Pop

At the time,

Aviation Consumers report could best be described as modestly impressed but skeptical. “If Cirrus delivers on that price,” we opined, “and survives the certification gauntlet-were skeptical on both counts-the SR20 could be a hot seller.”

We were wrong about the certification but right on the price and sales appeal. Adjusted for inflation, $130,000 is $165,000 today and a new SR20 invoices for closer to $250,000, a total that hasnt, nonetheless, given qualified buyers much pause. Glass panels as standard equipment-something we didnt foresee in 1994-have broadened the Cirrus sales appeal.

Cirrus promised that its all-composite airframe would suppress production costs and with a plastic instead of metal structure, the airplane would be more durable and easier to maintain than aluminum airplanes. But 12 years into the project- seven for production models-have those claims been borne out? How have the airplanes fared in the rough-and-tumble real world? As the old Buick ads used to say, we decided to ask the man who owns one.

Target Market

The first four Cirri were test aircraft and Pepple bought his airplane, N415WM, from its original owner, Walt Conley, about three years ago, after owning first a Piper Cherokee and then an F-model Mooney. “This one [the SR20] Ive by far flown the most,” Pepple told us.

The Klapmeiers never miss an opportunity to stress that their goal wasnt just to sell airplanes, although they have-number 3000 will be on the assembly line sometime in November. They continue to pitch the notion that general aviation needed an attitude adjustment and that flying must be accessible and relevant to a broader range of people. With its simple systems and the CAPs ballistic parachute, the SR20 was supposed to do that.

But did the very idea of an accessible airplane draw Pepple into aviation? Not really. The SR20 is his third airplane and he told us he would fly whether the Cirrus existed or not. Still, Pepple, whose business sells and maintains hundreds of ATMs in the Northwest, is a poster child for the Klapmeier mantra of creating and maintaining value in not just flying but the entire GA experience. “I do travel a ton on business,” he said. “I can jump into the airplane and take a 32-minute flight to see a customer instead of taking a four-hour drive. It comes in really handy.”

But a Bonanza or a Mooney can do that, too. At this juncture, the Klapmeiers shrewd understanding that the decision to fly is not entirely objective nor necessarily singular intervenes. “We were looking at an A36 Bonanza and those are great airplanes,” Pepple recalls. “Then my wife said, Does it have a parachute?”

Domestic concerns notwithstanding, Pepple finds a degree of comfort in that big handle on the ceiling since much of his flying is over mountainous areas with few options for emergency landings. Weve heard the same from other Cirrus owners.

Diurability

“Its just like any other airplane,” says Hudnall. “They (Cirrus) had a lot of little problems at first, which is to be expected, but theyve been really good about addressing those problems.”

In N415WMs maintenance log, we counted at least 21 service bulletin notations and at least three airworthiness directives that have been complied with. There have been seven ADs issued for SR20s, but not all models were affected by all of them. The service bulletins were scattered relatively evenly through the maintenance history and involved mainly inspections where, in most cases, no fault was found, small part replacements or small modifications to assemblies. “Its been all minor stuff, cosmetic mostly,” says Hudnall.

As youd expect, the ADs were more serious. One required substantial re-rigging of the parachute activation system, another the replacement of the roll and yaw trim cartridge and both were issued in 2002. An AD issued in 2005 required modifications to the crew

seat recline mechanisms to prevent the seats from folding forward in an emergency landing. The only serious problem Hudnall has encountered in multiple aircraft is one he believes is pilot-induced. “If there was one weak spot, its the brakes,” he says. “But if you operate the airplane within its limits, its fine.”

According to the FAA, there have been four brake fires and two incidents of loss of directional control in Cirruses due to brake overheating problems. Last May, the agency issued a Notice of Proposed Rulemaking, which, if adopted, would require replacement of caliper piston O-rings and possibly the replacement of caliper assemblies.

It would also require the application of heat-indicating stickers on the brake parts that change color if the brakes have been overheated and make it a requirement to include a check of the stickers (through newly-drilled holes in the wheel pants) during every preflight.

In the brake fire incidents, the brake temperatures reached the point where the O-rings failed and allowed brake fluid to drip on the red-hot brakes where it ignited, in some cases causing serious damage to the aircraft. At this writing, the NPRM has not been adopted as a final rule, but its likely to be. In the meantime, Hudnalls advice to pilots, not just Cirrus pilots, is simple: don’t ride the brakes. He says the worst example of brake abuse hes seen on a Cirrus was a set of pads that had been worn not only through the pad material, but also through the rivets that secure the material to the metal backing. The owner complained that the brakes were “getting a little soft.” Hudnall says pilots routinely set power too high for taxiing and apply constant braking to slow the airplane when all that should be required from the braking system during taxi is the occasional tap to maintain directional control.

CosmeticsAircraft condition is usually a reflection of not only the quality of maintenance, but the TLC of the owner. Its clear that N415WM has been doted over. The interior is all but spotless, the glass clean and the leading edges and cowl rubbed free of bugs. Pepples proud of the way his airplane looks, enough so that he removed some factory-applied pin striping that he thought detracted from the airplanes lines.

“I like it clean and simple,” he said. Pepple changes the oil himself and the airplane is always in a spacious, nicely appointed hangar when its not in the air.

Wear and tear is inevitable, however, and N415WM has a few age spots. A small crack has appeared in the finish of the leading edge of the right horizontal stabilizer. Hudnall was concerned enough that he sent photos to Cirrus for assessment. He was assured that the crack is a surface flaw and not a delamination of the composite material.

“Its just a cosmetic thing,” Hudnall says. His paint technician will sand out the crack and repaint the area. We found a couple of dime-sized chips in the paint (cowl and wing leading edge) and a few that have been touched up.

Interiors have been a weak spot in earlier model Cirruses and Pepples has had three headliners. The original cloth seats were replaced with leather at 99 hours. There’s now noticeable wear on the pilots armrest, and to some extent, the front passengers as well. Its something Pepple plans to address soon.

As for maintenance snags peculiar to this airplane, Pepples done his share to support the aviation economy. Hes recently replaced the GPS antenna, the alternator and the Garmin GNS430. Charging system problems were eventually traced to electrical arcing from a landing light connection. He says a base annual costs about $2000.

And, although Pepple wasnt having any problems with it, earlier this year, Cirrus asked to replace the airplanes nose gear strut. Apparently some aircraft have had problems with the strut retention nut and Cirrus wanted the strut for comparison. Cirrus covered the entire cost.

By far, the most vexing problem to plague this aircraft happened long before Pepple bought it from Conley. Conley was on a night IFR flight in November of 1999 (111.7 hours on the aircraft) when the engine-driven vacuum pump failed. As part of the certification, the FAA required a backup electric pump and it engaged automatically. Conley was able to continue to his destination with the vacuum pump idiot light gleaming from the panel.

It was a sight he was going to get used to. The second pump failed the following February with only 75 hours on it. A third cratered just 46 hours later. In all, Cirrus paid for the replacement of seven pumps in 17 months. An attitude indicator and two directional gyros were also replaced. Finally, Conley, Cirrus and engine maker Continental agreed it was time for drastic action. With Conley paying a prorated amount for the 450 hours that had accumulated on the engine, Cirrus and TCM replaced the entire engine with one out of the box.

“Continental wanted to take it apart and see if there was something in the engine that was causing vibration or something to make those pumps fail,” Conley said. “I don’t think they found anything.”

Nor has he heard of similar problems in other early-model Cirruses. However, Conley thinks that rather than yanking the engine, a simpler solution may have been right under their noses. The original engine had an Airborne vacuum pump and the new one has a Sigma-Tek, which is humming along trouble-free to this day. A starter drive was replaced at 350 hours on the old engine and the new engine needed the number four cylinder overhauled after about 400 hours. Today, its running strongly with leak-down compression values consistently in the low 70s.

Conley picked Cirrus to replace his Grumman Tiger not because of the parachute, the performance or the technology. “It was the only airplane that I fit,” said Conley, whos 6-feet-4 inches and weighs more than 200 pounds. When he put down his deposit, he was about number 100 in line, but through some deal making, he was able to get the number two position held by Cirruss accountant. When the customer holding the first position (the company lawyer) backed out, it was Conley who accepted the keys in a splashy media event.

As a first customer, Conley didnt disappoint Cirrus. He embarked on a circumnavigation of the continental U.S. from Minnesota to his new retirement home in California, enthusiastically (and patiently) answering questions from pilots, FBO staff and even air traffic controllers as he wended his way to California. He kept an online journal of his travels (before they were called blogs) in which he listed performance data and described in detail the flight experience and, in general, painted a glowing picture of the aircraft, which many were skeptical of at the time, if theyd heard of it at all. “I cant tell you how many times people asked me Whats a Cirrus?” he said.

Conley remained a staunch booster of the airplane and Cirrus made him its sales rep for Northern California and Nevada in 2003. Not long after that, Pepple called him and Conley flew to Medford with a new demo airplane. Pepple said he was ready to buy a new SR22, but the deal didnt go through because of a dispute in the contract wording. Pepple said he made changes to the contract that he believed reflected his understanding of the verbal agreement that had been reached to trade in his Mooney, but Cirrus wouldnt accept the changes and returned the contract to him unsigned.

“It soured me on the company, but it didnt sour me on the airplane,” he said. Meanwhile Conley was racking up the hours on company demos while N415WM sat idle most of the time. A deal was cut and Pepple took delivery in late 2003.

PerformancePepple is less enthusiastic about the performance of the airplane. For one thing, while Conley insists the airplane cruised at 160 knots true, Pepple says it doesnt. “I get 147 knots,” he said.

Flight conditions where Pepple usually goes are also different than many. Medford lies in an inland valley about 60 miles from the coast. Summer temperatures routinely hit triple digits, significantly raising the density altitude from the airport elevation of 1300 feet.

“Any direction you go, you have to clear 5500 feet,” he said. Some of his summer destinations are higher than 4000 feet and on a hot day, they stretch the SR20 to Pepples limits. Although hes IFR-rated, Pepple says he rarely flies in IMC because of the performance limitations of the airplane as they relate to his own limits as a pilot.

“Im a conservative pilot and Im not saying Im pushing the airplane to its limits, but I am pushing it to my limits,” he said. On a recent trip to Reno, on a solo flight with half tanks, he felt he needed a 360-degree turn in the climbout to reach a safe altitude.

“And thats in a 200-horsepower airplane,” he said. Hes especially cautious when all the seats are full for a family trip to the beach. “You have to plan for it. If I know I have to fly, I plan to fly in the morning,” he said. In general, however, the airplane gets him where he needs to go when he needs to go there. “With two people and half tanks, I can go anywhere anytime,” he said.

Whats next for Pepple? Probably an SR22. He wants the extra horsepower and the confidence it brings. He says hed fly on instruments more and likely get even more use out of the 310-horsepower model, both for business and pleasure.

ConclusionOn our largely subjective scorecard, how we’ll has Cirrus delivered on promises it made in 1994? Fairly well, in our estimation. The SR20 isn’t the 160-knot airplane they promised-Cirrus has since scaled back speed claims-but it has proven to have no ugly warts.

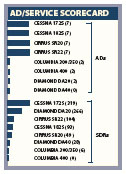

The number of ADs, service bulletins and service difficulty reports (49) is surprisingly low for a clean-sheet airplane and none are major worries. With seven ADs and more than 300 SDRs, Cessnas re-heated 172S hasnt done quite as we’ll as the SR20 in this regard. On the other hand, Diamonds DA40 Star, also a clean sheet design, has no ADs at all.

Maintenance-wise, the SR20 so far seems to be about average. It appears to represent no major breakthroughs in either long-term durability or reliability. Clearly, it doesnt corrode. But the composite surfaces get dinged and need repair. Cirrus interiors, at least the early ones, appear to wear no better than those in other aircraft, regardless of vintage. Some owners have complained about cheesy knobs and fit and finish details. New airplanes seemed to have improved this.

And what of the parachute? To date, we count nine Cirrus CAPS deployments. All of the occupants survived, although there were some minor injuries. In one case, early in the SR20s history, the occupants tried and failed to deploy the CAPS, but still survived. In another, the pilot may have deployed outside the CAPs speed envelope and did not survive.

There’s little doubt that the CAPS appeal has been instrumental in the sales success of Cirrus airplanes and even skeptics will probably concede that deployment outcomes have been far rosier than Cirrus ever promised. In the September 2006 issue, we reported that several CAPS save involved loss of control that likely would have been fatal otherwise. In that sense, the CAPS has measurably reduced the Cirrus fatal accident rate.

Russ Niles is a news editor at

Aviation Consumers sister publication, www.avweb.com. He lives in British Columbia.