Lets sa

As we reported in the September 2007 issue of

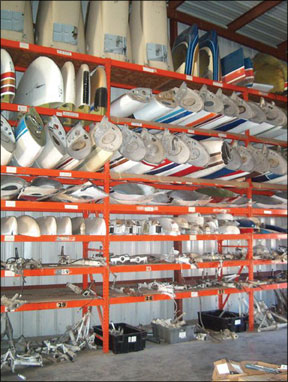

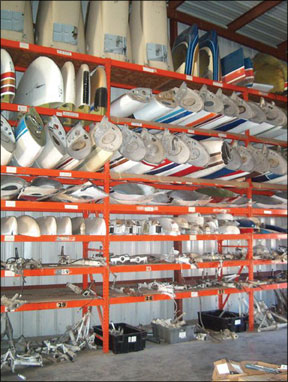

Aviation Consumer, finding replacement parts is getting to be an expensive chore. Often overlooked, particularly by owners, is the option of buying a used part from an aircraft salvage

yard. Around the country, there are dozens of small and not-so-small businesses that deal in recycled airplane parts.

The list of salvage-part benefits is encouraging. The parts are made to fit, theyve already been tested, theyre already airworthy and legal and theyre ready to ship. Best of all, they cost half (or less) the price of a new part.

The downside is that theyre used and sometimes show it, they need to be inspected and may need some repairs or cosmetic work, depending on price. And you usually buy them sight unseen, so what you don’t see is what you get anyway.

How it Began

Aircraft salvage is an interesting industry. The modern version of it basically began in the 1950s, started by three entrepreneurs with a great deal of foresight and no small degree of business acumen. These were Terry White, Alan Paulson and Bill Duff. White and Duff are still in the business and are located in Bastes City, Missouri, just outside of Kansas City and Denver, Colorado, respectively. Paulson dealt mostly with larger aircraft and airliner parts and was based in California. “We started at the right time, what we call the golden age of aircraft salvage. Its changed a lot since then,” Terry White told us.

Salvage is also a huge industry, requiring equally large doses of capital, patience and savvy to actually make money. And like aviation itself, the salvage industry has changed significantly over the years and it continues to evolve.

In the old days, salvage usually meant an airplane was damaged and the insurance company would estimate the cost to repair versus the recovery of totaling the piece and selling it to a bidder. In a nutshell, here is how the industry worked: Bids were sent to salvors registered with the particular insurance company. Things like cause of accident, time on the airplane, registration number, avionics and location were given. The salvors then had to determine the value of the salvage, either by inspecting it personally, finding someone locally who knew airplanes to take photos, or getting a description of the piece over the phone.

The wholesale value of the airplane was determined through the

Aircraft Blue Book

and the salvor would bid the salvage based on what they thought they could sell within a month, usually the engine and avionics, factoring in the retrieval costs, what parts were hot and what they had to store for months or years.

Naturally, the bidder with the most savvy and who knew what questions to ask about the equipment or systems and knew what normally happened to an airplane in a particular damage scenario would win the bid. Bids were submitted by Telex back then and the winner was notified the next day.

In the 1980s and 1990s, airplane values skyrocketed after Cessna and Piper ceased production. Salvage parts prices followed. Cessnas and Pipers primary income was building parts and to cover their monthly nut, these prices escalated. To keep airplanes flying and to make big bucks, the rebuilding business began to boom. A mom-and-pop industry began to develop, usually people who signed on as salvors just so they could buy an airplane to rebuild or for the parts to keep their personal airplane flying.

This had a dramatic effect on the industry. Neophytes bid salvage way too high either because they were buying emotionally or had to have the piece for parts. Salvage that had formerly sold for $1500 was climbing past $4000 to $5000. The established shops suffered sticker shock and began declining to bid on smaller items.

The claims companies recognized this and had no real devotion to the established companies, so they sold to the highest bidder. This muddied the waters even more, with many bidders being undercapitalized or unable to retrieve the salvage. But the damage was done.

Online Bidding

As the Internet matured, insurance companies began posting salvage for all to see and bid on. They began including detailed information on the salvage as simple marketing took over. This created a bidding frenzy and the established salvors, with the infrastructure and capital to follow through, began avoiding smaller pieces or bidding them out of courtesy, increasing their bids on lots of multiple airplanes or inventories, or on larger cabin class, pressurized turboprop or turbofan aircraft.

While it might initially seem that this would hurt the larger buyers, it in fact helped them. Bigger, more expensive aircraft meant higher salvage costs, but it also meant that the profit on one aircraft was many times that of buying smaller pieces. While

hauling in a King Air or a Citation is more difficult than a Cessna 172, it isn’t that much more expensive and one engine is worth $50,000 or more, compared to the Lycomings $5000 to $9000 sticker.

Similar economics applied to airframe parts. For example, a Citation pilot-side windshield is listed at $90,000 new and could take months to obtain from Cessna. An airworthy part from a salvage yard would cost 50 to 70 percent less and you could get it in three days.

White told us something surprising. “We actually buy more flying airplanes these days. Many are flown right into our strip by their owners,” he said. Even if such an airplane was totaled because of severe hail damage, internal parts are usually in excellent condition.

Good Parts?

While some owners are concerned about using a salvage part, particularly on higher performance aircraft and jets, there really isn’t much cause for concern. First, the

legality of the part, both its integrity and application, is determined by the holder of an IA. The FAA isn’t concerned that a part comes off of a damaged aircraft, only that it be inspected according to the FARs regarding that particular part and the damage incurred and that it be approved for return to service.

Realistically, any part thats installed becomes used. The biggest deterrent to using a salvaged part is the emotional stigma of having been part of an accident or, God forbid, a fatality. Superstitious buyers actually do stay away from some of these, but most buyers never know where the part comes from.

A paperwork trail is usually available, listing the aircraft from which the part originated and the parts seller can often give pertinent times on the total airframe and/or engine. If you know the N-number and are concerned, the FAA will provide a copy of the aircrafts known manufacturing and maintenance information for a small fee. Most modern parts have a part number or some sort of ID imprinted somewhere on the part that doesnt get painted. The installer takes care of the rest.

Liability is a major concern of most salvage companies. As they usually have deep pockets, they try to defer this liability to the installer. Some parts they sell are pristine and others may have some damage, whether structural or cosmetic. This is reflected in the price of the part. Some parts are so rare or expensive from the factory that mechanics or shops will factor in a repair or overhaul.

White Industries, for example, will describe a part over the phone or occasionally take a digital image and send it to the customer. They will remove the part and wash it, but will do absolutely no repairs. The mechanic will inspect and determine if any repairs are necessary and then prepare the part for installation. Expect to have to paint every airframe part since even the whites are worlds apart. White Industries also doesnt warranty a part, rather they offer a 30-day refundable period.

Radios, Engines

The most popular parts requested from salvage yards are avionics and engines. Avionics can be used in any airplane and engines are common to a number of designs. Salvors handle sales of these items differently, depending on their experience or capabilities. For instance, White Industries only sells avionics to shops or dealers. Theyve had bad experiences selling to aircraft owners or mechanics because of returns or installation issues. Its simply easier and just as profitable for them to sell to a shop that can test and repair the piece.

One of the leaders in the avionics department is Wentworth Aircraft, who is notably the largest single-engine Cessna and Piper salvage yard in the country, according to a couple of adjusters we know. Started by Steve Wentworth and his father, Chuck, when pop needed parts for his Cherokee, these two auto salvage guys quickly embraced aircraft salvage and today are a large concern.

They elected to forego bidding on all brands and large aircraft and instead focused on singles, notably Cessna 100 and 200 series airplanes, Pipers and Bellanca Vikings. This is because Cessna was the most popular aircraft and Wentworth owned Pipers and a Bellanca Super Viking. When he began flying a Mooney Bravo a couple of years ago, he also began buying Mooney parts. “Besides being in the business, a guy likes to have spares,” Steve Wentworth told us.

As big companies dwindled and salvage prices climbed, Wentworth soon found that they were being awarded more and more Beechcraft equipment bids, particularly Bonanza and Baron salvage. They also own a number of Robinson helicopters.

Over the years, theyve occasionally purchased other brands and more recently have become the top buyer of Mooneys and Beechcraft Bonanzas and Barons. They are located in the Minneapolis area and the company has a highly visible presence at Oshkosh every year.

Being the largest small piston aircraft salvage company, Wentworth always has a huge supply of avionics and they have their own radio shop to bench test each unit for go/no go. They use the shop to green or yellow tag an item if the owner wishes to pay the fee. Usually, an owner will have his own shop check out the part or unit, a more conservative approach.

Salvage companies are also in a position to buy huge inventories of new surplus items. Duff Aircraft once purchased the entire remaining Beech 18 and Pratt & Whitney inventory from Beechcraft. Duff also specialized in Cessna O-2s, having sold dozens of the retired military version of the Cessna 336/337.

Salvage and the Internet

The Internet has had a huge impact on the salvage industry, especially for buyers. First, its easier for a shopper to find an outlet and perhaps view inventory or at least e-mail a query. Second, an individual can bypass the dealers and view and bid salvage directly. Further, you can buy or sell anything if you find the right spot. We Googled aircraft salvage parts and got 916,000 hits.

The Internet basically allows anyone with the desire and capital to get into the industry. Besides the yards themselves, there are a number of sites that will find a part for you, using their own protocols to search inventories. Indeed, about anything can be found with the right combination of search words and patience.

EBay is one of many sites that does a lot of aircraft parts business and while most of the experiences are positive, when you get taken, you may get taken big. Example: An IO-360-C1C6 was put up for auction. It was advertised as having 1100 hours, but had had a prop strike, and the crankshaft wasnt guaranteed. High bidder was $4700. The high bid was based on the value of the engine, estimated overhaul costs, including a new crank and freight.

When the engine was received, it was strapped to an open pallet, all steel hardware was corroded, and the crank and pistons were rusted tight. The case had a fist-sized hole in it, the sump had been torn from the case and the accessory case was damaged where the sump had been attached. There were no accessories.

With the serial number in hand, the buyer discovered that the engine had been involved in a fatal ground impact. The engine was totally misrepresented, but had definitely had a prop strike and the seller refused to negotiate. The FAA had no recourse and eBay could do nothing. (Where possible, pay with PayPal or a credit card, so you’ll have some recourse.)

Another eBay story involved an Aerostar that was located at a salvage yard. It had been placed on hold with a 10 percent down payment and immediately put on eBay with a reserve higher than the price. When the bid time was over, the successful bidder was asked to pay for the item with certified funds. Before doing this, he wisely ran a title search and discovered that the airplane was actually still the property of the salvage yard, whom he called.

While he was on the phone with the president of the salvage yard, the seller called the yard to arrange payment. The seller was basically making himself a broker without informing the other two parties. He was in a no-lose situation. This story illustrates how buyers and sellers lurk in the shadows on the information highway.

Caveat Emptor

Does the buyer have to be wary when buying aircraft salvage? In general, high-profile companies are conservative to a fault and will err on the safe side rather than shooting for the long dollar. Still, its the salvage business and dealing in high-dollar parts can yield seductively large profits that may tempt some companies to pick, pack and ship without having accurately represented the parts.

Then there are people who get into the business because of the high profit potential and who may be uninformed, naive or simply blinded by the money. These may be honest individuals who simply havent the capital or the expertise to be successful in such a highly esoteric field, either from the buying or the selling end. Its detailed work, categorizing and documenting parts and it requires the same acumen as any other business.

Buying Advice

Be wary of one-man shops or businesses that seem to put all of their resources on their Website. If they don’t get right back to you, go somewhere else. Surely, the best way to protect yourself is to purchase items with a credit card that at least provides some protection against fraud. Large ticket purchases may make this impractical or impossible.

Duff, White and Wentworth all agree that a transaction totally via the Internet is rare. People seem to want more personal contact when buying a part and in the majority of cases, parts are bought by a shop or a mechanic who has a relationship with a particular salesman and likes the opportunity to schmooze. You can tell a lot about a business by talking to its people and we think phone contact is a good idea.

An owner who needs to keep an airplane flying and trusts the FAA inspection process can save a ton of money buying from a salvage yard. We didnt even touch on aircraft models that are no longer manufactured or supported, such as Commanders, Grummans, a number of ag planes, helicopters and so on. If it ever flew, there’s going to be one in a yard somewhere.

We also havent considered homebuilts. Most avionics, instruments, wheels and brakes, engines and propellers for homebuilts come from salvage yards. Terry White told us that his inventory of Continental engines is huge compared to Lycomings, simply because more homebuilts use Lycoming engines. The reason that Wentworth carries truckloads of items to Oshkosh is to service the homebuilt market.

So whether new or classic, certified or Experimental, an airplane will need something at some point and a resourceful, budget-conscious owner will do we’ll to consider salvage parts. don’t let the word “salvage” confuse or sway you. Think of the realistic prices and the availability. Think used, think recycled and think frugal.

Jim Cavanagh is a freelance writer. He owns a Grumman Tiger and lives in Missouri.