It’s routine: We get in, strap in without thinking about it and beginning running the checklist. Putting on and tightening up the restraint system is probably the most basic of automatic tasks any of us do as pilots—without the reassuring pressure of the belt and shoulder harness attaching our torso to the airplane, most of us wouldn’t hit the starter.

Restraint systems keep us firmly attached to our seats in turbulence so we can control the airplane when it’s gyrating and they make a huge difference in whether we’re going to be injured or killed when things go south and the airplane comes to a stop in circumstances other than we desire.

While restraint system use is automatic for most of us, as aircraft owners and users we also need to inspect the restraints in the airplanes we fly. But, what are we looking for? How do we know when a seatbelt needs to be repaired or replaced? And, if it does, what are our options?

How Much Wear?

The FARs call for following the manufacturer’s maintenance instructions; however, there simply are not definitive guidelines for what is acceptable wear and what isn’t. As Scott Utz, proprietor of Arapahoe Aero in Denver, told us, “Restraint systems are on-condition replacement items, but there’s nothing comparable to the guidance you get with other components that says such things as a quarter-inch crack is acceptable, a half-inch crack is not.” He went on to tell us that anytime you observe frayed, torn, creased or crushed webbing (fabric), it should be repaired or replaced—any one of those items is a condition. So are broken, missing or frayed stitches. If the stitching pattern is inconsistent, it may indicate rewebbing by someone not qualified to do the job.

We also learned that the hardware should be inspected for wear or bending of hooks and end fittings, inoperable springs and rust—all are conditions that call for replacement. If the buckle shows wear or doesn’t operate properly, it should be replaced. One of the big problems is the connection between the belt and shoulder harness of older Cessna restraint systems that had a separate seatbelt and shoulder harness—if the shoulder harness does not attach firmly to the seatbelt and stay attached through all flight operations, the connector(s) should be repaired or replaced.

If the restraint system is in use during a quick stop—there’s been any damage to the airplane and the system was loaded by the occupant—it should be pulled and repaired or replaced. If a restraint system has been loaded there’s no guarantee it will be able to handle its certified nine or 16 Gs if loaded again.

During our research the one consistent guideline we saw from manufacturers, repair shops and publications on restraint systems was that the useful life of webbing is 10 years. UV rays break it down, weakening it.

Repair, Replace, Upgrade

The good news is that there are a lot of options for the owner facing worn restraint belts and the most basic—rewebbing—is not particularly expensive and rarely takes even two weeks to accomplish, including priority shipping. If it is time for your restraint system to be rejuvenated, you may want to take advantage of the upgrades available, especially if your airplane doesn’t have shoulder harnesses installed in all of the seats or it doesn’t have at least four-point, inertia-reel harnesses in the front seats. We’ll survey what’s available.

Rewebbing

While buying a new set of restraints from the aircraft manufacturer is fine, the more cost-effective method of getting the same result is to send the current set—hardware and all—to a shop that specializes in rewebbing.

Cindy Vandereedt, office manager of Aviation Safety Products in Blairsville, Georgia (www.aircraftseatbelts.com), told us that her company normally turns around restraint systems sent in for rewebbing in five to seven days.

The procedure involves an inspection of the hardware—including the inertia reel, if part of the system—to confirm it can be reused. That is usually the case. The old fabric is discarded and new webbing is sewn onto the hardware using the stitching pattern and thread approved for the particular type of belt or shoulder harness so that it will meet the nine or 16 G (as appropriate) FAA requirements for it. Vandereedt told us that an X-pattern stitch is normally used. If any of the hardware has not met inspection criteria, it is replaced.

Once the belts and harnesses have been built up, each is visually inspected for conformity and condition of the hardware, including functioning of buckles and inertia reels. The FAA 8130 Airworthiness Approval tag is filled out and the assemblies are shipped out.

As part of quality assurance and confirmation that rewebbed belts conform to their type design and FARs, rewebbing operations periodically test that completed belts meet pull requirements and the webbing meets burn requirements.

Our survey of prices for rewebbing restraint systems showed that the industry is competitive. Prices for seat belts alone start in the low $60 range and increase with the complexity of the system to about $240 for the most complex system—a five-point, rotary release system with inertia-reel shoulder harnesses.

Upgrades

We strongly recommend that if you have an airplane that does not have shoulder harnesses for all of the seats that you install them if at all possible. It can be done on most, but not all, general aviation airplanes. We’ll talk here about passive restraint systems (once installed, they do their job of protecting occupants without further ado) as we covered active (airbag) systems in the June 2017 issue.

In some airplanes, such as on most Cessna singles and the 336/337 series, the hardpoints/nutplates for shoulder harnesses were installed in the overhead structure when the airplane was built even if shoulder harnesses were not installed. Installing shoulder harnesses can be easy. We watched it done in 15 minutes for the rear seats of a Cessna Cardinal.

For many aircraft, the upgrade is nothing more than what the FAA refers to as a minor modification and requires only a logbook entry. AC 23-17C (at page 101) has guidance. Generally, if there is a hardpoint or structure where a shoulder harness can be attached, it’s a minor modification. Hey, the FAA knows the value of shoulder harnesses and doesn’t want to put roadblocks in the way of installation where there is good structure. The Advisory Circular applies to the front seats of airplanes built before July 19, 1978, and the rear seats of airplanes built before Dec. 12, 1986.

The second method of upgrading a restraint system is via STC, which is most often the way to go when adding the more sophisticated restraint systems.

The following is a brief survey of upgrade options available for most GA airplanes.

Aero Fabricators offers a Y-type, four-point harness kit—a shoulder harness over each shoulder attaching to the seatbelt—through Wag Aero (www.wagaero.com). They are STC’d for either the front or all seats for most of the Cessna 100 and 200 series, fabric-covered Pipers and the PA-24 and -28 series as we’ll as Beech 35s, some Stinsons and Aeroncas. Starting at $162 per seat for these fixed (not inertia-reel) systems, we consider the prices so low that there is no reason not to upgrade.

Alpha Aviation (www.alphaaviation.com) sells replacement and upgrade three-point fixed-strap and inertia-reel kits for a wide selection of Piper, Beech, Cessna and Ercoupe aircraft. In most cases, the belts are for the front seats only. Prices start at $349 per set for fixed-strap kits with inertia-reels being about $100 higher.

BAS (www.basinc-aeromod.com)offers a line of inertia-reel four-point restraint systems manufactured by AmSafe. They are available for what seems to be an ever-expanding list of Piper, Beechcraft and Cessna aircraft as we’ll as Luscombes—although they tend to be limited to front seats only. Prices begin at $1480 (black)/$1500 (color) for a pair of front seats. Check with BAS for exact pricing and rear-seat availability.

Hooker Harness (www.hookerharness.com) is known for its aerobatic restraint systems but it also offers a line of fixed three-, four- and five-point harnesses for the front seats of most GA aircraft. Prices start at $275 per seat.

Shoulder Harnesses: A Magic Bullet For Safety

From the perspective of an aircraft owner, it seems that anywhere you look someone is trying to sell you something that is guaranteed to make your ride’s panel the hottest on the airport, or reduce drag so that it’s faster and more efficient or reduce the stall speed so that it can take off and land from a postage stamp.

Almost invariably, the advertising includes a claim that installing the product will make your airplane safer. It may even be true. However, for an aircraft owner on a budget, what is the one product that gives the absolute most bang for the buck in terms of increasing the level of safety of the airplane? The answer is: shoulder harnesses, for all of the seats.

While owners spend big bucks for avionics to avoid midair collisions, those make up only 1 percent of aircraft accidents. Interestingly, more than half of the people involved in midairs survive.

When you do the safety and accident risk analysis for GA aircraft it turns out that the big accident risk is runway loss of control on takeoff or landing (RLOC). In tailwheel airplanes the rate of RLOC accidents can approach 50 percent—and they tend to be the airplanes that don’t have shoulder harnesses for all of the seats.

With the highest single accident exposure being RLOC events, the next step in the safety analysis is whether those accidents are survivable and whether installing a better restraint system would make any difference.

Stall/spin and inflight loss of control (VFR into IMC) accidents tend to involve a ground impact that generates a quick stop and very high G loads on the occupants, making most of those crashes unsurvivable. The reason: High G loads cause destruction of internal organs.

RLOC accidents more often involve speeds of less than 50 knots and an impact sequence that has the aircraft slowing to a stop over some distance—reducing the G load on the occupant.

The secret of survivability in an accident is to minimize the impact speed. One of the grim laws of physics is that force is a squared function—doubling the speed means quadrupling the impact. Hitting something as slowly as possible means the potential for survival goes up, which makes GA’s most common accidents the most survivable if the occupants are restrained.

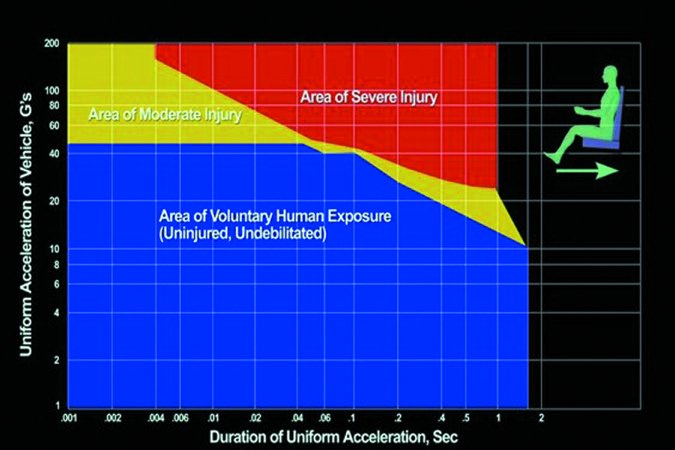

The chart above depicts the ability of a healthy human to withstand impact G loads straight ahead—toward the instrument panel—if properly restrained. The variables are the intensity of the load and its duration. If the G load on the occupant can be kept below about 10, the chances of surviving an impact go up dramatically, even if the impact sequence lasts some time.

The next factor in assessing crash survivability is the container holding the occupants. So long as it remains intact enough that the occupants don’t slam into it during the impact sequence, the chances of surviving go up. However, even if it remains intact, it’s still necessary to hold the occupant in position in the seat because the container isn’t very big—there’s not much “flail” space for the occupants.

That brings up the problem of a lap-belt-only restraint system. During an impact sequence of as little as one-G forward (toward the panel), it is impossible for the occupant to brace him or herself against the load and she or he jackknifes over the seatbelt. That means the head impacts the instrument panel or the back of the seat in front of the occupant, as shown by the photo at left of an impact sled test.

Head impact is likely to mean serious injuries. Even if the impact is light, it may be enough to stun or cause loss of consciousness that reduces or eliminates the occupant’s ability to get out of the airplane without assistance. That can be critical if a post-crash fire starts. In addition, jackknifing can cause spinal injury and paralysis.

A shoulder harness—even the most basic single-strap version—will help keep the occupant in place in the seat and greatly reduce the risk of hitting some portion of the interior of the airplane during a crash sequence, which is the cause of most injuries and deaths in lower-speed crashes such as RLOC.

That’s the analysis—shoulder harnesses will greatly increase the safety of your airplane. The real world agrees: FAA research shows 88 percent of injuries and 20 percent of fatalities have been eliminated through the use of shoulder harnesses over lap belts alone.

Conclusion

When your restraint system hits double digits in age, it’s time for replacement of the webbing. While buying new is an option, we think rewebbing is the sensible approach.

If any seat in your airplane doesn’t have a shoulder harness and it’s possible to install one, we strongly recommend doing so. We like inertia-reel restraints for their comfort when flying, but their price may dissuade owners from a retrofit. We think that the prices of fixed-belt three- and four-point systems are so reasonable that they should be the next upgrade an owner makes to her or his airplane.