The light sport market is supposed to be about simple, affordable and fun flying, isn’t it? While a handful of models come close to hitting that mark, including versions from Legend Aircraft, Cub Crafters and now, SAM Aircraft with the SAM LS, CC and STOL models, it’s the affordability thing that always seems to get in the way.

At $131,000 delivered, the SAM LS may not represent the affordability that the light sport market once promised. On the other hand, owners who want a modern aircraft that has the retro appeal of vintage trainers from the Golden Years might tolerate the SAM’s price tag. Want to save some dough? You can build your own.

Retro Vision

SAM Aircraft was established in Canada in 2009 by Thierry Zibi, an enthusiastic pilot who set out to design a modern and comfortable sport plane that has the charm and interesting ramp appeal of a model from the 1930s. In our view, he’s succeeded because in the two days the aircraft spent on our ramp, it attracted huge amounts of attention. Some thought it was a replica of a Ryan STA (from which it was inspired) while others called it a Varga Kachina. Whatever, it’s an attention-getter.

Savvy folks will recognize that the model we flew was equipped with a tricycle landing gear—an odd configuration for its retro-wannabe fuselage. Still, the aircraft can be ordered with a tail wheel.

Three Wings

Zibi’s other goal was to produce an aircraft that can be personalized. Aside from the choice of landing gear, the aircraft can be ordered with one of three different wing configurations. This includes the SAM CC (25-foot wingspan), the SAM LS (28-foot wingspan) and the SAM STOL (32 foot wingspan).

No matter what wing or landing gear you choose, the tail and the wing center section is common between all models. The aircraft we flew was the LS model, with a wing that’s stressed for up to 4G of flight load at the 1320-pound gross weight (the maximum takeoff weight allowed under LSA certification). Basic empty weight is 830 pounds, leaving 490 pounds of useful load.

A few words on certification; the SAM is currently undergoing LSA certification and is already certified in Canada under AULA (Advanced Ultralight Aircraft) regulations. As we explain in the sidebar on page 5, the aircraft is available as an amateur-built kit.

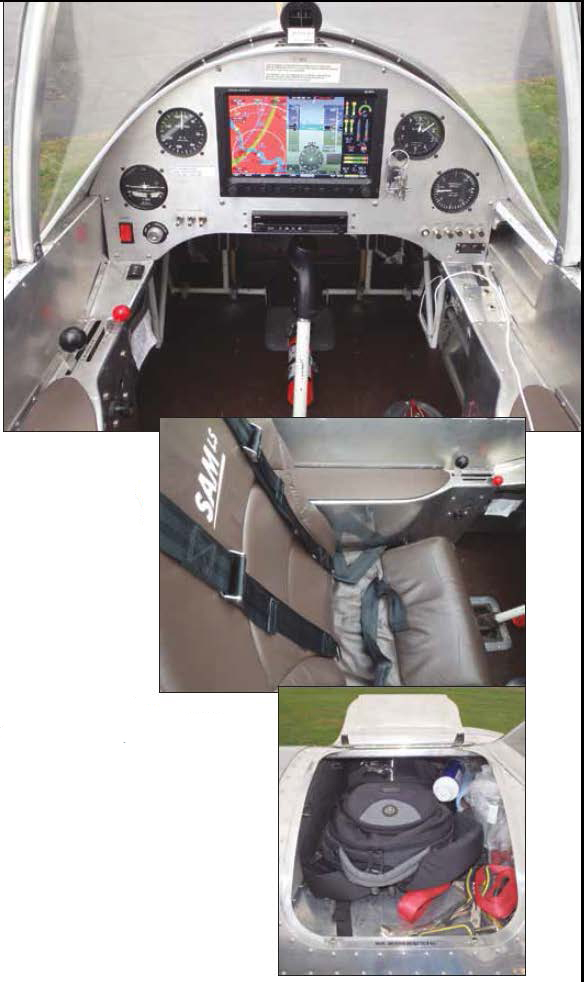

The tandem-configured aircraft can be ordered and flown with or without a canopy that’s easily removed and reinstalled with three quick-release hinges. Once inside, cabin width at the shoulders is 26 inches and has adjustable leather seats and armrests. There’s little if any room for storage once seated—not even a small camera bag, as we learned (unless you place it on the empty rear seat). There is, however, a small storage area just forward of the windshield that’s accessed on the outside of the aircraft. It can accommodate up to 35 pounds of stuff. There’s also an optional aft baggage area, at a weight premium.

While the aircraft is intended to be flown from the front seat, flying from the rear seat is easily accomplished (we tried it). The rear position has a throttle, stick and rudder pedals, but passenger brakes are optional. Both seats are adjustable over a long range—the SAM accommodates pilots of all sizes.

Still, we were barely able to access the rudder pedals in the back because they’re oddly surrounded by narrow tunnels that are crudely fabricated from unfinished sheet metal. Passengers with larger feet will struggle to fit them in the tunnels (size 10 hiking boots barely fit). Zibi basically said the sheet metal surrounding the pedals are intended to keep the passengers’ feet from kicking the pilot in the rear end. Fair enough.

Zibi also said that rear-seaters will be subjected to sizable amounts of wind blast, so without a second windshield, open-canopy flying in the back will require a helmet and goggles—just like the old days.

rugged

Efficiency

Front and rear-seaters are protected by a 4130 steel protection cage that absorbs structural loads while attaching to the aircraft’s aluminum bulkheads. All control surfaces are aluminum, and the fuselage is made of 2024 and 6061 aluminum. Wing load limits have been tested to 5.2 positive and negative G.

Each wing contains an 11-gallon fuel tank, for a total of 19 gallons of usable fuel. The tanks are in the central portion of the wing, just aft of the solid, riveted main spar. Managing the fuel is simple—select left, right or off on the fuel selector that’s located on the right side of the cockpit. The fuel return line is connected to the left fuel tank, so if you plan on using all of the available fuel, you’ll want to spend the right tank first. Otherwise, burn from the left tank first, to make room for returned fuel.

The dual-carburetor, 100-HP Rotax 912S that was installed in the SL we flew has an engine-driven fuel pump and an electric boost pump. Zibi said the aircraft can accommodate a Lycoming IO-233 engine, but that will require a shorter engine mount than the longer frame that’s used to support the Rotax. In fact, the Rotax engine mount extends the engine we’ll forward of the firewall, creating a maintenance-friendly environment. It also keeps the CG forward. The cowling is so large, distant onlookers think it’s holding a rotary engine, instead of a small Rotax. There’s that nostalgia factor, again.

For certain, the Rotax 912S is efficient, burning 4.5 GPH at 5200 RPM in cruise, yielding a 480-mile range. That’s a tad over four hours’ endurance—probably more time than most would want to spend in the airplane in one sitting—despite the reasonably comfortable leather seating.

Maximum cruise speed is 125 MPH—a number we didn’t see—because the aircraft we flew had a temporary Sensenich wood propeller, subbing for the original that was out for repair. The standard propeller is a ground-adjustable 70-inch diameter composite Sensenich that, according to SAM, climbs the LS at 800 FPM. That’s a respectable number.

AVIONICS

The front cockpit of the SAM looks nothing like any you would find in a 1930s monoplane. Slide into the leather seat and you’re greeted by a 10-inch Dynon Skyview color display with integrated GPS, terrain alerting, advanced engine monitoring—including fuel quantity—and an integrated transponder. There’s also synthetic vision. The SAM we flew had Garmin’s SL40 communications radio that’s been replaced by the new GTR-series radios.

To back up all of the glass, there’s analog airspeed, altimeter, vertical speed and turn coordinator instruments, plus a wet compass. A 7-inch Dynon Skyview display for the rear cockpit is optional.

Flying It

You board the SAM forward of the left wing’s inboard leading edge, with a step that hangs off the fuselage. Once on the wing walk, simply step onto the seat and plop down—fighter style.

The front and rear seats have three-point harnesses (we expected a four-point design). When going flying with the canopy installed, grab hold of it and lower it down into place to catch the securing hooks and a latch that locks into place. This latch can be opened from the inside and outside of the airplane. To open the canopy, lift the latch and pull the canopy backward one inch, then tilt it from left to right. The canopy provides good visibility while seated in the front or in the back of the aircraft.

For those not familiar with starting a carbureted Rotax, it’s easy. Electric fuel pump on, throttle at idle, choke on and turn the key. With the Rotax running, the cabin is surprisingly quiet, with little airframe vibration other than a brief canopy shake until the Rotax comes to smooth idle power. As part of the standard avionics package, a two-place intercom is installed.

The SAM is a tall aircraft, resulting in good visibility during taxi, while the nosewheel steering provides plenty of feedback once you get up to taxi speed. Before takeoff, there’s not much to do with the Rotax other than throttle up to 4000 RPM and perform a magneto check.

The takeoff is accomplished with the Fowler electric wing flaps retracted. The 100-HP Rotax quickly brings the aircraft to its 65 MPH rotation speed, resulting in a 350-foot ground roll. Zibi says the aircraft doesn’t have limitations for taking off and landing on turf runways.

If trimmed properly, the aircraft is easy to coax off the runway, although you’ll need to immediately lower the nose to keep it flying (it’s no Cirrus). Once it is flying, the drill is to transition to a 75 MPH cruise climb, where you’ll immediately enjoy the aircraft’s pleasant flying characteristics.

The flight controls for pitch and roll consists of a combination of bellcrank and pushrods, while the rudder is controlled via cable. There are considerable amounts of pitch stability and control authority, thanks to a large and efficient horizontal stabilizer, with 20 degrees of travel in both directions. That said, the aircraft lets you know when it’s out of trim in the pitch axis, with noticeably heavy forces on the control stick that are corrected with the electric pitch trim system (commanded by a rocker switch on the control stick).

The roll stability in this aircraft is pleasant. We were throwing the SAM around the sky at steep bank angles and experienced little adverse yaw, even with feet off the rudder pedals. Stick forces in roll are light. The Frise ailerons keep the aircraft tracking precisely where you put it, even with hands off of the controls. The aerodynamically balanced vertical stabilizer extends to the bottom of the fuselage, providing decent yaw control.

Stall speed in a clean configuration is 49 MPH and 42 MPH with full flaps (35 degrees). The SAM exhibited no bad habits in a stall, with a noticeable buffeting followed by a drop of the nose, and no wing drop. The aircraft quickly flies out of the stall when you pitch it down. There’s more stall warning with the flaps down, with a buffet occurring a few MPH prior to full stall and again, no wing drop. The aircraft had acceptable roll control in a fully stalled condition.

At the time of this review, the aircraft was being tested for its spin characteristics (we opted out of being part of that testing). Zibi told us the vertical stabilizer design is paying off, based on the spin testing to date.

“The aircraft really doesn’t spin but instead, it’s more of a spiral, rather than an aggravated stall. We’re finding that even in a cross-controlled situation, the aircraft is easily recovered,” Zibi said. Since the aircraft is currently certified in the AULA category, aerobatic maneuvers are off limits.

For landing, you’re shooting for a 90 MPH initial flap extension speed. In a descent out of 3000 feet, the aircraft hustled toward Vne (155 MPH), so you’ll need to be vigilant in minding pitch and power control going downhill and for slowing to flap speed. Maneuvering speed at maximum gross weight is 90 MPH. Ideally, you’ll want an approach speed somewhere in the 70 MPH range. We flew the SAM in relatively calm surface winds, but the operating handbook lists the maximum demonstrated crosswind velocity as 13 knots, based on a 1232-pound gross weight. Manage the airspeed and flare properly, and a tricycle gear-equipped SAM will reward you with a nice landing. Misread the sight picture—as we did on the first landing—and the main telescopic gear is rugged enough to sustain drop-ons, as long as the aircraft is tracking straight.

Fun to Fly

That can be said of many sport planes that are on the market and it’s true of the SAM, too. Buyers might be attracted to the heavy-duty structure, leather seating, removable canopy and the other creature comforts that the SAM brings to the table. The reality check, however, is the $131,000 price tag and the pending LSA certification. With full fuel, a well-equipped SAM has a useful load in the 500-pound range, when obeying the 1320-pound gross weight limit. Depending on the mission, this might be fine for some. For others, maybe not.

As for the price, we think it’s fair, based on equipment, build quality and the SAM’s cool factor. On the other hand, its price point is shared with other respectable and interesting factory-new models, including the closed-cowl Legend Cub and Lightning LS-1, to name a couple.

Contact: SAM Aircraft – 514-445-6409 – www.sam-aircraft.com