They also are somewhat slower in cruise.

Given the limitations of the GNS units, the iPad/ForeFlight/Stratus combination is pretty much indispensable, plus I’ve found a way to conveniently mount an iPad Pro 11.

Having installed the MTOW/MLW mod and the original 40-gallon tanks, I have a 947-pound useful load and full-fuel cabin loading of 707 pounds. To get it out of CG, I almost have to do it on purpose.

The plane cruises considerably faster than it did originally, mostly thanks to the Power Flow exhaust. At useful cruising altitudes (10,000- to 12,000-foot density altitude) it’s about 11 knots faster than book, whereas it used to be right on book. Generally I’ll file 140 knots and I’ll be a bit above that in calm air. It also considerably outperforms book figures (and original actual performance) in terms of takeoff and climb.

Given that it has the ubiquitous Lycoming IO-360, pretty much everything in the engine compartment should be totally familiar to any experienced mechanic in the U.S. Various parts that may be needed are easily obtained. This is also true of the Cleveland wheels and brakes, which of course are wear items. The only real wrinkle is that the engine is mounted close to the firewall, so certain things require a bit of agility to accomplish.

Some various challenges over the years include the original quartz-halogen landing lights. They were replaced with far superior XEVision 35W units. These days LED replacements are available and in vogue. The MT prop gave me a problem in 2009 that resulted in a 100-day downtime due to less-than-stellar support from MT at that time. However, I had a factory overhaul/exchange done in 2015 that went very we’ll and the prop has been completely trouble-free ever since. I installed a SureFly SIM and the original release was not all that happy in some 28-volt systems (not unique to Diamond). SureFly provided a power conditioning solution that worked OK. There is now a rev D that inherently corrects the original problem in the unit itself. It was just installed (and the external corrective gizmos removed) recently and it is running great.

One rare thing that Diamond does is put all publications (maintenance manuals, POH, service bulletins) readily available to anyone on its website. There is also an online interactive parts catalog that is somewhat helpful, but not we’ll maintained so there are a lot of omissions. The diamondaviators.net forum is a wealth of shared experience and advice for all things Diamond and functions very we’ll in lieu of a formal owners’ group.

Rich Doyle – via email