The stars have aligned just right—your local airport has a waiting list for hangar space, you are unwilling to park your airplane at a tie-down and the airport has land it will lease at a reasonable rate. This is your chance to create a hangar that will suit your airplane—and potentially your need to spend quality time with your airplane.

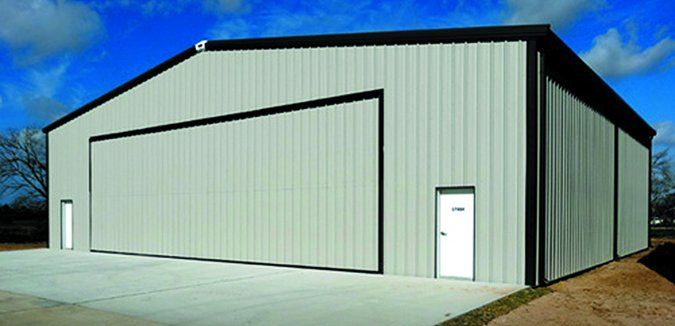

As we got into our hangar research we were amazed at the number of companies that sell pre-engineered hangars, many offering turnkey erection. Almost all are metal building manufacturers that build hangars as one of their clear-span products. Most will work with you to match the demands of your site and help you with what may be a complex approval process for construction on a public-use airport.

Early Considerations

Especially on public-use airports, we recommend that you do extensive homework regarding the airport’s friendliness to privately owned hangars. That starts with the airport’s Minimum Standards and its rules and regulations concerning hangars. We also suggest that you spend a lot of time talking with other owners of private hangars to find out about their experience in dealing with airport management.

On a private and/or residential airport, unless you are going to be the sole tenant, we recommend that you get to know other hangar owners, plus review any restrictive covenants and airport rules to get a feel for the atmosphere of the airport. We have seen big egos make life on little airports miserable for hangar tenants who don’t fit the mold.

We can’t emphasize enough the importance of making sure that you will be able to work with airport management—otherwise what starts out as a reasonably priced way to get into a hangar can turn into an expensive mess. We were recently apprised of the nightmare experienced by an aircraft owner who wished to erect a hangar on a state-owned airport. It took three years to negotiate the lease for the land under the hangar because the airport management company kept changing the terms and adding new conditions to the proposed lease.

Whether you are planning to build a personal hangar or a row of T-hangars to rent out as an investment, the first step is to sit down with airport management, outline what you intend to do and find out precisely what land is available, the cost per square foot to lease the land, the length of a lease the airport is willing to grant and what will be involved in obtaining taxiway access—plan on paying to pave any needed taxiway(s) and ramp(s) in front of the hangar(s).

Land Lease

In our informal survey we found that airports generally offer 25-year land leases, with one option to renew for a second lease period. We saw one that only offered a five-year, renewable land lease. We were told of a hangar owner at that airport who got sideways with the powers that be and was out on his ear when his lease was not renewed—ownership of the hangar reverted to the airport.

At the end of the lease, it’s not uncommon for ownership of the hangar to revert to the airport.

A lease shorter than 25 years may make it tough to get a loan to build a hangar of significant value. It makes the economics of amortizing an investment that will be worth zero at the end of the lease term less than attractive.

The lease should contain protections for you in that the airport should not be able to step in and take your hangar away from you for minor violations of airport rules or being a day late with a lease payment. In our opinion, the lease should require that the airport take steps akin to a bank foreclosing on a house for failure to pay for a mortgage. Airport politics can get weird, so it’s necessary to be able to protect yourself should someone with a lot of political clout and who wants your hangar start putting pressure on the airport manager to take it away from you.

Minimum Standards

Look carefully at the airport Minimum Standards (most public-use airports have them). They often have detailed hangar requirements, including minimum and maximum sizes as we’ll as, believe it or not, exterior color. Unreasonable Minimum Standards are a warning flag that the airport management will not be easy to work with.

Airport rules and regulations may affect hangar usage. We’ve seen some awful ones, such as the hangar door can only be open long enough to move an airplane in or out, no refrigerators or couches in the hangar and no parking a car in the hangar when the airplane is out flying. If you’re going to spend $50,000 to put up a hangar, you don’t want to be hamstrung in your enjoyment of it by petty rules established and enforced by unreasonable airport management.

Review the Airport Layout Plan (ALP). It shows existing facilities and projects usage of the airport into the future. Your proposed hangar may not fit with the ALP if the location you’d like is right where the airport intends to build another runway in 10 years.

Utilities

You may or may not be able to bring utilities to the hangar—if you can, find out what it is going to cost and if the airport has any rules relating to routing. We’ve seen airport rules regarding routing and burying electrical utility wires that made installment cost prohibitive.

Those who have built hangars told us that if you can bring water and sewer into the hangar, do so. Even if you can’t afford to put in a bathroom right away, the value add in doing so at some point will enhance the resale value of the hangar.

What are the taxes you will face in erecting and owning the hangar? Those can vary widely state by state and by locality.

There will probably be zoning regulations to comply with as we’ll as a local permitting and inspection process that will have its own set of fees.

Does the site drain adequately? Historically, airports have been built on the cheapest land available to the entity developing the airport. It’s not unusual for that land to have been cheap because it has crummy drainage. Building a hangar that turns out to flood easily is a mistake you don’t want to make.

Will the construction need FAA approval? On most public-use airports, you’ll need to file a Form 7460-1 with the FAA 45 days prior to construction. The FAA is concerned with structures that could project into protected airspace around runways or may block the view of portions of aircraft movement areas from the control tower. For most hangar construction, the requirement is a formality, although we have seen a few instances where the design of a proposed building had to be modified.

The Structure

Whether you are building a single T-hangar, box hangar or a series of either or both, you’ll need to decide on the basic structure. The most common is post-and-beam. You can still find Quonset/Nissen hut hangars. They are strong and inexpensive although, because they slope inward, take more square footage for the same aircraft storage area. The lower price may be offset by the cost of the land underneath. There are also durable fabric hangars on the market; however, we tend to think of them as temporary rather than permanent.

The post-and-beam structures are broken down to an open-webbed truss with straight columns and a rigid frame. The rigid frame uses tapered frame sidewalls (wider at the top than bottom) and rafters. The open-webbed truss uses straight sidewall columns that are much thinner than the tapered frame sidewalls and truss rafters. The open-webbedtruss has a substantially smaller wall width, giving more space inside the hangar and allowing a larger door for a given overall hangar footprint.

Hangar Doors

Doors make the hangar. There are three main styles in ascending cost: sliding, electric bi-fold and one-piece hydraulic lift.

Sliding doors either have rollers on the top and are routed by a series of metal guides on the floor, or have rollers on the bottom on an embedded track and door guides at the top of the opening. We have spent hours trying to open or close sliding doors in snow country.

We once watched an owner try to open his sliding hangar door by pushing it with the front bumper of his car. He damaged the door and bumper—and didn’t get the door open. We blew a tire on our car by driving over a floor-mounted door guide at the wrong angle.

Sliding doors require a good foundation as the freeze-thaw cycle and heaving of the ground often causes them to bind.

We’ve also seen poorly designed hangar systems in which opening the sliding doors of one hangar covered the door to the next hangar, effectively blocking it. Finally, we recommend against outrigger-type sliding doors (previous page) in snow country.

The electric bi-fold hangar door leaves sliders in the dust when it comes to convenience. Even though the door is more expensive than sliders, it does not require the foundation work of a sliding door. Of course, it’s necessary to have electricity available, so an inability to run utilities to the hangar may preclude an electric door unless a generator is available.

Electric bi-fold doors are attached either to the header system of the hangar, door truss or door frame. When closed it latches to the vertical door columns—either automatically or manually. Because an open bi-fold door forms a wedge that subtracts three feet from the vertical portion of the door opening, it may requiring building a taller hangar than needed for other doors.

Considerations when picking an electric bi-fold door include whether the company that makes the hangar also makes the door—which simplifies construction and warranty work; the location of the motor, gear box and drive system—we’ve seen some that were stupidly located where they partially blocked access through the human door; the location of the control panel (we don’t want to walk across the hangar to turn on the lights); safety factors in the door system and safety factors built into the lift cables or straps—they will eventually fray.

Make sure you see one of the doors installed before you buy it: We’ve seen some poor bi-fold installations that looked good on paper. In one, when the wind was blowing against the door, it was necessary for the operator to push the door outward against the wind with all his strength before hitting the door open button. Otherwise, the system wasn’t strong enough to start the door moving against the wind and the circuit breaker would pop. The circuit breaker was located just below the ceiling of the hangar, necessitating climbing a tall ladder and using a stick to reset the breaker.

Hydraulic Doors

We found two major suppliers of single-piece, hydraulic doors: Schweiss (which also makes bi-fold doors) and Higher Power Doors. While more expensive than a bi-fold door, they allow a shorter door opening because they do not create the wedge of a bi-fold door when open.

We like that the Higher Power door mounts in its own support frame, eliminating the need for a truss or header to support it on the hangar itself.

An open hydraulic door provides a large shaded area in front of the hangar; however, as it sweeps forward while opening, it requires that the airplane be parked farther from the hangar when the door is operated than with other types of doors. It also may require removing a significant amount of snow before operating.

While researching this article, we looked at hangar rental prices, only to find that they vary wildly by location—the busier the airport, the more expensive—the type of door installed and availability of electricity. We saw monthly rates for T-hangars from a low of $150 to a high of $750. We did not find many box hangars for rent.

We explored the cost of constructing a 40-foot x 40-foot box hangar and got prices for a pre-engineered structure with a bi-fold door starting at $28,000 for the Summit S-2 hangar—a larger, more sophisticated version of the Summit S-1 described in the sidebar on page 18. It is designed to be erected by the buyer. The price does not include the concrete floor, footings, electrical connections or any other desired add-ons.

Overall, we think $40,000 represents the base price of a turnkey 40 x 40 box hangar with bi-fold door.

When looking at building a group of hangars, we like companies that specialize in pre-engineered hangars and have been around for several decades such as Summit and Erect-A-Tube (www.erect-a-tube.com). We note that Erect-A-Tube was a pioneer in developing the bi-fold door. Nevertheless, after following the construction of two large box hangars over the last few years, we have been impressed with the ability and competency of the companies that offer pre-engineered hangars as one of their metal building product lines.

Summit S-1 Safe-T-Hangar: Portable

For the owner who wants a strong, no-frills hangar to protect his airplane and is handy with tools, the Summit S-1 Safe-T-Hangar may fit the bill. Summit Metal Systems advertises its S-1 by simply saying that if you’ve got ramp space, it’s got a hangar for you.

For about $19,000, before shipping, Summit will put together what amounts to a sophisticated Erector Set that you put together on your ramp space. Although it’s designed for installation on concrete or asphalt, a hard surface is not absolutely required—just a way to anchor the structure to withstand wind loads expected for the area.

To give an idea of the strength and ability to handle snow loads, Summit’s website shows an S-1 hangar with a pickup truck parked on top of it. We’re not sure how they got it there, but it was an effective demonstration.

According to Summit’s Mark Lutman, most pilots have the necessary mechanical ability to put an S-1 together, as the company has tried to make them as user-friendly as possible. Summit personnel are ready to field questions that may develop as a first-time hangar assembler works her way through the process.

The hangar is 41 feet, 6 inches wide and 33 feet deep. It consists of a 20-foot-wide center section that has a door clearance of 10 feet, 10 inches and two shorter wing sections with doors that are 10 feet, 10 inches wide. The photos below are of an earlier version of the hangar, but give an idea of the size of the S-1. The aircraft in the hangar is a Cherokee Turbo Arrow—as can be seen, there is plenty of room for the airplane and guests at a cookout.

The hangar itself is a steel frame with sheet metal sheathing. The side doors slide open against the inside ends of the hangar while the one-piece center door lifts up much like a one-piece garage door with a spring-assist.

We were told that owners have installed electric garage door openers on the center door, but our experience has been that so long as it gets a modicum of maintenance and lubrication, the forces involved with opening and closing are reasonable. Lutman told us that Summit does not recommend installing garage door openers.

Summit advertises that it will work with prospective buyers with site planning and erection of the hangar. Having been in business for some 20 years, it has significant experience with airport leases, subleasing and renting for those who wish to assemble several of the hangars to rent or lease to aircraft owners and will work with buyers on addressing those issues.

Summit advertises the S-1 as a portable hangar. While portable means disassembly rather than picking it up and moving it, we agree with the term. We are aware of circumstances in which the ability to disassemble and move a hangar saved the hangar owner a great deal of money. While rare, if you feel the need to own a portable hangar, the S-1 should fit the bill.

A Successful Example

One of the two hangar projects we followed was in Cadillac, Michigan, where Northwoods Aviation replaced its hangar, which had originally been built by the WPA in the 1930s, with an 80-foot x 60-foot pre-engineered hangar from Wick Building (www.wickbuildings.com). It included a 50-foot-long Schweiss bi-fold door.

Wick sent an engineer to Cadillac to coordinate soil analysis, site survey and evaluation of heating needs for the hangar. That resulted in engineering drawings that were easily accepted by the airport authority.

Because door height was vitally important—the hangar would handle airplanes on amphibious floats—Northwoods owner Derek DeRuiter specified that the hangar be engineered to allow the bi-fold door to be mounted high on the door truss so the bottom of the door in the open position matched the top of the door frame.

A team of builders contracted through Wick erected the hangar. We visited periodically during construction and spoke with DeRuiter a number of times. He did not express any complaints with the process to us. With in-floor heat, a ceiling crane for lifting airplanes off and on floats, insulation for the north woods and a number of options for his specialized business, the finished cost was we’ll north of $200,000. Coming out of the first year of operation and a Michigan winter, DeRuiter told us that he has been very satisfied with the result.

Conclusion

We recommend caution going into construction of a hangar on a public-use airport and constantly keeping an eye on your personal cost-benefit ratio during the design phase. We do not recommend considering the hangar as an investment other than in protecting your airplane and providing a comfortable place to spend time while at the airport. As general aviation continues to struggle, we are not optimistic on hangar resale value.

Nevertheless, as a result of our research and following the construction of two hangars, we are optimistic about the quality of pre-engineered buildings and doors available. If building a hangar is right for you, we think you can find a pre-engineered hangar that fits your needs.