The rumors of spring have proven to be founded—which means that the thoughts of pilots are turning to … seaplanes. After winter’s unpleasantness the idea of landing on remote lakes to do a little fishing or dive in for a cooling dip on a hot day causes the prospect of adding on a seaplane rating or—dare we even consider it—buying one of those adventure machines to grow exponentially in the minds of aviators. Visions of SeaReys and float-equipped Huskies dance in their heads until they resolve to quit wishing and take action.

So, it’s time. You’re ready to grab adventure by the throttle and firewall it. But, um, now that you are all the way ready to start flying seaplanes, how do you go about it?

That’s why we’re here. We’re going to go through what’s involved for a pilot who has a single-engine land private certificate or better to add on a single-engine sea rating and what to expect during training. Then we’ll get into how you can make use of the rating, especially if you want to buy a seaplane—selecting the right one for you, finding insurance and taking care of it.

START BY JOINING

The first thing that we recommend for anyone who wants to get into seaplane flying is to join the Seaplane Pilots Association (SPA) (www.seaplanepilotsassociation.org). Membership is $59 per year, which we think is an excellent deal because it provides not just a monthly magazine with extensive technical information, but also state-by-state guidance on seaplane waterway access, a resource library, current list of seaplane training schools, information on seaplane fly-ins and social events as we’ll as advocacy for seaplanes on a local and national level.

GETTING THE RATING

The nuts and bolts of adding a single-engine sea (SES) rating to your current ticket are not even close to overwhelming. For this article we’re going to use a 500-hour, ASEL-rated private pilot as the starting point. Adding on the SES does not involve taking an FAA written/knowledge exam. You go through ground and flight instruction in seaplane operations—more detail on that in a moment—and then take a checkride/practical exam with an FAA Designated Pilot Examiner. That’s an oral and flight test.

Bonus—adding on the rating counts as a flight review, restarting that two-year clock for you.

In our experience, and in talking to seaplane flight schools, a pilot can expect to be able to go through training and the checkride in three days. We’ve seen a few do it in two.

As for resources to help you get ready for training and to pass the checkride, there are a lot available, some free and some for reasonable prices. The book Notes of a Seaplane Instructor, by experienced seaplane pilot Burke Mees, is available through numerous sources—we saw it on the SPA website for $19.95. Sporty’s (www.sportys.com) “So You Want to Fly Seaplanes” video course was filmed at the world-famous Jack Brown Seaplane Base in Florida. We think it’s very we’ll done and worth its $39.99 price.

We think highly of Northwoods Aviation’s (www.northwoodsaviation.com) seaplane training in Cadillac, Michigan. Its website has a free, downloadable Seaplane Training & Operations Manual that is one of the better and more succinct training manuals we’ve read.

PRICES

Our survey of seaplane training schools revealed that prices tended to vary with the type of trainer used—the larger the airframe and/or engine, the more expensive. Many schools offer flat-rate courses with five to seven hours of dual and the checkride. We saw prices starting at $2000 for training in a Piper J-3 and going up from there. The course prices may or may not include the examiner’s fee.

When it comes to selecting the type of airplane to be used for training, we recommend one with a low power-to-weight ratio. That has two benefits: It means less expense for your training and, more importantly, you’ll have to learn finesse on takeoff, something very important for your long-term happiness as a seaplane pilot.

Lower powered seaplanes have to be almost coaxed onto the step during the first part of the takeoff run. Once there, the pilot then has to find the “sweet spot” where the aircraft’s pitch attitude is exactly right for minimum drag so that it can accelerate to liftoff speed.

Training in a seaplane with a high power-to-weight ratio means that the pilot can be a real hamfist and the big engine will still pull the airplane off of the water. That’s great until that pilot loads the airplane up and tries a takeoff on a hot day when finding the right pitch attitude on the step will mean the difference between getting off of a short lake safely or hitting the trees on shore.

Most schools focus on training in floatplanes rather than flying boats such as the Lake Amphibian or ICON A5. While most of the basics of seaplane operation are similar, there are some notable differences between flying boats and floatplanes. That means a pilot trained in one should not try to step into the other without a thorough checkout. If you are planning to do your ongoing flying in a flying boat, go to a school in that sort of seaplane—we note that ICON has dedicated training in its A5s not only for transitioning landplane pilots, but those learning to fly as well.

GETTING READY

Once you select a school it will tell you what you need to do before arrival. At the very least, plan to be current. Not just three takeoffs and landings in the last 90 days, but brushed up on your stick and rudder skills. You are about to do some of the most focused stick-and-rudder flying you’ve ever done. Make sure you have your pilot and medical certificate and logbook and are registered on IACRA—necessary for the checkride.

Your hands-on seaplane training will begin with the preflight where you’ll learn that in addition to doing the sort of airframe inspection that you’ve done for years, you’ll need to spend some time making sure that the floats are in good shape and ready for flight. That means inspecting them, the struts that attach them to the airplane, the wires that keep the floats aligned and the water rudder mechanism. After that, you get to pump out each of the dozen or so compartments that are meant to meant to be watertight, but flexing and twisting during takeoffs and landings mean that water gets in.

LABOR INTENSIVE

If the seaplane is in the water alongside a dock, the preflight may involve either getting it turned around so that you can inspect both sides or calling on your inner gymnast to get across to the far float to finish your inspection. If you are dealing with an amphibious-floated airplane on land, you’re going to need a ladder because the airplane just got four feet taller.

Once in the airplane, in the water, with the engine running, you soon discover that it’s moving all of the time. Every moment. That means planning ahead for everything you want to do, including your runup, and what you want to do is going to be affected by wind, waves, current and other users of the water, notably boats.

Awareness of the wind, its direction and velocity, must become an integral part of your soul when in a seaplane. You’ll learn that it affects everything that you do, even something as seemingly mundane as taxiing for takeoff, because the airplane will seek to weathervane—turn and face directly into the wind—when left to its own devices.

You’ll learn to read the water from on the surface and aloft, and let it tell its story about the wind because it is everything to a seaplane pilot.

Remember that stuff about positioning the ailerons when taxiing that you memorized for the private pilot checkride and promptly forgot? Aileron position is very real when taxiing a seaplane. You’ll also learn the three different types of taxiing—idle, plow and step—and when and why to use them, or not use them.

TAKEOFF

Takeoff is a process. First it’s necessary to get the floats up out of the water so that they plane on it—it’s called getting on the step. That involves holding the stick fully aft and going to full power. Amid the noise and water spray, the nose will pitch up, pause briefly and pitch up a bit farther. Once that happens, you ease the nose down until the airplane is just slightly nose up of level.

The next part of the process is convincing the airplane to accelerate to liftoff speed on the step. In all but the most powerful seaplanes, this involves developing a sensitivity for the behavior of the airplane and a touch to find the pitch attitude for the lowest float drag.

Water drag is a squared function, so as the airplane accelerates on the step, water drag increases dramatically. On a hot, calm day, achieving the last knot or two needed for liftoff can mean a very long takeoff run—and requires all of your skill. Similarly, a downwind takeoff often means that the water drag becomes so high that the airplane cannot reach liftoff speed.

You’ll learn takeoff—and landing—techniques for different water conditions: glassy water, ripples or small waves and rough water.

YAW

In the air you’ll find that the airplane handles much like the landplane version only with diminished yaw stability. Because of the increase in side area of the aircraft forward due to the design of the floats, yaw stability drops. On most seaplanes some sort of vertical fin is added to the rear fuselage or on the horizontal stabilizer to regain some of the reduced yaw stability.

You’re going to be working to keep the ball centered and, of serious import, to touch down on landing without any yaw.

In addition, the floats generate some lift during flight, so the stall speed will drop slightly, which helps in reducing liftoff and touchdown speed.

Landing a seaplane is a combination of the familiar and brand new. You’ll learn to visualize both a runway and traffic pattern where none exist. Approach and flare are much as you’ve done for years, although you may carry a small amount of power through the flare. Touchdown pitch attitude is nose up, but not the nose-high, right-near-the-stall landings you may make in a landplane as you don’t want to drag the aft end of the floats.

Should the water be smooth, or “glassy,” you’ll discover that it is impossible to tell where the surface of the water is when landing. We’re not kidding, a human eye simply can’t. That means learning a technique for minimal descent rate in landing attitude that is held until touchdown—which never occurs when you expect it.

RENTING

You did it. You passed the checkride. It’s time to enjoy seaplane flying! Um, well, there’s an ugly downside to your new rating: There are almost no seaplane schools that will let you rent their seaplanes to fly solo after the checkride. It’s a harsh fact of the insurance market.

However, being a pilot—and successful achiever of goals—bitten hard by the seaplane bug, why not buy one?

There, you said it. You’re ready to acquire a type of airplane that lets you enjoy the sky and the water without changing vehicles.

Then your pragmatic side kicks in: “How do I figure out which seaplane to buy?”

BUYING

That’s why we’re here. Take notes. We talked with Derek DeRuiter, proprietor of Northwoods Aviation, who has been around seaplanes all his life, soloed a seaplane before a landplane and has assisted scores of pilots with seaplane purchases.

His advice started with setting out your reasons for buying a seaplane and how you intend to use it. Is it purely for fun flying? Will you do most of your flying locally—within a hundred miles or so? Do you want to let it take you places we’ll across the map? Do you want to use it for fishing trips? How much weight do you need to carry?

WEIGHT

Derek and other long-time seaplane owners we spoke with told us that weight is a huge deal when you’re flying seaplanes. If it’s a four- or six-place floatplane, figure on only being able to use half of the seats because of the added weight of the floats—even though the float STC will allow an increased gross weight, it is not as much as the weight of the floats. (Many four-place seaplane owners remove the rear seat.) For two-place seaplanes, you can fill the seats, but in most that means having to fly with reduced fuel. Flying boats suffer the same weight issues—you may be able to fill the seats but only carry enough avgas to fly around the block. Look closely at useful load before buying anything.

For fun flying, straight floats work quite well, but they are a real challenge if you want to go cross-country. You will also have to have a way to get the airplane out of the water and secure it soundly between flights, be it parking on a ramp, modified boat hoist or a trailer. If you live where the water becomes solid part of the year, you’ll also need to store the airplane in the off season. For many that means a landing on grass in the fall and launching using a trailer and a high-speed trip down a runway in the spring.

Amphibs make the owner’s life much easier when it comes to getting the airplane out of the water. However, the retractable landing gear adds a big layer of cost, complexity and weight to the ownership equation.

INSURANCE

Before we go any further, we’ll mention that your seaplane selection should be done in concert with your insurance broker as you’re going to be limited in the types of machines in which you can get insurance as a new seaplane pilot. Rule of thumb is that insurance underwriters are terrified of low-time, amateur pilots in high-dollar seaplanes and ones with lots of seats. Start thinking in terms of Cub, Super Cub, older Scout or Husky, Cessna 172 or Piper PA-18. You’ll also need dual in the type, so make sure there’s an instructor around who fits the insurer’s bill.

Insurance is going to be expensive—a friend of ours with we’ll over a thousand hours in type is paying more than $10,000 to insure his Cessna 185 on amphibs.

SELECTION THOUGHTS

To help narrow down your selection, think of power-to-weight ratio. The more quickly you can get off of the water the less pounding the airframe takes.

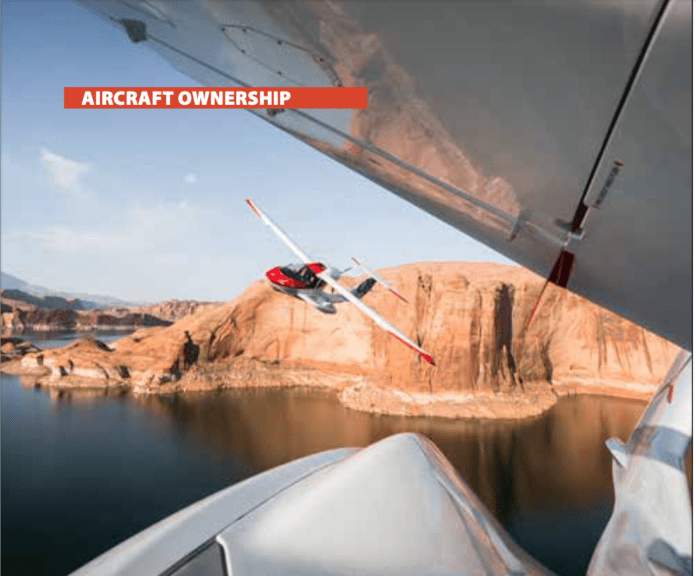

Look at handling characteristics in the air and on the water. We were astonished at the agility of both the SeaRey and ICON A5 on the water, and good manners in flight and on the ground. Floatplanes can be all over the place in the handling category, especially when it comes to the size of floats installed. Many airplanes have options as to float size. Smaller ones are lighter, but float deeper in the water and can be a problem in rough water or high winds.

Stall speed matters. Slower means getting off of the water sooner. We like STOL kits and VGs on seaplanes. If pressed for one or the other, we’d go with VGs because of weight.

Does the airplane have a door on each side? Not being able to get out quickly in either direction can be an issue. Go into that decision with your eyes open.

Wooden spars and/or wing ribs? Stay away, they’re a risk for rot.

PREBUY

We recommend in the strongest possible terms that you never buy an airplane without a prebuy examination. That is especially true for a seaplane for several reasons: It’s regularly subjected to water, so corrosion is of major concern, especially if operated in saltwater; there are no shock absorbers on a seaplane and the floats and airframe take a pounding from even relatively calm water operations, so the airframe and floats must be inspected carefully for damage; if it’s a floatplane, the floats probably cost as much as the airplane, so they must be inspected for condition; and, on amphibs, the landing gear and its numerous cables and pulleys checked.

Make a test flight that includes not only the usual handling checks, but two or three water landings to see how much water accumulates in float or hull compartments.

CARE AND FEEDING

Some years ago we said that the cost of operation of a seaplane is equal to the cost of operating an airplane and a boat, cubed. We have not changed that sentiment. Steve Gruenberg, who has owned the same Cessna 185 on amphibious floats for 32 years, commented to us, “If you want to own a seaplane, just plan on opening your wallet wide regularly.” We concur.

The return, in our opinion, is the ability to make some of the most extraordinary flights possible. We treasure our seaplane flying time.

WHAT WE LIKE

When the spray clears there are quite a few seaplanes that we like a great deal.

For pure fun and some travel in flying boats, the Progressive Aerodyne SeaRey and the ICON A5. For fun on straight floats if modified with a larger engine: Aeronca Champ and Chief; Piper J-3; Taylorcrafts; Cessna 120, 140, 150 and 170; and American Champion Citabrias with flaps.

For fun in the four-place world with modest engines on straight floats (think of the airplanes as two- or three-place in use): Cessna 180, Maules and 180-HP Cessna 172s.

We like the larger engine Lake amphibians, but point out the need for specialized training in the type—it is a fun airplane that can go places.

The top of our list of favorites is the Cessna 185 with the 300-HP IO-550 engine mod and amphibious floats. Next in the line of our favorites, on straight or amphibious floats, are the American Champion Scout, Aviat Husky, Piper Super Cub with either 150 or 180 HP and the 260-HP Maule M7.