The Beech Sierra’s entry into the normally aspirated 200-HP piston single market was—like its competitors’ offerings—a growth airplane derived from an earlier model with less horsepower and less complexity. That was the Model 23 Musketeer, of course. Like Piper’s Arrow and Cessna’s Cardinal RG, the Sierra sports four seats, a constant-speed prop and retractable landing gear, making it a logical step-up for newer pilots and owners looking for something a bit more than a trainer-category aircraft. While it’s no speed demon, there’s a lot to like about Sierra ownership.

Like the Musketeer—and most any product from Beech, for that matter—the Sierra is well-known for quality components and construction, as we’ll as comfort. Owners admit that the Model 24R Sierra isn’t the sleekest of the 200-HP crowd and it certainly isn’t the fastest. It might be the most comfortable, however, and perhaps the most reliable.

History

Beech’s Musketeer was the company’s answer to the Cherokees and Skyhawks of the world. The first of that line, the Model 23, came to market in 1963. Three years later, the Model A23-24 Super III debuted. With 200 HP and fixed gear, it wasn’t nearly as fast as the same-power Mooneys of its day (the Arrow and Cardinal RG hadn’t been introduced yet). In 1970, Beech made the decision to fold the A23-24’s landing gear, resulting in the Model A24R, or Super R.

The Sierra name came with the B24R in 1973. Also, Beech one-upped Cessna, Mooney and Piper by making the A23-24 and the 24R models nominal six-seaters, if so ordered from Beech; they cannot practically be retrofitted with the aft seat, due to structural differences.

It gained some speed, but still lacked some of the better, more utilitarian features that would make its successors much more likeable. It did, however, have the hallmark of all Beeches: It was comfortable (as in roomy) for the occupants. In a general aviation world where most designs crammed people shoulder-to-shoulder, this alone was a good selling point. The Sierra (and fixed-gear Sundowner) cabin is two inches wider than any Bonanza or Baron.

While it was an option in 1970, in 1971 Beech capitalized on the design’s comfort by adding a second cabin door along with enlarging the baggage door and moving it to the left side.

These changes made loading and unloading much easier. The split passenger seats could now be removed literally in seconds, for loading pets, bikes or cargo. Many also discovered the big aft door, with its child-resistant inner handle, was perfect for placing squirming children in the rear jump seat. In 1973, Beech introduced the new instrument panel featuring quadrant-style engine controls. They also changed props, going from the original McCauley to a Hartzell.

In 1977, the C24R was introduced. Last of the line (production ceased in 1983), the C model featured several improvements. New aileron bearings resulted in a smoother control feel. Usable fuel was again certified at 28.6 gallons per side, following a brief hiatus involving misoriented fuel pickups in some tanks.

The cabin vent system was changed, improving what was already an excellent system by most owners’ reckoning. A larger-diameter prop was hung out front to provide a bit more thrust. A rather modest drag-reduction program was instituted and leading and trailing fairings were added to the main wheel wells, plus gascolator and battery venting.

The ailerons gained nominal gap seals. In fact, the changes made in mid-1978 and 1979 could easily have qualified for a D-model designation and included a 28-volt electrical system, different brake calipers and disks, and much more.

All models, even the fixed-gear Super IIIs, were powered by a 200-HP Lycoming IO-360, with the retractables getting the -A1B6 version. Total production for all retractable 24R versions came to 793.

Comfort And Utility

The Sierra’s cabin comfort has always been one of the design’s better points. Owners tend to rave about it. Beech has always been known for building airplanes that didn’t squash occupants, and the Sierra was no exception. But there’s a price to pay for comfort, and in the Sierra as in so many other designs (like the Rockwell 112/114), the penalty for all that space is greater fuselage wetted area, translating into drag. The partially unenclosed landing gear does nothing to help here, particularly on the A and B models.

If there’s one uncomfortable aspect of the Sierras, it’s noise, probably resulting from the numerous windows. These days, with noise-canceling headsets, that’s not as big a problem as it was in the day. If refurbishing a Sierra, thicker glass is an option, especially if you’re willing to trade some useful load for noise reduction, while sound-insulating foam in the doors and sidewalls might be a better way to spend money as today’s ANR headsets do solve the noise issues.

As mentioned, and despite the windows, the fresh-air vent system—especially on later models—is capable of keeping back-seat passengers from frying under the summer sun. In winter, the heating system is able to get warm air back there, too, preventing cases of flying frost.

Yes, you could get all six pax in there and still have enough load ability left to carry 50 gallons of fuel (and remain within the CG envelope, too). There aren’t many 200-HP airplanes that can do that realistically, if at all.

If it’s not people you want to haul, the Sierra still may be a good choice: The rear compartment is rated to a staggering 270 pounds. And, unlike many other aircraft, that’s not just a marketing number. It’s entirely possible to toss in all that with two adults up front. The middle and jump seats will have to be vacant, but most of the competition couldn’t do this, anyway. If you’re ever going to haul Uncle Ernie’s antique anvil collection, it’s nice to know you can do it with a Sierra. Owners have reported hauling kitchen ranges and clothes dryers, shower door sets, two-blade constant-speed props and other unlikely cargo.

The Sierra’s 60-gallon fuel capacity enables a wider tradeoff between range and effective cabin payload. As one result, comparing a Sierra to its competition’s full-fuel payload can be misleading (yet we’ll still do it on page 25). But few of the competition allow as much load flexibility as the Sierra—having a higher useful load is useless if CG or access restrictions prevent you from using it. The Sierra’s useful load is more of a real-world thing. An IFR-equipped Sierra can haul three adults, 60 pounds of baggage and full fuel. Or fill the seats, keep the baggage loaded and still have more than two hours in the tanks.

Performance

Going somewhere? Don’t be in a rush. Speed is not the strong point of these smallest-engined of the retractable Beeches. As we’ve hinted, what the large print giveth in comfort, the small print taketh away in drag.

Consider the Rockwell 112. It, too, is known for its comfortable, roomy cabin. And, like the Sierra, it’s not known for getting places quickly. The Piper Arrow, also with an IO-360 bolted up front, books in about 7 knots faster. Cessna’s Cardinal RG, also the same basic engine, has about 11 knots on the Sierra. At the far end of the scale is the Mooney 201, which traded cabin space for speed and comes out a blistering 20-plus knots faster.

Something important to keep in mind here, though: Most comparisons are based on book numbers. Reports from the field tell us the Sierra will nearly always meet or beat the book numbers. Others? Not so much. And if you are really after max fuel economy on a local burger run, you can operate a Sierra lean of peak at an indicated airspeed of about 95 knots and burn only 4 GPH. That’s Light Sport territory, with a huge cabin.

So the Sierra isn’t going to get you anyplace fast. And it’s also not known for getting in and out of tight fields with any degree of aplomb. Some owners consider their airplanes to be fit for paved-runway duty only. Short grass strips are not normally an appropriate venue for the Sierra, at least with an inexperienced pilot behind the controls. However, owners tell us low-speed operations based on the go-around configuration, as outlined in performance charts, allow Sierras to easily handle most common turf strips.

Handling

Like most of the Beech line, the Sierra is considered an absolute delight in the air. The controls are light and smooth, and fluid handling through graceful maneuvers is a breeze. The controls make it handle like something lighter, while providing a smoothness normally found only in much larger aircraft. Owners boast that the Sierra’s full-deflection roll response is impressive.

All this is true, until you try getting the thing on the ground. While the Sierra may be slow in cruise, it’s pretty fast on landing. VSO is 60 knots, making for a fairly high approach speed. For comparison, consider that the Mooney 201, considered a “hot” landing airplane, actually has a stall speed 5 knots slower than the Sierra. Other competitors, like the Arrow, also have lower stall speeds (11 knots slower in the Arrow; 9 for the Rockwell 112B).

So, your speed down final is a bit higher to start with. And speed control is absolutely vital in the Sierra. A bit too fast and she’ll float badly. As you slow, the stabilator’s declining authority can lead to some pretty wild oscillations and over-controlling. It’s not a pretty picture. Try coming down final a bit on the slow side and you’re in for a hard nose-first arrival, unless you carry some power.

The same stabilator that had so much authority when the airspeed was too high tends to run out of ability when the plane gets too slow—especially at forward CGs. This generally results in a wheelbarrowing landing. On the other hand, if you get the nose up while the airspeed is too low, the escalating sink rate makes for a hard landing—same result, just for different reasons.

Compounding all of this is the fairly stiff trailing-link landing gear. The shock absorbing system consists of rubber donuts, as on a Mooney. These have never been noted for their give, and age does nothing to soften their disposition. That said, what you give up in shock absorption might be gained back from savings on conventional strut maintenance. If there’s a secret to getting good landings out of the Sierra, it’s carrying some power into the flare. A little throttle jockeying can go a long way toward making for a smooth touchdown, provided your airspeed is right on the money.

To be fair, most owners report no problems at all with landing qualities. And on the plus side for landings, the Sierra’s gear has an admirably wide stance and can handle tremendous impacts. Crosswinds are easily handled with a crab to the flare and then dropping the upwind wing just before touchdown to straighten out the nose. At the same time, avoid coming down final in a slip. The airplane is placarded against slips of more than 30 seconds in duration, due to fuel unporting problems if the low tank is selected during uncoordinated flight.

Despite these vices, the Sierra is a most pleasant airplane, at least up until landing. The stall is gentle and gives good advance warning. At forward loadings, it’s more likely to simply hunt the nose up and down with a prodigious sink rate, rather than snapping down or over if the ball is not kept centered.

One handling virtue of the Sierra is the great strength of the landing gear in flight. As a speedbrake, with those huge flat-faced castings, gear-lowering speed is pretty close to cruise speed—you can drop them at up to 135 knots. If you need to get down fast, or slow down fast in an emergency, dropping the gear is a good way to do it. Owners tell us the Sierra can handle a slam-dunk approach with aplomb: Fly it at 140 knots or more down final with the gear up, then close the throttle, throw out everything and land safely from a quarter-mile out. Spiraling down at rates exceeding 3000 FPM is reportedly possible, without exceeding any limitations.

Maintenance

A recent review of FAA Service Difficulty Reports (SDRs) indicates some common items require regular attention. Broken nosegear steering lugs (from bad ground handling), nosegear actuators that internally bypass fluid, cracks in the nosegear yoke (usually impact damage), binding or broken nosegear downlock springs and so on all added up to indicate that the nosegear merits special attention, as is really the case on any aged retractable. Owners tell us the auxiliary nosegear downlock switch called for in Beech Service Bulletin SB-2683 is really a must-have on a Sierra, but most are still missing that switch.

We also found several instances of airframe components requiring repair or replacement due to cracks or corrosion. From our research, fuselage components coming in contact with fresh air ducting need close examination, as this apparently is an area experiencing rampant corrosion. The Sierra’s type club, the Beech Aero Club, has teamed up with a supplier that provides premium replacement parts for the standard ducting.

The Sierra has had its share of type-specific and shotgun ADs, but most of these are better than 20 years old and should long since have been complied with. Some relatively recent ones are: 89-24-9, aileron rod end bearings; 88-10-1, replacement of fuel boost pump; 87-2-8, inspect the stabilator hinge fasteners every 100 hours; and 85-5-2, modify the guard on the fuel selector (this guard had been replaced as the result of a 1975 AD). Owners tell us none of these ADs have proven onerous thus far.

When searching for a good used Sierra, there are some points to remember. One of the first things to look at is the front end. Examine the engine mount and firewall for evidence of a hard wheelbarrow. This is where the damage occurs, so a careful check is in order. Also, examine the logs carefully for evidence of a gear-up landing. Another item to look for in the logs is replaced aileron rod end bearings. Over the years there have been many instances of these concealed forward bearings seizing due to lack of proper lubrication during 100-hour servicing, leading to stiff or even frozen controls. Ultimately they were targeted by AD 89-24-9, which calls for installing inspection ports and inspecting the bearings every 100 hours. All of the C-Model Sierras came from the factory with the improved inspection and lubrication access.

Mods, Type Club

Perhaps due to the relatively low production numbers—only 793 retractable Model 24 airframes left Beech’s now-closed Liberal, Kansas, factory—or maybe because owners are happy with their decision, few modifications seem to be available for the Sierra. Nothing, at least, like its bigger brother, the Bonanza. Sure, one can install just about any electronic gauge or avionics one wants, including a Garmin G600 glass panel or Precise Flight‘s Pulselite control unit for landing/taxi light systems. But the list of available airframe mods isn’t a long one.

Globe Fiberglass and a couple of other suppliers offer fiberglass wingtips and other fairings, which reportedly are far preferable to the crack-prone ABS plastic ones Beech put on at the factory. Meanwhile, Micro AeroDynamics offers a vortex generator kit for wings, stabilator and vertical stabilizer it says will reduce the clean stall speed by as much as 10 knots, with a correspondingly shorter takeoff and landing roll. This might be just the ticket to cure the Sierra’s runway-related shortcomings, including regular operation at unpaved strips.

Hands down, the best resource for Sierra owners is the Beech Aero Club, an internet-based type club. The organization takes its name from the way in which Beech marketed its training and personal aircraft beginning in the 1960s. Its website has plenty of resources you’d expect from a type club, including AD listings, contact info for CFIs experienced and knowledgeable with the type, service bulletins and—through experienced owners—a wealth of knowledge. Another online resource is Beech Talk, which is focused on Bonanzas and Barons, but also enjoys active participation among Musketeer, Sport and Sierra owners.

Bent Sierras: Engine/Mechanical

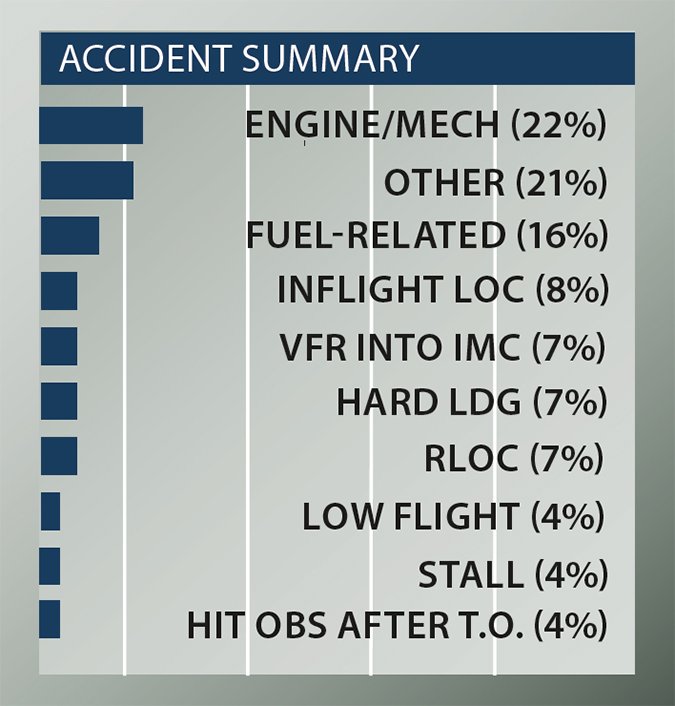

We were impressed by how few Beech Sierra accidents there have been—we had to look back 40 years to find a full 100 accidents to review. We were also impressed by the absence of runway loss of control (RLOC) accidents—only seven, by far the fewest for any type we can recall in years of doing accident reviews. It’s a testament to the airplane’s manners on the ground.

There were only two gear-up accidents, less than half of what we expect to see on folding-gear birds.

Engine/mechanical issues brought down 22 Sierras—and virtually all of those were due to improper maintenance, not something wrong with the design of the aircraft or engine. We saw the usual malpractice: from fuel lines that were left disconnected or only connected finger-tight, through cylinder bolts that were improperly torqued to the wrong fuel pump being installed.

We were fascinated by two gear-related events: In one, the nosewheel fell off just after takeoff (the pilot brought it back around and had a noisier than normal rollout); in the other, the nosegear started to retract during the takeoff roll and the prop took divots out of the pavement as it started to pretzel itself. Amazingly, the pilot pressed on. Once in the air, he reconsidered the flight and set up for a landing on a nearby road. He hit trees with a wingtip before touchdown leading to a loss of control and extensive damage to the airplane.

Of the inflight loss of control, hard landing and stall accidents, 11 were precipitated by a cabin door coming open shortly after takeoff. Several pilots attempted to return for landing while flying the pattern at altitudes we’ll below 500 feet and then either stalled or lost control.

The POH says that aircraft handling is not adversely affected by an open door; however, rate of climb will diminish by at least 150 FPM. Our takeaway is that if the door comes open, focus on flying the airplane, maintain airspeed and do everything as normally as possible rather than cut corners trying to land as soon as possible.

Over half of the fuel-related accidents involved pilots who ran a tank dry and either didn’t switch to the other tank, didn’t do so in time for a restart or didn’t follow the restart procedure in the POH. There is no “both” position on the fuel selector, which, from our review of thousands of accident reports, means that some pilots will manage to mismanage the fuel system and not make use of all the fuel they have on board.

Falling into the “other” category were several takeoff accidents in which the pilot tried to get performance out of the airplane that was never built in. The Sierra is not a short-field airplane—and attempting to take off downwind or at high density altitudes should only be done with lots of runway available. Several pilots complained that their airplanes didn’t seem to want to accelerate or climb after they had aborted takeoffs and went off the end of the runway or hit obstructions after takeoff.

There were two inflight breakups: one VFR on an overcast night, the other IFR. In both cases there were thunderstorms in the immediate vicinity. VFR into IMC claimed seven Sierras. Most of the accidents were fatal; however, one pilot was able to land after he flew into low clouds and then hit a guy wire on a tall tower.

Owner Comments

Although the Beechcraft Sierra was marketed primarily as an advanced trainer aircraft for commercial pilot and CFI students, it is a remarkably capable personal traveling machine. I have owned and operated my 1981 C24R for over 15 years and 2500 hours of personal flying.

My Sierra came out of the factory as a six-seat plane, but I fly and insure it as a four-seat plane, enjoying extraordinary baggage space and access. The three large doors make loading passengers and baggage easy. The wide CG envelope makes it easy to load light or heavy and still stay within limits. There is a noticeable increase in climb rate and speed once weight is a few hundred pounds below gross, but it still makes book performance numbers at maximum gross weight.

The Sierra is not the fastest cruiser or the best climber in the 200-HP complex class, and it is not a short runway hero. But, the balance of all these combined with exceptional cabin comfort and operating efficiency makes the Sierra perfect for my needs. I often load baggage and two adults, top the fuel tanks and fly more than five-hour legs at 130 knots. My home-to-destination block times are often far quicker than many six-cylinder planes with similar loads. The low fuel burn allows me to forego a fuel stop that many other singles would need on these types of trips. I routinely plan on 9 GPH fuel burn at 130 knots. With 57 usable gallons of fuel, we are all ready to get out when we get close to my one hour reserve limit.

Compared to the fixed-gear Musketeer, the cost of maintaining the retractable gear and the constant-speed prop are we’ll offset by the faster cruise speed with lower fuel burn. If used for longer trips, the Sierra makes financial sense over the fixed-gear versions.

0)]

I have periodically updated my IFR avionics and found that the panel has plenty of room for the current large screen displays. The later 24-volt electrical system allows plenty of battery reserve to keep it operating in case of alternator problems.

Beech generally turned out its models with adequate corrosion protection and my plane has had no problems living near the ocean. The only real corrosion issues seemed to come from the old black steel wire scat hose that Beech used as ducting. I replaced all mine years ago with modern ducting. When doing a prebuy exam, examine the ducting and know that black hoses are the bad ones, while the replacements are red.

The biggest financial benefit comes at overhaul time. I think the IO-360 has lower maintenance and overhaul costs then the six-cylinder engines of the similarly performing Cessna 182, which was a consideration during my shopping. My starting annual inspection cost is the same as my shop charges for all similar small retracts. I tend to do a fair amount of preventive maintenance, so I rarely end up paying for a basic annual inspection. Parts that are specific to the Sierra model are rarely needed and there are some specialty sources. In the 15 years owning this Sierra, I have not found any parts that were impossible to find.

The Beech Aero Club organization is an absolute must-have for a Sierra owner. It has saved me a lot of money and time over the years for sourcing parts, advice and old documentation. There is a strong group of owners, pilots and A&Ps in the group and most questions posted on the website get a legitimate answer within a few hours.

My insurance, which is based on lots of time in type and an $80,000 hull value and $1 million dollars of liability with no sublimits, is roughly $1300 yearly.

In summary, after 15 years and 2500 hours of Sierra ownership, I can’t think of a better plane for my needs. In today’s market, the Sierra is nicely priced among other traveling machines. It is thoroughly capable of comfortably carrying myself and three friends from Virginia to the Bahamas with one fuel stop. Maintenance is relatively simple and there are few ADs. It’s also an easy plane to fly, given its initial design goal as an advanced trainer. You can use it for training flights or $100 burgers, plus it’s roomy enough for long trips. That’s a balance that is tough to beat.

Paul Wurbin

via email

I‘ve owned a 1977 C24R (N699DK) since May 2013. I was casually looking for a Sierra because I had trained for my private pilot certificate in the late 1970s in a BE19 Sport at the University of Illinois. I admired the aircraft’s sturdiness, roominess and stability.

Compared to the Sport, the Sierra offers more speed and a cavernous 24 by 30 foot baggage door. Another selling point is the easy removal of seats for added carrying capacity, plus the large fuel tanks.

Maintenance has been straightforward and the IO-360 engine is reliable going into the 1900-hour mark. I’ve replaced the main gear donuts last year with an aftermarket set, which was roughly $550 for each gear. That’s not cheap, but the old set was original. Annual inspections have averaged $2000 because I have a very thorough IA. Fuel burn is between 9 to 10 GPH and cruising speed is 120 to 125 knots.

Last winter I added GPS and ADS-B capability with an Avidyne IFD540 and Avidyne AXP340 1090ES transponder. Beacon Aviation in Grand Ledge, Michigan, did a great job cleaning up and painting the panel.

Overall, I’d say this is a great aircraft for me. It’s not the fastest in the class, but it’s certainly comfortable, roomy (I’m 6 foot 4 inches tall and weigh 240 pounds) and a great IFR platform. It’s also a great value—comparable complex singles usually demand as much as $20,000 more than a Sierra.

David Hast

via email

I purchased N1960, a 1976 B24R, in November 2010 at the age of 30 and with a total of 10 hours experience (all in Cessna 172) as a student pilot. Many folks advised me to purchase a 172 and then resell it once I completed my training. Since the hardest part of the purchase was convincing my wife that airplanes are a good investment, I had to look for something that was economical, within our budget ($30,000 to $60,000) and could serve us for years to come.

It was almost by accident that I stumbled upon the Beech Sierra, but it didn’t take long to see that this was one of the most efficient and economical airplanes ever manufactured (especially for our budget). Where else can you find a 135-knot airplane with one of the most reliable and efficient 4-cylinder engines available, a 900-pound useful load, a range of over 600 miles, plus the widest and roomiest cabin in class—with two entry doors and full-size cargo area that can hold up to 270 pounds—all at an entry price we’ll under $60,000?

The Piper Arrow makes the best attempt at comparing itself to the Sierra, but all it takes is a look inside the cabin and one flight to see the Sierra separates itself from all of its competitors. The large cabin combined with a stable platform in turbulence provide exceptional comfort for pilots and passengers on long cross-country trips. The large cargo door allows for you to haul big bulky items. I have placed as many as seven large travel bags in the baggage area, plus I have hauled two sets of golf clubs and baggage for three adults.

I now have over 500 hours in my Sierra, and I completed both my private pilot certificate and instrument rating in it. I’m currently working on my commercial certificate.

My annual runs about $1200 for a basic inspection and insurance is about $1200 (with an insured amount of $65,000). I flight plan for 9 GPH in cruise. I figure my operating costs are around $75 to $80 per hour, including insurance, annual inspection, fuel, oil, engine and prop reserve. Obviously this varies with amount of hours flown and I average around 125 hours per year.

The most valuable recurring cost is my Beech Aero Club membership. A nominal yearly fee of $50 provides full access to a club focusing solely on the Musketeer/Sierra. This has saved me thousands of dollars in labor and parts. I have posted questions related to operation or maintenance, and within minutes received multiple responses from members.

When I purchased N1960L (for around $45,000), it had new custom paint and interior, a midtime engine, a three-blade McCauley prop, IFR avionics, plus an S-TEC two-axis autopilot.

We have invested in upgrades for the airplane—most of which have been avionics—including a Garmin GNS430W, GMX200, Century HSI, Dynon D2 and a L-3 Lynx NGT-9000 ADS-B system. Despite adding these avionics, we have managed to keep pace with the average book value of the aircraft.

As for performance, our Sierra doesn’t disappoint. Critics are quick to point out the trailing-link landing gear, and what they feel is an underpowered engine for the airframe. The weight of the gear might slow the plane’s top end speed a bit, but you can have full confidence that it can withstand a lot of imperfect landings. At roughly 900 FPM at 105 to 110 MPH on most days (figure 500 to 600 FPM for max gross takeoffs on hot days), it’s an average climber.

The Sierra has an aileron/rudder interconnect system, which can make the controls feel a bit stiffer than other light singles, but responsive enough to ease hand-flying in turbulence.

The airplane has an excellent CG envelope and allows for several configurations of fuel, baggage and passengers. The Sierra’s CG moves forward as fuel burns off.

Overall, I think Beechcraft achieved its goal of developing and manufacturing an economical cross-country airplane that’s designed for the regional business traveler or a recreational pilot looking to get away with the family for the weekend. The Sierra reflects the Beechcraft quality, while also providing excellent efficiency.