The good news for buyers who can’t afford the eye-popping price of a brand-new Cirrus is the healthy supply of used ones for sale. For as little as $100,000, you might score a first-generation G1 SR22. That’s no chump change, and to be sure, an early SR22 might seem stark compared to the current G5 series. But for an owner stepping up from a Cherokee or Skyhawk, for example, an SR22 will be a major leap ahead in speed, technology and mission capability.

Since Cirrus Design first morphed from a quirky kit supplier to a full-blown aircraft manufacturer in 1998, it has consistently proven that it got the vision thing right. The entry-level SR20 and flagship SR22 in their various iterations have proven hot sellers and good performers, with unusually loyal customers. This seems the perfect setup as the company moves closer to delivering its seven-seat, single-engine Vision SF50 personal jet—a logical step up from an SR22.

What explains the brand loyalty? We think there are several reasons. The airplanes perform we’ll and generally deliver on the claim of being easy to fly for people new to flying. Moreover, they offer the right combination of cutting-edge equipment and construction methods without becoming so radical or quirky that buyers are put off.

The CAPS (Cirrus Airframe Parachute System), which Cirrus pioneered as a signature marketing feature, is a continuing selling factor. In a poll we conducted shortly after the SR22 appeared, we asked if the parachute was a driver in the purchase decision. Only a third of respondents said it was, but we think that understates the case—perhaps even more so in the current market. We suspect the parachute has always been a pot sweetener that pushes buyers considering something else into the Cirrus camp. “The parachute is what sells my spouse on the airplane,” one commenter said.

Cirrus Company History

Among homebuilders, Cirrus was well-known during the 1990s for its VK30 pusher kit, an innovative composite design that gained some traction, but wasn’t a major player in the field. By the mid-1990s, Cirrus principals Alan and Dale Klapmeier developed a new vision, reasoning that the time was right for a high-performance, composite fixed-gear single that anyone could fly.

On a variation of Cessna’s famed “drive it up and drive it down” campaign of the 1970s, the Klapmeiers launched the company on the premise that it didn’t take special DNA to be a pilot. Anyone could do it with the right airplane. And if you got in over your head, you wouldn’t have to die for your mistake; the BRS parachute would pull your fat out of the fire.

The company’s first product was the SR20, which appeared in 1999, powered by a 200-HP Continental IO-360ES. At about $197,000 equipped, the airplane was a good buy and proved a strong seller. It also gave buyers their first look at large-screen panel displays, ARNAV’s ICDS 2000. By modern standards, this would barely rise to the level of rudimentary, but a decade ago, it was pretty slick, even if the display wasn’t as impressive as the Garmin GNS430s that drove it.

Going in, Cirrus knew what Cessna, Piper, Beech and others have always known: If you don’t have a follow-on model, your success will be short-lived.

A New Game

Two years later, for the 2001 model year, Cirrus announced the SR22 step-up model and immediately hit pay dirt. Although the SR20 was no slouch, its 150-ish cruise and limited payload left some buyers wanting.

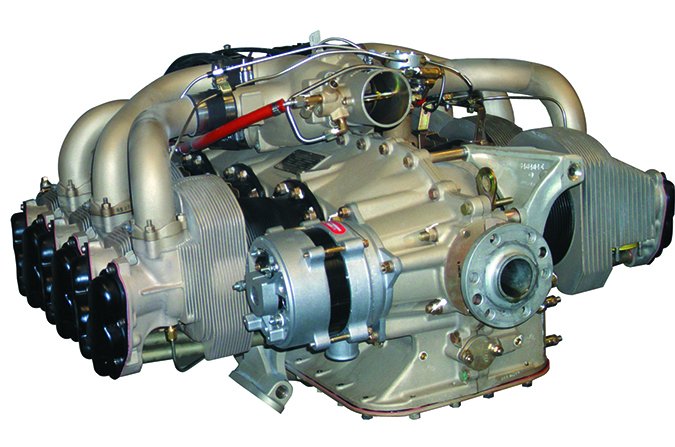

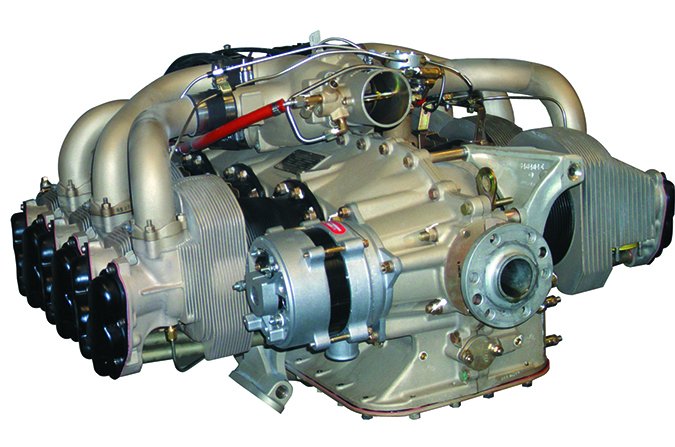

The SR22 scratched that itch. It had a 310-HP Continental IO-500-N, one of Continental’s best-ever powerplants, a three-blade prop and more payload, although the basic airframe is largely the same as the SR20.

The IO-550-N brought some improvement to the front end. It’s a bit more economical and doesn’t have the altitude-compensating fuel pump that can be a maintenance nuisance in the SR20s.

Cirrus pioneered the two-lever control, so the SR22 has a throttle and mixture lever, but no prop control. The RPM is handled by a cable-and-cam arrangement that sets the RPM at either 2700 RPM for takeoff or 2500 RPM for cruise. Most owners seem to like this arrangement, but for those accustomed to three levers, it takes some getting used to. We’ve learned to love its simplicity.

The SR22 airframe is slightly different than the SR20. The wingtips are 18 inches longer, the rear elevator is larger and the landing gear was moved inboard to give more ground clearance for the prop. Although identical in section to the SR20, the SR22’s main spar is substantially beefed up and accommodates more fuel, 81 gallons in the SR22 (92 in later ones) compared to 60 gallons in the SR20. The SR22’s energy-absorbing seats were modified to account for the airplane’s higher weight.

Speaking of weight, the SR22’s gross is obviously higher and so is its payload—increased further with the current G5 model. When we flew one of the first factory demos in 2001, the aircraft had an 1152-pound useful load or 648 pounds with full fuel on a 3400-pound gross. When the SR22 appeared, Cirrus had just certified a 100-pound upgrade for the SR20, giving it a 3000-pound gross weight with a useful load of about 1030. On equivalent fuel, the SR22 enjoys a 120-pound advantage. We’re told by most owners, however, that the SR22 is typically flown with one or two people aboard, full fuel and all the baggage you want.

The SR22 will blister along at 170 to 180 knots on about 18 GPH rich of peak. But not many owners run the airplanes that way, given the reality of avgas prices. Throttling back to 65 percent on the lean side gives about 15 GPH and 172 knots. You can easily push that up to 80 percent power on 17 GPH and recover some of the lost speed. This appears to be where most owners operate the SR22. The IO-550 is smooth and perfectly happy in this regime. It will run even leaner for max-range cruise.

The 17 GPH setting yields about four hours of endurance for a still-air range of 700 miles, with reserves. At the max range setting, 1000 miles is doable, as we’ve proven.

SR22 Construction, Systems

Along with Diamond, Cirrus pioneered high-volume composite construction for light aircraft. When this technology was on the horizon, the aviation press was allowed to believe it would be stronger, lighter and cheaper than metal, even if Cirrus didn’t exactly say that. Well, it did say stronger and the Cirrus airframe demonstrably meets this claim, according to static structural tests. Cirrus did full-scale crash testing of prototype fuselages at NASA’s Langley, Virginia, facility that revealed that even at high impact loads, the composite fuselages remain relatively intact.

The fuselages are laid up in molds in two halves, with the two shells joined and then cured in an autoclave. The wings are similarly constructed and are of a single piece built around and bonded to a massive spar. This forms a strong torsion box that has proven we’ll in the rigors of real-world service. But unlike Cessnas and Diamonds, de-winging is a challenge, given the single-piece structure. Control surfaces are conventional riveted aluminum, with a combination of push-pull tubes, cables and bellcranks and a sidestick controller rather than a yoke or center stick. Most of the control circuitry lives under the floorboards, where it’s accessible via generous inspection panels.

As with the SR20, trim is entirely electric via a single coolie hat on the side controller—fore and aft for pitch, side-to-side for aileron. Some early SR22s also had electric rudder trim, but that was later deemed unnecessary. Because the pitch trim motor is aggressive, mastering smooth pitch trim changes requires a deft touch to avoid bobbles. We wouldn’t mind a slower-turning servo motor or even manual trim with an old-fashioned wheel. But that goes against the grain these days.

That’s also true of the SR22’s nosegear and main gear system. It has a castering nosewheel and steering is via differential braking, the weight-saving design philosophy that every major manufacturer seems to follow these days. This works we’ll enough in the real world, but has the downside of chewing up brake pads and, in the case of the SR22, leading to several brake-induced fires. This led to an AD requiring periodic O-ring replacement and a brake temperature inspection hole. Some owners say brake wear isn’t an issue if you stay off the binders during taxi. As for the castering nosewheel, it makes the airplane a dream to taxi into a parking spot, but a nightmare to hand-push into a hangar.

The wing section and planform is uniquely composed of varying sections, thus the leading edge has the characteristic split on the outer panels. Because the outer panels have a lower angle of incidence, they remain flying while the inner sections have stalled, improving control through the stall and theoretically adding spin resistance. The Cirrus aircraft aren’t approved for spins and in place of proving spin recovery, the BRS parachute is provided as the equivalent level of safety.

The fuel system in the SR22 consists of wet cells in each wing. These are plumbed to a single tank switch located on a console between the two pilot seats, which is in plain view and situated near the fuel level gauges. Owners of G1 and G2 models complain of inaccurate fuel gauges, and while there was an aftermarket digital fuel sender and control head upgrade offered by CIES, it had problems, too.

While the fuel is relatively well-protected in the wings, it appears to be not as well-protected as in other aircraft, specifically the Diamond line. Our review of accidents reveals a higher incidence of post-crash fire in the SR22 than in Diamonds.

In keeping with its new-age approach to safety, Cirrus ridded its models of vacuum instrument systems as soon as it could. Although the very early SR20s had vacuum pumps and later became all-electric, SR22s were all-electric right out of the blocks. It has two alternators and two batteries, each electrically isolated from the other and either capable of powering essential electrics. The main alternator is 60 amps, the secondary is 20 amps while the main or starting battery is 10 amp hours. The secondary is composed of two smaller 12-volt batteries connected in series.

As do transport aircraft, the SR22 has more than a single electric bus; two in fact, a main and an essential that, in the event of a battery/alternator failure, will power sufficient avionics to continue the flight. Either can power the essential bus.

On the downside, both alternators are gear driven, one on the front of the engine and one on the rear accessory case. Given the service history of Continental alternators, our druther is to have one belt driven. In any case, we think the all-electric airplane is a significant advance over anything to do with vacuum instruments, which owners have tolerated for years because there was no choice, but that’s changing.

The two models share the same CAPS ballistic parachute but with its 3400-pound gross weight, the SR22 can be up to 500 pounds heavier. That means descent under canopy could be as high as 28 feet per second compared to the 24 feet per second typical for the SR20. That’s a vertical descent of 1680 FPM/19 MPH versus 1440 FPM/16 MPH. Cirrus has said it and we’ll say it again: A ride to touchdown under the CAPS canopy won’t be something you’ll want to repeat, although the vast majority of real-world deployments have yielded no or minor injuries.

Models and Maintenance

Buying a used SR22 is not like buying an older Cessna 182 or a Saratoga. That’s mainly because you won’t see much post-factory equipment variation on Cirrus aircraft. They emerged from the factory fully formed and the panels don’t allow many options to mix and match. Some of the early steam gauge airplanes are getting Aspen Evolutions, Garmin G500s or were converted to Avidyne glass.

The original SR22s had an “A” and “B” option list. The A airplanes, which retailed for $276,600, had a Garmin GNS430/420 combination, an S-TEC System 30 autopilot and a Century NSD-1000 electric HSI. The B airplanes ($294,700 retail) had dual GNS430s, a System 55 autopilot and a Sandel color HSI. Both options had the ARNAV ICDS-2000 color MFD. The only other option in the early airplanes was a Stormscope and, later, the Goodrich Skywatch system. At the time, we liked the panel but predicted the ICDS-2000 wouldn’t be long for the airplane.

We were right. Within a year the ICDS-2000 was replaced by the Avidyne FlightMax MFD and most of the early aircraft have been converted. By the 2003 model year, SR22s with Avidyne’s Entegra PFD/MFD glass cockpits found their way into customer hands. The Avidyne airplanes had GNS430s, a System 55 autopilot and Avidyne’s E-max engine monitoring. TKS was available as an option in the earliest SR22s, but it wasn’t approved for known icing. That option didn’t appear until 2009.

In the 2004 model year, the SR22-G2 emerged, which featured a redesigned cowl, a new prop, a spiffed-up interior, an improved door latch design and a six-point engine mount that addressed vibration issues in the first SR22s. It’s a huge improvement.

Early on, Cirrus discovered something unique about its buyers: A substantial number of them would replace a recent model SR22 if a newer model had noticeable improvements. We know of many Cirrus owners who have bought two or three new airplanes in the space of five years or less—even in a softening economy.

Not one to let this opportunity pass by, Cirrus rolled out one of its best sellers ever in the form of the turbonormalized SR22 for the 2007 model year. Cirrus had heard its customers ask for a turbocharged SR22 and Dale Klapmeier once told us the company had considered it from early on. Unfortunately, Cirrus couldn’t get its in-house developed turbo to run cool enough, so it never brought the product to market.

To address the demand, it did something unusual: It contracted with Tornado Alley Turbo to install a turbonormalized system under STC. These airplanes proved so popular that for a time, they outsold the normally aspirated version by a margin of two to one. Many owners traded up to the turbo model.

Some of them traded up again a year later when Cirrus announced the G3 model with several improvements, including a redesigned wing with 92 gallons fuel capacity and a carbon fiber spar, the removal of the aileron-rudder interconnect found on earlier models and improved environmental and interior ergos.

Hot on the G3’s trail the next year was the Perspective model, a version with the Garmin G1000 EFIS suite adapted specifically to the Cirrus. It has synthetic vision, a flight director and the GFC700 autopilot with a unique save-my-bacon button that, when pushed, automatically returned the aircraft to wings-level flight.

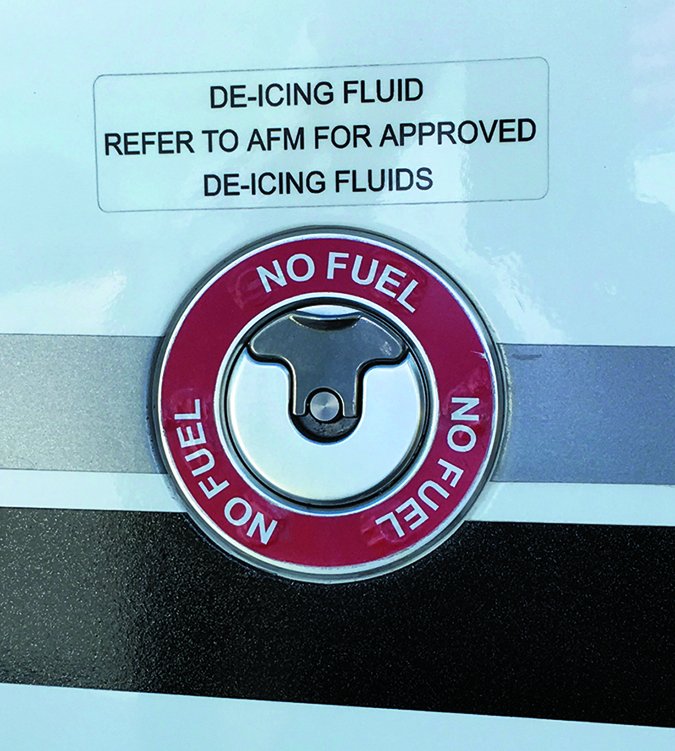

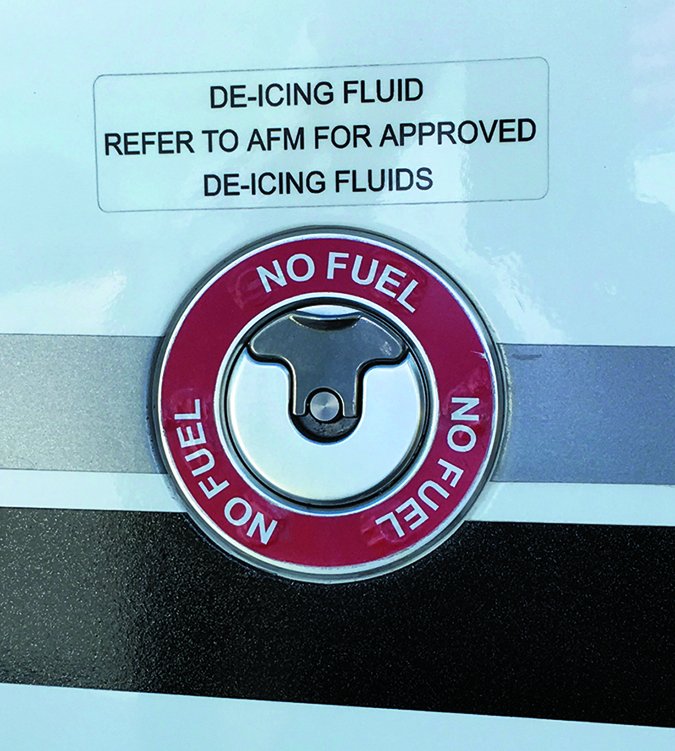

Even as aircraft sales hit the skids in 2008 and 2009, Cirrus continued to introduce improvements to the SR22. In 2009, it began offering a known-icing package based on the TKS system that had always been available as an uncertified option. In 2010, it finally got its in-house turbo installation sorted out and introduced the 315-HP TSIO-550-K-powered SR22T, to sell alongside the turbonormalized model, which remains in the lineup today.

0)]

The latest version is the SR22 G5, introduced in 2013. The G5 brought a variety of improvements, including optional tri-color paint work, a new 3600-pound gross weight, plus a welcomed 50-percent initial flap extension speed of 150 knots, up from 119 knots on older SR22s. With an additional 3.5 degrees of extension, this makes the aircraft much easier to slow on descent. To accommodate the new gross weight increase, Cirrus beefed up the main spar, strengthened the landing gear and added extra layers of composites to the airframe.

Speaking of composites, when composite airframes hit the market, one selling point was that they wouldn’t corrode, parts wouldn’t break and they would be cheaper to maintain. This might have proved somewhat true, but whatever savings were lurking in the statistical noise got chewed up in higher avionics costs and, especially, database costs.

It’s not that the avionics in the SR22 break more often than other aircraft, but there’s more of them and owners report that once off warranty, flat repairs run into big dollars. Recurrent database and datalink weather subscription costs are also something owners of a decade ago didn’t spend as much on. You get more with these systems, but you pay more to keep them up, too.

On the plus side, the IO-550 has proven to be a durable and economical engine. We’re not seeing many complaints about soft cylinders or premature failures. We don’t see a widespread pattern of the engines not making TBO—if treated right.

A scan of the FAA’s Service Difficulty Reports revealed some complaints. Door fit and inadvertent opening is a problem in the early models. Cirrus addressed this with a redesign of the latch. Front wheel shimmy can be a problem. In one case, the wheel pant departed the airplane. A few other SDRs dealt with nosegear wear issues. There were also a handful of alternator and starter drive adapter failures. These are common in Continental engines and not unique to the Cirrus.

The SR22 has a total of 14 airworthiness directives, a fair to middling score. None of these are especially onerous or expensive, but some do impact safety, such as 2008-14-13 which requires door hinge replacement to prevent the door from departing the airplane, 2008-06-28 which addresses significant PFD issues and 2007-14-03, which requires a modification of the CAPS activation system.

And speaking of CAPS, the earliest airplanes are we’ll at the point of needing the 10-year repack/recertification. How much? Plan on about $13,000 all in, if you go with an overhauled unit, but close to $15,000 for a new one. G1 aircraft require costly composite repair and paint work following a repack, but the CAPS is accessed through the baggage area in G2 models and beyond, eliminating the need to break the structure to gain access.

Speaking of paint work, if the paint is showing its age and you’re tempted to upgrade to a more modern scheme that mimics a new Cirrus, you could get into a copyright infringement issue, since Cirrus has copyrighted its modern schemes.Scheme Designer’s Craig Barnett—who has dealt with the issue firsthand—told us it’s best to check with Cirrus before spraying.

Cirrus Market Scan

Because of the habit of buyers upgrading with each new model, Cirrus has been a victim of its own success. This became especially obvious in the fall of 2008 and spring of 2009 when a flood of SR22s of various vintages came on the market. At one point, we estimated as many as 200 might have been on the block.

As we reported in the December 2015 issue of Aviation Consumer, Cirrus eventually divested itself of owning any used inventory, partnering with Ohio-based Lone Mountain Aircraft Sales and TAS Aircraft Sales in Portland, Oregon, to carry, manage and resell the used inventory. A used Cirrus with a factory-certified pre-owned status carries a six-month, 100-flight-hour limited factory-backed warranty. But you don’t always have to pay the certified preowned premium (roughly 10 percent, on average) to get a decent used Cirrus.

We think the best buys are the 2002 to 2004 aircraft with Avidyne avionics—particularly an early G2 model. The Bluebook lists these for we’ll under $200,000 retail and we don’t doubt bargains are out there. The 2001 to 2003 SR22s are even cheaper, with retail prices as low as $100,000. These likely won’t be all-glass models—many have steam gauges with an Avidyne MFD. The interiors on these first-generation SR22s were never a high point and many of these older models have tired seats and carpets.

1)]

The Cirrus airplanes are exceptionally well-supported in our view, both by the factory and by one of the best owners groups around, the Cirrus Owners and Pilots Association at www.cirruspilots.org. For a detailed look at real-world performance numbers on Cirrus aircraft, see www.cirrusreports.com.

SR22 Crashes: Landings, IFR OPs

Our survey of the most recent SR22 accidents led us to question a long-held opinion about handling on landing and wonder why Cirrus pilots seem to have so much trouble hand-flying their airplanes in IMC.

In the years we’ve flown the Cirrus SR22 line, we’ve felt that they were pretty much middle-of-the-road airplanes when it came to level of skill required to make a landing. We flew them on-speed on approach in varying levels of crosswind and found that control authority and responsiveness were predictable and comparable to other airplanes in their class.

After noting that 39 of the SR22 accidents involved landings, we’re beginning to wonder if the airplanes are less than forgiving of pilots who won’t fly at the recommended approach speed. Only 16 pilots lost control on the runway, about average for a nosewheel airplane, but 10 didn’t have things collected we’ll enough to land, went around and crashed during the go-around; three landed so hard they damaged the airplane; three hit something on final approach; and a surprising eight undershot their landings, hitting short of the runway. We have heard reports of high sink rates if a pilot lets the airplane get slow, and find the NTSB reports give supporting evidence.

Our recommendation after looking at the landing-related accidents for the SR22 is to fly at the speed recommended in the POH, not any more, not any less.

2)]

We did note that almost all of the RLOC accidents involved gusting crosswinds. Given what we also saw regarding issues with Cirrus pilots hand-flying their airplanes in IMC, we are concerned that the level of automation has caused correspondingly unsafe levels of complacency in Cirrus pilots and a loss of stick-and-rudder flying skills.

Fully 10 percent of Cirrus accidents involved loss of control in IMC—another two were the result of continued VFR into IMC. For an airplane that can compensate for pilot foolishness or impairment, we were surprised at these numbers. One Cirrus pilot took sleeping pills in a suicide attempt. After he passed out and a tank ran dry, the autopilot set up a controlled descent and the airplane landed.

Because many SR22s carry some form of flight data recorder, we are getting more insight into the dynamics of IMC loss of control accidents and learning that the automation is thus far not a silver bullet for increasing the level of safety. It may be working in opposition as pilots over-rely on it or get confused by its complexity and misprogram it.

A notable accident involved a pilot who engaged the autopilot five seconds after liftoff in anticipation of climbing into IMC. He misprogrammed the autopilot. Over the next four minutes, he fiddled with it rather than fly the airplane as he made several turns and stalled the airplane twice before crashing.

On the good side of the equation, we note that there were at least 15 successful CAPS deployments, saving a number of lives. A few of those were after loss of control in IMC.

SR22 Owner Feedback

My military, airline and accident investigation background affected my purchase of a 2013 SR22 G5. When I started researching my first aircraft purchase, I spent nine months focusing on the Beech Bonanza. A FedEx pilot advised me that living in the wintry Northeast made a Cirrus with TKS and the G1000 Perspective worth considering. I fly an MD11 with a glass cockpit and HUD, so when I saw the avionics and autopilot package in the SR22, I was sold.

When I next watched athlete Ken Griffey Jr.’s video about him enjoying his Cirrus, I knew that if he could fit in it, so could I. My first demo ride with Eric Sanderman, the Cirrus New York territory sales rep, confirmed the spacious and comfortable cabin I hoped for. After Eric corrected my habit of flaring high from my job flying the MD11, it was a done deal.

With my Navy and FedEx flying experience, I entered general aviation flying expecting a high level of standardization with recurrent training and found that Cirrus pilots are getting more of it.

3)]

Cirrus Standardized Instructor Pilots (CSIPs) are another step in the right direction for Cirrus pilots. Cirrus itself controls the initial training and annual renewal of CSIPs, ensuring the program’s quality. Insurance companies recognize the CSIP value and usually require owners to undergo factory/CSIP initial and may reward for CSIP recurrent training.

I call the Cirrus a “mini MD11 on steroids.” My Cirrus affords me a similar high level of situational awareness that I’m used to in the MD11, plus the advantages of satellite weather and synthetic vision. After I soon retire from FedEx, I won’t have a great copilot to keep me honest. However, the Perspective avionics with electronic data subscription allows me to not deal with paper, since my backup ForeFlight charts are on my iPad. This is great for single pilot ops.

I have the composite prop upgrade, which enhances both takeoff and landing performance on my 2900-foot home runway. I also had Lancaster Avionics in Pennsylvania install the upgraded Garmin Perspective software with ESP (enhanced stability protection), plus user defined holding patterns.

I’ve accumulated 450 flight hours and the airplane is more than midway through a five year spinner-to-tail Cirrus warranty. Other than new main tires and adding an Air Wolf oil separator, my periodic oil changes and annual costs are reasonable, with all work done by Jim Markey at Private Flight at Sullivan County airport in New York. My first two annuals were pretty clean and came in just over the expected labor costs.

My annual insurance rate for a $700,000 hull value with $2 million smooth coverage is just over $6000, with a 10-percent premium return for each claim-free year. A rough calculation of all costs since new (excluding training) has been about $165 per flight hour.

John Gabriel

via email

We purchased our normally aspirated 2006 GTX G2 in 2009 to use in support of our Connecticut-based aircraft insurance business, coming out of a Mooney 252. We were looking to get into an airplane that was simpler and less expensive to maintain than our turbocharged Mooney. Most of our trips are 100-300 miles, with several Florida trips each year. Our typical annuals run between $4500 and $6000. We had sizable annuals the last two years, including an engine overhaul, airbag seat belts and repacking the CAPS (nearly $16,000). I recommend finding a shop with lots of Cirrus experience.

We did the factory IFR transition with a local CSIP and were skeptical that it would take 15 hours to complete the transition, but it did. Our lowest-time (and youngest) pilot got through the course the quickest. It took me about 18 hours, and I found the training materials thorough.

Our airplane has the Avidyne MFD/PFD driven by dual Garmin GNS430s. If you have not flown with a large PFD/MFD combo, you are in for a treat. The setup works really we’ll and takes a lot of the work out of cross-country trips. Having the big weather picture and being able to instantly look at METARs along your entire route is a great improvement over calling Flight Service and straining to hear them on a VOR frequency. Get used to using speed and altitude tape bugs—it makes flying the airplane much easier, especially the altitude bug. I wish you could view the entire CMax approach plate, rather than having to scroll from view to view, but I think it is way better than paper charts. The geo-referenced airport chart with the airplane’s position superimposed takes the sweat out of getting around large airports, even at night.

We typically run between 65 and 70 percent power, and see between 165 and 170 knots true at 7000 feet, which is where the airplane seems happiest here on the East Coast. Fuel burns (lean of peak) are around 13.5 GPH with stock fuel injector nozzles. We are considering adding GAMIjectors next year to get the temperatures a little closer together, but the engine runs quite happily we’ll lean of peak.

After flying in the Mooney, the Cirrus cabin is ludicrously spacious and comfortable. Even a tall person in the back seat will not feel cramped. The positioning of the sidesticks frees up the space where the yoke usually is and gives you a great view of the panel. We didn’t really notice any difference between using them and a conventional yoke after the first five minutes of transition.

Our airplane has the S-Tec 55X autopilot and we really like it. It is fully coupled, will fly rate-climbs and descents and has GPS steering for full route intercept and tracking. Like other owners, we notice the autopilot’s tendency to Dutch roll when flying an ILS approach, but overall it works we’ll and is easy to use.

My least favorite thing about the SR-22 is the trim. There is no fine-tuning and no manual wheel, so getting trim exactly right, well, you just don’t always. We’ve heard all kinds of solutions. Most commonly, pilots turn on the autopilot and let it trim the airplane. Hand-flying straight and level requires the use of the altitude bug and an active instrument scan, even on a perfect VFR day. Stick forces are heavy, but there is plenty of control effectiveness. There is also plenty of rudder/aileron interconnect. During takeoff you need full right rudder and a fair amount of right aileron, which can startle you the first time you rotate.

4)]

Most pilots won’t have much fun or get much utility from the airplane unless they have an instrument rating and remain fairly current. Flying in the system took me a little while to figure out. Since flap speed for the first notch is a slow 119 knots, you really need to get the airplane slowed up early. The gear is already down and there are no speedbrakes. The only thing you have to slow you down is pointing it uphill and the propeller. If you let this airplane get too far in front of you, it will take a while to catch up to it.

Our G2 has two alternators, but only the primary will run everything. If you lose it, you need to land soon. The second alternator is quite small and stretches your battery’s glide a little bit. We have the older non-known-ice TKS system, and it will give you protection for about 25 minutes, but there is no fluid gauge. It really is meant to get you out of ice—not a system to take it on.

If you are considering an SR22, make sure that you measure your hangar first. Wingspan is almost 40 feet. Ours has about 6 inches of clearance on either side. Pushing it in with the castering nosewheel is not for the faint of heart. Get a tug.

Cirrus got the SR22 mostly right. I wish there was an elevator trim wheel, more deice fluid, two full-size alternators, speedbrakes and higher flap speed. But it flies at a reasonably fast speed, has good range and payload and is extremely comfortable. It is nice to know the CAPS is there. There are enough used ones out there that the older ones are pretty well-priced for what they offer. All in all, we are very happy with our G2.