Modifying airplanes that the original manufacturer got almost right has been a constant in general aviation. But lately, we call it something different: remanufacturing. And if any company is the Alpha dog of this process, it’s Cleveland-based Nextant Aerospace, which has had impressive success remanufacturing Beechjet 400As. Now it’s poised to repeat the trick with the popular King Air C90 series.

It’s no accident that Nextant has concentrated on Beechcraft products. The company is looking for durable, over-engineered airframes manufactured in relatively large populations. Both the 400A and certainly the King Air qualify, even if Nextant is picky about what airframes it will rework.

When pushed into Nextant’s hangars at Cuyahoga County Airport, hard by Lake Erie, the airplanes are decade-old hydromechanical stalwarts with steam gauges. About 140 days later, they emerge as nose-to-tail remans with the latest digital technology that even bests what the factory might offer. Given the prices, the economics are compelling enough that the industry is feeling Nextant’s influence. We recently visited the company’s works to get a feel for the emerging King Air project.

They Fly These Things

Nextant is nestled amongst a group of companies under a parent called Directional Aviation, a closely held company managed by CEO Kenn Ricci. All of the operating units—there are nine—are aviation related and juxtaposed to create what might be ideal synergy for remanufacturing airplanes. Directional’s portfolio includes two fractionals—FlexJet and Flight Options—two charter companies, an aircraft sales outlet and three maintenance organizations. This mix of companies evidently led quite naturally into the Beechjet 400A project. “We operate 90 Beechjet 400As between FlexJet and Flight Options. So we knew what these airplanes are capable of and what it requires to maintain them,” says Kent Stauffer, Nextant’s VP of operations and customer support. The 400A has a reputation for being fast and robustly built and readily maintainable into the future, despite being out of production for more than a decade, if not longer. But it has warts, too.

The Pratt & Whitney JT15D-5 engines are considered old technology and even the latest versions of the airplane have analog gauges and dated avionics. Nextant sales and marketing VP Jay Heublein describes the 400A’s original engine mount pylon as “a mess” that caused vibration and cracking in the horizontal stab and had poor thrust delivery and aerodynamics.

Much of Nextant’s developmental effort focused on reengineering the engine pylon and fitting more efficient, high-bypass Williams FJ44 engines. Moreover, the airplanes are stripped to bare metal, rewired and replumbed, repainted and upholstered and given new Collins Pro Line 21 avionics. They emerge from the rebuild as near-new fully digital airplanes that merit the ultimate recognition: An Aircraft Bluebook value line that marks them as a new model year.

If anyone doubted the business sense of Nextant’s template, the numbers should allay them. When we visited last October, the company was about to deliver airframe number 60 and the King Air project, called the G90XT, was ramping up.

Why King Airs?

While other companies have tended to gussy up older airframes with paint and avionics, Nextant pursues a cannier philosophy. “In our space, what we’re looking to do is find airframes that are over engineered or have the capability to apply design improvements that are still sustainable in the future,” says Nextant’s Stauffer. “For example, the aerodynamics of the airframe have to be conducive to improving upon it; you can’t simply take an old outdated airframe and make it new again,” he adds.

Nextant found this in the Beechjet 400A with the aforementioned reengining and pylon redesign, something largely made possible by computer-aided design analysis that didn’t exist when the airplanes were originally designed and that Beech lacked the resources to apply as the model matured. The King Air C90 series meets the same design brief.

Despite being a 50-year-old design, it’s still in production with about 20 to 50 units sold each year. (The larger 350 is the King Air current best seller.) Nextant—and King Air owners—like the fact that the model has a reputation for rugged maintainability and over engineering at every turn. That explains, says Heublein, why there are more than 1600 examples in the field that Nextant can mine for remanufacturing. As a test case to prove the concept, the C90 that Nextant used as its test bed is the oldest, highest-time King Air the company could find that it would consider for remanufacture. With four years of 400A rework behind it, Nextant had a clear picture of how to upgrade the C90.

“When we look at airplane design, everything has to buy its way onto the airplane in a couple of categories,” says Heublein. “One is, will it significantly impact the overall safety of the operation? And it has to significantly affect the operating cost to the positive. It’s got to increase dispatch reliability or decrease maintenance costs. If it doesn’t do those things, we’re not necessarily going to bring that technology onto the airplane,” he adds.

Specifically on the G90XT, Nextant’s design plan translated into new engines and reworked nacelles, new avionics, pressurization and environmental systems and, as with the 400XTi, a complete redo of wiring, plumbing and paint. The result, Nextant predicts, is an airplane that will climb faster, cruise higher and faster and carry a little more than new C90s emerging from the factory in Wichita, all for a lot less money than a new airplane costs.

The big-ticket item is reengining, replacing the venerable Pratt & Whitney PT6A-135 with the GE H75, a powerplant that both GE and Nextant claim is more thermally robust, more efficient and less maintenance hungry than the Pratt. (See the sidebar for details on the engine.)

Down to the Nubbins

When we were walking the production floor with Kent Stauffer, he said that during its remanufacture process, the airplane will be revealed in more intimate detail than at any time since it was built. That might be an understatement. As it did for the 400As, the King Air remans will be completed in four steps using Nextant’s cellular approach to manufacturing. The airplanes stay put in the hangar, but work teams cycle from airframe to airframe, completing each stage.

Nextant calls the first step deletion, in which all of the old equipment and wiring is removed, with about 90 percent of it replaced. The aircraft are given an invasive inspection in search of damage or corrosion which is repaired using either OEM parts or Nextant’s own PMA components. (It has more than 2000 PMAs and its own Beechcraft parts network.)

In both the King Air and 400A, we saw interiors stripped down to the inner hull with fresh harnesses in place, all prepared in Nextant’s wire shop. Nextant also has a metal and machine shop and, on another site, an interior shop.

“In-house or in the group, we have a company that does everything except paint,” says Stauffer, and even that is about to come in-house, making Nextant one of the most vertical companies we’ve seen. Stauffer said keeping the work inside improves scheduling, controls costs and maintains quality. If Nextant reaches the same volume in the G90XT as it has with the 400XTi, production control may be more critical than ever and we suspect there will be some physical expansion. The hangars were nearly full when we visited.

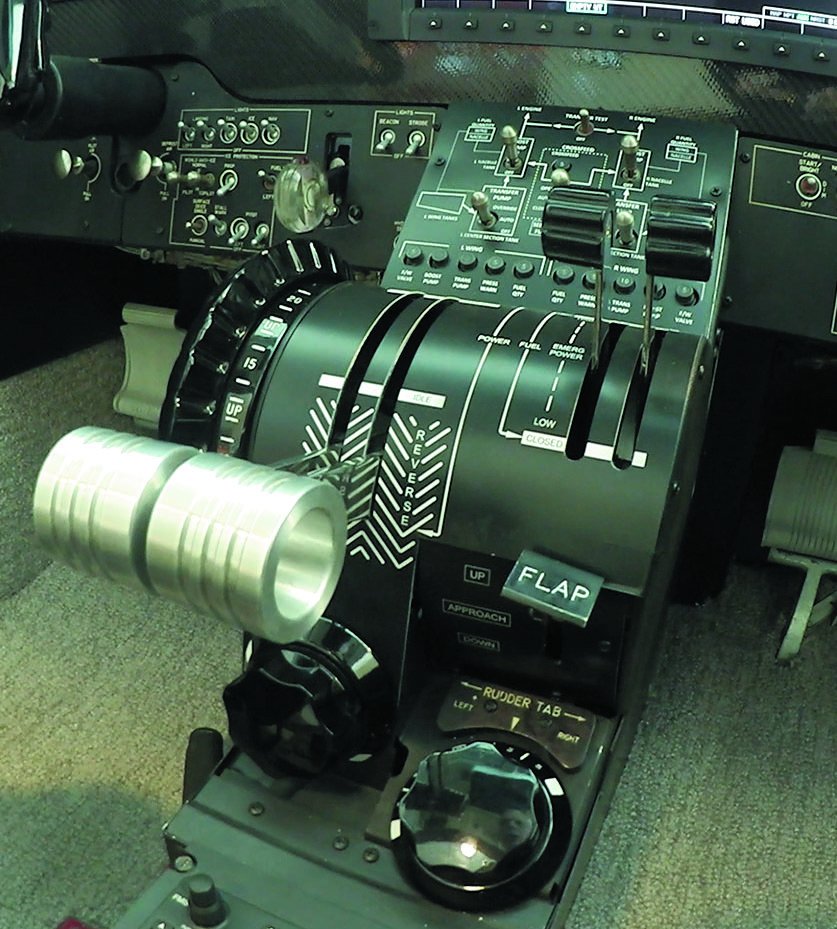

In addition to the engine change and nacelle modifications, the G90XT gets a full avionics remake with a Garmin G1000 and GFC 700 autopilot. It also gets new environmental equipment. “One of the biggest complaints we hear from King Air owners is about the air conditioning,” says Stauffer. “The two-zone Freon system we install will cool a heat-soaked cabin to 70 degrees in two minutes,” he adds. Nextant claims its environmental system, including digital pressurization control, bests the factory system being installed on new King Airs.

They make a similar claim about their version of the Garmin G1000. The fuel system is fully integrated into the G1000. “No one had ever done that before. That gives us an advantage because even the new airplanes have 1960s technology for fuel management,” says Heublein.

Performance, Price

When we visited, the G90XT had completed certification testing, but final approval was still at least a week away, so we weren’t able to fly the aircraft. Nextant hasn’t released final performance data, but Heublein says initial data shows that even though the engines are a bit heavier, as is the air conditioning, so much weight is removed from the old aircraft in avionics that the airplane should pick up a slight payload bump. The weight removal also helps the airplane’s tendency toward a forward CG.

The larger gains, according to Heublein, will be in flight performance.At 550 HP, the H75 is substantially derated mainly because of airframe limits. Because of its surplus thermodynamic margin, the G90XT will be

capable, according to Nextant, of climbing faster and cruising both higher and faster where the PT6A tends to be temperature limited, especially on ISA-plus days. It also has a single-lever power control thanks to the limited-authority engine control GE developed. That means the pilot doesn’t have to worry about temperatures during starting or climb, but merely advances the throttle for more power and yanks it back for less. Two condition levers are retained as backup for the electronic controls. In normal operations, they shouldn’t be needed.

Heublein thinks the engines’ non-temperature-limited performance will translate to 15- to 20-knot higher cruise speeds at altitude, 20 percent faster climb and 10 to 12 percent reduction in fuel burn. If this data proves true, those are killer numbers, in our view. We’ll find out when we’re able to fly the airplane.

Nextant is bringing in its 400XTi at a little more than half the price of the closest competition, which it considers the Embraer Phenom 300 or the Citation CJ3. Heublein told us the typical 400XTi invoices for a just over $5 million, while the new jets in the same market space sell for between $8.3 million and $9.3 million.

On the King Air side, Nextant says the G90XT will sell for between $2.3 and $2.4 million if the customer supplies the airframe and between $2.8 to $2.9 million if Nextant sources the airframe. According to Textron’s price list, a new King Air G90GTx retails for about $3.9 million, so Nextant’s G90XT represents a savings of $1 million to $1.6 million against a new model. That’s a big number, to be sure, but not half price. This makes us wonder if Nextant’s business on this project will tilt strongly toward owners who already own King Airs and would like to upgrade but can’t see the point of buying new just for the same performance. Heublein and company are counting on it.

“That was the thesis for the company in the first place. We absolutely think the largest percentage of the market is going to think the way we think. This represents a great value proposition. I get that the metal isn’t perfect. But we looked at it this way, even if we lost 25 percent of buyers because they’re saying ‘I want new metal,’ the market is still enormous and the business case is, too,” Hueblein says. He was proven correct in the Beechjet market. We’ll see if the same is true for King Airs.