Like the Bonanza single, the Beech Baron gets high marks from pilots for its solid and predictable handling, good construction and comfortable cabin. Plus, with its rear cabin door, the Baron 58 series is passenger friendly and easier to load stuff inside compared to the smaller Baron 55 twin.

The other thing the Baron has going for it is supportability. The airplane is still in production today (as the Baron G58) and it won’t be tough to find a shop that can wrench one. But maintenance won’t be cheap and you don’t want to skimp on transition and recurrent training. You’ll also want to get an insurance quote before making a deal on one.

Here’s a fresh look at the used Baron 58 market, where sales pros tell us good 58 models are in demand and refurbished ones bring top dollar.

MODEL HISTORY

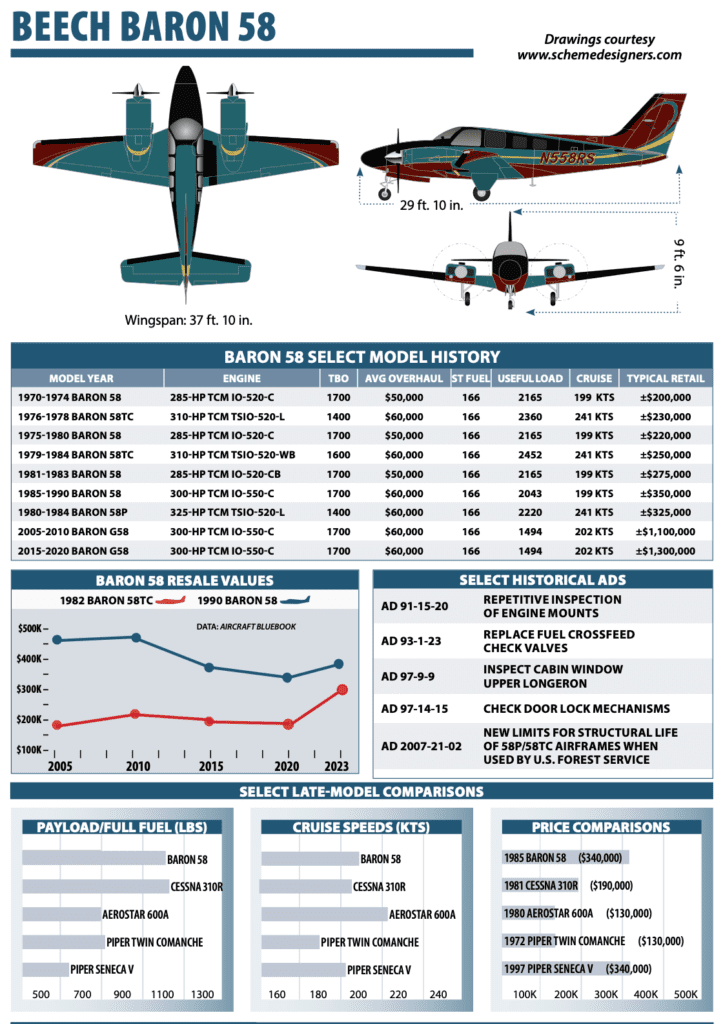

The Model 58 Baron was introduced late in 1969 (as a 1970 model). It shares genes with the Bonanza, making use of essentially the same landing gear and systems, along with a fuselage similar to the six-place 36 series. Its direct ancestry goes back to the 95 Travel Air, which begat the 55 Baron.

The Model 58 had a 10-inch-longer fuselage compared to the smaller “baby Baron” 55 series, and an initial list price of $89,850, just about $6000 more than the shorter E-55 Baron. Average equipped prices were up around $117,000. The extra room in the fuselage did a lot to boost the 58’s utility, and it quickly became one of the all-time favorite Barons. A big, double aft cargo door and three-blade propellers were popular options. The aft doors became standard very quickly, and are the same as those on the 36 Bonanza. The three-blade props became standard around 1972.

Engines on the first 58s were Continental IO-520-Cs of 285 HP each. These engines had the so-called light crankcases, notorious for cracking. Later, the IO-520-CB became standard, but earlier 58s may be fitted with either.

The 58 was such a solid design that few changes were made in the first several years of its production. That’s not surprising, since Beech had worked out the details of the 55 nicely by the time the 58 was introduced. The 58, by the way, is approved as an amendment to the same CAR (or CAM) 3 certificate that covers the 55s. Creating new airplanes out of existing type certificates is something that some manufacturers, notably Piper, developed to a fine art in the 1960s and 1970s.

TURBOS AND PRESSURIZATION

In 1976, Beech introduced two new airplanes based on the 58: the turbocharged 58TC and the pressurized 58P, both with 310-HP Continental TSIO-520-Ls. These engines, too, had light cases, later replaced by the heavy-case LBs. Recommended TBO on the L/LB is 1400 hours. The WB is 1600. The 58’s C/CB now is 1700 hours.

These two airplanes differed from the 58 in more than just equipment. Both were built to FAR 23 standards, and both empty and maximum takeoff weights were significantly higher, with a net gain of useful load in both cases. The most obvious visible difference among the three is that the aft door is on the port, or left, side of the 58P fuselage and is a single door. The now-standard double doors (originally identified as cargo doors) are on the right side of the 58 and 58TC. The interior configuration is the same in all three 58s, except that the center fuselage windows in the 58P can’t open for ventilation on the ground.

In 1979, the TC and P models were upgraded to the TSIO-520-WB rated at 325 horsepower. Maximum takeoff weight was increased from 6100 to 6200 pounds. Pressure differential of the P was slightly increased from 3.7 to 3.9 psi.

The 58TC was discontinued after the 1982 model year, with a total production run of only 151 aircraft. It couldn’t match the popularity of the P Baron, which outsold it nearly three to one. Worth mentioning is that the GA slump caught up to the P Baron in 1986. Still, the normally aspirated 58 kept plugging right along.

A major change happened in the 1984 model year: The 58 got an engine and power upgrade to the Continental IO-550-C rated at 300 HP. Maximum takeoff weight was increased 100 pounds, to 5500.

The panel was also revised, with the new one much better designed, and the cockpit was completely reworked. The center control column, with the throw-over yoke (or large bar for dual control airplanes), was replaced with individual control columns. The big news was that Beech bit the bullet on switch placement: It reconfigured the arrangement of the gear and flap switches to the accepted industry standard of gear selector on the left, flap selector on the right.

Beech had been criticized for adhering to the old backward U.S. Army/airline configuration that was featured on the Beech 18 and all subsequent Beech twins until Dukes and King Airs were reconfigured. In our view, there’s nothing at all wrong with arranging the gear and flap switches that way. However, when the rest of the industry elects to go in the opposite direction, predictable confusion occurs. Just imagine what would happen if, say, Ford decided that the gas pedal should be the one on the left. It was a damned-if-you-do, damned-if-you-don’t situation. Beech twin operators are used to the non-standard arrangement. Introducing similar airplanes with critical controls relocated invites trouble, just as the pilot new to the brand stands in danger of selecting the wrong lever. And, of course, the predictable happened. One of the first new 58P customers, a longtime Baron operator, retracted the landing gear of his spanking-new, very expensive twin shortly after taking delivery. Ouch.

You’ll find that the majority of Baron 58 models are equipped with dual controls. The large control bar obscures many key switches, gauges and controls. Larger pilots find the yoke sits low enough so that legs can interfere with control inputs. This is especially a problem if there are two large people in the cockpit, particularly if the person seated in the right seat is not a pilot. Interference with control input has happened at critical times. The new control arrangement mounts the yoke a bit higher, which helps eliminate the problem for most pilots. It also makes more of the panel visible and accessible.

You can also tell the newer panels by the smaller turbine-type vertically placed engine instruments. This and the rearrangement of many subsystem elements free up a lot of the panel for avionics (nearly 28 percent more available space). Even with radar installed, there is plenty of space for the latest glass displays.

KNOWN ICE AND FUEL

One of the most important changes came late in the 58 series life cycle: known-icing approval, which was not obtained until 1984 or 1985 for the 58 (the 58P was approved earlier). Many Barons are equipped with boots, electric or alcohol props and alcohol windshield anti/deice equipment. Even with placards in the cockpit and notices in the operating manual, many pilots assume that the presence of the equipment equals approval. This is a false assumption that can lead to a host of problems, from physical danger to FAA enforcement action.

Another important variation in configuration to watch for is fuel capacity. Most 58 series have at least 166 gallons usable fuel capacity, although a few normally aspirated 58s have the standard 136-gallon capacity. An increase in optional fuel capacity was introduced in 1976. The addition of wing tip tanks increases usable fuel to 190 gallons.

Pilots flying a mixed fleet of Barons have something else to watch for besides cockpit configuration. Four hours into a flight is rather late to recall that the 58 you are flying today has 136-gallon capacity, not 166 or 190. It is easy to get confused.

PERFORMANCE AND HANDLING

As light twins go, all of the 58s have comparatively good payload with full fuel. A typically equipped older 58, with auxiliary fuel giving a total of 166 gallons usable, can lift 724.5 pounds and fly for approximately 5.5 hours at an intermediate power setting—a still-air range of just over 1000 NM—with IFR reserves.

Newer 58s can carry six people (that’s FAA 170-pounders) and luggage roughly 600 nautical miles with reserves. A typically equipped 58P has a full-fuel payload of just over 700 pounds and a range at roughly 60 percent power of more than 1100 NM at either 15,000 or FL 250 (TAS is 201 at the lower altitude and a smoking 218 at the maximum of FL 250).

All three versions have loading flexibility. The 58TC and 58P are biased toward the forward CG limit. In fact, with many airplanes, full fuel and two people up front (only one in some) can put weight and balance out beyond the front limit. With baggage space in the nose and aft cabin as we’ll as smaller space between the cockpit and middle seats with the club seating arrangement, there are a lot of options for maintaining loading within the allowable CG range.

A 58P owner once told us that the forward CG was so notorious that the Beechcraft pressurized Baron school he attended advised to put a 50-pound bag of sand in the aft baggage compartment. Another said the CG on his 58TC was right at the forward limit with just the front seats occupied and any luggage had to go in the back. This was inconvenient with golf clubs. Some find that in the 58TC the oxygen bottle takes up too much space in the nose baggage bay to fit in golf clubs. We’ve stuffed them (and snowboards) in the nose.

As for handling, who doesn’t like the control characteristics of a Baron? While Barons are generally considered good instrument platforms, and the 58s the best of the group, workload is relatively high because of the responsiveness. They have light control pressures and are highly responsive, but there’s a slight price to pay in turbulence when in IMC, but that’s tamed by a good-working autopilot. Garmin’s GFC 600 (and the integrated GFC 700 in G1000 models) are good performers, while the GFC 600 supports Garmin’s Smart Rudder Bias Vmc roll protection. Many Barons have King KFC200 (or Century) systems and you should look carefully at their performance during a prebuy. Repairs for older systems can be expensive.

When the autopilot isn’t flying, the Baron 58 should be easy to handle for those who are properly trained and who bring their A-game. Comparatively high gear and flap operating speeds help the Baron fit in easily in high-density traffic areas. The basic good handling extends into the lower end of the envelope. Many operators praise the short-field capabilities of the 58. But, beware of the weight and weight distribution differences between the 58 and TC/P and you could find yourself operating out of short fields where careful performance calculations are a must.

For instance, one 58P owner told us that the normal 100-knot approach speed was a problem for him at his 3000-foot strip. After overshooting one landing, he investigated it carefully and he ended up reconfiguring the airplane to put more weight aft, including relocating the battery and installing an air conditioning unit in the tail cone to replace the nacelle-mounted factory design. The changes moved the CG about 4.5 inches aft and it reduced the approach speed to 90 knots. Another pilot told us that 80 knots is a comfortable speed over the fence in a vortex generator-equipped 58, and the airplane still floats a bit at that airspeed (the book says stall in landing configuration is 74 knots; 1.3 times Vso is 96.2, or about 100 indicated). His 58TC at 90 knots was on the margin: “As slow an airspeed that I was at all comfortable with crossing the fence. When you pulled off the power, it landed right now, to the accompaniment of a stall horn and often a buffet.” We highly recommend the installation of VGs on any aircraft they’re available for. See the report in the March 2019 Aviation Consumer.

Overall, we think the 58 is a good-flying airplane throughout its intended speed range. It can handle fairly rough and relatively short strips better than some other twins when properly operated. The relatively fast gear operating speed also reduces the time of maximum exposure (from liftoff to positive climb after retraction).

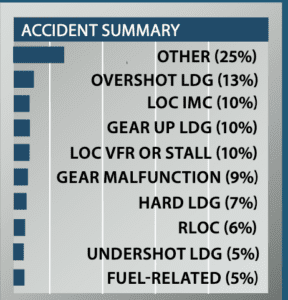

In the process of reviewing the 100 most recent reported Baron 58 series accidents we were struck by the low number of accidents involving engine failures, just three, and the surprisingly high percentage of landing-related crunches, 41. Pilots who experienced engine stoppages seemed to be pretty good at landing safely using the good engine.

Unfortunately, with both engines running, pilots didn’t do as we’ll when it came time to return to the planet. Thirteen landed long and fast enough to go off the end of the runway, five hit short of the runway, one kept going below the MDA until flying into trees, six lost control on rollout (a low number compared to other nosewheel airplanes), seven landed hard enough to cause structural damage and 10 either forgot to extend the landing gear or pulled it up on rollout or on the takeoff roll. One of the overshot landings was the result of a combination of landing long and the pilot pulling the props into feather instead of closing the throttles.

One of the engine-failure accidents involved a pilot who decided to insert himself and six passengers into a six-seat Baron, and initiate a flight with the gear down because it had been “malfunctioning.” Shortly after takeoff a fatigue-cracked cylinder on one engine departed the premises. The flight ended badly.

In the good news department, there were only five fuel-related accidents, none of which involved running the airplane dry. One pilot did not catch that his airplane had been fueled with jet fuel. Another attempted to fly a 58 Baron that had been sitting outside for some time with worn-out fuel caps. The investigation following a double engine failure found a fuel system full of rusty water. One pilot, who was doing everything right enroute, had both engines stop because the fuel valves had recently been misrigged to pull all of the fuel for both engines from a single fuel tank.

There were 10 loss of control in VMC accidents, some of which involved the pilot stalling the airplane. In three of those a CFI was giving dual in a Baron that had a throw-over control wheel. While it is legal under certain circumstances under FAR Part 91.109, those three CFIs were helpless when the left-seat pilot lost control while maneuvering.

There were nine noisy landings due to landing gear that jammed or would only partially extend, a high number. While Barons have a reputation for a tough landing gear, it must be maintained carefully and correctly. All of the accidents were the result of improperly performed maintenance or inspections that did not reveal and replace worn or defective components.

There were three wing explosion events traced to fuel leaks and improper electrical wiring.

Following attendance at an airshow, a 58 Baron pilot with four passengers attempted a roll. He lost control and the airplane broke up inflight.

We felt for the pilot who, after landing, saw a truck and trailer pull onto the runway in front of him. He swerved, but still hit the trailer. The apologetic driver said that he was sure that he could beat the airplane across the runway.

CABIN COMFORT

Visibility is good from all seats. From a passenger standpoint, the middle seats, particularly with club seating, are the most comfortable. The big aft door and separate over-wing door to the cockpit make loading more graceful than many other light twins, plus you sit high in a Baron’s seats, which encourages a good posture and leads to decent comfort on long trips. Plus, modern seating upgrades with good lumbar support help even more. Noise level is about standard for the class: noisy, although it pays to replace the soundproofing in older models.

Other than good ANR headsets, the two best aids for noise and vibration are cruise climb and cruise power settings with lower RPMs and good dynamic balancing of rotating components. Don’t ignore worn engine mounts.

UPKEEP AND MODS

Shop owners will give you a warm welcome when you taxi up in your Baron 58. No, this is not the airplane for tight maintenance budgets. But, with the right preventive upkeep maintenance costs should be about average for a complex normally aspirated twin. That’s not to say that some annual inspections won’t come with impressive invoices.

Beech used to emphasize the fact that the Baron gear (the same as on the former Air Force and Navy T-34 trainers) had been drop-tested to a rate of 600 FPM. However, in the real world of poor directional control/side loads and three-point landings and wheelbarrow takeoffs, the gear and surrounding structure suffer. Knowledgeable operators spend a fair amount on preventive maintenance of the gear system, ensuring that elements are kept clean and properly lubricated in addition to thorough, regular inspection. Before buying one, make sure that the multiple FAA ADs have been kept up with. 97-9-9 called for inspection of the window upper longeron for cracks and missing rivets. 93-1-23 called for replacement of the fuel crossfeed check valves. 92-23-4 mandated modification of the engine control mount supports.

A variety of engine packages are available from Beryl D’Shannon, RAM and Mike Jones Aircraft (previously Colemill) to make the Baron go faster. To help slow it down, Spoilers Inc. offers a spoilers mod. VGs are available from a couple of different manufacturers and we think they serve the Baron well.

For help with training, maintenance, modification and a ton of other useful information, we think any prospective Baron owner should join the American Bonanza Society. Visit them at www.bonanza.org.

At press time, Tennessee-based Mike Jones Aircraft pushed out its first Lock & Key Baron 58 refurb. Using the successful Lock & Key Navajo concept of making the airplane almost as good as new (or even better), the Lock & Key Baron (north of $1.1 million) incorporates most if not all of the Colemill mods that have benefited Barons for years. We’ll look hard at this mod in a separate article in an upcoming issue of Aviation Consumer.

PILOT FEEDBACK

I owned a Baron 58TC for over 15 years, and I studied the normally aspirated 58 before buying it, but the advantages of safety made the 58TC a better choice. Things like a Va of 170 knots instead of 156 knots and a single-engine service ceiling of 14,400 feet instead of about 7000 feet was important when flying in the West (although the single-engine rate of climb was lower because of the much higher gross weight).

Another misunderstood issue is the TSIO-520-LB 310-HP engine versus the 325-HP WB engine from 1979 forward. Performance is virtually identical, except at takeoff where the WB variant could pull another 1.5 inches of manifold pressure. Otherwise, they are identical engines and that 15 extra horses means very little.

The only negative is that Beech made only about 150 TCs and about 470 P Barons. But an even bigger problem is the effective life limit of 10,000 hours on the wing (spar). I bought my TC with 2000 hours and sold it with 3000. But interestingly there is no 500-hour repetitive wing spar AD inspection as in Bonanzas and Barons. The Baron 58 and the P and TC versions fly the same, which is great. I cruised usually in the low teens at 62 percent power, burning around 33 GPH rich of peak (even with GAMIjector fuel injectors I still flew rich of peak) at 168 knots IAS at mid gross weights around 5500 to 5700 pounds).

Another point is the engine nacelles: The P and TC have the engines one foot farther in front of the wing (i.e., longer nacelles), which made space for the turbocharging system. You can easily (with full tanks and two people in front) get out of forward CG. I knew of guys that flew with a 50-pound sandbag in the rear baggage area.

My 58TC was virtually maintenance free. Insurance was expensive, about $5000 per year, and I flew every year in another Baron for two days of training. I wasn’t using mine for training. I’ll save the good story of how my TC came with two brand-new (non hot-rodded) LyCon engines, hoses and baffling.

Larry Weitzman – via email

We bought our Baron 58 a little over three years ago and it has performed admirably during that period. We upgraded from an A36 (which itself was an upgrade from an A35) to accommodate the growing family. The plane is our family hauler, comfortably carrying six people across the country several times a year, along with regional trips for hockey games and such.

As a step-up, the transition was easy. The Bonanza lineage made everything feel familiar from the start. Control feel is very similar, though somewhat heavier, and sight picture, visibility and panel layout are nearly the same. Handling qualities are superb and single-engine traits are benign. I find it easier to fly than the Bonanza. Lightly loaded (say two people and 120 gallons of fuel) she’ll purr along at 130 knots on one engine at 10,000 feet quite contentedly in cooler temps.

Our Baron is a 1985 model, which was the second year of the updated panel arrangement and IO-550 engines. With 600 HP on tap, even at the high field elevation of our home base in New Mexico we typically see 1000 FPM initial climb rates fully loaded (5500 pounds.) At sea level, that rate is closer to 1500 FPM. Our initial legs out of New Mexico are always at 11,000-12,000 feet due to terrain. At our normal 65 percent cruise power that yields a pretty consistent 180-185 knots true. Fuel burn is planned at 25 GPH total, which covers all flight phases. Compared to the Bonanza, total fuel burn averages about 70 percent higher thanks to the speed advantage.

Loading is a non-issue thanks to the nose baggage bin. It’s big enough to hold four carry-on bags, plus the requisite flight kit (oil, tiedowns, tools, etc.). The aft bin can hold two carry-ons and passenger comfort items, and the space between the first two seat rows allows for crew items—plenty of space. The nose locker greatly simplifies weight and balance. Our typical trip loading puts the CG we’ll forward of the aft limit. With 1640 pounds of useful load, we can carry 100 gallons of gas or enough for three hours plus reserves. That works out to a very nice stage length for us.

The Baron is blessed with many of the same simple and reliable systems found in the Bonanzas. Engine stuff is obviously doubled. As an A&P I do most of my own maintenance. Aside from becoming intimately familiar with the plane it helps reduce annual costs. Ours had 1985-vintage avionics when we bought it and we’ve been through a complete panel upgrade over the last two years. That process identified some gremlins that might not otherwise have been discovered, so unplanned maintenance has been higher than expected recently.

Insurance is considerably higher than the Bonanza was, with yearly premiums running about $5000 over the last two years. Despite the higher fuel costs, unexpected maintenance and not having flown as much as usual, I estimate all-in operating costs (fixed and variable) last year was around $300 per hour.

We love our Baron and it fits our mission needs perfectly. It’s a joy to fly and has no nasty handling quirks. It’s faster than the Bonanza, carries more, is more comfortable and with the higher wing loading gives a smoother ride. Take all the best qualities of the Bonanza, stick another engine on it and you get a great plane made even better.

Chris Nichols – via email

You can either go down or slow down, but not both. That was my introduction to the Baron 58. On the outside, it looks like a Bonanza with two engines, but on the way home from Oshkosh shortly after transitioning to the Baron, I found myself at 8000 feet and 15 miles north of my destination airport when Kansas City Center finally cleared me for the visual. As I neared 200 knots in the descent, I pulled the power levers to idle and was quickly reminded the Baron is not a Bonanza.

For initial training, I completed the Baron course at Flight Safety in Wichita, Kansas, several years ago. They thoroughly cover the aircraft and allow you to experience failures an MEI (multi-engine instructor) cannot re-create in the airplane—like an engine failure at 400 feet on takeoff. This type of training is imperative, especially if your flying entails loading the airplane with valued cargo.

As a flight instructor, I am a firm believer in solid training and maintaining currency, especially in a high-performance piston twin like the Baron. I encourage our pilots to be intentional about their currency, and even more intentional about their recurrent training. For the Baron, I advise to find a good MEI that will really help you refine your single-engine approach skills, including dealing with full engine shutdowns and restarts. Bottom line: Make training, currency and continued education a priority with this airplane.

For those who are looking for a great-performing, honest airplane with the added safety margin of an extra engine and that is also comfortable for passengers (and an absolute joy to fly), the Beech Baron 58 is my top pick. As the photo below proves, even my four-year-old agrees!

Jessica Koss – via email