Every pilot who’s ever packed an airplane for a trip has experienced the desire for more—more room, more useful load, more seats, more. . . As a family grows, the four-seater isn’t enough—the baggage kids seem to need grows exponentially with age. Part 135 operators want a small freighter that is rugged and can get in and out of remote village airstrips with a big payload.

Airplane design is tough—optimizing for speed hurts payload; a large comfortable cabin may mean stodgy performance and no baggage capability. Rumor has it that trying to find an optimum compromise between speed, payload, range and comfort has driven more than one aeronautical engineer around the bend. Many airplanes that have been advertised as “do it all” machines aren’t.

Perhaps the poster-child exception is an airplane such as the Cessna 206 Stationair, which carries the SUV/minivan/pickup concept to a capable conclusion.

It’s not fast, nor is it that slow, but it is stable, rugged, reliable, has six real seats and is remarkable for being able to carry a half-ton or so after the tanks are filled. You can put it on floats, turbocharge it, dump skydivers from it, and carry small packages or just your family. It has proven tough and reliable enough to be a fixture in the bush throughout the world, holding on even as turbines shoulder out piston power.

So popular has been the 206’s combination of simplicity and load-carrying that it’s one of three singles Cessna saw fit to bring back to the land of the living when it restarted piston production. As a result and in addition to a wide range of mid-1960s and later airframes on the market, one can also opt for a brand-new one.

Stationair History

Cessna’s biggest fixed-gear piston single is really three models, though all are essentially the same airframe. It was originally introduced in 1963 as the 205, a fixed-gear 210, technically known as the 210-5. It had two doors up front and a relatively small rear door on the left side. The engine was a 260-HP Continental IO-470. This airplane was a fixed-gear version of the recently revamped 210; it was produced for two years, with 577 delivered.

In 1964, Cessna responded to demand for more utility and created the U206 (U for “utility”) Super Skywagon, with a 285-HP Continental IO-520A, redesigned wing and bigger flaps. Intended as a flying pickup truck, even the seats were optional. There was one door for the pilot and a big double door aft on the right side.

The next model year saw the 205 become the P206 Super Skylane, with “P” representing “personal” or “passenger,” depending on with whom you’re speaking. The P206 had the same door arrangement as the 205, but with the bigger engine from the 206. The U206 was by far the more popular of the two.

In 1967, the U model got a takeoff-weight boost and a new engine, the 300-HP Continental IO-520-F,

while the P model kept the 285-HP O-520-A. Turbocharging became available on both variants in 1966, with a 285-HP Continental TSIO-520C. The P206 was discontinued in 1970, with a total production run of 647. The remaining U206 and TU206 were offered with either a utility or passenger interior, and renamed Stationair.

A stretch of the fuselage brought into being the 207 Skywagon in 1969, powered by the 300-HP IO-520-F. One more seat was added, bringing the number available to seven. Useful load went up by about 30 pounds. An additional bonus was a nose baggage compartment, easing the task of getting the CG in the proper place during loading. The turbo model of the 207 was powered by a TSIO-520-G, also with 300 HP.

Camber-lift wings, which feature a slightly cuffed leading edge, were added in 1972. These improved low-speed handling at almost no cost to cruise speeds. At the same time, the baggage compartment got a 7-inch stretch. An aerodynamic cleanup in 1975 boosted cruise speed by about 6 mph. The cleanup included more-streamlined wheel pants and improved cowl flaps.

In 1977, the horsepower of the turbo engine was upped to 310 (for takeoff only) on both the TU206 and the T207. A wet-wing fuel system was introduced in 1979.

In 1980, another seat was added to the back row of the 207, making it an eight-place airplane. This created the Stationair 8, but the Cessna designator remained model 207. The world would have to wait for the Caravan to see a model 208 and what may be the ultimate evolution of the high-wing, strut-braced single. The 207 was discontinued in 1984, and the 206 two years later.

It was a great run. Along the way, 206s saw several suffixes added, starting with the 206A in 1966 and culminating, temporarily, with the 206G in 1986. More than 7000, by serial number, U206s had entered the market, along with 647 P206s, the 577 aforementioned 205s and another 788 207s.

But then a funny thing happened: In the mid 1990s, Cessna started making piston-powered airplanes again. After starting up assembly lines for the 172 and 182, the model 206 returned in 1998 as the 206H, powered not by a Continental IO-520 but by a 300-HP Lycoming IO-540-AC1A. It was joined by the T206H, powered by a 310-HP Lycoming TIO-540-AJ1A. Cessna recently stopped production of the normally aspirated 206 but has kept going with the T206H and is selling them for we’ll north of $600,000. Unlike the Continental-powered 206s, the H model is available with a five-place, club-seating option.

Cessna Marketplace

Enormous fixed-gear singles aren’t all that common in the marketplace. In terms of mainstream aircraft, the choices are pretty much limited to the Cessnas and Piper PA-32 Cherokee Six/Saratoga. Prices are comparable, and which makes the better choice depends in part on your needs. The big Pipers have a wing spar running through the cabin right behind the front seats, disrupting the loading area somewhat, and the Cessna is definitely the airplane of choice for floats. Both companies’ products have proven reasonably reliable over the years.

The Pipers do have an edge in TBO over the Continental-powered 206s. While the best one can hope for from the Continental-powered Stationairs is a 1700-hour TBO, the Lycoming-engined 206s have TBOs of 2000 hours.

The -540-series Lycomings bolted on the Pipers have a TBO of 1800 hours (for the TIO-540-S1AD), and as much as 2000 hours in the case of the IO-540-K1G5 on the Saratoga and the Cherokee Six.

Loading

This is the name of the game for Stationair pilots. While no airplane can handle anything you can fit in it, the Stationair comes closer than most. Full-fuel payloads of 1000 pounds or better are not at all uncommon.

The big rear cargo doors—creating an opening more than 44 inches wide—make getting bulky cargoes inside less of a chore than in other aircraft. Another nice touch is the lack of a lip at the doors, so cargoes don’t have to be maneuvered up and over to get them inside.

The airplane can be flown with the cargo doors off which, combined with solid low-speed handling, makes it popular with aerial photographers and public benefit flying organizations involved in conservation research and monitoring. Public benefit flying organizations LightHawk and CAVU have owned multiple 206s, using them in remote areas.

Specialty kits were made available so the Stationair could take on such jobs as glider towing, parachute jumping and even aerial hearse service. There also is a cargo pod available. When using a cargo pod, make sure you follow any limitations on flap deflection that are on the STC for the installation.

With or without the cargo pod, the Stationairs offer ample loading flexibility. The allowable CG range is unusually long, making cargo/passenger positioning less of a juggling act than with many aircraft. However, despite some pilots’ assertions that “If you can get it in, you can take off,” weight and balance computations are not optional. Several accidents over the years show it is possible to load a Stationair outside its envelope.

Comfort

While the Stationairs have large cabins, they’re not long on comfort with a full load of passengers. Noise levels, particularly during takeoff and climb, can be fairly high as piston-engined singles go. And the rear-most seats—row three in the 206, rows three and four in the 207—leave little in the way of legroom.

Another comfort consideration is the baggage compartment. In spite of Cessna’s best efforts, it doesn’t quite match the capabilities of the passenger compartment. As a result, passengers may find themselves sharing space with their bags.

Performance

Top cruise speeds will run in the 145-knot area while burning 17 gallons per hour or more. Throttling back to a leisurely 135 knots cuts gas consumption to a more reasonable 13 GPH. Operating LOP can reduce those numbers two to three GPH while keeping CHTs down—a consideration in hot climate operations.

Handling matches the aircraft’s size. Pilots who enter the Stationair after climbing the Cessna model ladder may find the aircraft is just more of the same—only heavier, although the ailerons are notably responsive, even at slow speeds. Few owners seem to mind the fairly heavy controls: Snappy handling is not why they bought the airplane.

This is not without its benefits, though. It makes the Stationair an excellent IFR platform—stable and rock-solid. It also makes for a relatively smooth ride in turbulence.

Another benefit is that the Stationair is reluctant to stall. Pitch forces are fairly heavy to begin with. Compounding this is the generally nose-heavy loading of the airplane. Since the CG envelope is so long, and most everyone wants to sit up front, the CG is often at or near its forward limit. Also, with power on, the deck angle required for a wings-level stall is alarming. Put it all together and the Stationair is not generally a willing participant in stalls. If you do stall the airplane, the behavior is pure Cessna: There is a definite break and it will roll off if the ball is not centered. Recovery requires lowering the nose by at least relaxing back pressure. When heavy, especially with full flaps, it may take some altitude before you can establish a positive rate of climb.

A drawback of the forward CG tendency is a proclivity for inexperienced 206 pilots to arrive nose first during landing, especially at light weights. It takes a hefty pull on the yoke to flare properly. Thus, Stationairs are no strangers to hard, nose-first landings that sometimes damage the aircraft. In the 207, the nose baggage compartment can simply add to the nose heaviness. However, using less than full flaps for landing (say only 20 degrees) can ease the control forces required to flare. Also, as one reader aptly put it, “That is what trim was invented for: Use it.”

When loaded toward the aft CG limit the equation changes significantly. It doesn’t take nearly as much effort to flare to land. A pilot who isn’t ready for the lighter control forces can get surprised at how easy it is to get the nose up.

The 206 can feel like two different airplanes when it is light with a forward CG versus at gross weight and a mid- to aft-CG loading. We strongly recommend that any checkout in a 206 include time with the airplane loaded light and forward and heavy and aft. Part of that should be what it takes to get to the runway when heavy, with full flaps and slow. Be prepared to put the throttle to the stop.

Like most Cessna singles, the 206 does pretty we’ll in short/soft/rough field operations, a big factor in the purchase decision for many of our respondents.

Early models had 40 degrees of flap, which helped tremendously for short arrivals. However, the airplane just won’t climb with that much aluminum hanging out in the breeze. Cessna later limited flap travel to 30 degrees.

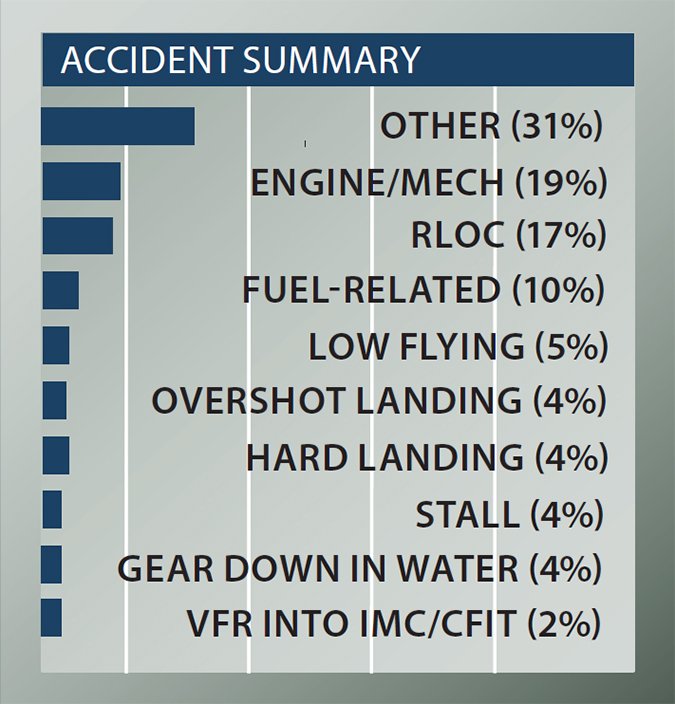

Stationair Wrecks: Other, Engine

The results of our survey of the 100 most recent Cessna 206 accidents were a reflection of the sometimes unreasonable demands made on them as utility airplanes. It looked to us as the airplanes didn’t let their pilots and passengers down—too often the pilots and mechanics let the airplanes down. Pilots either demanded more performance from them than was ever built in—one loaded his more 700 pounds over gross and stalled it on climbout—or mechanics did something wrong when working on the engine.

Of the 19 engine stoppages not due to fuel issues, over half involved mechanics over-torquing cylinder bolts or engine through bolts. In two cases fuel line attaching hardware was not tightened at all and didn’t stay attached for very long.

One owner experienced the separation of the exhaust pipe from the turbocharger. There’s a 16-year-old Cessna Service Bulletin that provides a solution to that specific problem. The owner didn’t apply the fix. Six months later the same thing happened—this time our hero had to deal with an inflight fire. While Service Bulletin compliance isn’t mandatory in Part 91 ops, we think exhaust system issues on turbocharged engines should be taken seriously.

Of the 10 fuel-related accidents, six involved pilots who didn’t carry enough fuel for the intended flight; two pilots ran a tank dry while flying low enough they couldn’t get a restart in time and two had stoppages due to water contamination.

There were 17 runway loss of control (RLOC) events. That’s a relatively low number—a good indication that the 206 has affable manners on the ground. We note that some of those were on backcountry airstrips, where 206s are regularly used and sometimes come to grief.

The ability of 206s to “take it” when it comes to a combination of load carrying and backcountry operations was reflected in many of the accident reports we reviewed. They are commonly used for Part 135 operations where there is significant pressure on pilots to fly over gross and to go no matter what, especially in Alaska. We noted one Alaska accident where a 135 pilot made a takeoff on a runway covered with three to six inches of slush. He got into the air but stalled trying to turn away from rising terrain. The high percentage of accidents in 206s that occurred in Alaska was due at least partially, in our opinion, to the “gotta go” factor.

Two pilots came to grief departing from beaches. One hit driftwood with the horizontal stabilizer, jamming the elevator. He put it into the water. The other staggered off the sand, then sank and dragged the left gear in the water to a depth that brought the airplane down.

The Stationair makes a great floatplane whether on straight floats or amphibs. It is, however, wise to ensure the gear is retracted on amphibs prior to making a water landing. Four pilots did not, leading to the assemblage flipping over. The penalty for that mistake almost always involved fatalities.

Glassy water is a hazard in all seaplane operations. One 206 pilot hit so hard on a glassy-water landing that he flipped the airplane. Another 206 float pilot was flying low over glassy water—ostensibly to check a landing area—and stuck a wingtip into the water, leading to a cartwheeling stop.

Maintenance

Simplicity is a good thing, and helps keep maintenance costs down…but on the other hand, Stationairs are working airplanes by and large, and wear and tear can easily turn the tide in the other direction.

We’ve seen problems with the tail, mostly corrosion caused by the foam-filled elevator and trim tab getting soaked with water and pulling off rivets, screws and nuts. Obviously a concern if the airplane was ever on floats.

Some of the brackets in the tail can crack. There have also been some instances of cracking door posts, though these problems have not proven to be a safety issue.

Given the number of respondents who routinely operate out of short and rough fields, combined with the nose-heavy landing tendency, we recommend paying close attention to the landing gear (particularly the nosegear), brakes and the prop for erosion from the detritus on back-country strips.

There have been a couple of 206/207 specific ADs: 85-2-7 calls for inspection of a roll pin in the fuel selector, and 85-10-2 mandates recurrent inspection or modification of the induction air box.

Other ADs of note are 91-15-4 and 82-27-2, inspection of the prop; 97-26-17, ultrasonic inspection and possible replacement of the crankshaft; 96-12-22, recurrent inspection of the oil filter adapter and 2011-10-09, seat rails and roller housing inspection.

The 206/207 is also subject to the infamous 84-10-1 fuel tank bladder AD.

Mods, Clubs

There’s probably a modification available for the 206/207 to allow it to do most anything someone might want. This includes skis, floats, long-range tanks, STOL kits, vortex generators and various speed mods.

One can even opt for an STC’d 450-SHP Rolls Royce turboprop engine, courtesy of Soloy. If that is too much, and the factory IO-520 isn’t enough, maybe an IO-550 from Texas Skyways would be your power solution.

As far as type clubs, the Cessna Pilots Association is your one-stop shop for all things Cessna. The Cessna Flyer Association also comes highly recommended.

Owner Comments

I was involved with a skydiving group out of Iowa, and somehow we ended up owning a 206. For a group of jumpers who wanted a fun plane that worked its butt off every weekend it was hard to beat.

The airplane almost always went to the annual with no major maintenance issue. We stripped out the seats, except for the pilot’s, and removed the door. And yes it was cold the times we flew in the winter.

For an instrument panel we had a VHF radio and a compass that worked. I think the fuel gauges were mostly working.

Since we just flew over the airport we just measured the gas with a stick. If it was wet, there was enough to get to 7,500 feet. Gravity always seemed to bring it back down pretty well. We rarely did cross-country flights (except for those trips to Mardi Gras, whoo), so we weren’t that concerned with efficient travel.

We could put in six jumpers and the pilot and get to 7500 feet and back down three times per tach hour. It was almost like the more we abused it, the more it loved us.

We had no mods on this wonderful plane, not counting on removing the seats and doors, but it was a true STOL aircraft. The field we were based at had a 3000-foot main runway, north and south, and a 700-foot diagonal. Because all you did was takeoffs and landings, you could get pretty good at bringing it in and stopping easily on the 700-foot grass strip.

The trick, if you can call it that, was understanding how to trim it when 1200 pounds of people and gear exited. If you trimmed it to fly neutral, you simply ran out of elevator when it came time to flare, and you ate up a lot of runway. If you kept the trim the same as when loaded (the plane, not the pilot) all you had to do was put out full flaps, slow it down till the needle bobbled around 50 knots, and carry a little power. Once on short final, about 200 feet out, start flaring and cut the power as you went over the cornfield fence. You had to really haul back to get a good flare, but if you did, it easily stopped in 300 to 400 feet.

John “Mac” McCarthy

via email

I bought my 1980 U206 in 2006 for $185,000. It had a new interior and upgraded avionics. I bought it for personal use as there is six of us in our family, including my 6-foot-4-inch son. We live in Oklahoma and fly it regularly to Arizona. I’ve averaged putting about 70 hours a year on the airplane.

Insurance was initially over $7000 a year as I was a 58-hour pilot. Once I got my instrument rating the rates went down to where I now pay $2004 for a $1M smooth policy. Average cost for five annuals has been $1539. I’ve added some avionics and GAMIjectors. In the time I’ve owned the airplane I’ve only had to replace the spinner, EGT probe, battery, a fuse and repair the beacon and the brakes.

I normally cruise between 9000 and 11,000 feet, LOP, burning 12 gph at a true airspeed of 138-140 knots.

I purchased the airplane so the entire family could travel together. I looked at the 206, 210, Cherokee Six and the Lance/Saratoga retractable. I opted for the weight-carrying ability of the 206 and a non-retract because of my limited flying time, plus the high wing matters when dealing with the Arizona sun. I did not look at 206s with fuel bladders as I did not want to deal with their potential problems.

The ability to carry a great deal of weight is important to me because I prefer to fly with full fuel for safety, and can do so in the 206 and still have a big load in the cabin. It is slow, but I do not feel as if it ever gets ahead of me. It is a great instrument platform but it is also a lot of fun to just fly around for sightseeing or in the pattern shooting landings. I think the slow speed, especially at the stall, makes for safe touch and goes.

My best story came out of a sad event—my daughter was badly injured in a skiing accident, suffering numerous fractures. Driving to the airport for the trip home was agonizing for her. The 206 proved to be the best airplane ever. We used the big cargo door opening to easily get her into the fully-reclined rear seat, strapped her in and stuffed pillows around her. She slept comfortably all the way home.

Richard Greisman

via email

I have flown several 206s on floats, one on PKs, the rest on Edos. The Edos seemed to be a good design for the 206, almost always easy to get out of the water even when loaded; the 206 with PKs was a dog. My flights were in and out of lakes and rivers in Alaska and in salt- and fresh- water operations from Seattle north to the Inside Passage in British Columbia, Canada.

On floats, the 206 with the IO-520 engine required that the cowl flaps be open at all times to get appropriate cooling. The operator I flew for called for takeoffs at 25 inches and 2500 rpm, mostly to keep the noise level down. Unless the airplane was heavily loaded, or the area was tight, the reduced power takeoff was manageable.

Heavy, full power was necessary, sometimes pressing against the five-minute limit, especially on glassy water.

An issue that came up regularly was carrying too much in the back end, either passengers or baggage. Even though the airplane was in CG, it could be a real challenge to get the floats up on the step on takeoff. If you couldn’t get on the step the CHTs would redline and the five-minute limit on full power would get hit and you’d have to go back and do something to change the loading.

The rule of thumb most of us used was that if the tails of the floats started to look even with the surface of the water before the pilot climbed on board, you were headed for a challenging takeoff. This is where the 206 on Edo floats mattered to me. If I could get the airplane on the step, it would eventually come off the water, even if you had to lift one float at a time on glassy water. On PKs, getting on the step did not guarantee the airplane would come off the water; I might end up just high-speed taxiing.

The 206 flew we’ll on floats with a good load, handled turbulence we’ll but didn’t seem to like flying too slowly on final approach as it would develop a very high sink rate. The pilots I flew with and I found that a power-on approach was the best for managing gusts and sink rate, with a little bit of power carried all the way to touchdown.

Greg Bedinger

via email

I purchased a new turbo 206 in early 2008, base the airplane in Denver and use it for business and personal travel around the western half of the U.S., often crossing the high mountain ranges of the west. When I was evaluating alternatives, I considered a variety of cabin-class twins and six-place singles. Ultimately, I decided to go with a new 206, which provided a platform for gaining experience flying with a glass cockpit and would give me decades of reliable service, hopefully following me into retirement.

Some of the add-ons to the airplane were extended range/tip fuel tanks, gap seals, active traffic (TAS) and XM weather. The extended fuel tanks provide an interesting combination of higher useful load (1420 pounds), increased range with nearly 120 gallons of fuel on board, higher cruise speed and lower stall speeds. I don’t usually fly with fuel in the tip tanks, except for very long trips. The full-flap, power-off stall speed has dropped to an unbelievable 35 knots indicated when lightly loaded.

The TIO-540 engine seems to be happy at 18 gallons per hour at maximum cruise at nearly all altitudes giving speeds from 160 knots at 12,000 feet to 170 knots at 18,000 feet.

As an instrument platform, the airplane is exceptionally stable in every weather condition that I’ve encountered—no sick passengers, yet. It took some effort to become proficient with the G1000, but it was worth every minute. Landings are predictable and smooth, even in the high crosswind conditions that Denver enjoys every once in a while.

So, obviously, I’m pretty high on the 206. It provides a great combination of huge loads, reasonable speeds, crazy endurance and good maintenance costs that are common to Cessna products.